From Art Journal 71, no. 4 (Winter 2012)

Crisis of Containment

During the past decade a steady flow of critical writing on contemporary painting has appeared, much of it seeking to define changes to the practice that have taken place since 1990. In several often-cited essays, a shared theme has emerged in which late-twentieth-century painting is described as undergoing a crisis of containment. The perceived outcome of this development depends on one’s perspective. The medium that to this day stands as the supreme historical signifier of artistic ambition has either lost its moorings or finally achieved its full range of influence. In each scenario, painting has long since left behind a singular commitment to medium-specificity, pursuing instead a plurality of forms and references that push it to the breaking point and threaten to turn it into just one component of an all-consuming art of installation. Part of the anxiety that often marks writing on painting no doubt stems from its association with the art market and presumable willingness to serve too readily as a commodity exchanged at art fairs. Yet there is also a more optimistic outlook that sees painting as having relaxed its disciplinary boundaries to the extent that a new kind of freedom exists. In this version of events, artists can treat the medium as just one item on the art world’s equivalent of a tasting menu.

A common denominator in this critical discussion is the reliance on spatial metaphors to describe painting’s transformation. From the 2001 exhibition As Painting: Division and Displacement at the Wexner Center in Columbus to David Joselit’s 2009 essay “Painting Beside Itself,” the first decade of the new century witnessed curators and critics taking note of the medium’s increasing tendency to resist framing in time and space.1 In his essay for the As Painting catalogue, Stephen Melville writes of a “larger system” to which painting belongs, while Joselit speaks of networks constructed by contemporary painters who avoid the hermeticism of much modern art.2 In both cases, the traditionally internal considerations of painting are visibly and inextricably linked to external matters, whether concrete things (architecture or consumer products) or more abstract concepts (social relations or philosophy). It is probably no coincidence that this “spatial turn” in writing on contemporary painting coincides with the expanding literature on globalization and a widespread interest in themes of dislocation, migration, and nomadism.3 In the process, painters have abandoned long-held assumptions about their work’s minimum material requirements and rejected the urge to police the edges of the medium’s territory. Their attitude appears to be summed up by Douglas Crimp in an interview published in 2002: “I’m not sure that painting in and of itself achieves anything any longer or that there are any tasks specific to it.”4

At the same time, as Crimp acknowledges, we have to assess the impact of particular works that still maintain ties to painting’s long and embattled history. As with sculpture and photography, painting has long operated in an “expanded field” that both challenges its status as a coherent medium and creates a need, even a responsibility, to determine what of its tradition remains intact.5 Many artists are experimenting in the expanded field of painting, but the German artist Cosima von Bonin, born in 1962, stands out among her contemporaries for probing the outer limits of the practice. Having mounted her earliest exhibitions in 1990, she has been active during the very period in which questions regarding territoriality and geography took on a new sense of urgency in the visual arts, but also in the humanities and social sciences more generally, as political, economic, and cultural transformations called for new models of thinking. Though well known to German art audiences since the 1990s, von Bonin’s international reception has rapidly expanded in the wake of several major exhibitions, especially following the substantial presentation of her work at Documenta 12 in Kassel in 2007.6 Now that she firmly occupies a transnational stage, a tension that has long marked her art has become more visible, namely, the pairing of explicitly local and suggestively global frames of reference in her remarkably diverse body of work. Though one can claim that a great deal of art exhibited in large-scale group shows around the world today highlights the issue of audience accessibility, von Bonin productively complicates this binary by breaking down the divide. Even viewers familiar with her work are challenged to separate the insider references from the universal themes.

