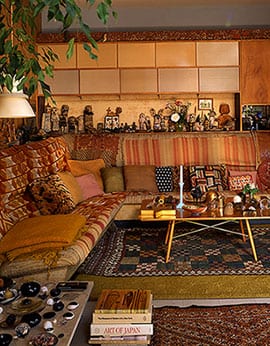

A photograph of the living room of the Eames house in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles has proven rather puzzling to historians of design. It depicts the famous Case Study House as full of exotic collectibles. Hopi kachina dolls, seashells, craft objects, silk textiles from Nepal and Thailand, and elaborately patterned rugs from Mexico and India all crowd and assault their modernist frame. Beatriz Colomina has commented on this “kaleidoscopic excess of objects” in the Eames house, and attributed it to Ray in particular, described elsewhere as a “sublime pack rat” who saved and collected everything.1 In the 1990s, the director of the Vitra Design Museum made a similar observation upon visiting the Eames office: “It seemed that I was being whisked into a world full of images from India, and at times into a circus.”2 Others have expressed their unease with this excess and the difficulty of assimilating this side of the Eameses into their identities as masters of mid-century modernism.3 How, then, should we understand this picture? Is it yet another scene of modernism’s insatiable consumption of the non-West, a photograph that belongs to the same family of images as the picture of tribal artifacts in Picasso’s studio? Or is it an expression of their postwar liberalism, an image consistent with the Eameses as advocates of a cosmopolitan and more “humane modernism?”4

In an essay concerned with the Eameses’ relationship to the discourses of craft, Pat Kirkham, author of an important book-length study of the Eameses, has argued for the latter; she has also gone far to reject the longstanding record of gender bias that has tended to hold Ray responsible for the clutter. Instead, she links the couple’s unorthodox collecting practices to the substantial influence on Charles of the American Arts and Crafts movement. According to Kirkham, the Eameses viewed the carefully composed arrangements of objects in their living room as “functioning decoration,” a concept which deliberately sought to overcome the banishment of decoration by modernism’s prevailing minimalist sensibilities, and which contributed to their unique aesthetic of “addition, juxtaposition, and extra-cultural surprise.”5 Kirkham thus calls for a more dialectical understanding of the relationship between crafts and industrial design in the postwar era and points, at least implicitly, to the way in which the Eameses’ fascination with the non-West remained inseparable from the hierarchies and binaries of art-craft, high-low, and male-female.

This essay will not be concerned with assessing whether the Eameses’ aesthetic of “extra-cultural surprise” was either humanistic or imperialistic in its posture or effects. Nor will it claim to provide an account of high modernism’s relationship to the discourses of craft, which fueled the postwar interest in the emergent category of “non-Western art” in a number of different ways. Instead, I will turn to the little-known circumstances of the Eameses’ relationship to India, in part to begin to dislodge the loaded terms of these equations, and in part to investigate some larger problems of historical understanding that emerge from these entanglements between East and West. The Eameses’ projects in India provide a dislocated setting through which to view their design ideas, and reveal how certain modern aesthetic principles were translated and interpolated into other idioms and contexts of the modern. By asking not merely how India fit into the work of the Eameses, but also how the Eameses fit into the ideologies and practices of the newly independent nation-state, my concern is to map a set of global arrangements that have been largely excluded from the prevailing narratives of mid-century modernism and postwar design. As I will show, the Eameses traveled extensively in the Indian subcontinent during the 1950s and 1960s, and participated in a range of projects in film, architecture, and exhibition design—at times successfully with enduring results, at other times less so, with contradictory results that point up the limits of their cross-cultural desires. By tracing the range of seemingly incommensurable interactions between the modernist canon embodied by the Eameses and the very different formations of the modern produced through a society such as India, I argue instead for a more global historiography of modernism itself, undertaken through a contextual and comparative relation to the archive and a disruption of its universalizing claims. The account of postwar modernism I seek to construct, in other words, is one that includes the modernizing agendas of the postcolonial nation-state, for the aspirations, visions, tensions, and contradictions that emerge in the latter, I will argue, are crucial to understanding the distinctly global culture of design that we find ourselves inhabiting today.6

Scholars have only recently begun to examine systematically the implications of the ethical and epistemological questions raised by non-Western contexts for the modernist canon in art and architectural history.7 In the case of Le Corbusier, for example, architectural historians have generally regarded the Swiss architect’s unexecuted projects for Algiers, developed between 1931 and 1942, after he received French citizenship, as masterpieces of modernism, discussing them at length in formal terms with little or no attention to their sociopolitical context. As Zeynep Celik has argued, however, it is not simply the legacy of nineteenth-century French discourses on the Orient or the Parisian avant-garde’s preoccupation with the non-West in the 1920s and 1930s that requires assimilation into the discipline’s canonical understanding of this episode.8 Le Corbusier’s plan for the Arab quarter, with its spatial separation between the indigenous and European inhabitants of the city, was an especially unsettling example of modernism’s urban image at this moment. Le Corbusier’s Algiers, had it been built, would be characterized by separation, hierarchy, and visual supervision, with appended space for “contact and collaboration” between the races. If his later plan for Chandigarh, the city born “without umbilical cord, in the harsh plains of Punjab,” according to one of India’s preeminent modern architects, produced fundamental and competing divergences between Le Corbusier and his client, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, then the plan for Algiers was undoubtedly much worse: it fulfilled all of the most damaging premises of colonial urban planning, which Frantz Fanon would later connect so unequivocally to violence, trauma, and psychic damage to the self, in his powerful anticolonial manifesto, The Wretched of the Earth.9

Critical interventions in architectural history have thus helped to deconstruct the heroism of a figure like Le Corbusier in places like Algiers, Chandigarh, Istanbul, and elsewhere. They have also confronted, more substantially, the tremendous historical complexities of modernism on the world stage at the middle of the previous century, for it is a historical moment which belongs simultaneously to nationalism and decolonization, modernism’s varied responses to colonialism, and the residues of orientalism of the nineteenth-century sort. It is useful to recall that Edward Said had cautioned against extending the arguments of Orientalism, rooted in the historical logic of the nineteenth century, to the complexities of the twentieth century precisely because he felt that his 1978 book could not account for the great political and cultural movements of decolonization within which modernism’s canon was produced. A “huge and remarkable adjustment in perspective and understanding” was required, he stated, to account for twentieth-century modernism’s postures and sensibilities, which led to the end of the era of colonial subjugation and a new self-awareness for many of those involved.10 Said was interested in a writer like Joseph Conrad precisely because he sat on the cusp of this threshold; it was the ambiguity and essential lack of clarity of Heart of Darkness that generated Said’s brilliant reading of the “two visions” made possible by the “complicated and rich narrative form of Conrad’s great novella.”11 Although the paradigms of Orientalism were quickly assimilated into the field of art history, and the study of nineteenth-century painting, in particular, Said-ian approaches to the twentieth century have received far less attention in the visual arts. For Said, Conrad’s method of spectral illumination and misty meaning-making, “as a glow brings out a haze,” marked not only the difficulty, confusion, and gloom brought on by the increasing inevitability of colonialism’s demise, it also represented modernism’s response to the erosion of an earlier epistemological ground (i.e., orientalism). Through such readings, and in much of his later work, Said sought an account of twentieth-century culture by placing modernism’s aesthetic forms, or at least its literary forms, the novel in particular, within the world-historical unfolding of decolonization and anticolonial nationalism in the twentieth century. How can we meaningfully extend these insights to the modernist canons of the visual arts? And what would it mean to rethink our account of “mid-century modernism” through the discrepant narratives of a postcolonial one?

