From Art Journal 71, no. 1 (Spring 2012)

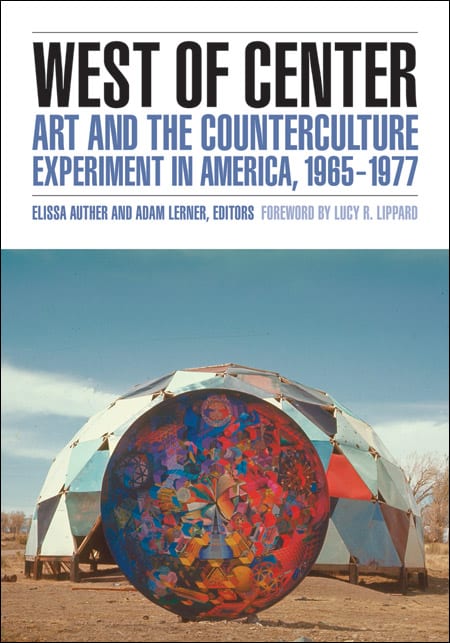

Elissa Auther and Adam Lerner, eds. West of Center: Art and the Counterculture Experiment in America, 1965–1977. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011. 448 pp., 92 color ills. $120, $39.95 paper

Chris Kraus. Video Green: Los Angeles Art and the Triumph of Nothingness. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004. 220 pp. $14.95 paper

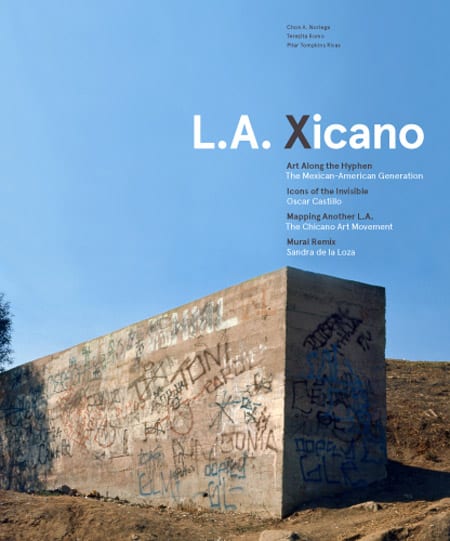

Chon A. Noriega, Terezita Romo, and Pilar Tompkins Rivas, eds. L.A. Xicano. Exh. cat. Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2011. 240 pp., 227 color ills. $39.95

Alexandra Schwartz. Ed Ruscha’s Los Angeles. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010. 336 pp., 74 b/w ills. $29.95

Cécile Whiting. Pop L.A.: Art and the City in the 1960s. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008. 272 pp., 20 color ills., 77 b/w. $45, $26.95 paper

Los Angeles mythology is hard to cut through: The city has no center, no sense of history, it has no depth. It is the city that plays itself and the city that forgets itself.

Big statements about the city’s shallowness usually come from visitors: for Fredric Jameson, the Bonaventure Hotel signals a world that is all surface, no depth; Jean Baudrillard’s Los Angeles is a simulacrum—it is “no longer real,” but then again neither are “the United States surrounding it.”1 As Amelia Jones points out in an essay on “theoretical” Los Angeles, the disorientation ascribed to the city is a displacement for the critic’s sense of displacement—the city’s diversity, its layered and quite visible history of conquest and colonization, its refusal to be legible from a New York and Eurocentric perspective have been misrecognized or misdiagnosed. The nothingness that characterizes the city as “postmodern” is itself symptomatic of the speaker’s valuation of what is already there, and what is not.2 The critic’s perspective, language, and preferred codes are all less significant in a place that used to be in Mexico and was something else before then—a place said to be slipping into the Pacific. This review is centered on different attempts to navigate theoretical and historical Los Angeles.

