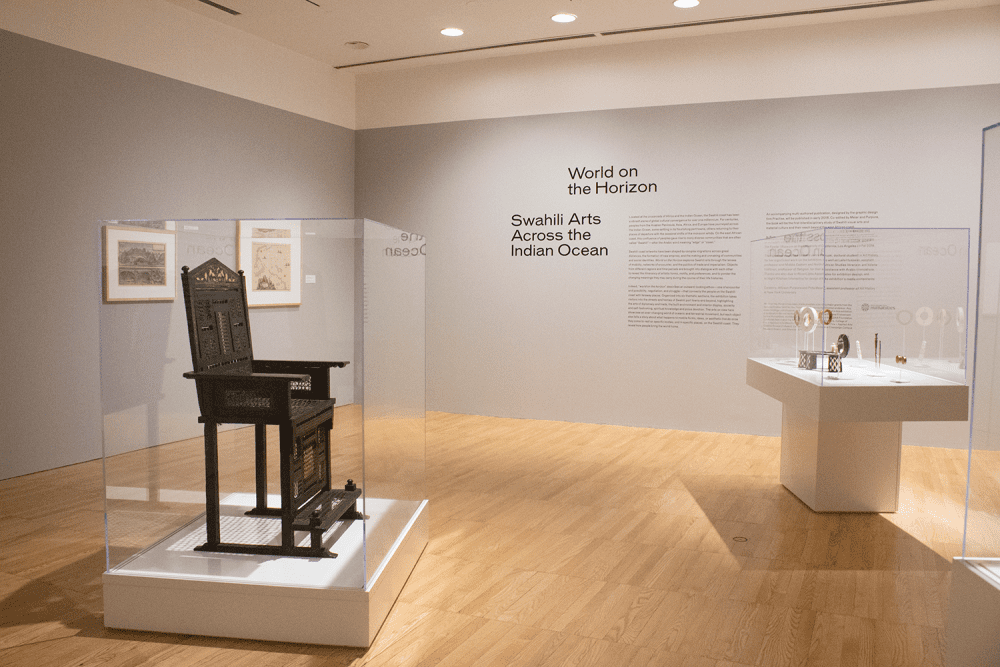

World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean opened at the Krannert Art Museum (KAM), University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in August 2017, and was recently on view at the National Museum of African Art (NMAfA) at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Co-organized by Prita Meier, now associate professor of art history at New York University, and Allyson Purpura, senior curator and curator of global African art at KAM, the exhibition examines the Swahili coast as a space of encounter articulated through multifaceted, migratory objects. Six thematic sections take visitors into the streets and homes of Swahili port towns, investigating the arts of diplomacy and trade, the built environment and domestic interiors, society and fashion, and spiritual knowledge and pious devotion. A related catalogue (published by KAM and Kinkead Pavilion, 2018) includes twenty articles by a range of European, American, and African scholars. The exhibition will be presented in its final venue at the Fowler Museum at the University of California, Los Angeles from October 21, 2018–February 10, 2019.

Elizabeth Rodini visited World on the Horizon at NMAfA, then spoke to Purpura about the conceptual structure of the exhibition, its engagement with geographical essentialism and the politics of place, as well as the complexities of presenting an exhibition about mobility and transformation in a static gallery space. What follows is an edited transcript of Rodini and Purpura’s conversation, conducted via Skype in July 2018.

Elizabeth Rodini: Let’s begin at the beginning: did you and Prita start with key objects and arrive at the theme of the exhibition, or did the theme drive the selection of objects? How did those elements speak to one another? I ask because different sorts of institutions have different working methods, and I’m sure preparation was a long process.

Allyson Purpura: It was a very long process. The theme definitely came before the objects, because Prita and I had been doing research independently on the coast for many years. We both loved the idea of doing an exhibition about the Swahili coast as an intersectional, interstitial region connecting the Indian Ocean and the African interior. When Prita came on board at the University of Illinois, we already knew each other’s work and we thought, we really have to do this. It was like spontaneous combustion.

So we started thinking about what kinds of objects could possibly tell these very complicated stories of confluence and mobility. The paradox, really, lies in presenting such stories with inert objects in fixed vitrines within galleries that are also contained. That’s often the challenge for curators working with concepts of mobility and fluidity.

And there are so many different kinds of stories that are embedded in these objects: sociohistorical stories, stories about Swahili cultural life, but also stories about globalism, empire, and the coming together of visual motifs and aesthetic sensibilities—the objects themselves instantiate the fluid relations and intersectionality of the coast.

So the question became: which objects could tell the stories of movement and transculturation that we wanted to tell, and how could we open those stories up? And the other way round: what do these objects want to tell us? How do we show that the arts of the Swahili coast are very much “of the coast” and yet global at the same time? How we read the objects, the cues we take, depends of course on our own philosophical, political ways of thinking about the Swahili coast.

Rodini: Your point about fixity and unfixity is important. What are some curatorial devices you thought would be effective in helping unfix static objects and challenge the stasis of geography?