The Eameses are perhaps, on first glance, an unlikely point of entry into some of these concerns and trajectories relating to postcolonial modernity because in many ways they serve to epitomize a story that is thoroughly American. Both Charles and Ray were born before World War I (he in St. Louis, and she in Sacramento) and were shaped by the political economy of the Depression and the New Deal. Charles’s design ideas were imprinted by his experiences in engineering and manufacturing, and by blue-collar jobs he held in the heartland, while Ray was influenced by early Abstract Expressionism during her time in New York in the late 1930s.12 They married and moved to Los Angeles six months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, where they joined an group of acclaimed Jewish émigrés from Europe to establish a robust aesthetic and intellectual culture in that city. Yet they also signaled a major departure from their peers in these Old World circles: the Eameses did not maintain a “high-cultural” distance from the forms of mass culture so unappealing to a contemporary neighbor like Theodor Adorno. Instead, the couple served to embody Southern California as a site for the “American Dream,” defined as the seductive mix of postwar prosperity, consumerism, television, freeways, and good weather.

This Americanness was stamped into all their contributions, from the Case Study House of 1949, heralded by Peter Smithson as “wholly original and wholly American,” yet somehow “through Mies,”13 to their famous furniture experiments with molded plywood and plastic, which “changed the way the twentieth century sat down,” according to the Washington Post.14 Their patriotism was perhaps most explicit in their exhibition work for the federal government, such as their show for the bicentennial of the American Revolution, The World of Franklin and Jefferson, which was panned as overly ideological by some critics (“What is this stuff doing at the Met?” demanded Hilton Kramer in the New York Times), or their multiscreen film for the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow, titled Glimpses of the USA.15 The latter, which projected over two thousand still and moving images onto seven huge screens hanging inside a Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome, was intended to convey “a day in the life of the United States.” It was viewed by some three million Russian visitors to the exhibition, which became famous as the site of another media spectacle, namely, the impromptu “Kitchen Debate” between Nikita Khrushchev and Richard Nixon, when the two leaders discussed their political differences against a backdrop of domestic appliances and the escalations of the cold war.16

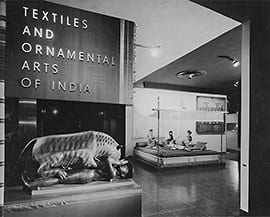

The Eameses’ first Indian project—a contribution to a 1955 exhibition titled Textile and Ornamental Arts of India at New York’s Museum of Modern Art—was also shaped by this cold-war picture. Placing still images of objects in the show against the dramatic sounds of an Indian raga, the Eameses produced a short film for the installation, which was designed by their friend, the architect Alexander Girard, and organized by Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., the director of industrial design at MoMA during the time of its “Good Design” exhibitions.17 Girard and Kaufman had traveled to India together in the fall of 1954 to survey and collect objects for the exhibition. “I had six weeks,” Kaufman explained apologetically,

in which to pick up a smattering idea of India and its crafts. Monroe Wheeler’s library and the Library and Museum at Cooper Union were mainstays; experts at the Metropolitan Museum and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts joined the Cooper Union staff in helping me cram. None of this could suffice to prepare me for the exceptional diversification of Indian textiles which I found, nor for their wide dispersion in the country, nor for the elephantine leisure with which India moves, when and if it moves. . . . Timing was one block. Another was the newness and stiffness of the Central Government. . . . India is facing a gigantic, controlled conversion to industrialization.18

Kaufman was particularly excited by loans he had secured from the major museums in Delhi, Bombay, and Calcutta, along with numerous private lenders, because they represented items that were “truly Indian in design” in contrast to the “export” wares, which he felt had “dominated Western collections up to now.”19 But Kaufman resigned before the opening of the show, passing the design directorship on to Monroe Wheeler. The preparations had coincided with the opening of his infamous MoMA exhibition The Family of Man, which presented “the essential oneness of mankind throughout the world” through the photographic selections of curator-photographer Edward Steichen.20 If the latter exhibition offered up postwar America as part of an integrated global unity through a portraiture that valorized difference and erased inequality, then the former was similarly mired in the ideological agendas of the time: the intention of the India show, according to Kaufman, was to improve India-US relations, especially given “the urgency with which India today, independent and industrially bourgeoning, was being courted by both parties in the cold war contest.”21

The exhibition thus revealed America’s fears about India’s alliances in the cold-war struggle, fears that would only escalate that year because of an event taking place in another part of the world. The event was the Bandung Conference, the emotionally charged meeting held in Bandung, Indonesia, that brought together twenty-nine newly liberated countries of Asia and Africa, the self-declared “underdogs of the human race,” in response to the bipolar politics of the cold war.22 The goal of the meeting, in the words of its host, the Indonesian president Sukarno, was to “inject the voice of reason into world affairs,” through a new alliance of “third” or “non-aligned” nations united by their commitment to peace, and their shared histories of colonial and anticolonial struggle.23 The meeting represented, in other words, the spirited beginnings of the “Third World” ideological project and its foreign-policy counterpart, the Non-Aligned Movement, which was formalized by Nehru of India, Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, and Josip Tito of Yugoslavia in 1961, and viewed as a provocation by the cold-war powers.