Ed Ruscha’s Los Angeles is small, narrow, and fat—it looks and feels like a meaty city guide. Alexandra Schwartz’s portrait of an artist’s relationship with the city opens with one chapter surveying critical discourse on the Los Angeles art world and another mapping the substantial overlap between the “Venice Mafia” (as some of the Ferus Gallery artists were known), Beat culture, and the New Hollywood of the late 1960s. (The intersection of the Ferus scene and Hollywood is the focus of Hunter Drohojowska-Philp’s 2011 book Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s, and is also the subject of a chapter in Cécile Whiting’s Pop L.A.) Schwartz covers that ground well, especially for readers unfamiliar with the subject. The book’s most rewarding chapters, which follow, are also the most conflicted. These explore the intimate links between Ruscha’s work and discourse about Los Angeles, and the artist’s cultivation of his public persona as a member of the Ferus “stud” set.

Ruscha’s portraits of parking lots, apartment buildings, gasoline stations, and the length of the Sunset Strip are both about Los Angeles vernacular culture and part of it. Ruscha helped establish the city’s “look” in the critical imaginary. Schwartz catalogues diverse exchanges between Ruscha and theorists of the city, including Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, Kenneth Frampton, and Reyner Banham. Banham’s Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies remains one of the most influential statements about the city.3 Ruscha gave Banham much to work with: iconic images of the city drained of all of the magic of the iconic subject, but also an affect that supported the author’s own investment in the city’s transformation of cosmopolitanism. In an interview with the author staged for a BBC television documentary, Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles, the artist models a casual embrace of standardization that Banham wants to claim as typical of the city. Banham asks, “Is standardization a virtue?” to which Ruscha replies, “Oh yeah, definitely.” Ruscha is relaxed about the city’s lack of commitment to its own architecture. Schwartz suggests that it isn’t just Ruscha’s subject that feels Angeleno to Banham, it’s Ruscha’s disavowal of his attachment to his subject. That nonchalance mirrors what Banham understands as the city’s relationship to itself.

Schwartz squares Ruscha’s blank, depopulated canvases with the artist’s refusal of the relevance of even the most literal references of his work. Of the relationship between his work and the city, he claimed, “I could have done it anywhere” (2). For Schwartz, the artist’s persona and his work are linked by this “economy of denial,” in which his disavowal of intention or feeling either mirrors or amplifies the blank affect of the image itself. Ruscha’s “ambiguous deployment of irony” and his “ambivalent authorial position” (219) are thus defining aspects of both his persona and his work.

This recuperation of an artist’s noncommittal evasions will be familiar to students of Pop art. Andy Warhol’s assertions that he was no more than a mirror, that there is no meaning beyond the surface of his work, figure centrally in writing about the politics of his self-branding. Whether we be talking about Warhol or Damien Hirst, this cool, deadpan stance makes a certain kind of Pop art recognizable as Pop. Ed Ruscha’s Los Angeles demonstrates the difficulty of balancing out the political dimensions of this side of Pop practice. Schwartz reminds us, for example, that Peter Plagens denounced Banham as an elitist for suppressing the defining aspects of the everyday life of Angelenos as well as the city’s more difficult realities (racism, class warfare, corruption, pollution). The “guts” of the city, Plagens argued in an infamous 1972 diatribe, “Ecology of Evil,” are consistently edited from the Los Angeles pictured by Ruscha and David Hockney.4

Plagens was onto something. On some level Ruscha’s work wants nothing to do with Los Angeles. But given the degree to which the city’s official discourse about itself is structured by an “economy of denial” (in the decades in question, this includes the active erasure of its Latino population and the region’s history), Ruscha’s disavowal of the city’s “guts” is what makes his work feel most Angeleno. In its deracination, the work speaks directly to the production of Los Angeles as a concept. Even given that its deadpan presentation of empty lots and apartment buildings have become synonymous with the image of the city, Ruscha’s work is less engaged by place than it is by Los Angeles as a site of erasure.

Schwartz applies pressure to this aspect of Ruscha’s aesthetic project when she turns her attention to the gender politics of his work and its environment. The chapter “Ferus Stud” is devoted to the artist’s self-fashioning as such in gallery advertisements, photographic portraits, and interviews. Schwartz makes a plausible argument for reading masculine anxiety in the persona he cultivated for himself as an art-world personality and in a range of static works—5 Girlfriends, 1955 (1972), Pussy (1966), He Enjoys the Co. of Women (1976)—as well as in his films (in which women consistently operate as distractions from the male protagonist’s “real work”). She indicates the critical route one might take to pick apart the homosociality of this work—it would be an exaggeration, however, to say that Schwartz pursues that argument herself.