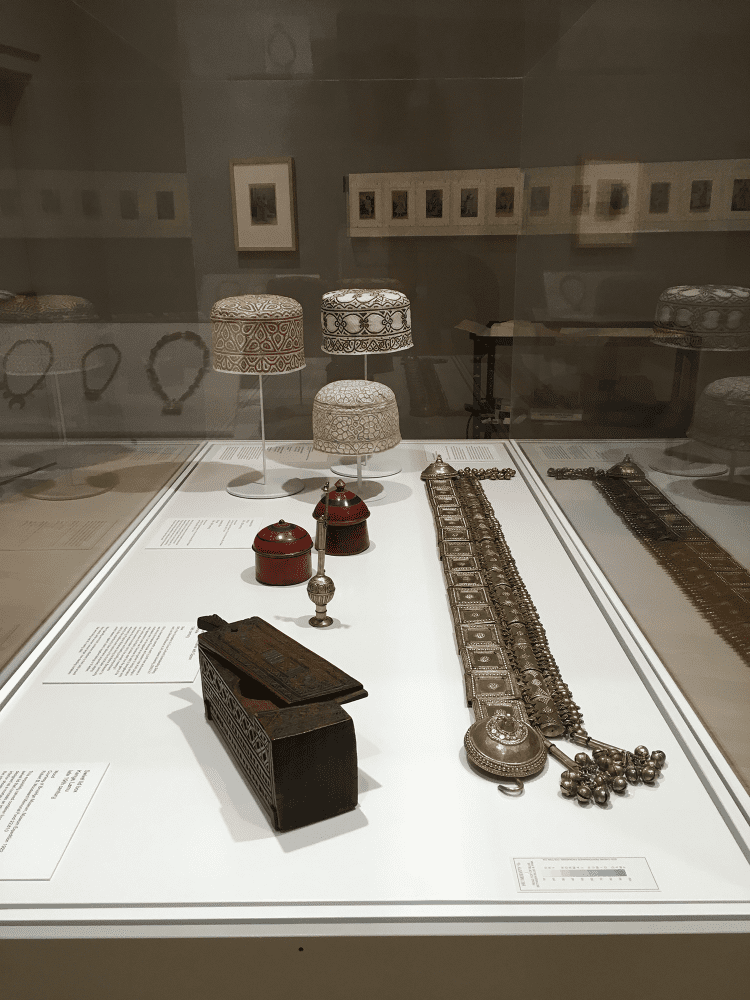

Purpura: Three strategies come to mind. The first, and most important, is object adjacency. We tried to take objects from different geographical regions and different time periods and place them in conversation with each other. Of course the text helps to link them, but visually, kinship between the objects was key. That kinship opens up the critical capacity of the object; the relationality between objects is where the stories emerge. That’s where we begin to be able to push against the stasis and fixity of exhibitions—by trying to listen to the tension or the dialogue those objects are having through adjacency.

Rodini: Is there an example you’d point to of a particularly successful grouping of objects, one that did exactly what you wanted?

Purpura: One case of objects that was visually powerful held mid-twentieth-century Makonde masks from Mozambique, and ivory Kongo and Kuba oliphants from central Africa made in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. The masks tell the story of the representation of outsiders in the Makonde world view, revealing the cosmopolitan perspectives of artists who were themselves migrating between Tanzania and Mozambique and also being exposed to the worldliness of the coast. They are carved wood—wonderful spherical forms that create a lively visual tension with the gorgeous horizontal and vertical sweeps of the ivory oliphants. The oliphants convey histories of the sovereignty and independence of central African kingdoms, but one of them was also a presentation piece, likely commissioned by a European from an African artist.

So these clusters created a story about connectivity and mobility in eastern and central Africa in ways that were quite distinct and yet that had strong connections with each other. The ivory oliphants also open up stories of the slave trade; and like nearly all east Africans historically, Makonde people were affected by the slave trade, but also reconstituted themselves.

Rodini: I found that point particularly fascinating, about populations that were reformed through these mobilities as well.

Purpura: The larger story is one of resilience and reconstitution, but also of the devastating and brutal effects of slavery, told through the themes of movement, encounter, and self-awareness. These are also very “reflexive” objects in that they were produced with viewers in mind. In a sense, they refer to or mediate relationships: to an audience, an interlocutor, and also the histories in which they were embedded.