Although art historians have increasingly turned to the impact of cold-war discourses on the visual arts, the global implications of an event like the Bandung Conference have not been part of this revisionist project, which in its account of cold-war culture continues to privilege the art-historical divide between a dominant prewar France and American hegemony after the war.24 Here, Okwui Enwezor’s ambitious attempt to archive and exhibit the modes of cultural self-awareness that found expression in Africa in this postwar period, which reshaped for African nations a “short century,” is a noteworthy exception. Enwezor’s lesson, for our purposes, is that the radical transformations of the world in the postwar period cannot be understood outside the agency and autonomy of Africa’s liberation struggles and the new conceptions of self and society that found expression in events like the Bandung Conference. These social processes generated, in Enwezor’s terms, a fundamental change in the Western conception of the universal subject, “challenging and transforming the ontological limits imposed by European hegemony.” As such, they remain a “strong knot in the tangled web of the modern condition,” and demand a revision of the metanarratives of the twentieth century.25 Two crucial questions, raised by Enwezor and by discussions in postcolonial historiography more generally, thus serve to inform the present investigation: How are modernist practices and forms of representation in the postwar period linked to “other” ideas about history and agency, culture and progress, and sovereignty and nationhood, which were unfolding in dialogue and dissent with the dominant practices of the era? And what is the relevance of this historical matrix for our understanding of modernism, and indeed the world, today?

Three years after the Bandung Conference, in 1958, Nehru, the first prime minister of independent India, invited the Eameses to help the developing country incorporate design into his project of national regeneration. Before elaborating, however, I want to attend more closely to the summer of 1955, when the self-assertions of the former colonies at the Bandung Conference converged with the arrival of Indian art and aesthetics into public consciousness in the United States. The Textile and Ornamental Arts of India exhibition at MoMA had gathered an unprecedented range of textiles, crafts, and decorative objects from collections and institutions around the world, including several hundred loans from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, such as the highly symbolic Tipu’s Tiger, seized by the British in 1799 and still displayed at the Victoria and Albert in London.26 Tellingly, American audiences were largely indifferent to this contested symbol of imperial rule; they responded instead to Girard’s installation of brightly colored saris from different regions of the subcontinent, which hung over a fifty-foot pool of water and were reflected for the viewer in a large mirrored wall. Visitors did not appear to object to this or other violations committed by Girard to the sanctity of MoMA’s modernist “white cube” space. Indeed, his installation, designed as an imaginary bazaar, received rave reviews in New York’s fashion magazines and, intentionally or not, helped to establish the village scene as the privileged setting for the display of Indian crafts in the postwar period.

MoMA’s Textile and Ornamental Arts of India thus received significant attention by the mainstream media and was featured in Life, the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, Women’s Wear Daily, and Harper’s Bazaar, before traveling for the next three years to more than a dozen locations in the United States, ranging from Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Tennessee, to Texas, California, Florida, and Hawaii. The exhibition also brought the Eameses into contact with a number of distinguished “experts” on Indian art, including Stella Kramrisch, the Austrian professor and curator of Indian art who had recently arrived to work in Philadelphia, Pupul Jayakar, the writer and cultural activist known for her advocacy of crafts in Indian society, and John Irwin, the Keeper of the Indian Section at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It is more than a simple coincidence that all of these authorities on Indian art would converge on the MoMA show, the first large-scale exhibition of Indian culture in the United States. They were, more accurately, pioneering figures in an international art world that had been ideologically and politically transformed by the realities of cultural sovereignty in the subcontinent, who possessed a spirited sense of mission, simultaneously nationalist and internationalist, in relation to the visual arts. The role of this first generation of postcolonial art practitioners was to consolidate and institutionalize knowledge about Indian art for the first time on this new global stage, which was also defined by a growing American hegemony and New York’s increasingly unrivaled status as the epicenter of the modern art world. Nevertheless, the friendship between Jayakar and the Eameses that was first established here continued over the next three decades, resulting in a number of dynamic collaborations and initiatives that I will continue to explicate throughout this essay.

To accompany Textiles and Ornamental Arts of India, MoMA had organized a music, dance, and film program that was especially well received by the press. It included the American debuts of the master sarod player, Ali Akbar Khan, and the legendary Bharatnatyam dancer Shanta Rao. Significantly, the program culminated on the final day in the world premiere of Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali. The Bengali director’s first film, which inaugurated the Apu trilogy, received international critical acclaim and established the paradigm for a progressive Indian art in the first decade after Independence.27 Although Ray did not attend the New York premiere, he wrote in his memoir, My Years with Apu, of the rush to complete the film on time and the suspense in Calcutta as he waited for the response to the screening from Monroe Wheeler at MoMA.28 The telegram, declaring the film “a triumph of sensitive photography,” came three weeks later, according to Ray, and it set in motion a set of events that forever changed his life and work. Half a century later, the event, along with Ray’s own recollections, is s from the wider context of lore surrounding this legendary cinematic figure. The “memoir” recalling this episode was, for instance, reconstructed from the notes for an unfinished draft, written by his widow several years after his death.29

Nonetheless, Ray’s adaptation—famously influenced by French and Italian Neorealism—of the 1929 Bengali novel by Bibhuti Bhushan Bannerjee about a young boy, Apu, and the changes experienced by his village in Bengal evoked a set of iconic, liberal-secular symbols for the transformations occurring in newly independent India. Although Ray’s distinct brand of poetic realism, which the Japanese master of cinema Akira Kurosawa praised as the “river-like flow” of his films, would later be criticized for its distance from the political, it signified to the world in the 1950s a “principled stand on cultural expression, its economy being its gesture of refusal,” and revealed his confidence in the value of the modern as he negotiated a vernacular cinema into a world cinema, a “seminal repositioning” for cultural practice in the subcontinent.30 While interpretations of Ray’s Bildungsroman of Bengal vary a great deal, scholars of Indian cinema tend to agree on the trilogy’s status as “one of the artistic pinnacles of a specifically modernist art enterprise inaugurated by post-war Nehruite nationalism.”31 What precisely is meant by this “post-war Nehruite nationalism,” epitomized by Ray’s early cinema, will become clearer as I turn to investigate the Eameses’ next set of involvements with India. For now, it is important to observe the spirited cosmopolitanism of the summer of 1955 in New York, when a variety of modernist forms and expressions—in dance, music, cinema, and the visual arts, shaped by Indian artists and writers, and an international community of curators and scholars empathetic to this emerging vanguard—came together at MoMA, the citadel of modernism, in defiance of the hard separation between “craft” and “fine art” that was the dubious inheritance of colonial art institutions. Energized by the acts of self-assertion on the part of the “underdog nations” occurring simultaneously in Bandung, the novelty of this historic exhibition is that it appears to have deflected, if only for the moment, the fate of Indian art within what James Clifford has called the “art-culture system,” that structure of overdetermination that has for too long decided the value of non-Western art as it enters into the Western museum.32