Many writers grappling with the work of von Bonin have begun by remarking on the lack of clear messages or even an unwillingness to communicate any specific content. Dirk von Lowtzow, a musician and frequent collaborator in her installations and performances, went so far as to claim, “There is nothing to understand in her work and nothing to learn from it.”7 This is quite a surprising remark to make about any artist’s endeavor. Von Lowtzow and others have commented on how von Bonin does not expect anything of the viewer, that her work “doesn’t bug you.”8 Though these statements may seem disingenuous, there is indeed an element in von Bonin’s work that favors the viewer who does not pose too many questions. One can get lost in trying to draw connections between the repeating motifs and figures (dogs, mushrooms, fences, and sailors, among several others) that occupy her installations; many of these elements are rendered in a soft fabric and present a varied cast of mostly friendly stuffed animals and objects. Whether or not von Lowtzow intended it as a serious attempt to dismiss all efforts to seek meaning in von Bonin’s work (if such a thing is actually possible), his provocation points to the problem of signification that is an important aspect of her practice. Von Bonin’s putative flight from narrative content—a trait normally associated with formalist modes of art production—is accompanied by an evident impulse to escape other forms of entrapment, especially the strictures¾both material and formal¾historically associated with particular media. I want to suggest in the following discussion that it is specifically in her two-dimensional works, sometimes hesitantly labeled “paintings,” that von Bonin sets up a powerful dynamic between containment and escape.9 To my mind, there is indeed a great deal to learn from these works about contemporary painting’s elasticity, especially in the artist’s resistance to both formalist purity and iconographic transparency.

Diagrammatic Rags

For an issue that Texte zur Kunst devoted to painting, editors Isabelle Graw and André Rottmann clarified that their aim was to “undermine the ostensible integrity of painting as a closed-off area of aesthetic activity.”10 Of course, this challenge to the medium extends back at least to the 1950s, when artists like Robert Rauschenberg began in earnest to treat painting as a hybrid practice. Since then this tendency has reappeared in different forms, from Minimalism’s “specific objects” to the painting-as-installation of the 1990s and beyond. But Graw and Rottmann are in part responding to the contemporary reassertion of painting as a singular category due to its high demand at art fairs and in galleries. A significant number of painters working today, they argue, “ignore forty years of theoretical debate” and continue to churn out pictures for the market.11 Yet, as they acknowledge, the market has also embraced the type of critically informed painting (by artists such as Michael Krebber, Rebecca H. Quaytman, and Cheyney Thompson) that both engages with and distances itself from the historical parameters of the medium. It is no longer remarkable that many of these artists often completely avoid traditional media like oil on canvas. From the use of found textiles to photographic images to digital prints, “painting” today encompasses a seemingly limitless range of surface materials and support structures. Despite the uncertainties that accompany such disciplinary expansion, both the critical debates and the market trends reinforce the sense that the stakes for maintaining painting as a distinct practice are as high as ever.

Von Bonin’s earliest work had little to do with painting. From 1989 to 1993 she produced small objects, installations, photo-based works, and a short film, much of it in collaboration with other artists living in Cologne, a city that acquired a near-mythical status for its art scene of the 1980s and 1990s. Even her first series of what definitively qualify as paintings has an air of collaboration: in 1993 she made six acrylic-on-canvas paintings of Elvis Presley based on reproductions. The distorted images immediately call to mind the raster portrait paintings of Sigmar Polke from approximately three decades earlier, creating two elements of found material, the photograph of Elvis and the painting style of Polke. Although she did not continue to make works with liquid paint on a traditional support, this series establishes an important precedent for von Bonin’s later fabric-based pictures, which she calls her Lappen (rags). The overriding impression is one of reuse, with many later works consisting of different sections of found fabric stitched together. In 1996, von Bonin sewed together seventy men’s handkerchiefs into an uneven grid formation for an untitled work that she has hung in different ways to adapt to each exhibition context. The varied patterns and slightly mismatched sizes of the individual cloths generate a two-dimensional image that hovers between order and dissolution. One can read it as an attack on high art via low materials, but the hanging arrangement, with its slightly wavy surface, evokes the intimate world of the cast-off everyday object. The fabric squares communicate on their own terms. The impulse is to look closely at the handkerchiefs and compare them on the basis of design, texture, and color. Von Bonin lends a certain dignity to these “rags” that normally absorb life’s unwanted substances. Indeed, she presents them in a state of relative purity, as if just removed from the packaging.