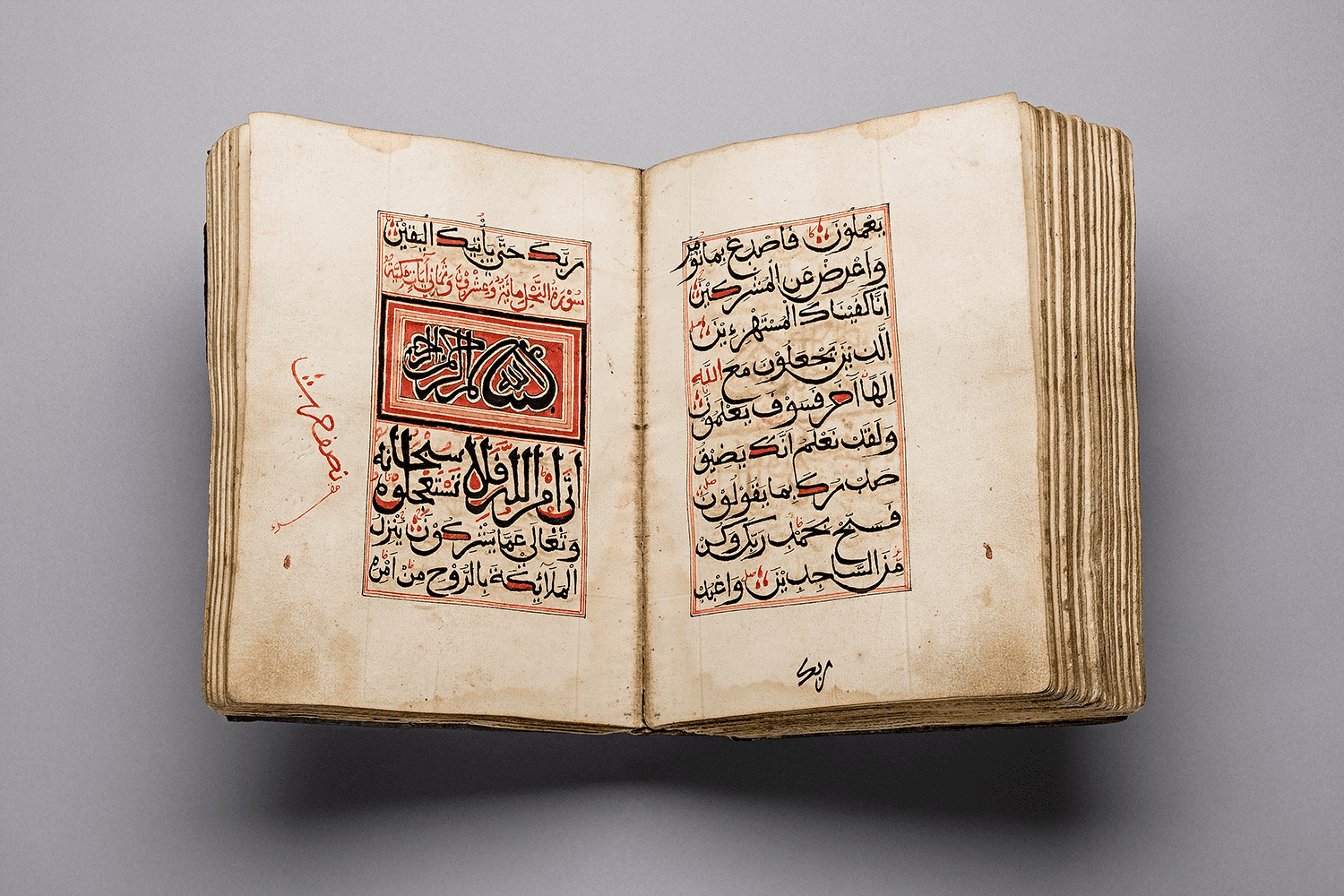

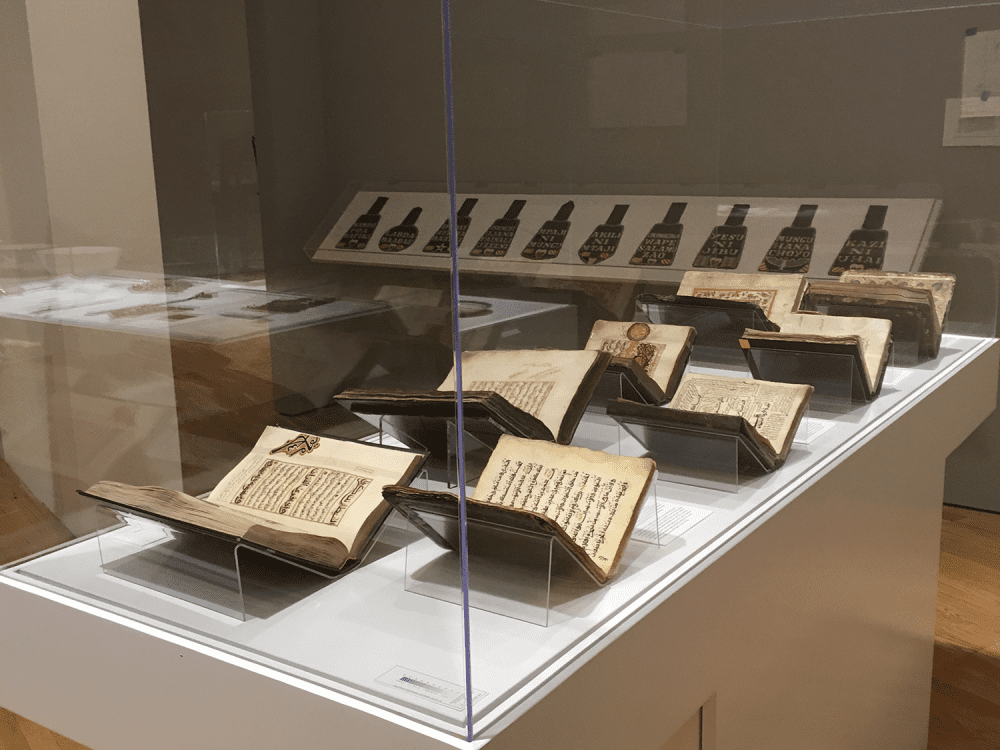

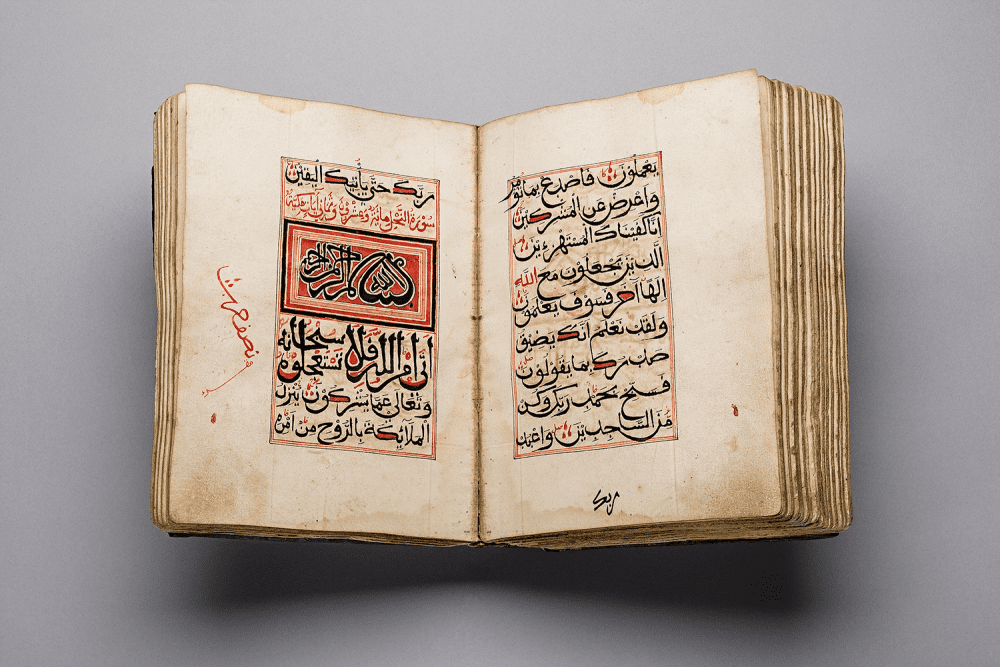

Another compelling adjacency was in the “Presence of Words” section of the exhibition. A case of illuminated Swahili Qur’ans was installed at a right angle to a case of bicycle mud flaps from Zanzibar, which was decorated with Swahili sayings. The flaps demonstrated the pleasure Swahili coast residents take in language and its visual form. While the written word, as the word of God, is highly ornamented in the Qur’ans, words themselves are the agent of ornamentation on these playful mud flaps.

Rodini: It’s interesting to consider “adjacency” as a lived concept as well. The context of your exhibition is the Swahili coast, it’s all about proximity and interconnectivity, and yet this coast today also has very clear political definitions and, I’m sure, many fraught international and internal relationships. So I wondered if that ever became an issue with your African collaborators and lenders—along the lines of, say, we’d prefer you talk about this as “Kenyan” as opposed to “Swahili.” Is that something that you had to confront as you were working with these objects?