When the Eameses arrived in India in 1958, they joined a growing cadre of Western architects and designers, including Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn, Richard Neutra, and Grace McCann Morley—the American woman who left the San Francisco Museum of Art to become director of India’s first national museum—who had all responded to the urgent call by the new nation-state to assist with its modernizing projects.33 The moment had arrived, as Nehru stated in his famous “Tryst with Destiny” speech delivered on the eve of independence on August 14, 1947, “which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.”34 Nehru’s words also signal what Partha Chatterjee has identified as the “moment of arrival” in the development of nationalist thought in India, the “final, fully mature” ideological form, which transformed nationalism into state practice and claimed a conception of social justice, however limited, as its legitimizing principle.35 Nehru’s hubris was to believe that India could catch up in its delayed modernity by accelerating the pace of industrialization—by building new dams, offices, iron and steel plants, factories, airlines, and cities at a historically unprecedented rate. Buoyed by Nehru’s intelligence and optimism (and the death of Mahatma Gandhi, for the latter’s anti-industrialism and emphasis on the primacy of India’s village society were a far cry from Nehru’s plan for aggressive development), the nation set out to reinvent itself with an almost evangelical zeal. Indeed, Nehru’s statement that the nation’s hydroelectric dams were the new “temples of modern India” perhaps best captures the spirited, secular drive of this moment, not to mention the irony that its righteous awakening was to be realized through the authority of science.36

In relation to modern art and architecture, part of the challenge of the Nehruvian vision was to liberate design from its traditional association with colonial art education under the British. As I have elaborated elsewhere, the four major art schools established by the British in India during the nineteenth century were part of the wider program for “cultural improvement” in the colony; they served to institutionalize a sharp distinction between “fine arts,” on one hand, defined as Western-style painting and sculpture, and the sphere of Indian crafts, on the other, defined as the aesthetic output of the Indian village.37 Design, in other words, until the time of independence was promoted as the traditional arts and crafts of the village and distinguished against industrial production. Moreover, the nationalist response to such a distinction in the first half of the twentieth century, in the form of the swadeshi movement and Gandhi’s khadi campaign emphasizing homespun products for a self-sufficient India, did not present any real challenge to the terms of the aesthetic divisions established in the colonial period.38

In response to this history, Nehru set out to forge a new relationship between design and industrial modernity for the decolonizing nation, one that was driven by an overriding concern, as I have noted, with the problem of India’s “belated modernization.” The Eameses were thus enlisted to assist with this challenge, along with a host of other scientists, engineers, designers, and architects from Europe and North America. But the goal was not simply to emulate the West or adopt its modernist styles and designs. Nehru’s investment in modern architecture and design was, as Vikramaditya Prakash has argued in his account of Le Corbusier and the city of Chandigarh, ultimately instrumental, privileged by the leader not because he believed in art for art’s sake, but because he saw design as a catalyst for change, newness, and creativity for Indians. In Nehru’s words:

The main thing today is that a tremendous amount of building is taking place in India and an attempt should be made to give it a right direction and to encourage creative minds to function with a measure of freedom so that new types may come out, new designs, new types, new ideas, and out of that amalgam something new and good will emerge.39

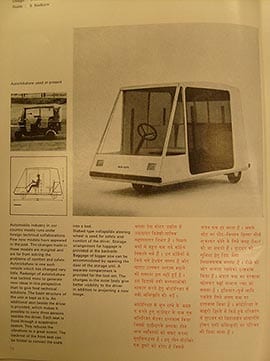

That something “new and good” would emerge out of “right direction” and “creative minds” is perhaps best represented in architecture and design journals of the period, which the Eameses studiously collected for their files. Proposals for “improving” the design of such subcontinental classics as the auto-rickshaw, the tiffin lunch box, and devanagri script, for example, serve to communicate the problem-solving spirit of the Nehruvian era, and the role of the specific conundrum that would be increasingly understood as “design in a developing society,” or design in an Indian idiom.40 Although Nehru’s sense of urgency summoned young architects and designers to think big and take risks, the general euphoria of the era did not, in hindsight, enable them to debate issues at length, or “evolve a theoretical approach to design,” leading to the much greater problem in the Indian case of an absence of criticism and theory within modernism, that is, a modernism characterized by “triumphant instrumentality” without the disjunctures of an avant-garde, “at best a reformist modernism.”41 The most powerful response to this problematic legacy is undoubtedly the foundational intervention made by Geeta Kapur, who has effectively managed to highlight this lack, and many of the substantive and theoretical issues it raises, through her short but haunting rhetorical question, “When was modernism in Indian art?”42

In 1958 the Eameses spent five months traveling in India, funded by the Ford Foundation, in order to produce a commissioned report on the future of Indian design. They visited factories and villages and met with artists, craftsmen, intellectuals, and government officials—including Nehru and his daughter, Indira Gandhi—to familiarize themselves with Indian design traditions, especially those related to everyday objects. Ray Eames reflected on the experience in an interview some two decades later: “Charles and myself,” she explained, “toured all over India, finally stopping at the Hotel Cecil near a whitewashed mosque, and in 125 degrees in the shade, wrote a report called the Eames Report. . . . The report was inspired by the many bright children we saw in the villages—curious, open, active, beautiful young people with tremendous potential.”43 The Eames Report or The India Report (1958), which began with a passage from the Sanskrit philosophical text, the Bhagavad Gita, recommended “a sober investigation into those values and those qualities that Indians hold important to a good life.”44 As Ashoke Chatterjee, a leading figure in Indian design, has written, “Government officials were expecting a feasibility report. What they got was an extraordinary statement of design as a value system, [and] as an attitude that could discern the strengths and limitations of both tradition and modernity . . .”45 The Eameses argued in the report for an assessment of “the evolving symbols of India” and the need to connect these values and symbols to “the problems of environment and shelter,” services and objects, and solutions to these problems “in theory and actual prototype.” The task of translating India’s symbols and values into concrete details would be “difficult, painful and pricelessly rewarding,” they acknowledged, but in light of the dramatic rate of change in Indian society, that task was more urgent than ever before.46

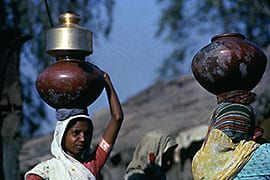

Jayakar, who contributed to the catalogue of the Indian textile show at MoMA and was responsible for introducing the Eameses to Nehru, described the meeting in which the couple presented their report to government officials as “unforgettable.” Charles Eames began quoting from the Bhagavad Gita; when puzzled government ministers sought feedback on industrial design. “There was utter chaos of communications,” she wrote.47 The report itself also reflects some of the discrepancies and missed communications of this encounter. Charles’s fetishization of the lota (or water vessel), which he called “the greatest, most beautiful” object “we have seen and admired during our visit to India,” and which he documented in hundreds of photographs, for example, elevated this everyday object to the highest of design ideals. “How would one go about designing a lota?” he theorized in the report, offering a list of twenty-some details, from the mathematical to the phenomenological, relevant to its construction.48 The lota was chosen, according to Ray, “as a fixed symbol of utilitarianism in an evolving pattern of design. It could have been anything else from the day to day lives of the people.”49 Unfortunately, the cultural association in the subcontinent of the lota with defecation, hygiene, and washing oneself appears to have eluded the couple, and Charles later included his discourse on the lota in his lectures and slide-shows at Harvard and elsewhere.50 The lota would eventually appear, along with the quote from the Bhagavad Gita, on the couple’s Christmas card during the holiday season back in Los Angeles.