Von Bonin’s elevation of the humble contributes to her long-running interest in the appealing banality of mute materials. The underlying message is that there is enough visually compelling matter in the world to obviate the need for creating something from scratch. In this view, von Bonin’s textile works, which increased in number during the late 1990s and then expanded rapidly in the 2000s, take part in the established critique of painting as an exhausted medium, one whose latter-day devoted practitioners were merely going through the motions. From an earlier generation we might recall Konrad Lueg’s Geschirrtuch (Dish Cloth) of 1967, a color screenprint of a kitchen towel. Lueg’s work at the time of his involvement with Polke and Gerhard Richter in Capitalist Realism brought the spheres of fine art and vernacular culture into jolting proximity. By creating a reproduction of the object with the precise dimensions of the original kept intact, Lueg presented the actuality of the cloth at one remove, giving it a different surface texture and reinforcing its capacity for flatness while photographically capturing its uneven shape. Von Bonin’s more direct showcasing of the towel’s thingness, its tendency to droop when hanging on a wall, kept her work more grounded in the realm of the tactile. The staggered block formation of relatively unaltered, industrially produced fabric segments addresses the state of painting from a slight distance, its sagging contours making a witty contribution to the long history of declarations on the medium’s depleted resources. Composed of nothing but rags, von Bonin’s “painting” connotes a tired tradition that nevertheless imparts a sense of homey contentment.

Such a legible critical commentary can be found in many of von Bonin’s projects, but it is tempered by a perhaps stronger impulse to avoid conveying any overriding lessons. Not wanting to “bug” the viewer, she has developed a subtle strategy for giving the surface appearance of laziness while assembling an enormous body of work. To rely again on von Lowtzow, he advises experiencing von Bonin’s work as an act of “loafing around” in which no commitments are made and the artist shirks responsibility for the implications of her objects.12 Such an interpretation appeared to be confirmed in her 2010 exhibition at the Kunsthaus Bregenz in Austria with the telling title The Fatigue Empire. Here, three sub-empires (“The Oswald Empire,” “The Kippie Empire,” and “The Hippie Empire”), each a distinct and self-contained installation, occupied a floor in the museum and attested to her compulsion to give names (including recognizable ones like that of her friend Martin Kippenberger) to arrangements, as if lending them a sense of purpose that is not apparent at first glance.13 Von Bonin’s complex, multidisciplinary practice was on full view in Bregenz, signaled by her deployment of a vast range of materials: animals made from stuffed fabric, a pickup truck, sound equipment, T-shirts, photocopies, that is, more than one can easily describe without resorting to tedious listmaking. This empire of things can inspire fatigue in the viewer and, it would seem, in the artist herself. The oversized stuffed rabbits lying around on several pedestals had the word “sloth” emblazoned on their feet, yet the impressive number of large-scale installations (all of them with a multitude of distinct elements) she has produced since 2000 demonstrates that “loafing around” is a privilege she grants neither herself nor the audience.14 In moving from one set of objects to the next (there were fifty-five new works in The Fatigue Empire), the attentive viewer has no choice but to invest time and energy in an encounter with von Bonin’s work.