Purpura: That’s a great question, and it happened in a different sort of way. The project is really about an arena, a whole region, from central Africa to India and beyond, largely during the age of empire. But it is also a story of interaction and exchange as seen through the location and lens of the Swahili coast, a place that is itself interstitial—that brings all these people and things together, yet is a place in itself too.

Thinking about the globality of Africa tends to be dominated, at least in this hemisphere, by a transatlantic orientation: Africa is seen as global toward the West. But of course Africa is global to the East and South as well. While most of our Kenyan colleagues were Swahili, from the coast, others were not. Yet all were very excited to use Swahili arts as Kenyan arts, to help broaden the story of African globality and Kenya’s contributions to it.

Such confluence and globality is not just a Swahili story. It’s the whole of Africa. Central Africa, for instance, is a kind of ocean in itself. People like to talk about “the” Luba, Kuba, Tabwa, and the Lega—but these people were moving and shaking for thousands of years before they became siloed into distinct categories, which are themselves artifacts of colonial-era anthropological and art-historical epistemologies. You know, territories were always shifting, chieftaincies rising and falling, cultural histories blurring and merging.

But to get back to your question: though it’s really context-specific, some political tensions linger between coastal and inland residents that stem from conflicts over rights to land, political power, citizenship, and resources that can be traced back to the slave trade and to ethnic, racial, class, and labor politics under the sultanate and colonialism. These intersecting histories produced situations in which Swahili coast residents with family connections to the Middle East, for instance, were seen as “foreigners,” interlopers, as not “native” to the coast, while at one point in Zanzibar’s history, it was labor migrants from the mainland, and their descendants, who were seen as foreigners. From such politics emerged contestations of belonging and entitlements, controversy over property rights, the movement of global capital and investments being controlled by one group over another, and the like.

So, maybe ironically, objects embodying histories of cultural movement and mixing can get caught up in these intraregional politics as well.

Rodini: Can you tell me more about how that played out in your exhibition?

Purpura: Well, we were hoping to borrow two Swahili siwas, magnificent, monumental side-blown horns, one brass and one ivory, from the NMK. Like the oliphants from central Africa we talked about earlier, these late eighteenth-century siwas are vital symbols of northern Swahili sovereignty and identity, and are imbued as well with spiritual power. The ivory siwa is on view in Nairobi and the brass one is in Lamu, on the Swahili coast. Our loan request was turned down as their importance as iconic objects of Kenyan cultural heritage was just too great to allow them to travel. Also, the ivory horn was already the subject of discussion between Nairobi and Lamu—it has been on view at the NMK in Nairobi for decades, but the elders of Lamu have asked to bring the siwa back to the Lamu museum, to the vicinity of its origin. And so when we came along asking to borrow it for our North American exhibition, well, that just was not the right thing to do! And then there’s the ivory issue—the strict laws governing even antique ivory’s transport, its implication in the violent decimation of elephant populations—that’s a key part of the story that necessarily prevented this loan from going through.

Rodini: That’s fascinating—the stories of what does not make it into an exhibition can be as revealing of social and political configurations as the exhibition itself. Once you had a firm sense of what you would and would not be able to include, how did you go about organizing an installation that could communicate these various complexities?

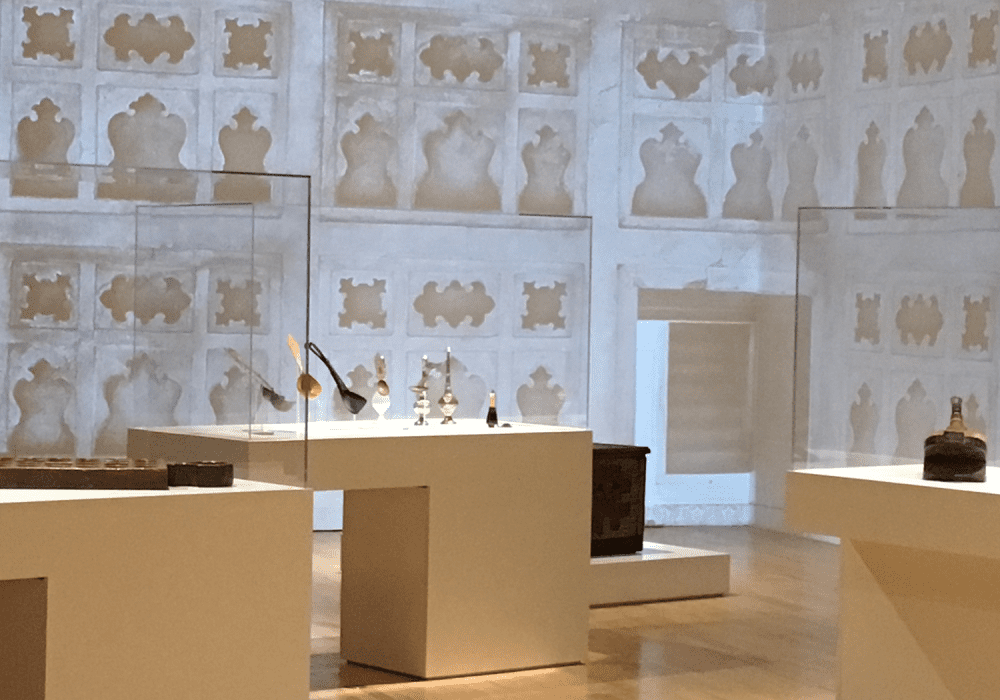

Purpura: Design of the gallery space was critical. At KAM, we worked with Rice+Lipka Associates, an architectural design firm based in New York City. They created a restrained, very elegant installation that gestured toward the monumentality of the striking coral rag architecture of Swahili port towns. Following cues from images Prita and I provided them of Lamu and Zanzibar towns, Rice+Lipka designed a layout that was both open and intimate, with sight lines across the galleries that created fortuitous adjacencies and connections across themes; they also painted the galleries in light gray and white tones that suggested the geometric play of light and shadow that animates the old town alleyways.

Rodini: So object adjacency was one strategy for unfixing these objects and their geographies, but you mentioned that there were two others.

Purpura: Another is how we thought about the text. We knew how complicated these stories were, and we had relatively long labels—at a university museum, we have a bit more leeway there than other sorts of museums do! We used a three-tiered approach—thematic section texts, “gang” labels, and individual object labels1—which nests layers of explication within those three levels. But that’s pretty standard practice.

