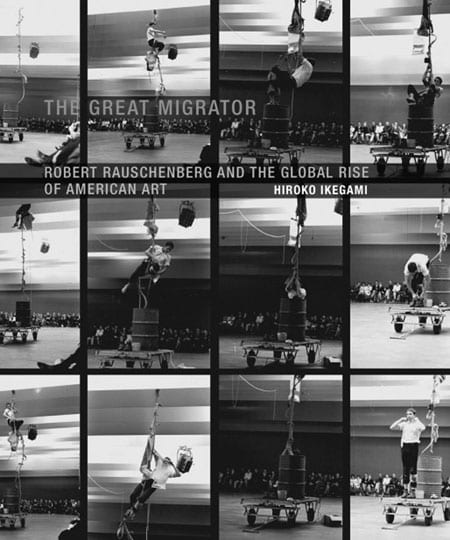

Hiroko Ikegami. The Great Migrator: Robert Rauschenberg and the Global Rise of American Art. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010. 288 pp., 87 color ills. $29.95

Hiroko Ikegami’s The Great Migrator, which toward the end quotes Homi Bhabha on the subjects of postcolonial mimicry and hybridization, is itself something of a hybrid: part traditional monograph, part Foucauldian genealogy of contemporary art in the age of globalization.1 On the one hand, the book’s focus is largely restricted to a specific time in the career of a single American artist: June to November 1964, when Robert Rauschenberg accompanied Merce Cunningham’s dance company on its world tour of Europe and Asia as costume and set designer. On the other hand, the events of this period include what could be considered almost a “primal scene” in the history of contemporary art’s globalization: Rauschenberg’s Grand Prize at the 1964 Venice Biennale, the first time this honor was accorded to an American artist. Like any primal scene, this one was simultaneously traumatic, insofar as it was largely unanticipated and unsought, even in the United States (Rauschenberg’s first major exhibition in his own country had been organized only the year before, at the Jewish Museum in New York), and at the same time overdetermined, insofar as it was facilitated by a constellation of personal and collective investments and antagonisms that changed depending on the local context. The author isolates four of these contexts, each one a city visited by Rauschenberg in the course of the company’s tour: Paris, Stockholm, Tokyo, and Venice itself. The book is structured around this sequence, with the chapter on Venice constituting its narrative and thematic center. The company’s engagement in Paris, for instance, chronologically preceded Rauschenberg’s Grand Prize, but Ikegami gives the favorable Parisian reception of his May 1964 Sonnabend Gallery show a mainly retroactive significance by showing how it contrasted with the vicious response of the French art press to the artist’s Biennale victory one month later. (These criticisms would establish something of a trend both in the United States and abroad, in which Rauschenberg’s international triumph came to be viewed as a by-product of American cultural imperialism and commercialization.) Tokyo was the last stop of the company’s tour, several months after the group’s departure from Venice, but Ikegami demonstrates that Rauschenberg’s activities there and his engagement with the Tokyo artistic community were strongly (and negatively) conditioned by his estrangement from John Cage and Cunningham—a rupture that has generally been attributed to resentment over the publicity associated with Rauschenberg’s Grand Prize, which sometimes threatened to turn Cunningham’s tour into a mere sideshow.

On one level, then, The Great Migrator can be read as a relatively straightforward history of Rauschenberg’s international reception in these four countries before, during, and after the 1964 Venice Biennale. From this perspective, the “meaning” of a work is identical to the sum total of the meanings it has held for particular viewers in various contexts: Ikegami makes no effort to interpret Rauschenberg’s work in light of any “deep structure” rooted either in the artist’s psychology and sociology or in the formal operations of his collage technique. At the same time, however, and in spite of the author’s avoidance of psychoanalytic models of explanation, this self-contained narrative is repeatedly punctuated by something like an intrusion of the real in the form of globalization’s traumatic or inassimilable aspects—from the “uncanny and disquieting” allegories of contemporary American life that European critics discovered in the Dante drawings (88), to the Icarian iconography of rise and fall that Ikegami, following Thomas Crow, distills from Rauschenberg’s Combines (117), to the collective trauma of the Vietnam War, for which Rauschenberg’s 1959 Monogram, the most iconic (and iconically American) artwork in Moderna Museet’s collection, was literally “scapegoated” by Swedish critics in the early 1970s (10).