Shulamith Firestone observed that the “sexual revolution” did little more than expand the “liberated” man’s access to women, giving him license to represent his use of women as sexually progressive regardless of his commitment to a feminist politics.5 Ruscha’s work of the late 1960s and early 1970s illustrates the point neatly. Positioning himself in bed between two beautiful women for a 1967 Artforum advertisement for his gallery, or producing a row of “five girlfriends” (who may or may not have been “his”) certainly plays to both the marketing of a circle of male Ferus artists as “studs” and to the exploration of the macho possibilities of California bohemia. Schwartz wants the word “persona” to carve out some degree of critical distance for Ruscha. But sexist posturing is hardly less sexist for being recognizable as posturing. Similarly, one is hard-put to recover Colored People (1972). How is this portrait of nappy-headed cacti not high-art minstrelsy? Ruscha’s disavowal of authorial responsibility may be a part of his “roguish charm” (some version of that phrase appears across his reception history), but it is also the posture that enables the casual reproduction of racist and sexist paradigms.

Ed Ruscha’s Los Angeles actually amplified my ambivalence about the artist’s work. But better a critic address the problematic aspects of an artist’s practice than ignore them. The attention Schwartz gives to Ruscha’s social context unsettles his placid portraits of the cityscape. She helps us to feel that something has been banished from them.

Cécile Whiting’s Pop L.A.: Art and the City in the 1960s covers similar ground. Pop L.A. is both less biographical and less burdened by hagiographic pressure than is Ed Ruscha’s Los Angeles. Whiting confidently indexes the city’s special claim on discourse about postmodern aesthetics. She is also concerned with the way that this period exerts an exceptional disciplinary force in our understanding of Los Angeles art history: the 1960s saw the organization of a contemporary art market, the dissemination of influential art magazines and journals, and the emergence of still-powerful art schools. During that decade, however, one also sees the deployment of “pop vernaculars” across a range of practices, some of which are recognized as Pop art (Ruscha, Hockney, Claes Oldenburg) and some of which are not (the Watts Towers, Womanhouse). Whiting asks us to consider the benefits of thinking less about Pop art and more about the vernacular.

Whiting offers sustained readings of not only the usual suspects but also mid-century paintings of the city’s natural environment and rapidly changing cityscapes, as well as West Coast artists rarely considered in surveys of contemporary art. Her discussion of Llyn Foulkes’s Death Valley, USA (1963) carefully unpacks the artist’s citation of landscape photography (as he paints scenes that seem more photographic than painterly). Photography is positioned in the painting as a modern technology associated with pastness—painting becomes like photography not by virtue of appearing mechanical, but rather because it joins photography as a technology of remembering. The sublimity of the West is thus only implied, as a thing of the past and as “a glimpse of somewhere else.” (59).

Whiting’s individual chapters are organized spatially: the landscapes of Foulkes and Vija Celmins anchor a chapter on the natural environment as we encounter it through visual art; “Cruising Los Angeles” considers how Dennis Hopper, Ruscha, and Ed Kienholz work with urban space; “The Erotics of the Built Environment” is inspired by Hockney’s Los Angeles paintings. In her chapter on the Watts Towers, she considers the movement of that work from the truly vernacular into the monumental as it became adopted by its (ever-changing) community. A final chapter on Happenings and performance art returns to urban space, this time to consider how Allan Kaprow, Oldenburg, and Judy Chicago activate Ruscha’s streets and parking lots.