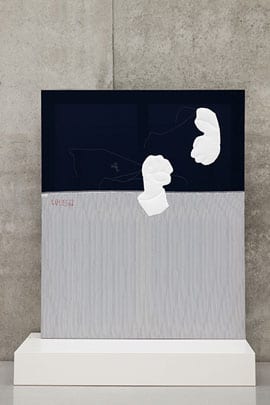

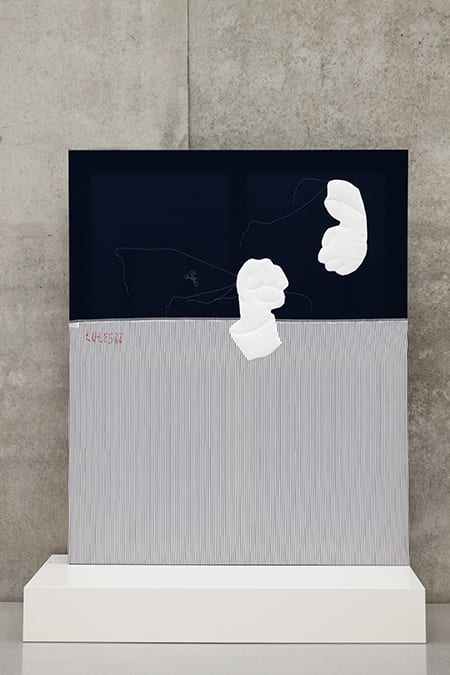

Numerous interpretive trails open up when pondering the links between all of these ambiguous objects. In looking for a sense of direction, a logical place in The Fatigue Empire was on the lowest floor, where “The Hippie Empire” presented a series of partition walls and low platforms on which von Bonin’s Lappen were mounted. More Lappen hung from the gallery’s concrete walls. Several of the pictures included stitched-on, cartoonlike hands in various configurations, some pointing emphatically, others balled up in mock-threatening fists. Viewed contiguously, these two-dimensional images gave the impression of an animated conversation or a litany of commands, emphasized by the white fabric from which the hands were made to stand out dramatically against the cloth backdrops. The group assumed the look of a storyboard and suggested that the flat shapes and lines of stitching might reveal an opaque narrative structure that could guide the experience of the entire exhibition. While this may have been wishful thinking, I want to consider the notion that in her fabric paintings von Bonin establishes a ground from which many of her ideas spring. The classical impulse to draw the viewer into the picture has been replaced by a drive to use a picture as a springboard into the surrounding space of the exhibition site and, metaphorically, into the circuits of global information flow. Her layered works, built from flat sections of fabric and spindly lines of thread, offer diagrammatic clues to both the private and public sides of her multivalent practice. Although “painting” in this instance is hardly contained, the fabric works provide a support structure that has more in common with traditional aims of painterly activity than might initially seem to be the case.

Fear of the Apparatus

Between the mid-1990s and the early 2000s, von Bonin increasingly turned to found fabrics as primary components of her material inventory. She continued making handkerchief grids during those years, but also quilt-like arrangements of multiple, clashing patterns with different surface textures. Some of these interlinked bolts of plaid cotton—occasionally speckled with foreign matter such as parakeet droppings—spilled from the wall onto the floor and, beginning around 1999, deployed unframed cotton rectangles onto which she had stitched images in thread to be mounted either on the wall or suspended from horizontal poles. These works varied in size, though all of them adopted a set of dimensions that took command of the given exhibition space. Perhaps the most significant shift in this development occurred around 2000, when von Bonin started making a substantial number of fabric paintings that could be seen as detached from the installation context, though they often appeared in relation to a larger group of objects. These works moved in the direction of stand-alone pictures, challenging the perception that “painting” only occupies a minor role in her practice. In expanding this body of work, von Bonin also invited comparisons between the Lappen and paintings by artists of an older generation, especially Blinky Palermo, Polke, and Rosemarie Trockel, who pioneered the use of industrially produced fabrics in West German painting of the 1960s through the 1980s. If considered in this broader art-historical context, von Bonin’s “rags” begin to look a lot less impoverished. Indeed, an element of skill and finesse marks the design of these images, again complicating the interpretation of her working method as one of laziness or loafing. Put simply, many of the Lappen are so visually seductive and aesthetically rich that they reward close looking for its own sake rather than for the discovery of narrative content or contextual relevance.

In his essay for the Texte zur Kunst issue mentioned above, Helmut Draxler differentiates between painting as an act and painting as a discourse. Focusing on the latter category, he borrows a term from Michel Foucault and describes painting as an apparatus (dispositif) that developed between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, something modern artists attempted to overturn only to create their own myths, from “the end of painting” to “abstraction as a world language.”15 Draxler argues that modern painting’s drive to liberate itself from traditions of craftsmanship and formal restraints resulted in a split between works of art and visual culture. For him, painting as discourse might now allow us to move beyond the misguided belief in such a division: “For the ruse of painting as such might also be seen as an opportunity to undercut the specifically modern and, as such, categorical schism between art and the culture of images, not because painting would take the stage with the aspiration to effect a reconciliation but as the historical dimension of an apparatus that had been founded on forms of mediation, networking, and interrelation.”16 This state of interconnectedness is, of course, bound up with relations of power and influence, as Giorgio Agamben has clarified in his reading of Foucault’s employment of the term dispositif.17 Draxler’s theses—along with other recent essays on contemporary painting—prompt the following questions: how far does this web of power relations take us from the ground of painting, and what ultimately allows the medium to stay relevant? In considering the possible power nexus in which von Bonin’s Lappen are implicated, we might start by asking what happens when rags become elegant pictures.