Significantly, The Eames Report also recommended the establishment of a permanent institute for design in India as a “steering device” in the “relentless search for quality.” The integrity and quality of design, the couple wrote prophetically, “must be maintained if this new Republic is to survive.” The future lay in the training of students, they argued, who seemed “much brighter than their designs”; the student’s drawings were, regrettably, in India in the 1950’s, “an assemblage of inappropriate clichés.”51 Nehru’s response was to establish the National Institute of Design in 1961 in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, a city that resonated, paradoxically, with a history of nonindustrial design practice, as India’s textile capital and the site of Mahatma Gandhi’s ashram, where the latter led the nation in his boycott of industrially produced British goods. Nevertheless, the National Institute of Design, or NID, the direct result of The Eames Report, was the first attempt by a developing country to use the design principles inherited from the Bauhaus as a tool for national regeneration; it remains one of the premier cultural institutions in India today, setting the pedagogic standard for most other design schools in the country.52 Moreover, the Eameses’ attention to what they called the “vernacular expressions of design” and to “everyday solutions to unspectacular problems” reflected their awareness of the specific dilemmas of design in a rapidly industrializing, ancient society—dilemmas which are by no means resolved in India in the twenty-first century, a point to which I will return at the end of this essay.

After Nehru’s death in 1964, the Eameses returned to India for three more months to plan, in conjunction with students and staff at the NID, a memorial exhibition about the man they had greatly admired. According to Ray Eames, the couple thought “long and hard about how you treat the life of such a great man conceptually.”53 The exhibition that resulted, Nehru: His Life and His India, incorporated some twelve hundred photographs, plus fabrics, art objects, and sound, as well as a re-created jail cell featuring Nehru’s prison writings. Deborah Sussman, from the Eames Office, described working in Ahmedabad on the project: For several months, “seven days and seven nights, interrupted by occasional fevers, our lives were submerged in the exhilarating, often maddening process of designing and building the exhibit. . . . Ray had been there most of the time, valiantly coping with the difficulties of life in India. . . . She subsequently became a vegetarian.”54 The Nehru exhibition was a great success when it opened at London’s Royal Festival Hall in 1965 and was visited by some ninety thousand people, including the sole survivor in the Nehru family, Indira Gandhi.

In her biography of Indira Gandhi, Jayakar reported that she seemed “dazed after her father’s death,” unable to fully register the loss.55 According to Jayakar, the memorial exhibition gave her a focus, an “immediate plan” which she discussed “with passion,” in part because she feared that an incoming government might create “a new interpretation” of Nehru’s legacy.56 By the time the exhibition traveled to New York, Washington, and Los Angeles in 1966, Mrs. Gandhi would herself be sworn in as India’s first female prime minister, accepting the mantle of leadership from her father. The young Indira’s concern with managing and interpreting the legacy of Nehru is revealing, because it was partly such a preoccupation that would play into her misguided censorship measures of the “Emergency” (1975–77), in which democratic rights and freedom of speech were suspended under her order, and coercive methods sanctioned by the state, for almost two years.57 Nonetheless, she attended the opening of the Eameses’ exhibition about her father in Washington in her official capacity as Indian prime minister, and was photographed there with Jacqueline Kennedy, a woman whose own loss in 1963 mirrored that of India’s grieving daughter; the image of the two women played on the emotional links between them and their dynastic first families. The Nehru exhibition finished its run in the Eameses’ own city, Los Angeles; it came to India in 1972, where parts of it remain on permanent display at the Pragati Maidan in New Delhi and the Nehru Center in Bombay.

Many of the design aspects of the Nehru exhibition, especially the time-line and historical events panels—later known as the Eameses’ “history walls”—became part of the couple’s signature style. The panels depicted the events of one decade and presented Nehru’s biography as intertwined with the history of the new nation-state. The first panel, for instance, “The India into Which He Was Born,” began with the 1880s, the next, “Childhood in Allahabad” recounted the 1890’s, and so on, eventually proceeding through such themes and events as nationalism, freedom struggle, Nehru’s relationship to Mahatma Gandhi, satyagraha (or the doctrine of nonviolence), the attainment of independence, and the Non-Aligned Movement. The result was an epic yet linear story that inevitably left the viewer in awe of Nehru’s heroic leadership. Oddly, in their story of India’s Nehru, the Eameses did not deploy more advanced technologies used in their other exhibitions, like video, film, or multiscreen projection, a great irony given the technological aspirations of the Nehruvian vision. Instead, Charles argued to keep the exhibition simple “for Nehru/Gandhi’s sake,” an assumption that collapsed the notorious gulf between the two leaders on the question of technology, while also mounting a large installation about “Indian weddings” at the point in the history wall recording Nehru’s marriage.58 Here the couple seemed unable to contain their fascination with the exotic rituals of an Indian wedding, and they surrendered to the seductions of an anthropological gaze.

In hindsight, it is additionally meaningful that in 1965 the Eameses’ Nehru memorial exhibition did not find a home at MoMA in New York. It was mounted instead at the Union Carbide Building on Park Avenue, from January to March 1965. The Eameses’ exhibition was undoubtedly a public-relations coup for Union Carbide, the American corporation that had recently joined India’s government-sponsored “Green Revolution” by establishing fertilizer factories throughout the country. Needless to say, public relations would never again be the same for the company after the disastrous 1984 accident at Union Carbide’s pesticide plant in Bhopal, where five tons of toxic gas seeped out of the plant in a thirty-minute period, killing almost four thousand people and permanently injuring tens of thousands more. While much more can be said about this catastrophe—widely regarded as the worst industrial accident in history—it symbolizes for our purposes the ever-widening gulf between the modernizing ideals of the Nehruvian era and the realities unfolding on the ground in India. The Eameses could not have anticipated that Union Carbide would come to stand for the most devastating aspects of industrialization and the Indo-American relationship, or that the Nehruvian dream enshrined in their memorial exhibition might lead to the nightmare of Union Carbide in Bhopal. Indeed, the couple seemed too distracted by the task of commemoration to view the signs of crisis that emerged in the wake of Nehru’s death. Indira Gandhi, for her part, sought refuge in her study where she was reportedly found during this period “curled up in her Eames chair.”59 It is important therefore to further situate the late 1960s and 1970s in India, in order to understand and critically assess why the Eameses’ hopes for the country remain in large part unrealized, and how their liberal vision of industrial design has, paradoxically, reemerged in recent years to serve the needs and desires of India’s neoliberal turn.