Whiting is most eloquent when she teases out the poetics of ambivalence that characterize this dialogue between art and the city. Pop L.A.’s artists are united in having “insisted on the possibilities of reinventing the self and reimagining the built environment, even while pointing to the restrictions imposed by place on such projects of renewal” (17). Terms like renewal and development, which define so much of Los Angeles life, have always sparked feelings of hope and dread. Ansel Adams might have celebrated the sublime landscape of the West, but his generation also contributed to emerging public discourse on conservation by documenting encroaching sprawl. The book’s last chapter concludes with a provocative discussion of Womanhouse. Whiting makes a good case for reading Womanhouse alongside the image of the city presented by so many artists of this generation: “Architecturally, the astonishing installations and powerful performances at Womanhouse succeeded in shifting attention from the surface of buildings to their interiors, from the new modern infrastructure of Los Angeles to its forgotten homes and rundown neighborhoods. . . . Womanhouse made the interior insistently visible in the urban landscape and introduced it into public discourse about women” (200).

This important intervention provides the book’s finale. It also indicates the direction of critical engagements with Pop as we move away from the New York–centered world of Pop art and toward the “pop vernaculars” of cities like Los Angeles—which are only “second cities” insofar as they are also sites of colonial contest.6 Latino Los Angeles, for example, is implied in these stories almost exclusively in terms of absence. Whiting writes that “time and time again, artists of the 1960s emptied the urban landscape of bodies” (208). The panoramas of depopulated landscapes and tranquil white suburban life weakly signal the city’s histories of racial segregation and exclusion, as the denuding of the hills framing a billboard, as a standardized absence.

The antagonism between the contemporary art scene and Latino Los Angeles can be remarkably unsubtle in its expressions: the most infamous is certainly a 1972 conversation between Asco member Harry Gamboa and a LACMA curator, who told the artist that Chicanos make “folk art,” not “fine art.”7 That dismissal captures the policing of Pop quite nicely, for what is it, exactly, that made Chicano art of the 1960s and 1970s fall outside the boundaries of Pop (and most of art history)? It’s the same complex of problems that has also exiled Betye Saar from such conversations. Artists of color who were making figurative or recognizably political work were routinely diagnosed as having a sentimental, uncritical attachment to their subjects or as producing “mere” propaganda. Asco, of course, responded with Spray Paint LACMA, in which the collective “signed” the museum and declared the work to be “the first conceptual Chicano art to be exhibited at LACMA.”8

One recent critical project offers a vocabulary shift to neutralize the disciplinary policing that has excluded some of the most exciting art practices from art-historical view. In the introduction to the anthology which accompanies their exhibition West of Center: Art and the Counterculture Experiment in America, 1967–1977, Elissa Auther and Adam Lerner argue that contemporary art history has relied heavily on the term “avant-garde” as the primary framework for recognizing interventionist art practices. Much work from the West, however, is not in dialogue with art-historical modernism or official spaces of art. The absence of a Los Angeles museum culture throughout nearly the first three-quarters of the twentieth century affirms the practical reality observed by Auther and Lerner. This artistic vanguard is much closer to counterculture than to a historical avant-garde. It is more bohemian, in other words, than avant-garde. This much is already visible in the shape of discourse about Los Angeles art—conversation about Ferus turns into gossip about Hopper, meditations on surfing, the Beats, and so on. (This cross-pollination between art and California countercultures is the subject of Drohojowska-Philp’s Rebels in Paradise.)

Auther and Lerner describe the disciplinary chasms into which this work falls: neither “the narrative of the New York avant-garde [nor] the political histories of the 1960s” can account for it (xii). From one perspective, this kind of work doesn’t look like art. It’s costuming, craft, folk, psychedelia, propaganda. From another, the expressive culture of the West appears “apolitical.” In fact, some of this work is dismissed as a deep retreat from the political—even though from a twenty-first-century vantage point it is indeed hard to miss the utopian gender politics of the Cockettes (the San Francisco “gender-fuck” theater group that is the subject of an essay by Julia Bryan Wilson) or the expanded, anticonsumerist consciousness conjured in a Single Wing Tortoise Bird light show (discussed in amazing detail by the film scholar David James).9 These authors are exploring art on the edges of “non-art”—meaning work in a contiguous relationship with experiments in being. Many of the authors recover their subject’s context: Jennie Klein’s work with feminist art centers on the goddesses of feminist spiritualism; Suzanne Hudson drops Ansel Adams into a mineral bath at the Esalen Institute:

I am . . . insisting that the context in which to appreciate Adams’s production is neither the modern museum nor the modernist photographic discourse that so often justified it, but the ostensible “counterculture” on the other side of the country—a counterculture recurrently grasped in terms coeval with its most easily satirized iconography (of nudists, stoned musicians, etc.). (293)

For some readers, the projects indexed in West of Center will look more like cultural studies than art history. Auther and Lerner respond by arguing that insofar as it can’t accommodate counterculture, this version of contemporary art history reveals a deep regional bias: countercultural movements are “centered largely in the American West” (xxix). Although San Francisco is a capital of sorts, “The phenomenon was also rural and nomadic” (xxix). Their introduction is an important intervention in the practice of American art history. Auther and Lerner implicitly argue that the entire field suffers from an inferiority complex. In its endless celebrations of various New York schools, it devalues that which may actually have the stronger claim on a national practice of cultural engagement.

Reading West of Center I found myself wondering how anyone could have thought the term “avant-garde” described what we look for when we turn to art in Los Angeles. Which is not to say, however, that the city isn’t feverishly devoted to generating the effect of an avant-garde for itself. This is one subject of Chris Kraus’s collection Video Green: Los Angeles Art and the Triumph of Nothingness. These essays describe the author’s movement through spaces that are not entirely legible to each other: the contemporary art world, her (totally interesting) sex life, and her life as an Angeleno (and a landlord). The book’s subtitle is somewhat misleading: Video Green is not a jeremiad casting the city as a postmodern Sodom. Kraus does zero in, however, on the hollowness of a contemporary art scene that has taken the shape of a serpent eating its tail (expensive MFA programs feeding the gallery circuit; the gallery circuit feeding the MFA system’s hegemony). This feedback loop is intensified by the nature of much of the work valued by this system:

Whereas modernism believed the artist’s life held all the magic keys to reading works of art, neoconceptualism has cooled this off and corporatized it. The artist’s own biography doesn’t matter much at all. What life? The blanker the better. The life experience of the artist, if channeled into the artwork, can only impede art’s neocorporate, neoconceptualist purpose. It is the biography of the institution we want to read (21–22).

One essay, “Cast Away,” limns the difficulty of working one’s way out of this system. It was inspired by a storefront window in Kraus’s neighborhood, Westlake. The shop, she explains, was on the edge of MacArthur Park and catered to its neighborhood of immigrants, shipping the things people wanted to send home. The storefront window was papered over with photographs of people standing next to the boxes they’d received: proof of delivery for people who have no phone. Kraus is entranced by this display of networks of affiliation and attachment—she wants to claim it as art, or in relation to art. But she can’t, quite.

Thinking about this storefront recording of distance and attachment brings Kraus to tell another story. This one is of a classroom disaster that she witnessed while on the staff at one of the city’s fabled art schools. The lone Chicana in her class broke down when her work was attacked by one of her teachers as too sentimental. “‘We’re making art, not Hallmark Greeting Cards, here,’” he declared (147). “The work in question,” Kraus writes, “was a photo of the artist’s daughter who she’d left behind in Texas to attend the graduate program there.” The student went back home, “indebted and defeated” (147). Kraus suggests some of the things the student might have said in defense of herself: “She could have said her photos were a performative restaging of Walker Evans, recast in opposition to the appropriationist croppings of Levine from a feminine interiority,” and more (147, emphasis in original). Kraus is joking: The problem for that student was not only her sentimentality. It was also her sincerity.

Sincerity in the classroom is easy to shame: Guilelessness in such contexts is mistaken as a failure to gain critical distance, as if work couldn’t be both sentimental and ferocious (e.g., Frida Khalo). Although she is clearly the one “cast away” in the essay’s title, the story of the sentimental Chicana barely takes up a paragraph. “Cast Away” is not about that student, about art school, or about even art. It is about Los Angeles as a city of people thinking about someplace else. Art and its institutions are occasions for Kraus to engage the topic of what living in Los Angeles does to you (for the migrant, it separates). Kraus, who is writing as a critic, not as an art historian, does not approach art looking for a statement about what Los Angeles is. Instead, she tracks how art can be something that helps us to live in and with it.