For Roger and Out, her 2007 solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, which included work since 1989 and introduced her to a wider international public, von Bonin displayed a substantial number of Lappen. The range of these images demonstrated that she had moved toward a more pronounced pictorial sensibility in the previous seven years. Around 2000, von Bonin began to use stitching to render the contours of recognizable figures; by 2007 she had built up several layers of silhouettes, words, and fabric shapes to produce complex compositions. In most cases, she also gave the object a cryptic, if catchy, title that encourages viewers to seek out specific content. In an example of this transition, von Bonin’s Grobe Küche (Crude Cuisine, 2003) appends the phrase “I’d rather not” to a ground of mixed patterns in different fabrics. Flat forms vie for the viewer’s attention with stitched lines, the ends of the threads left to dangle loosely down the surface of the material. The schematic cowboy hats and silhouettes of three partially obscured human figures walking along a rustic wood fence reinforce the title’s connection to vernacular speech without clarifying either what the artist or subjects would “rather not” do or what the “crude cuisine” might entail (could the mushroom on the lower right section of check-patterned cloth have something to do with it?). Regardless of the fruitless search for meaning, the familiar, even inviting, surface quality adds to the overall impression that in the early 2000s the lowly rag was still von Bonin’s primary unit of material support, even as the individual elements had begun to cohere as an integrated composition. Indeed, the textiles, despite their predominantly dark palette, collectively evoke domestic decor and comfort.

It is partly through the consistent embrace of “warmth” that von Bonin’s Lappen connote Gemütlichkeit (coziness) rather than dirt or waste. Manfred Hermes has identified in her fabric paintings a critique of the modernist rejection of domesticity: “For von Bonin, Gemütlichkeit effects are not merely desired but virtually pivotal, since aspects of individual choice and of the ‘peculiarity’ of taste-based preferences find expression in them as well.”18 Rather than merely pit the modern proscription of the domestic against a postmodern elevation of the mundane, von Bonin caters to both sides, refusing to acknowledge a division between rational and sensual. Whereas an influential predecessor such as Polke emerged at a moment when the shock of the trivial could still register as an attack on modern orthodoxy, von Bonin’s generation takes for granted the notion that the viewer might find visual comfort in both a rag and a well-designed composition.19 Still, in later Lappen the association with household drudgery is harder to make when faced with layers of textile and thread that indicate an increasingly subtle visual imagination. In the 2010 Nothing series, shown in The Fatigue Empire, the preexisting fabric patterns cohere into cleverly arranged landscapes, with spatial recession indicated by the diagonal slope of curving gray cloth. The inclusion of a procession of empty speech bubbles, along with a stitched drawing of a reclining figure hovering lazily over the horizon, does nothing to detract from the highly refined aesthetic. These references to nothingness, to lack of commitment, are belied by the evident skill and developed sense of play that so clearly inform their making. Like Polke’s work of the 1980s and 1990s, von Bonin has honed her craft to the point where she is perhaps no longer capable of producing an inelegant picture.