Rodini: One detail that struck me as unusual in your labels was your attention to where objects were collected, in addition to where they were likely produced. Is that typical with these sorts of materials as a way of identifying them, or is it something you included to make another sort of point?

Purpura: It was the best way forward because of the nature of the object histories. We’ve lost nearly all the original collecting information; and we don’t typically have records of artists’ origin, or of where objects were actually fabricated.

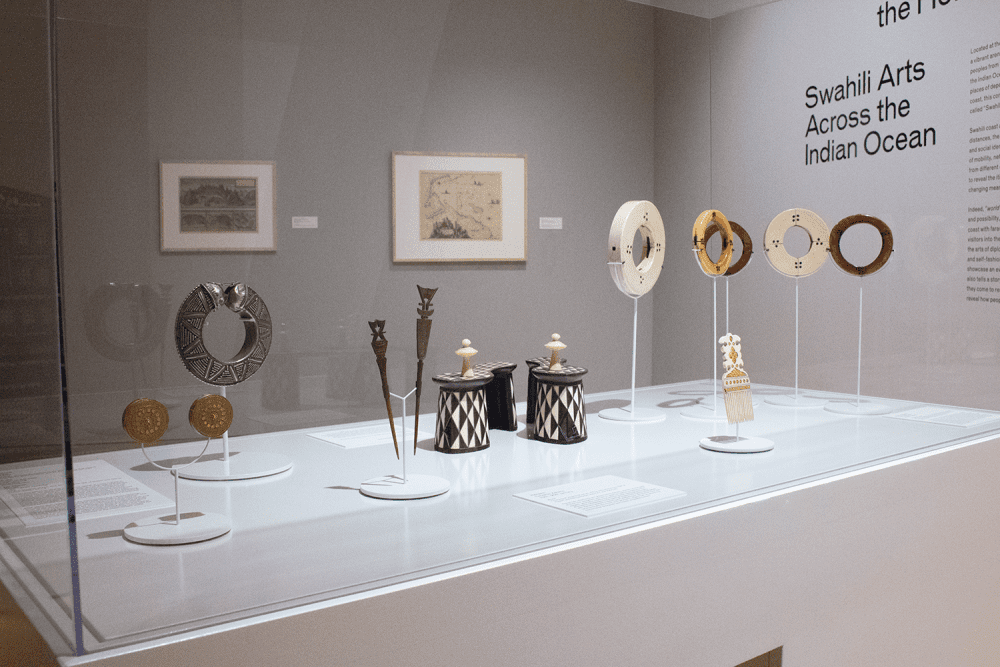

Take the introductory case in the KAM presentation, which was one of our favorites. It had, among other objects, a large silver bangle collected in Zanzibar, and two gold ear spools also collected in Zanzibar—but where were these actually made? Of course an object has an origin, it was made some place, but these objects—or their designs—were highly mobile. It becomes a story of the multiple origins and intersecting trajectories of any one object. I may have a hunch that that bangle was made in Yemen because of its design, but there are lots of these bangles found in Zanzibar, too. Perhaps they were brought there by Yemeni women as part of their family heirlooms; or maybe they were fabricated in Zanzibar by local silversmiths. That’s what we’re talking about when we talk about confluence.

Rodini: And was this the problem that prompted you to do the video piece that was at the opening of the exhibition?

