The following essay by Virginia Maksymowicz and Blaise Tobia is part of “Beyond Survival: Public Support for the Arts and Humanities,” a call for reflections on and provocation about the precarious state of arts funding after decades of neoliberal economics and the long culture wars.

As Ted Berger, former executive director of the New York Foundation for the Arts, has insisted, we should “not have to reinvent the wheel every time there is a disaster, natural or economic. We have to think long-term and in more systemic ways.”

Create NYC, Mayor Bill de Blasio’s cultural plan for the next decade, uses the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act and its employment of artists as a case study for public funding of the arts and humanities. CETA was a federal program created by the Nixon and Ford administrations during a time of financial crisis in the mid-1970s. From 1973–80 (through Jimmy Carter’s presidency) approximately ten thousand artists were employed nationwide under CETA, at least six hundred of them in New York City, with the Cultural Council Foundation’s Artist Project (CCF) being the largest program. The CCF subcontractors included the Black Theatre Alliance, the Association of Hispanic Arts, and the Foundation for Independent Video and Film. Hospital Audiences, La Mama ETC, the American Jewish Congress, and the Theater for the Forgotten ran independent programs.

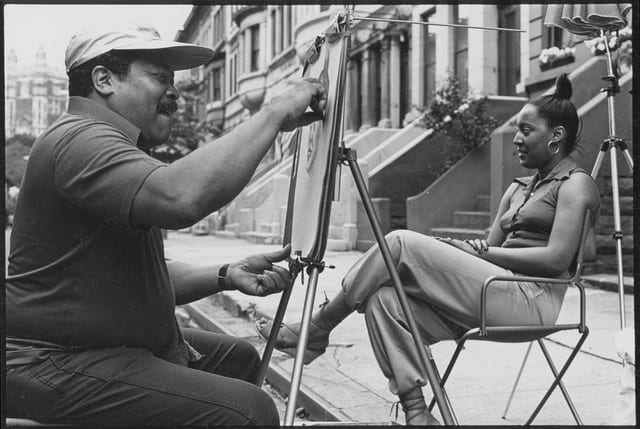

We artists were placed with hundreds of community sponsors for whom we taught classes, led workshops, created public artworks, gave musical, literary, and theatrical performances, and provided community documentation. We successfully negotiated “differing audiences, priorities, and compromises.” Among the organizations requesting one or more CETA artists were schools, cultural centers and museums, community centers, senior centers, civic and historical associations, and city and borough agencies. In exchange, we received a good salary, benefits, and one day per week to work in our studio or on independent creative endeavors. The various CETA programs were remarkably diverse in terms of ethnicity, age, gender, and sexual orientation — both in terms of the artists and administrators, and the communities served. Many of us went on to successful careers.

Overall, CETA was the largest employment program for artists since the Works Progress Administration of the 1930s. Its legacy, though not always recognized, is manifest today both in the cultural organizations that got their start with CETA funding and in the inclusion of social practice in the art world. In addition, the US Department of Labor’s report, “The CETA Arts and Humanities Experience,” documented a variety of positive, long-term financial benefits such as individual economic and skill development, economic and cultural development, and an increased understanding of culture as an industry.

Returning to Ted Berger’s observation, the wheel doesn’t have to be reinvented. However, it does have to be put back on its axle. How? By reinstating job programs like CETA and making their accomplishments known. By educating our government representatives about the cultural, social, and economic importance of the arts. By advocating for artists as workers who perform a service for the larger society. By emphasizing that government funding of the arts can be cost-effective and nonpartisan. And, in this politically polarized environment, by reminding them that CETA was developed and implemented by two Republican administrations and then continued under a Democratic one.

Now based in Philadelphia, Virginia Maksymowicz and Blaise Tobia are visual artists who were employed under the Cultural Council Foundation’s CETA Artists Project in New York City. Currently, they are part of a project to secure the legacy of the CCF CETA Artists Project on its 40th anniversary and have contributed to the cultural plan of NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio.

The next response in the Models and Case Studies chapter is “Meaningful Transformation” by Jules Rochielle Sievert.