Pictures without Qualities versus Quality Pictures

My attempt to read a process of evolution into the production of von Bonin’s textile paintings obviously claims her practice for the apparatus of art history. To appeal to the discourse of painting is to deny the long-term viability of the slothfulness that might keep the artist in control of her own reception. Initially described by critics as a practice tied to the self-consciously performative Cologne art scene of the 1990s, von Bonin’s hyperdriven production has made her an internationally recognized figure with an identifiable style. In the past five years, writers have commented on von Bonin’s relationship to the market, in which the characters that populate her works serve the function of branding.20 For Graw, von Bonin’s remarkable productivity both satisfies market demands and, in a gesture of critical reflection, “outperforms” the demand itself by ostensibly generating more material than the market can absorb.21 Given that a sizable portion of this excessive output takes the approximate form of paintings, a skeptic might be tempted to see nothing more than a calculated effort to multiply profits. Yet von Bonin could surely promote her brand with a more streamlined and lucid set of references. Her continuing reliance on a cast of characters that emerged from local collaboration and personal appeal prevents her work from becoming just another example of how global art circulation relies on shared codes. In von Bonin’s practice, the semantic gap between her objects and her audience calls the expanding network model into question and possibly placesa healthy limit on the range of her influence.

The crisis of containment attributed here to painting certainly applies as well to the other aspects of von Bonin’s multifaceted body of work: the sculptures, films, sets, and performances. This issue came to the fore in her most ambitious project to date, a series of four consecutive exhibitions, collectively titled The Lazy Susan Series, that brought her work to Rotterdam, Bristol, Geneva, and Cologne in rotating constellations from 2010 to 2012. As in The Fatigue Empire, the individual works were arranged into quasi-architectural configurations, with numerous tables and divider walls contributing to the sense that both artist and curator were at pains to bring order to the chaos. In Bristol, for example, a headless mannequin wearing a tartan-patterned kimono was enclosed in a cage made of wood and chicken wire.22 When observed from a certain angle, the screen created by the wire mesh also affected the view of Lappen hanging on the walls in the background. The overlapping barriers, reinforced by the dominant stripes of numerous plaid textiles, could be interpreted as indicating an almost obsessive concern with obstacles to visuality, despite the seductively visual nature of von Bonin’s later work. To find a place for this multifaceted project in the history of art one must acknowledge painting’s prominence in past critical debates that addressed the question of optical access. Casting the gaze onto and through individual works in von Bonin’s recent exhibitions, the viewer would often fall back on the two-dimensional surface of a fabric painting as the ground on which her many figures come home to rest.

The periodic critical focus on contemporary painting raises the question of whether this traditional medium is especially difficult to situate within the still relatively new global art context. Does it always provoke greater apprehension than, say, sculpture or installation? With her productive escapism, von Bonin would seem to deny that this is the case. If anything, having abandoned paint and canvas, she freed herself to treat paintings more as storyboards than as surfaces supporting the exploration of a medium’s remaining core criteria. She thus calls forth a longer tradition, running from Marcel Duchamp’s 1918 Tu m’ through Rauschenberg’s 1955 Rebus, in which artists engage the picture plane only to sully its material purity.23 Von Bonin is too hesitant, even to the point of being “irresponsible,” to aim for any kind of resolution of painting’s vexed status.24 Yet, far from expressing exhaustion, her Lappen, when seen in relation to her installations, inspire a close look at the interconnected world of objects, while suggesting that a two-dimensional surface still offers a crucial platform on which to sort things out.

Gregory H. Williams is assistant professor in the history of art and architecture at Boston University. His book, Permission to Laugh: Humor and Politics in Contemporary German Art, appeared with the University of Chicago Press in 2012. He has published widely in art periodicals, including Artforum, Texte zur Kunst, and Frieze, and contributed essays to exhibition catalogues devoted to the work of Martin Kippenberger and Rosemarie Trockel, among others.

This essay originally appeared in the Winter 2012 issue of Art Journal.