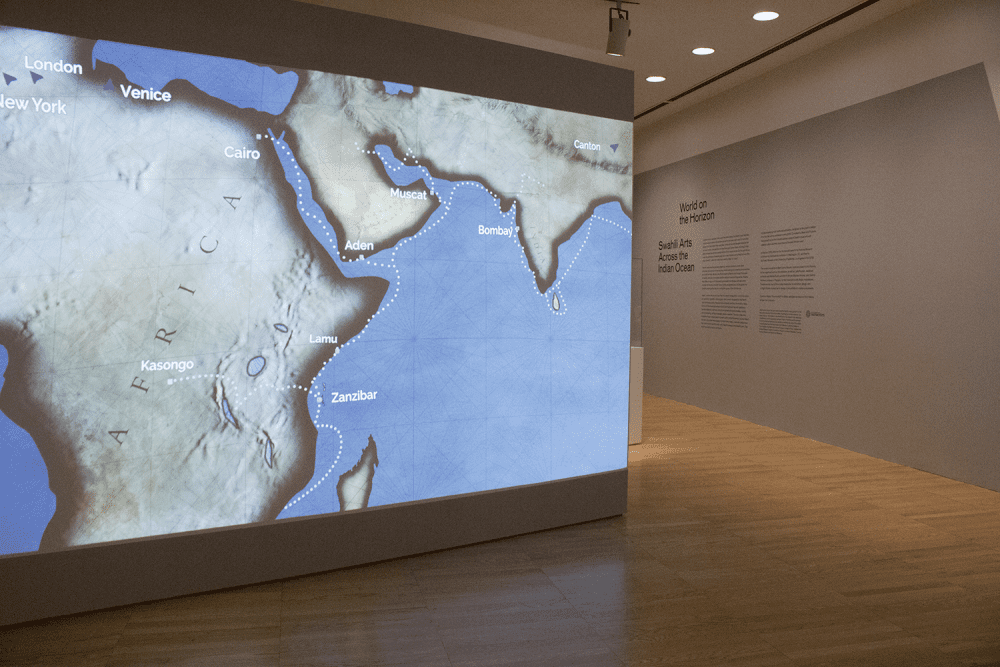

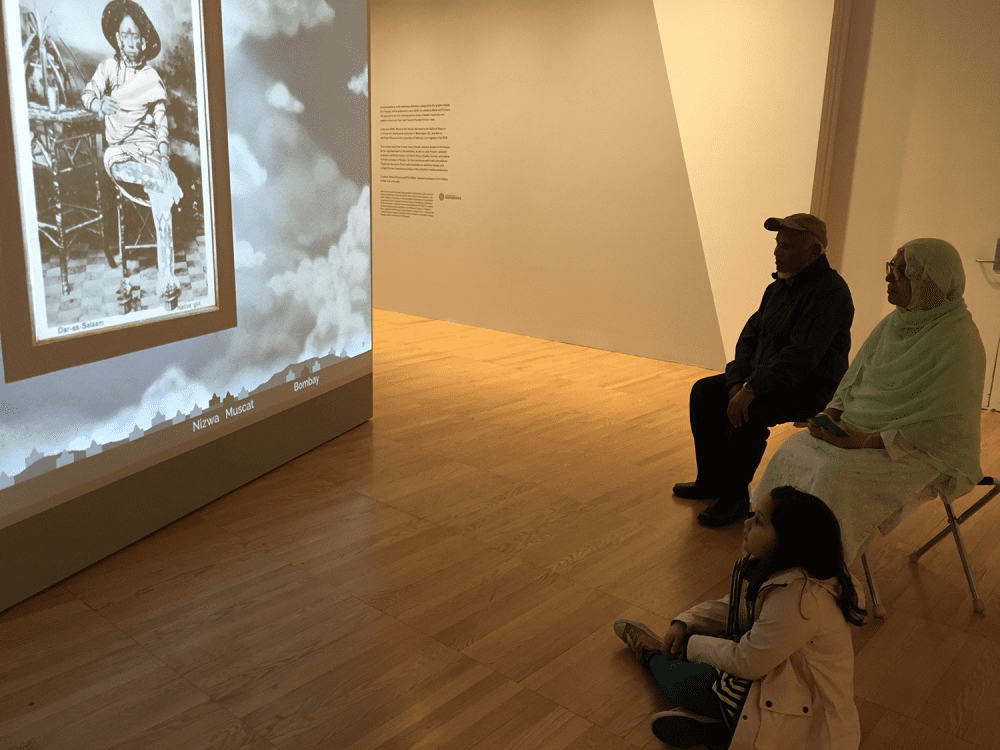

Purpura: Yes, that’s it exactly. The video, produced by the design firm Night Kitchen Interactive, was a third strategy for telling stories of mobility within the space of an exhibition. We didn’t want to be too didactic about this. Our original idea was to have a large, immersive room that would convey connectivity and movement in an impressionistic, atmospheric kind of space.

What we ended up doing, though, was more filmic, more narrative than atmospheric. At KAM the video was shown on a twelve-by-eight-foot wall by a—magical!—short-throw projector. So it was the first thing you encountered when you walked into the gallery, this huge wall, boom. Just right at you, twelve feet of the Indian Ocean. We really wanted movement, we wanted it to be even vertiginous—

Rodini: You’re on the boat, it’s rocking back and forth . . .

Purpura: Yes. And then of course the soundscape—the creaking of the dhow and a little bit of ocean and then the bustling sound of the streets . . .

The challenge Prita and I put to Matthew Fisher and Valentina Feldman at Night Kitchen was: how do we visualize this vast geographic reach, the movement and multiplicity and connectivity, all this stuff going on at the same time? And there’s the history, too. How do we convey the temporal and spatial stories simultaneously? Night Kitchen came up with the idea of doing what they called object “explorations.”

They created a “geo-legend” on the bottom of the screen, and different parts of the selected objects illuminated in sync with different places around the Indian Ocean, Africa, and Europe. This hinted at how the form or ornamentation of any one object had multiple possible cultural influences; it also conveyed a sense of itinerancy.

Rodini: I thought that was very effective. When I went into the show and I was looking at the ceremonial chair from Zanzibar, for example, I found myself searching for that history of assemblage and layering. I was looking at the object differently.

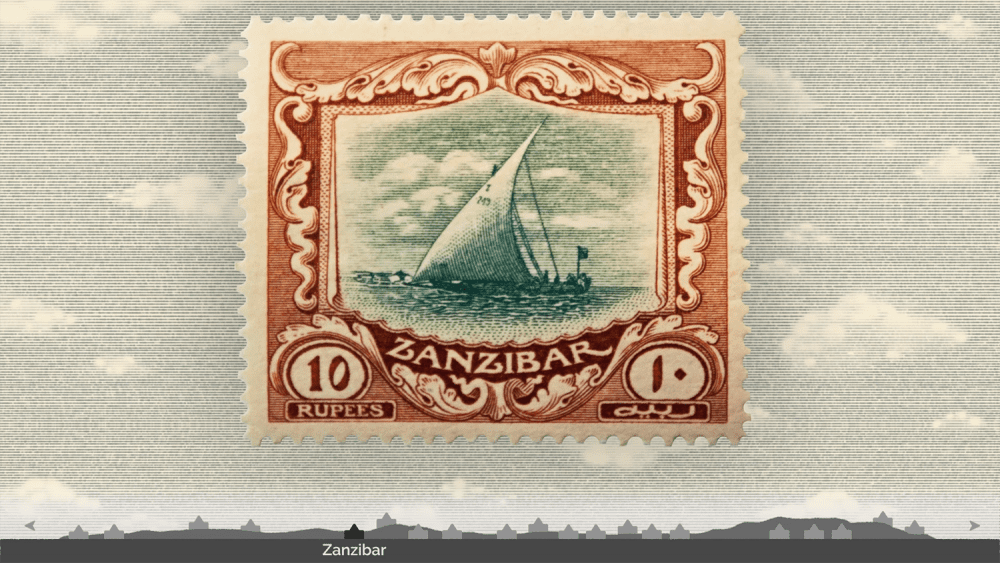

Purpura: That’s great. That was the intention, that people also connect objects from the video with the exhibition. Except the stamp, which wasn’t in the show.

Rodini: I liked starting with the stamp though. It made such a strong point, because we all know what a stamp is for, that a stamp is intended to be mobile and make mobility possible.

Purpura: Yes, exactly! That’s one of my favorite parts, that the video starts with the stamp and the stamp becomes the dhow sailing into the Zanzibar harbor.

Rodini: And those transformations in the video also speak, metaphorically, to the fluidity of objects that is at the core of your thesis. I appreciated how the video activates that theme for the viewer, but also how it creates a fuller context for the objects, a sense of geography and of place—so that these objects feel both mobile and located, in circulation but not unmoored.