The period following Nehru’s death was marked by a growing climate of disaffection with the dreams of official modernization, resulting from the failure of Nehru’s economic plans, the increases in population, poverty, and illiteracy, and the rise of student movements in solidarity with the 1968 generation in Europe and America. Artists and intellectuals in South Asia were particularly disillusioned by the continued catastrophic effects of partition in former East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) and, eventually, the crisis of the 1975–77 “Emergency,” when, as I mentioned, democratic rights were suspended by Indira Gandhi, who announced that such stringent measures must be taken “just as bitter pills . . . administered to a patient in the interest of his health.”60 In 1970 J. S. Sandhu, an early advocate of “inclusive design,” wrote a long report to Charles Eames to ask for his guidance in navigating what Sandhu viewed as a series of visibly dangerous trends. The problem, he stated, was not just a gap between The Eames Report and its implementation, in part a manifestation of “the fatalism and inertia that are deeply engrained in Indian society,” but that India had at best achieved something akin to “symbolic modernization.” For Sandhu, such a conceit was epitomized by Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh, “the most un-Indian and expensive of cities,” which had failed to respond to the needs of the rural masses, and was a “sad reflection of the priorities and value systems of the leadership.” The future of Indian design, he argued, would be in a reorganized design profession committed to a much wider social demographic, and in a greater investment in design education “as a matter of social priority.”61 But the Eameses did not seem to know how to respond to the failures of the Nehruvian vision or the pleas for assistance that came throughout the 1970s from friends and institution-builders like Jayakar, and Ashoke Chatterjee at the NID. Meanwhile, trends in America—like feminism, Pop art, and the antiwar movement—increasingly placed the Eameses, with their public identity as apolitical and nonideological, on the margins of the avant-garde. Their final exhibition in the United States, The World of Franklin and Jefferson (1971–77), which the couple viewed as their crowning achievement and which brought the paradigm of heroic national leadership developed for their Nehru show to the grand narrative of American nationhood, was also among their least successful. In an era of social crisis and disillusionment with the US government caused by the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, and Watergate, the exhibition’s corporate sponsorship, along with its populist account of the Revolution and upbeat message about westward expansionism, simply did not fly.62

Charles also cautioned, in a long letter to the organizers when the Nehru show returned to India in the 1970s, against turning the exhibition into some “tasteless Chamber of Commerce pitch.”63 His concern was no doubt a response to a growing trend of the time toward a commercial orientation for cultural exhibitions and the emerging modalities of the international trade fair. By the end of the decade, the first Festival of India—a spectacular showcase of Indian art in Britain heavily promoted by Indira Gandhi and Margaret Thatcher—inaugurated a new era of exhibition culture, both a sign and a symptom of the increased competition among developing nations in the emerging neoliberal global economy.64 There are hints in the archive that the spectacular showcase of the Festival of India, with its goal of imprinting a new era of “Indo-American dialogue,” as stated by the Eameses’ old friend-turned-festival chairperson, Pupul Jayakar,65 was not the kind of show Charles would have liked. But it is difficult to know with certainty due to his death in 1978, which was, in the words of one obituary from the subcontinent, “an irreparable loss to India too.”66 The NID in Ahmedabad posthumously established an endowed fellowship and design award in his honor: it is sometimes referred to in an ironic manner as the “Eames Chair” in memory of his pioneering vision.

This other Eames chair—the NID award in Ahmedabad—is an apt motif for the nearly three decades of involvement by Charles and Ray Eames in the Indian subcontinent, until now overlooked in the growing scholarship on mid-century modernism, or presented in the hagiography as an eccentric aside. Yet the Eameses’ involvements with India span a remarkable period of historical change, and the various activities, projects, and relationships they forged provide a glimpse of the successive contexts, mutual dependencies, and competing agendas that have characterized the cold war, decolonization and its modernizing projects, the social crises of the 1960s and 1970s, and the beginnings in the 1980s of the restructuring of the new global economy. The Eameses’ internationalism was clearly made possible by the rise of American cultural hegemony in the world, which, as Serge Guilbaut has argued in the case of Abstract Expressionism, consolidated itself in the postwar period in the new alliances and values of the New York art world.67 As I suggested at the outset, however, the exotic objects collected by Charles and Ray along the way do not merely represent another moment in modernism’s insatiable appetite for the non-West; nor can their presence be adequately understood through the lens of an early-twentieth-century primitivist paradigm. The new world order of decolonization that led the Eameses to the subcontinent in the first place dramatically transformed the historical equation and presented a new horizon of agencies and possibilities for sovereignty and citizenship for the countries of Asia and Africa in the postwar period. In their response to the modernizing projects of the Nehruvian era, their humanist commitment to enabling India’s modernity, and their uneven attempts to comprehend the vexed questions of design in the subcontinent, the Eameses in India represent both the beginnings of an era of US hegemony, and a set of creative aesthetic responses to it, a paradox that was ultimately expressed and codified in their design manifesto and ethical vision for the new republic, The India Report of 1958.

More than fifty years later, The Eames Report has acquired something of the status of scripture in India, and it is frequently cited in the explosion of contemporary discourses surrounding design, in spite of its sentimental identification with the vernacular embodied by Charles’s preoccupation with the lota. The new visibility of design in India is undeniably linked to the centrality of new media, digital technologies, consumerism, and advertising to the neoliberal economic revolution that has meant an unprecedented expansion of the consumer class, but that has nevertheless excluded the large swath of the population that remains in poverty. In 2007 the government articulated a new set of design ideals, radically different from the socialist paradigms of the Nehruvian era, in an official National Design Policy, which posited as one of its main goals the “global positioning and branding of Indian designs” within the international marketplace.68 The self-stated ambition of the policy is to “outsource design,” and to promote the phrase “Designed in India” as a symbol of innovation and quality, in contrast to “Made in India,” which hints of cheap labor and poor production quality. As one Indian journalist noted, every iPod carries the inscription “Designed in the USA, built in China,” which underscores Apple’s “justly deserved reputation for understanding the value of design and its relevance to corporate strategy.”69 In the area of design, the journalist argued, India should aspire to the global success of the iPod, a mission which the Eameses as the architects of India’s first policy statement on design would have endorsed. In other words, the problems of American hegemony in design that the Eameses simultaneously represented and confronted during the 1950s persist in powerful ways in an era in which design innovation is increasingly bound up with corporate strategy and the dreams of US-led capitalism on the world stage, as symbolized by the example of the iPod.

