From Art Journal 71, no. 4 (Winter 2012)

Life is not an idea, but ideas are part of life. Thinking is the only way out of our enmities and miseries. Vision—seeing better and more freshly, with less habit and personal bias—awakens us to life. The point of waking up, of seeing and thinking, is not to dominate or even convince other people to see things your way; it is to live freely, and to demonstrate the possibilities for whomever might be interested. These statements may sound simplistic, airy, or pretentious, if not in Deleuze’s beautiful small book on Spinoza, then in the pages of an academic journal. Never mind. Art doesn’t have to be defined by or reduced to personal and ideological quarrels. At its best, art is one of many encounters that can awaken us to a life that is full, materialist without nihilism, consciousness-expanding without narcissism.

I chose painting as the focus for my last issue as editor of Art Journal not as an ideological or partisan statement; there is nothing more tedious or stultifying than the moralistic argument that one artistic practice, even a seemingly neglected one, is superior to others. In part, this issue’s focus on painting is simply one cluster among many over the past few years (print, Southern California, performance, ecological art, and so on), responding to current interests in the field. More specifically, since this is my last issue, I’ll confess that I wanted to end with work that conveys the availability of intensity and discovery. For me, painting has that capacity—not as an essence, but very often in practice. So many people around the world paint and draw, as professionals, amateurs, and all points in between those increasingly fraught and obsolescent poles. Painting is inexpensive, it’s readily to hand, you don’t need a big room or commercial support to do it. If the brush feels too heavy or tubes of paint too outmoded or culturally determined, there are any number of materials and tools that serve equally well. Painting can be (but needn’t be) quick and direct, a way to test something out right away—and if a painting doesn’t work out, it’s relatively low stakes to discard, and so, ideally suited to failure.

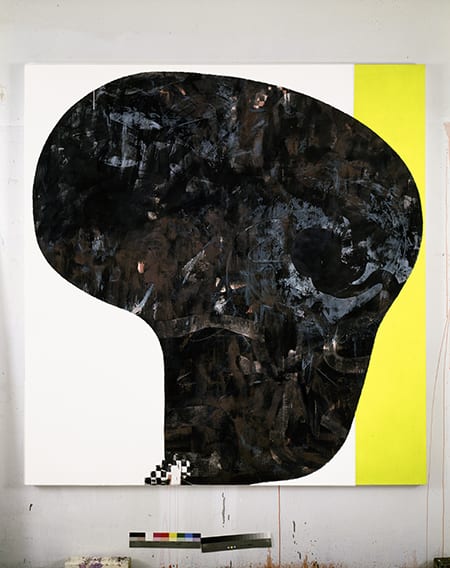

Most of all, painting puts us into the thick of things. In recent decades, the medium has often been associated with some kind of glorified self or subjectivity. I want to assert that for most artists who paint, this isn’t true, or is a gross simplification. Rather, painting always demands that we enter into a relationship with materiality—however urgent or deferred—and, in doing so, get out of ourselves. The painting process mobilizes matter: a painting is not only an object in the world, it is peculiarly animated, and often constantly fluctuates between an identity as stuff and as thing. The painting image makes the imaginary real, whether by picturing the world empathically from another point of view, or by giving form to a reality that previously existed only as virtual potential. These process/image qualities abide elsewhere, yet rarely so emphatically do they live together. Charline von Heyl’s Skull embodies contradictory coexistence; a single thing, alive (and so shadowed by death), at once an almost-too-modest exterior view of a flat, opaque surface, scratched and scarred, and, suddenly inverting scale and perspective, an infinitely expansive, mysterious interior. The painting makes no particular claims, yet seeing Skull properly could change your life.

I am so grateful for the chance to do this work over the past three years. It has been a serious and singular pleasure, and I have learned much about making a publication (print and digital) from many people, most particularly Joe Hannan, Katy Homans, and Katherine Behar; I learned a lot about handling ideas and people from the brilliant editorial board chairs Hannah Feldman and Karin Higa; Mara Hoberman was an ideal editorial assistant. The staff at the Warhol Foundation supported new initiatives, allowing us to upgrade our printing, build and test a website, and commission scholarly and artistic projects. I want to thank the writers we worked with, both those whom I pursued and solicited new work from, and the younger scholars who energetically listened, rethought, and revised their submissions for publication. And of course, I am deeply indebted to the artists who participated in Art Journal over the past three years, contributing for no real reason except their own desire to do and to engage: Kerry James Marshall, Yun-Fei Ji, Fabian Marcaccio, Paul Chan, Malik Gaines, Sharon Lockhart, Joe Scanlan, Lorraine O’Grady, Mary Heilmann, Paul Sietsema, Santiago Sierra, Sharon Hayes, Matthew Brannon, Kate Manheim, Silvia Kolbowski, David Reed, William Pope L., Josephine Halvorson, Zarina Bhimji, Richard Tuttle, Andrea Bowers, Suzanne Lacy, Dexter Sinister, Goshka Macuga, the Guerilla Girls, Amy Granat, Walid Raad, Carrie Moyer, Carol Bove, Pierre Huyghe, Ron Athey, Louise Fishman, Liz Magic Laser, Tomma Abts, and Al Ruppersberg. Whatever their individual reasons for making art, and whatever critical or curatorial position wishes to claim them, I continue to be astonished by the energy and generosity of artists.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2012 issue of Art Journal.