Thanks to her exhaustive research, Ikegami has gone beyond previous studies in untangling the byzantine complexity of the cultural and bureaucratic politics surrounding Rauschenberg’s Biennale victory. Rauschenberg’s unprecedented achievement as the first American to win the Grand Prize marked a watershed not only in his own career, but in the international balance of power in the art world, as most observers instantly recognized. Many people have wanted to take at credit for the award: Leo Castelli, for instance, clearly relished being cast in the role of Rauschenberg’s Svengali, even as he denied cutting any back-room deals to secure the prize for “his” artist. But in fact, as Ikegami clearly shows, only the personal commitment of the US commissioner to the festival, Alan Solomon, could have prevailed in the face of a dysfunctional Biennale bureaucracy and pervasive American indifference. This is perhaps the most surprising aspect of the entire story: American art institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art, did nothing to support Solomon’s efforts in Venice, while afterward American critics parroted uncorroborated French allegations of shady dealings on the part of the American “team”; meanwhile the US State Department, nominally sponsor of American participation in the Biennale, initially resisted Solomon’s request to borrow the US Consulate in Venice for much-needed additional exhibition space and subsequently refused outright to fund an additional engagement of Cunningham’s dance company in that city (a performance, we learn, that played a key role in winning over the holdouts on the Biennale jury, after Solomon went ahead and arranged it anyway).

In fact, as Ikegami shows, competition between Italy and France (which had long dominated the Biennale field in winning awards) played a far more significant role in the outcome than any clandestine negotiations between Solomon and Castelli and the Italian jurors. Giving the award to an American artist was an effective strategy for unseating French hegemony in the arts and thereby shifting the balance of cultural power in Europe. This motive is similar to the one Ikegami ascribes to Pontus Hultén, who as director of Moderna Museet in Stockholm conceived the idea of forging an alliance with the New York art world in order to dispel Sweden’s “provincial” reputation and redress its continuing marginalization within Europe. Ikegami’s account also suggests that something like a generational divide played a significant role, as younger European artists were inspired to join forces with the new American art against the conservatism of the artistic establishment in their home countries. Here the author’s careful research supports her criticisms of the argument that postwar American art owed its international success to “cultural imperialism” or a covert government agenda. While the US State Department certainly recognized the propaganda value of American art’s newfound preeminence, more often than not such recognition came only after the fact.

Indeed, the research that went into this book is impressive, not merely by the standards of traditional scholarship (the author conducted interviews with key witnesses on the scene in all four cities featured in her book, and has carefully sifted through archives in the United States, Japan, and Sweden), but also in its geographic and linguistic scope. The book presents a considerable amount of information that will be new to most American and European scholars, much of it contained in the archives of the Sōgetsu Foundation in Tokyo and Moderna Museet in Stockholm; at the same time, the author has also located a number of important and heretofore overlooked documents in American sources. First and foremost, then, The Great Migrator must be reckoned a great feat of translation, and not only in the traditional sense. In addition to making available in English a great deal of historical information previously accessible only in French, Italian, Swedish, and Japanese, the author has retranslated many elements of the story already familiar to an American audience by presenting them from the vantage points of the non-American art communities that actively participated in what the author calls the “global rise of American art”—a historical development that cannot be reduced to a simple process of Americanization or a unilateral displacement of Paris by New York as the center of the international art world. The author’s introduction explicitly positions her work as a response to the call for a global art history that acknowledges the agency and self-awareness of actors and institutions on the peripheries of international modernism, rather than attributing the hegemony of postwar American art to the naive susceptibility of international art audiences to Cold War propaganda—by now a much-rehearsed critique of American paternalism whose assumptions are themselves highly paternalistic.

One obvious question remains, however: why Rauschenberg? What was there in Rauschenberg’s art (as opposed, for example, to the work of his contemporaries, including Jasper Johns), that made it such a powerful object of identification and rivalry in Paris, Venice, and Stockholm? (Tokyo, we learn, is a slightly different story: Johns, who had visited the city earlier that same year, seems to have made the better impression, perhaps because his hosts found him more receptive to the aims of Japanese “Neo Dada” and Anti-Art [Han-geijutsu].)2 It is of course impossible to answer this question without engaging in some degree of totalizing interpretation, first of Rauschenberg’s work and second of the concepts of migration and the transnational. The author’s caution in this regard is exemplary. (By contrast, this reader was strongly tempted to connect Ikegami’s insights with other influential theorizations of factors of physical, perceptual, and psychic mobility in Rauschenberg’s art, from Brian Doherty’s “vernacular glance” to Branden Joseph’s analysis of the influence of Antonin Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty on Rauschenberg’s work with dancers and choreographers.) While the book avoids offering definitive answers to such questions, Ikegami very effectively demonstrates the value of the concept of migration as a heuristic device capable of connecting the formal and iconographic content of Rauschenberg’s work with the social and institutional factors of his international success, including exhibitions, juried competitions, museum acquisitions, and reviews. At once a metaphor and a material factor of his artistic practice, migration is interpreted by Ikegami both as a unifying theme of Rauschenberg’s art and as the very medium of his international exposure. In her analysis of Rauschenberg’s activities in Venice, Stockholm, and Tokyo, the author persuasively argues that it was Rauschenberg’s mobility as an artist, and not merely the professional efforts of Sonnabend, Solomon, and Castelli, that enabled him to promote his work abroad effectively—and this not only through his personal involvement in his work’s international exhibition and sale, but also indirectly through his collaborations and interviews with young artists and critics in his host countries, many of whom did not have the resources to travel abroad to keep abreast of international developments. In this way, the author emphasizes that Rauschenberg’s interactions with local art audiences were predicated on relations of mutual interest and benefit, although an element of competition was nearly always present as well.