In contrast to arguments about the value of design for global economic success, and the reception in India, for instance, of Richard Florida’s contentious, best-selling books on the economic role of the “creative class,”70 prominent theorists in India have also returned to the Eameses’ vision of the designer as a facilitator who empowers social groups and more broadly to their program for a socially conscious design to confront the homogenizing forces of globalization.71 To such thinkers, the Eameses’ conception of design as a bridge between the traditional and the modern has a new urgency and resonance in the face of a growing gulf between the urban, international locations for design, and the rural, vernacular basis of India’s craft communities. They point, in other words, to a set of possibilities emerging from The Eames Report different than those adopted as corporate strategy in the interest of quality, profit, and the outsourcing of design. How these varied uses and abuses of the Eameses’ legacy in India will enhance or hinder the nation’s aspirations for design, or serve to activate the social conscience of its public, is something that is continually unfolding and remains, of course, to be seen.

In the end, however, these sorts of concerns cannot be said to belong specifically to India. They point instead to the larger dilemmas that Hal Foster has linked to the new “political economy of design” in his self-described diatribe against the “tight consumerist loop” of contemporary design, Design and Crime.72 For Foster, the inflation of design, where “everything from jeans to genes seems to be regarded as so much design,” has followed the “spectacular dictates of the culture industry, not the liberatory ambitions of the avant-garde,” and it appears to reach its point of excess at the moment of its globalization, as in the turn to the cities of Asia by Rem Koolhaas, or the worldwide implications of the Bilbao effect, “likely to come to your hometown soon.”73 My account of Charles and Ray Eames in India has been an attempt to situate these contemporary processes within the long global career of design itself, and to map the specific contours and limits of a dialogue between two very different utopian investments in modern design (i.e., American and Nehruvian) in the middle of the previous century. My study is by no means a dismissal of the Eameses, but rather a bid to reposition their significance, at least partially, in this neglected episode of their career. My argument has been that the Eameses’ involvements with India make visible a set of historical interconnections between a postwar modernism and the particularities of a postcolonial one, which allow us to sketch a more global genealogy in response to the needs of our ambiguous present.

Saloni Mathur is associate professor of art history at the University of California, Los Angeles. She is author of India by Design: Colonial History and Cultural Display (University of California Press, 2007), editor of The Migrant’s Time: Rethinking Art History and Diaspora (Yale University Press/Clark Art Institute, 2011), and coeditor (with Kavita Singh) of No Touching, Spitting, Praying: Modalities of the Museum in South Asia (forthcoming, Routledge India).

I am grateful to the people and resources of the Clark Art Institute, the UCLA Center for the Study of Women, and the Getty Research Institute for supporting different stages of this project. Thanks also to David Hertsgaard at the Eames Office for his generous assistance with the images.

- Quoted phrases are from Beatriz Colomina, “Reflections on the Eames House,” and Joseph Giovannini, “The Office of Charles Eames and Ray Kaiser: The Material Trail,” in The Work of Charles and Ray Eames: A Legacy of Invention, ed. Donald Albrecht (New York: Harry Abrams, 1997), 144 and 45, respectively. ↩

- Alexander von Vegesack, preface, The Work of Charles and Ray Eames, 7. ↩

- See for example Pat Kirkham, Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995), 183. ↩

- Donald Albrecht, introduction, The Work of Charles and Ray Eames, 16. ↩

- Pat Kirkham, “Humanizing Modernism: The Crafts, ‘Functioning Decoration,’ and the Eameses,” Journal of Design History 11, no. 1 (1998): 25. The idea of “extra-cultural surprise” as part of the Eames aesthetic appears to begin with Peter Smithson, “Just a Few Chairs and a House: An Essay on the Eames-aesthetic,” Architectural Design 36 (September 1966): 443–46. ↩

- See Karen Fiss, “Design in a Global Context: Envisioning Postcolonial and Transnational Possibilities,” Design Issues 25, no. 3 (2009): 3–10; and Hal Foster, Design and Crime and Other Diatribes (London and New York: Verso, 2002). ↩

- See Esra Akcan, “Critical Practice in the Global Era: The Question Concerning ‘Other’ Geographies,” Architectural Theory Review 7, no. 1 (2003); and Kobena Mercer, ed., Cosmopolitan Modernisms (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005). ↩

- See Zeynep Celik, “Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism,” Assemblage 17 (April 1992): 58–77; and Celik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations: Algiers under French Rule (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997). ↩

- Charles Correa quoted in Vikramaditya Prakash, Chandigarh’s Le Corbusier: The Struggle for Modernity in Postcolonial India (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 32. See also Franz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (New York: Grove, 1965). ↩

- Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage, 1993), 293. ↩

- Ibid., 22. ↩

- Giovannini, 48–58. ↩

- Smithson quoted in Colomina, 127. ↩

- Cited in Albrecht introduction, 15. ↩

- Hilton Kramer article quoted in Helene Lipstadt, “Natural Overlap: Charles and Ray Eames and the Federal Government,” in The Work of Charles and Ray Eames, 166. ↩

- Ibid., 160–66. ↩

- Mary Anne Staniszewski, The Power of Display: A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998). ↩

- Edgar Kaufman, Jr., “Preliminary Report on the Indian Voyage,” Department of Circulating Exhibitions Records, II.1.83.2.1, Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, 2. ↩

- Edgar Kaufman, Jr., letter to Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, Chairman of the All-India Handicrafts Board, October 25, 1954, Department of Circulating Exhibitions Records II.1.83.2.1, Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. ↩

- Edward Steichen, introduction, The Family of Man (New York: MoMA, 1955), 4. See also Eric Sandeen, Picturing an Exhibition: The Family of Man and 1950’s America (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995). ↩

- Edgar Kaufman, Jr., Preliminary Report on the Indian Voyage, 1. See also Donald Albrecht, “Design Is a Method of Action,” in The Work of Charles and Ray Eames, 33. ↩

- See Richard Wright, The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference (New York: World Publishing, 1956) 12. ↩