That context is important because most people in the United States, including me, don’t know much at all about this part of the world. Or the ideas we have about it are so oversimplified, and so often negative—Mogadishu equals war and terror and destruction, for example. At the same time, there must be intense, internal struggles over what these places mean, about who’s who and how everyone fits into local history. As a curator, you have to somehow simultaneously address people who know next to nothing about Africa and this complicated African constituency, or try to explain this region both as a whole and as fragments.

Purpura: Yes, that’s so well said, and true. And that’s why I, at least, had to keep reminding myself: it’s an exhibition, it can’t do everything. Again, the biggest challenge for an exhibition like this is, which stories can you tell? How do you prioritize? You don’t want to force words into an object. And yet, curating is, after all, an interpretive practice. And how we see these objects is informed by our own study and understanding of these local and intersecting coastal histories. There’s just so much that you can do—and how complicated you can get before you begin to lose people, or move too far afield from the objects themselves?

Rodini: But if someone who associates Mogadishu primarily with war leaves associating it with other ideas, that would be a success, without having to be didactic.

Purpura: Yes, that would be a success. When I bring visitors through the KAM galleries, where we have contemporary works by African artists on view in a variety of mediums, they’re often surprised: “So Africans paint canvases? They do contemporary art?” These realizations, as basic as they may be, are little triumphs. Maybe it’s not even so little. Like you said: they make art in Mogadishu instead of—

Rodini: Terror?

Purpura: Yes, instead of being seen predominantly, thanks to the media, as warlords. That’s the real and lasting efficacy of an exhibition, to be able to offer alternative perspectives.

Rodini: It’s about how we see the other, if we see the other. You know, we’re living in a moment where cultural borrowing is a highly suspect activity. There’s a lot of negative language around it, as “appropriation.” But your presentation of the Swahili coast, where fluidity seems the defining way of being, made me think about what is gained from cultural borrowing. I wonder if there are things we can learn about living in complex, multicultural societies from looking at an exhibition like yours. Maybe that’s a lot to put on an exhibition’s shoulders, but it’s something I thought about moving through it.

Purpura: That’s one of the most interesting things I’ve heard about what you can take away from this exhibition—thinking about what can be learned from these transcultural places where people are borrowing all the time. But what really is cultural “borrowing”? And is it always intentional? The differences between appropriation, borrowing, repurposing are that they can imply different relations of power—who has the right to borrow from whom, who loses, who is injured, or benefits from that act. Those, I think, are the important questions to consider.

Purpura: Two of our catalogue authors, Paola Ivanov and Jeffery Fleisher, explore theories of mimesis as a strategy for forging long distance affinities and alliances. For Paola, for instance, it is a process of consciously creating aesthetic and performative resemblances to those with whom you want to be affiliated.2 Unlike appropriation or repurposing, mimesis is a way of mirroring others to create mutual recognition and a sharing of values.

This gets us to our contemporary moment, in which difference is, increasingly, seen as a threat. As I implied earlier, I’d like to think that the show could provoke some critical thinking about the profound xenophobia and nativist, nationalist resurgence generated by Trump and Brexit and—

Rodini: —nationalists all over the world.

Purpura: Yes.

Rodini: I may be idealizing the power of an exhibition, but this is definitely a case for having the exhibition on the National Mall. Not that you could get the current resident of the White House to walk down and look at it. But I happened to see it on one of the days of the Smithsonian’s annual Folklife Festival, dedicated to Armenia and Catalonia, two places with their own challenges of identity politics and conflict. It was also blazing hot. So I thought, some people are going to dive into the NMAfA for the air conditioning and may see it and even connect it with something larger or something they already know. The potential audience, and the context of the Mall as the nation’s stage—that’s important.

Purpura: Yes, that would be terrific—and one of the many reasons why we were so excited the exhibition travelled to NMAfA. Along similar lines, we haven’t yet talked about Islam. It was such a huge topic that we chose not to treat it as a separate subject in itself; but by not doing so, it actually got treated almost in the best way it could be—as an equal part of everything else. There are lots of different ways that we explore Islamic practices and identities through the objects—Qur’ans and amulets are the most obvious—so Islam feels completely contextualized as an indigenous part of Swahili culture.

People like to talk about “Islam on the periphery,” and some question whether Islam is indigenous to Africa. But how long do you have to be someplace to be considered indigenous? Where does indigeneity begin and end? It gets back to the politics of origins, and to essentializing constructions of what is “foreign” or “native,” which the show aimed to unsettle.

Rodini: The way you describe your treatment of Islam reminds me of how you were thinking about the origins of objects. You can’t always locate or fix it; it’s part of the network of life. And there’s a play between the larger, worldwide community of Islam, the umma, and local practices as well.

Purpura: Yes, but one thing we do not want to convey to audiences is that the specificities of place don’t matter. Beyond my work in Zanzibar, I’ve taken direction from the work of anthropologist Aisha Khan, who writes on critical race theory, religion, and the east Indian diaspora in Trinidad. At the risk of oversimplifying, her article “Journey to the Center of the Earth: The Caribbean as Master Symbol” cautions us not to lose sight of the concrete—the local conditions and communal relations playing out on the ground that are often occluded by celebratory ideologies (and theories) of “creolization.”3 And as we say in our introductory wall text—this was Prita’s turn of phrase—we’re interested in how objects “come to rest on specific bodies, and in specific places, on the Swahili coast.”

Rodini: As someone who works on cross-cultural exchange in the early modern Mediterranean and is interested in the challenges of displaying these fluid histories in museums, I wanted to ask you how the lessons learned from your show can be applied beyond it. Because although the Swahili coast might be particularly inflected with exchange, every place is inflected with exchange.

Purpura: I think this show, with its focus on blurring categories and traversing borders, encourages us to focus not only on the mobility of objects, but on the social and aesthetic values they accrue over time, and on what those journeys and accruals can tell us about the politics of difference and networks of affinity in culturally confluent places like the Swahili coast. So I’d say one of the main takeaways or applications of the show is to promote a relational, itinerant view of aesthetics that can help us explore the broader questions of when and why we draw boundaries between peoples and cultures. This line of inquiry might even offer museums a way forward by revealing buried, silenced, or unexpected connections and conversations among the artworks in their collections.

Rodini: That brings us back our opening discussion of your three main curatorial strategies, which might be generalized to all sorts of times and places. So one last question to conclude: is there anything that you would do differently if you were to do the exhibition again?