Perhaps the clearest example is provided by the artist’s activities in Tokyo (covered in the book’s last chapter), where he participated in “Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg,” a public event in the course of which he and his assistants produced a Combine, Gold Standard (1964), while purposefully ignoring the “twenty questions” posed to him by the audience until the handwritten list was physically thrust upon him—to be silently accepted and collaged into the evolving work. In contrast to the previous chapters’ somewhat tentative interpretations of works like the Dante drawings and the untitled 1955 Combine known as “the man with the white shoes,” where the author adheres closely to the conclusions reached by previous commentators, Ikegami delivers a highly detailed and compelling reading of Gold Standard, whose creation—on a stage, before an “interactive” audience, and in a city where Rauschenberg felt himself a tourist—encapsulates many of the issues and themes she seeks to explicate. In her discussion of the work, the author goes beyond the mere addition or mutual regulation of the methodologies of reception history and iconography to focus on the dynamics of communication and intersubjectivity in which the artist is always already implicated by his or her identification with various communities, professional, national, or even transnational. Far from representing a new “relational” or “post-Cagean” trend in the historical development of contemporary art, this intersubjectivity corresponds, as Hegel, Nietzsche, and Jacques Lacan never ceased to remind us, to that fundamental negativity which, in making recognition by the Other the prerequisite of subjectivity, sets in motion the dialectic of rivalry, aggression, and desire—i.e., history as such.

For Rauschenberg in Japan in 1964, this negativity consisted not simply in the difficulties of cross-cultural communication between American and Japanese artists or critics, but more profoundly, as Ikegami shows, in the way these difficulties were conditioned by his personal and artistic differences with Cunningham and his partner, Cage. During the course of an interview with Yoshiaki Tōno, the cosmopolitan young critic who assisted with Rauschenberg’s visit and organized the “Twenty Questions” event, Rauschenberg expressed his doubts about the very possibility of meaningful communication: “Maybe there is a trap in that idea, a trap that you somehow assume you will be understood after all. I do wonder if communication should make such coherent sense.”3 Also during his stay, he produced a collage based on a postcard-style aerial view of Tokyo titled For John Cage that incorporated numerous Japanese phrases cut out of a tourist’s phrase book, inserting among them the Japanese phrase Fugen jikkō, which Ikegami identifies with the English expression, “Actions speak louder than words” (169). (This sentiment was corroborated when, after arriving late, Cage and Cunningham ditched “Twenty Questions” partway through the four-hour event.) Since the case for Cage as a key interlocutor of the artist’s work has been so compellingly argued by Branden Joseph and Jonathan D. Katz, among others, one wonders if the author could have examined this nexus of intersubjective and intercultural “silences” a little more closely. Were the artistic differences in question solely related to Rauschenberg’s involvement with Cunningham’s company, or did they touch on a fundamental divergence in aesthetic principles? Given that Cage was the primary conduit through which the younger generation of American avant-garde artists and composers were exposed to the idea of a link between Zen spirituality and Neo-Dada aesthetics, Rauschenberg’s break with Cage would seem to take on a specifically local significance; meanwhile, skepticism about the communicative function of art had formed an essential component of Cage’s artistic philosophy ever since he renounced Schoenbergian expressionism in the mid-1940s. Finally, the rupture in his relationship with Cunningham and Cage seems to have accompanied a period of increased self-doubt regarding the distinction between creative expression and self-promotion, which may partly account for some of the artist’s difficulties in Tokyo. Ikegami suggests for instance that in the Japanese context, the famed “openness” of Rauschenberg’s work could sometimes appear as a kind of neocolonial appropriation, as in his proposal to make the front page of an issue of the newspaper Yomiuri shinbun into an “original” Rauschenberg. Meanwhile, in “Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg,” his improvisatory collage method was spectacularized in a way that recalled Georges Mathieu’s infamous kimono-clad performance painting Toyotomi Hideyoshi on the rooftop of an Osaka department store seven years earlier—even as Rauschenberg sought to neutralize this aspect of his performance by consciously referencing or redoubling it through the installation of a small television onstage that was kept on throughout the event.