- Sukarno quoted in Vijay Prashad, The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (New York and London: New Press, 2007), 34. ↩

- See Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art (London and Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983); and Irving Sandler, “Abstract Expressionism and the Cold War,” Art in America, June–July 2008, 65–74. For an alternative perspective, see John Clark, “Art Goes Non-Aligned,” Art AsiaPacific 2, no. 4 (1995). ↩

- Okwui Enwezor, introduction, The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994, ed. Enwezor (Munich, London, New York: Prestel, 2001), 15 and 16. ↩

- See Richard Davis, Lives of Indian Images (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997). ↩

- See Geeta Kapur, When Was Modernism: Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India (New Delhi: Tulika, 2000), 201–32. ↩

- See Satyajit Ray, My Years with Apu (London: Faber and Faber, 1997). ↩

- See Bijoya Ray, preface, ibid. ↩

- Moinak Biswas, “Introduction: Critical Returns,” in Apu and After: Re-visiting Ray’s Cinema, ed. Biswas (London, New York, and Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2006), 1; see also Ashish Rajadhyaksha, “Satyajit Ray, Ray’s Films and the Ray-movie,” Journal of Arts and Ideas 23–24 (January 1993). ↩

- “Pather Panchali,” in Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema , ed. Ashish Rajadhyaksha and Paul Willemen (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999), 343. ↩

- James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988). ↩

- See Kristy Phillips, “Grace McCann Morley and the National Museum of India,” in No Touching, Spitting, Praying: Modalities of the Museum in Modern South Asia, ed. Saloni Mathur and Kavita Singh (New Delhi: Routledge India, forthcoming 2012). ↩

- Jawaharlal Nehru, “Tryst with Destiny,” in Penguin Book of Twentieth Century Speeches, ed. Brian McArthur (London: Penguin Viking, 1992), 234–37. ↩

- Partha Chatterjee, Nationalist Thought in the Colonial World: A Derivative Discourse (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986). ↩

- Nehru quoted in Vikramaditya Prakash, 10; see also Gyan Prakash, Another Reason: Science and the Imagination of Modern India (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999). ↩

- Saloni Mathur, India by Design: Colonial History and Cultural Display (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007). ↩

- See Chatterjee; also Rebecca Brown, Gandhi’s Spinning Wheel and the Making of India (London: Routledge, 2010); and Lisa Trivedi, Clothing Gandhi’s Nation: Homespun and Modern India (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007). ↩

- Nehru quoted in Vikramaditya Prakash, 10. ↩

- For example, Ashoke Chatterjee, “Design in Developing Societies: Problems of Relevance,” Address to the Tenth International Congress of the International Council of Societies on Industrial Design, Dublin, Ireland, September 20, 1977. Eames Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Box 46, Folder 2. ↩

- James Belluardo, “The Architecture of Kavinde, Doshi, and Correa in Social and Political Context,” and Kenneth Frampton, “South Asian Architecture: In Search of a Future Origin,” in An Architecture of Independence: The Making of Modern South Asia, ed. Kazi Khaleed Ashraf and Belluardo (New York: Architectural League of New York, 1998), 14 and 10; and Kapur, When Was Modernism, 202. ↩

- Kapur, “When Was Modernism in Indian Art?,” in When Was Modernism, 297–324 (my emphasis). ↩

- Ray Eames quoted in Reena Pinto, “East Meets West (Interview with Ray Eames),” Inside Outside: The Indian Design Magazine, February–March 1988. Eames Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Box 46, Folder 3. ↩

- Charles and Ray Eames, The India Report, 1958, rep. Marg 20, no. 3 (June 1967): 22–23. ↩

- Ashoke Chatterjee, “Design in India: The Experience of Transition,” Design Issues 21, no. 4 (Autumn 2005): 5. ↩

- Charles and Ray Eames, The India Report, 22–28. ↩

- Pupul Jayakar quoted in Eames Demetrios, An Eames Primer (New York: Universe, 2001), 29. ↩

- Charles and Ray Eames, The India Report, 25. ↩

- Ray Eames in Pinto interview, n.p. ↩

- See Demetrios, 32, and Albrecht, 35–36. ↩

- Charles and Ray Eames, The India Report, 26. ↩

- See Ashoke Chatterjee, 5; and Singanapalli Balaram, “Design Pedagogy in India: A Perspective,” Design Issues 21, no. 4 (Autumn 2005): 15. ↩

- Ray Eames quoted in Kirkham, Charles and Ray Eames, 284. ↩

- Deborah Sussman quoted in “Appreciations,” in The Work of Charles and Ray Eames, 184. ↩

- Pupul Jayakar, Indira Gandhi: An Intimate Biography (New York: Pantheon, 1988), 122. ↩

- Ibid., 123. ↩

- See Emma Tarlow, Unsettling Memories: Narratives of India’s Emergency (Delhi: Permanent Black, 2003). ↩

- Charles Eames, personal note, January, 1972, Eames Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Box 45, Folder 2. ↩

- Jayakar, 184. The Eames chair remains on display in her house, now the Indira Gandhi Memorial Museum in Delhi. ↩

- Indira Gandhi quoted in Tarlow, 25. ↩

- Report from J. S. Sandhu to Charles Eames, September 16, 1970, Eames Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC,. Box 44, Folder 3: 1, 3 13. ↩

- See Lipstadt, 167. ↩

- Charles Eames, letter to Pupul Jayakar, February 16, 1972, Eames Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Box 45, Folder 2: 2. ↩

- See Brian Wallis, “Selling Nations: International Exhibitions and Cultural Diplomacy,” in Museum Culture, ed. Dan Sherman and Irit Rogoff (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994). ↩

- See Pupul Jayakar, foreword, Festival of India in the United States, 1985–86 (New York: Harry Abrams, 1985), 14. ↩

- Tushar Bhatt, “A Working Philosopher of Things Passes Away” (obituary), September 30, 1978, Eames Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC,. Box 44, Folder 5. ↩

- See Guilbault. ↩

- Government of India Press Information Bureau, “National Design Policy,” press release, February 8, 2007, available online at http://pib.nic.in/release/release.asp?relid=24647. ↩

- Niti Bhan, “A Competitive Nation, by Design,” BusinessWeek, December 27, 2005. ↩

- See Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class, and How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life (New York: Basic Books, 2002); Cities and the Creative Class (New York: Routledge, 2004); and The Flight of the Creative Class: The New Global Competition for Talent (New York: Harper Collins, 2005). ↩

- See Ashoke Chatterjee, 2005. ↩

- Foster, 18. ↩

- Ibid., 17, 19, and 42 (italics in original). ↩