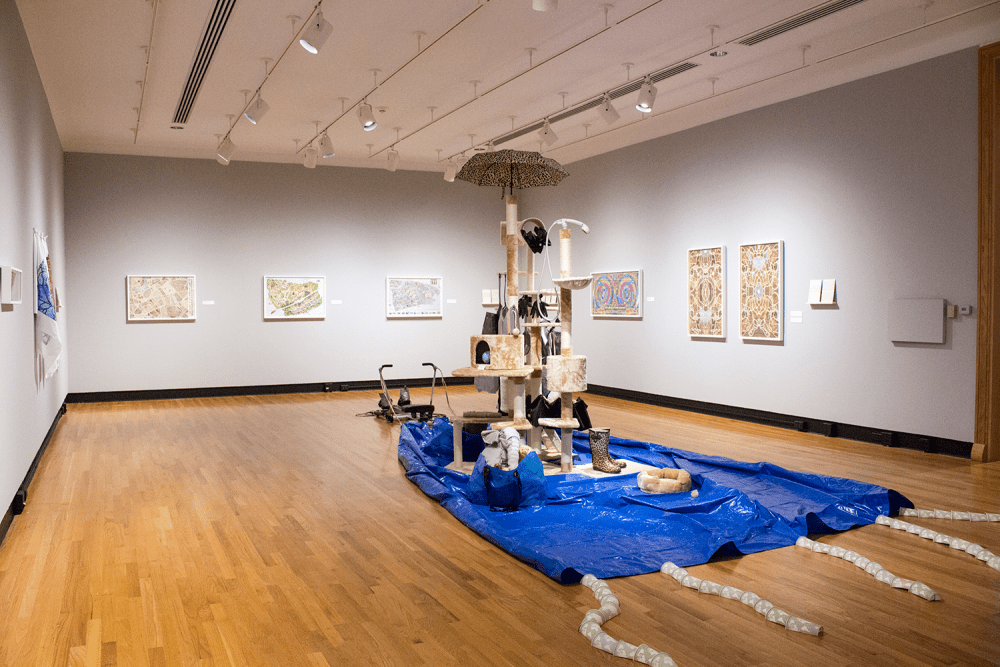

Purpura: At one point we played with the idea of incorporating the work of contemporary artists into the installation. We were going to work with five artists, but we were losing coherence and didn’t have the space or the time or the funds to do it right. I did organize an exhibition by one of the five artists, Allan deSouza, that was on view at the same time as World on the Horizon. Called Through the Black Country, deSouza’s installation was based on the expedition diaries of the artist’s avatar, Hafeed Sidi Mubarak Mumbai, a fictional Zanzibari traveler who sets out to explore London during the 2016 Brexit vote. The show’s biting humor and critique of the legacies of empire and fraught immigration policies in the UK today acted as a kind of interlocutor for World on the Horizon, connecting histories of diaspora and settlement to our present moment.

Allyson Purpura (PhD CUNY Graduate Center) is senior curator and curator of global African art at Krannert Art Museum, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Her research on Islamic knowledge practices in Zanzibar led to her current interest in the broader connections between knowledge and power, particularly as they play out in the representational practices of museums. In addition to her teaching and curatorial practice, Purpura has published on a range of topics including Islamic charisma and piety in Zanzibar, script and image in African art, “undisciplined” knowledge, ephemeral art, and the politics of exhibiting African art. Select projects include an award-winning reinstallation of KAM’s African art collection, and solo exhibitions with artists Wosene Worke Kosrof, Moshekwa Langa, Victor Ekpuk, Nnenna Okore, and Allan deSouza.

Elizabeth Rodini (PhD University of Chicago) works at the intersection of museums and academia, and has lectured and published widely on museum and collection history, museum scholarship, and cultural landscapes. As founding director of the Program in Museums and Society at Johns Hopkins University, she oversaw over 50 museum-university collaborations, resulting in exhibitions, educational initiatives, web projects, and programming. She has curated exhibitions at the Smart Museum of Art, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and the Walters Art Museum.

Rodini’s historical research centers on cross-cultural encounters in early modern Venice, particularly matters of object mobility, recontextualization, and reuse. Recent publications include “Imitation as a Mercantile Strategy: The Case of Damascene Ware,” in Typical Venice? Venetian Commodities, 13th-16th Centuries (Brepols, at press), and “Mobile Things: On the Origins and Meanings of Levantine Objects in Early Modern Venice,” Art History (2018). She is a member of the working team for Mobility of Objects across Boundaries, a British Arts and Humanities Research Council project, and pursued related work in the spring of 2018 as a visiting fellow at the Bard Graduate Center in New York City. She is currently completing a book-length study of Gentile Bellini’s portrait of Mehmet II, constructed as an object biography and methodological reader, and is launching a new project on the politics of heritage preservation.

Thanks to Kevin Dumouchelle and Karen Milbourne (NMAfA) for facilitating visits to the Smithsonian’s installation of the exhibition; Prita Meier, exhibition cocurator; and Christine Saniat and Julia Kelly (KAM) for their assistance with images.

- Thematic section texts—typically placed on gallery walls—help to structure, even pace, an exhibition. Together, they define at the broadest level the main subjects, ideas, or issues that an exhibition explores. Each section text provides both a context for the objects placed in a designated area of the gallery and a jumping-off point for closer looking. “Gang labels” are texts that call out some kind of connection or kinship between a group of objects in proximity (in a case, on the wall, and so forth) within a thematic section, while individual object labels speak to the specificities of a single object. This kind of interpretive “tiering” or “nesting” is effective largely because it helps reveal connections (between objects, ideas, narrative threads), and because it layers the stories, providing different entry points into the objects. If a viewer chose to read only the individual object label, she would still get a sense of how that object related to the larger story being told. ↩

- Paola Ivanov, “Beyond Consumption: Aesthetic Glorious Deeds and the Generation of Translocal Society on the Swahili Coast,” in World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean, ed. Prita Meier and Allyson Purpura (Urbana-Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum and Kinkead Pavilion, 2018), 217–34. ↩

- Aisha Khan, “Journey to the Center of the Earth: The Caribbean as Master Symbol,” Cultural Anthropology 16, no. 3 (August 2001): 271–302. ↩