Time is passing quickly; as I write this, I realize that I am more than halfway through my tenure as editor-in-chief of Art Journal. I’d like to welcome the new editor designate, Lane Relyea, who brings a wealth of experience in working with magazines, a deep engagement with contemporary art, and a brilliant critical voice. I’d also like to welcome two exciting additions to the editorial board of Art Journal: Saloni Mathur, a specialist in Southeast Asian art from UCLA, and Doryun Chong, an associate curator of contemporary art at MoMA.

In this issue we continue to mark CAA’s Centennial, with an essay by Nora A. Taylor on contemporary art in Southeast Asia. I am grateful for her work in writing an overview that not only synthesizes a vast array of material but locates specific geographic and individual positions in her field. Commissioning these essays has been instructive with regard to the disciplines of modern and contemporary art history: it is remarkably difficult to find scholars willing to do this important work outside the context of a high-profile conference or a paid contribution to a museum catalogue or anthology. I welcome proposals, particularly from mid-career scholars, for essays that provide a critical, and even polemical, window onto their fields.

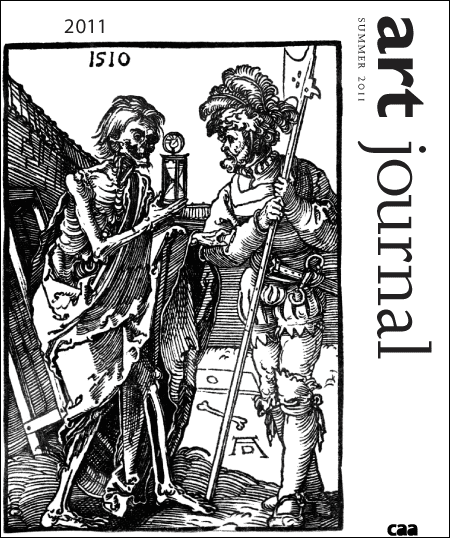

Or maybe everyone’s simply too busy. One of the two clusters in this issue, “Free Time,” is a collection of artists’ projects addressing the precious and volatile nature of “being” without express purpose. Joe Scanlan lays out the problems and pressing nature of this experience in a changed world of work; ending with Bartleby and Baudelaire suggests something more intimate and desperate. Pierre Huyghe’s film The Host and the Cloud, which he discusses with Scanlan, conveys something of that desperation, with its intersection of familiar holiday rituals and attempts at self-liberation. As Carol Bove writes, “The passage of your days is equivalent to mortality. Deinstrumentalizing time—freeing it—is a necessary step in taking possession of life . . .” Mary Heilmann’s painting Save the Last Dance for Me and Dexter Sinister’s cover image, a skeleton brandishing an hourglass, also raise the specter of death. Dexter Sinister interfered as well with this issue’s date stamp, reminding us of the peculiar nature of time lost for a journal of contemporary art, the imperative and impossibility of “now” haunting our production.

A second cluster, on politically engaged art, arose coincidentally, a coincidence that points to the currency of activist art. Marc James Léger addresses the present-day Montreal artists ATSA, and Rebecca Zorach tells the story of the 1960s–1970s Chicago project Art & Soul. Both are well aware of the potential pitfalls of political art; their accounts are critical, and the more compelling for it. The politics of not only making art but turning contemporary art into history drives the fraught and personally invested chronicle authored by members of the Guerrilla Girls BroadBand, sensitively contextualized in a separate essay by the scholar Anna C. Chave. Their story reminds us that history is made by people, and that we can make it expansive and conflicted rather than singular and official.

Is it possible to write histories that free time rather than fixing it?