At my first meeting as editor-in-chief, the Art Journal Editorial Board learned that due to fallout from the financial crisis of 2008–9, CAA could not afford to publish the journal as a quarterly—there would only be three issues in 2010, with reduced color and page count. It turns out that printing a magazine is, as these things go, a luxury. The other thing I learned at that meeting was that, like most magazines, academic and otherwise, Art Journal would likely, on some amorphous day in the future, become an entirely digital publication. This was deeply shocking—a form that I had long taken for granted, even found a little boring, suddenly in its jeopardy felt necessary, exciting, rife with untapped potential.

The next year finances stabilized, and the fourth print issue was restored. The new website was launched, and rather than obviating the paper object, increasingly it underlines and expands the content of the print magazine (all with the help of generous funding from the Warhol Foundation). Still, these conditions won’t go away, and they are hardly confined to Art Journal: they are transforming book publishing, art writing, how scholars do research, and the ways that artists make and distribute their art. The implications are endless in their detail and number, and, taken collectively, Gutenberg-like in their breadth—too much to cover in a single volume. Still, I wanted to dedicate an issue of Art Journal to scholars and artists thinking about and working with print.

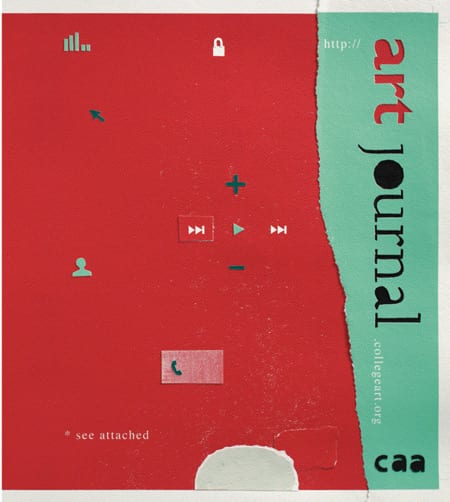

This issue is dedicated as well to taking advantage of the physical conditions of the magazine, while we have it—I hope that you can detect the difference our new printer is making in the quality of the imagery. Whenever a medium threatens to become obsolescent, its formerly invisible materiality, well, materializes. Working with our designer, Katy Homans, the artists Richard Tuttle and Matthew Brannon both pay deep attention to the thickness of paper, how to render its surface qualities and full three-dimensionality, even in reproduction. Their works on paper, with paper, are made in full consciousness of changes already effected by digital technology, but somehow retain a spirit of inquiry into what print can do, rather than anxiety over its threatened loss.

What “print” is shouldn’t be taken for granted: Michael Leja opens the imbrication of photography and the printed reproduction in an essay that extends beyond the usual Art Journal historical purview, back into the nineteenth century. Sarah Suzuki beautifully comprehends the daunting task of surveying the myriad ways artists use the print today. Harper Montgomery brings to light an instance of print’s political dimension, its innate potential to be produced by and distributed to broad constituencies. I asked the editors of Triple Canopy, the digital humanities publication, to reflect on the shift from page to screen that they both embody and trouble. Finally, expanding (and perhaps transgressing) the boundary of the print, Bruce Hainley’s essay on Sturtevant offers a profoundly rich consideration of what it means to make and to copy.