- See As Painting: Division and Displacement, ed. Philip Armstrong, Laura Lisbon, and Stephen Melville, exh. cat. (Columbus: Wexner Center for the Arts, and Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001); and David Joselit, “Painting Beside Itself,” October 130 (Fall 2009): 125–34. ↩

- Stephen Melville, “Counting/As/Painting,” in As Painting, 17. ↩

- Among the numerous recent essays and books that point toward a renewed interest in space as an organizing concept, a useful introduction can be found in The Spatial Turn: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, ed. Barney Warf and Santa Arias (London and New York: Routledge, 2009). ↩

- “There is No Final Picture: A Conversation between Philipp Kaiser and Douglas Crimp,” in Painting on the Move, ed. Bernhard Mendes Burgi and Peter Pakesch, exh. cat. (Basel: Kunstmuseum Basel and Schwabe, 2002), 179, emphasis in orig. ↩

- The classic account of the extension of medium-specificity in this sense is Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October 8 (Spring 1979): 30–44. For later applications of Krauss’s theory to painting and photography, respectively, see Gustavo Fares, “Painting in the Expanded Field,” Janus Head 7, no. 2 (2004): 477–87; and George Baker, “Photography’s Expanded Field,” October 144 (Fall 2005): 120–40. ↩

- Von Bonin’s most extensive solo exhibitions following her appearance at Documenta 12 (June 16–September 23, 2007) include Cosima von Bonin: Roger and Out (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, September 16, 2007–January 7, 2008); Cosima von Bonin: The Fatigue Empire (Kunsthaus Bregenz, July 17–October 3, 2010); and Cosima von Bonin: The Lazy Susan Series ,which traveled to Witte de With, Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam, October 10, 2010–January 9, 2011; Arnolfini, Bristol, February 19–April 25, 2011; Mamco, Geneva, June 8–September 18, 2011; and Museum Ludwig, Cologne, November 5, 2011–May 13, 2012). ↩

- Dirk von Lowtzow, “In Fluffy Storms,” Parkett 81 (2007): 32. ↩

- Von Bonin quoted in ibid., 32. ↩

- Bennett Simpson has referred to these works as “paintings without paint”; Simpson, “Make Your Own Life,” in Make Your Own Life: Artists In and Out of Cologne, ed. Simpson, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Institute of Contemporary Art, 2006), 21. ↩

- Isabelle Graw and André Rottmann, preface, Texte zur Kunst 77 (March 2010): 106. ↩

- Ibid., 107. ↩

- Von Lowtzow, 36. ↩

- In the exhibition catalogue von Bonin listed the sub-empires in all capital letters and, for the Kippenberger reference, played with the spelling to write “KIPP¥IE.” See Cosima von Bonin: The Fatigue Empire, ed. Yilmaz Dziewior, exh. cat. (Bregenz, Austria: Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2010). ↩

- In his essay for the exhibition catalogue, the curator Yilmaz Dziewior writes that the scale of von Bonin’s output “self-ironically undermines the artist’s stance of refusal.” Dziewior, “The Right to Be Lazy: Cosima von Bonin and the Fatigue Empire,” in Cosima von Bonin: The Fatigue Empire, 132. ↩

- Helmut Draxler, “Painting as Apparatus: Twelve Theses,” Texte zur Kunst 77 (March 2010): 110. ↩

- Ibid., 111, emphasis in orig. ↩

- See Giorgio Agamben, What Is an Apparatus? And Other Essays, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009). ↩

- Manfred Hermes, “Cosima’s Ladder,” in Cosima von Bonin: Roger and Out, ed. Ann Goldstein, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007), 32. ↩

- On von Bonin’s relation to Polke, see ibid., 30–32. ↩

- See especially Isabelle Graw, “The Skipper’s Loneliness: On Market Reflections, Social Contexts, Stuffed Animals, and Fashion Labels in the Work of Cosima von Bonin,” in Cosima von Bonin: Roger and Out, 36–47; and John Kelsey, “The Mollusk of Reference,” Artforum,November 2007, 336–39. ↩

- Graw, “Skipper’s Loneliness,” 46. ↩

- This arrangement had already appeared in The Fatigue Empire. ↩

- The canonical and still relevant account of this process is Leo Steinberg’s discussion of the “flatbed picture plane” in “Other Criteria,” in Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), 55–91. ↩

- On the question of “cowardliness” and lack of responsibility in von Bonin’s practice, see Diedrich Diederichsen, “Cosima von Bonin—the First Ten Years,” Parkett 81 (2007): 49. ↩