I must have underlined half of “Cast Away.” Could there really have only been one Chicana in a Los Angeles classroom in the late 1990s? Could someone teaching an art class really have so little sense of sentimental practices in Chicana feminist art as to dismiss sentiment in and of itself, as if it were always naive and therefore bad? As a feminist scholar teaching at the University of California, Riverside (one of two Hispanic Serving Institutions in the UC system), perhaps it’s easy for me to forget: Yes, this is possible—but only at the kinds of places Kraus was teaching—the expensive art schools credited with putting L.A.’s art scene on the map. California State University campuses in Fullerton and Long Beach, for example, are far more affordable, have large MFA programs, and are also Hispanic Serving Institutions.

The row of galleries along La Cienega Boulevard was just one of the “happening” places in 1970s Los Angeles. The Chicano Art Movement was in full flower: East Los Angeles galleries and collectives were both recovering a sense of art history for themselves and also making one. L.A. Xicano, edited by Chon Noriega, Terezita Romo, and Pilar Thomas Rivas, is a companion to four exhibitions of Mexican American and Chicana/o art produced through the Pacific Standard Time project. The four exhibitions offer complementary perspectives on (East) Los Angeles Art History: Art along the Hyphen: The Mexican-American Generation at the Autry National Center of the American West honors the work of Mexican American artists working in the 1940s alongside an emergent discourse regarding Mexican American civil rights; Icons of the Invisible: Oscar Castillo, at the Fowler Museum at UCLA, surveys Castillo’s photographs of East Los Angeles life in the 1970s; Mapping Another L.A. at the Fowler Museum surveys work produced by the artist collectives that defined the Chicano Art Movement; and Mural Remix at the Los Angeles County Museum, features Sandra de la Loza “remixing” classic murals.10 The story of the last exhibition is perhaps the best place for me to conclude, for it indicates the direction of both contemporary art in Los Angeles and contemporary art history.

In an interview with Chon Noriega, de la Loza points out that in spite of the fact that murals are one of the defining features of the Los Angeles cityscape, “the Chicana/o mural is rarely mentioned or acknowledged as a legitimate art form within L.A.’s art institutions.”11 Between 1970 and 1980, Nancy Tovar took hundreds of photographs of Raza-oriented mural art. De la Loza describes Tovar’s slides as “mind-blowing” (they are now housed at UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center, which also produced L.A. Xicano). “The popular view of muralism tended to focus on figurative and narrative works with more visually identifiable ‘Chicano’ and political themes” (190). Tovar, however, tracked a much more diverse and experimental history of the mural. As an artist, de la Loza was humbled and inspired. Set the disciplinary erasure of this rich practice alongside the city’s failure to restore or conserve existing murals, its moratorium on new ones, and its multimillion dollar antigraffiti program (which erases murals by covering tags with gray paint), and you have a sense of what historians and artists are up against. De la Loza’s visual “remix” of Tovar’s archive at LACMA pulls the mural from the street into the gallery, one as an echo of the other’s history. Are the murals she cites not art because instead of engaging the museum, artists fought delusional textbooks and a racist police force? Or because they expressed love for the dead, or longing for home?

Generations of Los Angeles artists have been working through the myriad ways in which forms of cultural expression are policed—suppressed, forgotten, criminalized. Because so much of the work described in L.A. Xicano is so deeply engaged with the city and with the fight for social justice, this collection offers the best point of entry for those new to the idea of Los Angeles. One essay on artists of the 1940s and 1950s engages the relationship between modernist impulses of the period and social engagement; others survey the history of East L.A. galleries and the visions of the city produced by artist collaborations.12 The book’s illustrations reveal an art history as full of people as it is of a sense of place. In her essay on the cosmic vision of muralists, de la Loza gives us the term “the social sublime” to describe the density of this work and also the intense emotional impact it can have. The term is meant to signal the scale of the social change many of these artists sought to bring about. This work takes us “to the edge of the known and the unknown” to suggest “the possibility of another self” (61). Any of these terms might also be used to describe the city itself.