A curious artifact of The Great Migrator’s hybrid construction is the emphasis devoted to the exploits of single individuals, many of them men, in a work that seeks to trace the origins and development of collective processes of globalization and the formation of new communal or “cosmopolitical” identities. In the Stockholm chapter, for example, we hear much more about Hultén than about the activities of the experimental music and intermedia workshop Fylkingen, while the Tokyo chapter focuses in depth on the admittedly fascinating story of Ushio Shinohara’s “Imitation Art” but gives relatively few details about the Sōgetsu Art Center, which did so much to foster contemporary art in Japan. At first it seems paradoxical that the “great man” model of history should be revived in a work that seeks to challenge the normative model of national art histories, given the traditional interdependence of the monograph and the historical classification of artists by national “style” or “school.” But perhaps a case can be made for extending this model of explanation to actors whom the textbooks have traditionally denied a role on the stage of world history because of geography or nationality (as with the relatively marginalized Sweden and Japan). One could quibble that the contributions of critics like Tōno merit more extended consideration, and that works like Niki de Saint-Phalle’s Tir or “shoot” performances are scanted by comparison to the attention devoted to Shinohara’s activities.4 Likewise, it is certain that contemporary art historians will want to learn more about the important role played by organizations like Fylkingen and Sōgetsu in the global dissemination of the American neo-avant-garde. But it is equally certain that this book will serve as a spur to those of us who have a stake in this history to pursue our own investigations of the historical and theoretical issues it has raised, together with the countless other complex and fascinating questions posed by the project, more urgent now than ever, of globalizing art history.

Seth McCormick is assistant professor in art history at Western Carolina University. With Reiko Tomii, he coorganized the roundtable discussion “Exhibition as Proposition: Responding Critically to The Third Mind,” published in the Fall 2009 issue of Art Journal. He is a contributor to and coeditor of the collection Communities of Sense: Rethinking Aesthetics and Politics (Duke University Press, 2009). Currently he is working on a manuscript tentatively titled “Un-American Activities: Rauschenberg, Johns, and the Borders of Visibility.”

- Or of contemporary art, period, insofar as this category is directly identified with the globalization of the avant-garde. This equation, seemingly so obvious, has been mystified by the search for a unifying theoretical model of contemporary artistic practice that could replace the now discredited concept of postmodernism: see, for example, the “Questionnaire on ‘The Contemporary’” published in October 130 in Fall 2009 (but also, by way of correction, the responses of T. J. Demos, Mark Godfrey, Vered Maimon, and Chika Okeke-Agulu to the same questionnaire). On the distinction between discursive constructions of “contemporary art” in the United States and Europe and in Japan, where avant-garde art’s relationship to “international contemporaneity” was much earlier acknowledged, see Reiko Tomii, “‘International Contemporaneity’ in the 1960s: Discoursing on Art in Japan and Beyond,” Japan Review 21 (2009): 123–47. ↩

- The title of the Japanese group is commonly rendered as “Neo Dada,” by contrast to the hyphenated “Neo-Dada” used to refer to the American movement. See “Translator’s Notes,” Review of Japanese Culture and Society (Jōsai University) 17, special issue “1960s Japan: Art Outside the Box,” ed. Reiko Tomii (December 2005): 53. ↩

- Yoshiaki Tōno, “This Work by Rauschenberg: Gold Standard,” Bijutsu techō 294 (February 1968): 66 (in Japanese), quoted in Ikegami, The Great Migrator, 188. ↩

- It bears mentioning that Tōno’s mediation of Rauschenberg’s reception was not limited to Japan. As early as September 1959, in an article on Cage, Johns, and Rauschenberg that appeared in the first issue of the Italian art journal Azimuth, Tōno had explicitly linked a Cagean aesthetics of emptiness and silence with Zen Buddhism’s critique of egoism. See my dissertation, “Jasper Johns 1954–1958: Persecution and the Art of Painting” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2007): 106–8. ↩