Jennifer Doyle is professor of English at the University of California, Riverside. She is coeditor of Pop Out: Queer Warhol (Duke University Press, 1996), and the author of Sex Objects: Art and the Dialectics of Desire (Minnesota University Press, 2006), and Hold It Against Me: Difficulty, Emotion, and Contemporary Art (forthcoming from Duke University Press). She lives in Los Angeles and is currently exploring what contemporary artists teach us about sport.

- Jean Baudrillard, “Simulacra and Simulations,” in Selected Writings, ed. Mark Poster (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001): 169–187, 175. See also Fredric Jameson, “Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,” New Left Review 146 (July–August 1984): 59–92. The Bonaventure Hotel, designed by John Portman, opened in 1976. ↩

- Amelia Jones, “(Post)Urban Self Image,” in Self/Image: Technology, Representation, and the Contemporary Subject (London: Routledge, 2006), 87–127. ↩

- Reyner Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (London: A. Lane, 1971). ↩

- Peter Plagens, “Los Angeles: The Ecology of Evil,” Artforum 11 (December 1972): 67–76. Francis Frascina, in Art, Politics and Dissent: Aspects of the Art Left in Sixties America (Manchester, NY: Manchester University Press, 1999; dist. St. Martin’s Press), which includes much discussion of the Los Angeles art scene, points out that Plagens’s own book about California’s art scene “is devoid of the perspectives and methodology that characterise his earlier article,” 15. Plagens’s Sunshine Muse: Contemporary Art on the West Coast (New York: Praeger, 1974), commissioned as a history of West Coast modernism, excludes any discussion of protest art and culture through which he might access this side of Los Angeles’s artistic and cultural life. ↩

- For a feminist perspective on the “stud” posture in relation to popular discourse about sexual liberation, see Shulamith Firestone, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (New York: Bantam, 1970), 142, where she writes, “The rhetoric of sexual revolution, if it brought no improvements for women, proved to have great value for men. By convincing women that the usual female games and demands were despicable, unfair, prudish, old-fashioned, puritanical, and self-destructive, a new reservoir of available females was created to expand the tight supply of goods available for traditional sexual exploitation, disarming women of even the little protection they has so painfully acquired.” ↩

- See Pop Art and Vernacular Cultures, ed. Kobena Mercer (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007). ↩

- LACMA absorbed this incident into the framing narrative of its 2008 exhibition Phantom Sightings: Art after the Chicano Movement. See, for example, curator Rita Gonzalez’s discussion of ASCO’s history in Phantom Sightings: Art after the Chicano Movement (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art and University of California Press, 2008), 115. ↩

- Harry Gamboa, Jr., “In the City of Angels, Chameleons, and Phantoms: Asco, a Case Study of Chicano Art in Urban Tones (or, Asco Was a Four-Letter Word),” in Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation, 1965–1985, ed. Richard Griswold del Castillo, Teresa McKenna, Yvonne Yarbro-Bejarano, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Wight Art Gallery, University of California, 1991), 122. ↩

- For a comprehensive discussion of key figures in experimental cinema from Los Angeles, see David James, The Most Typical Avant-Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). ↩

- Sandra de la Loza is also the author of Pocho Research Society’s Field Guide to Erased and Invisible Histories (Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2011). This book surveys the countermonumental work of the Pocho Research Society, which inserts plaques into public spaces to produce a counternarrative to the city’s official discourse about its history. ↩

- Chon Noriega, “Mural Remix: Q&A with Sandra de la Loza,” in Unframed: The LACMA Blog (November 2, 2011), online at http://lacma.wordpress.com/2011/11/02/mural-remix-qa-with-sandra-de-la-loza/ ↩

- The relationship to modernism is a large topic in post-WWII Los Angeles cultural politics. The association of modernism with Europe and the Left sometimes placed this kind of work in the crosshairs of anticommunist politics. Interestingly, in at least one instance, the scandal of a work’s modernist communism was associated with the fact that its figures were not legibly white. See the discussion of Bernard Rosenthal’s sculpture The Family (1955) in Sarah Schrank, Art and the City: Civic Imagination and Cultural Authority in Los Angeles (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 64–96. ↩