From Art Journal 72, no. 2 (Summer 2013)

This is the abridged and edited transcript of an exchange that took place at California College of the Arts, September 28, 2012, under the auspices of the series Queer Conversations on Culture and the Arts.

Tammy Rae Carland: As I remember, we met in 1995 in Portland, Oregon, through our musician girlfriends. I had just finished graduate school and had gone to New York, to the Whitney Independent Study Program, and I was about to be deployed, which is the way I think about it, to my first teaching job in the middle of Indiana. I was spending a summer in Portland with my girlfriend at the time, Kaia Wilson, who was then in the band Team Dresch, and you were traveling in the Northwest . . .

Ann Cvetkovich: . . . with my girlfriend, Gretchen Phillips, who had been in the Austin-based bands Two Nice Girls and Girls in the Nose, and who was visiting Portland and other West Coast cities (including Olympia) in order to consider whether to move there to pursue her musical career. You and I both have connections to music scenes without necessarily having been in bands, and . . .

Carland: I was, for a minute. It was in Olympia, in the late 80s; the band was called Amy Carter.

Cvetkovich: And I’ve been a go-go dancer in Gretchen’s bands, so I have also been onstage . . . with the band, as it were.1 Our academic worlds and visual art worlds overlap with music and other live performance cultures. We should definitely theorize that! It would include considering which art forms make the best friendships. But don’t make me pick. They all have their value. I am happy that the music world brought us together and allowed us to have our first conversations.

After meeting in Portland, for example, we had many good conversations at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, where I have been a worker for many years; you came as Kaia’s guest (her band The Butchies was performing), and you did some photography for your series Outpost, which documents women’s lands. The festival is a cultural space that nurtures connections between people, and it allowed us to see each other even when we weren’t living in the same town. The story of how conversations happen and how work gets made out of those conversations is important.2 It’s part of the archive that is also represented in your 2008 project called An Archive of Feelings.

Carland: Yes! You wrote a book called An Archive of Feelings, a really important book to me.3 I’ve read it several times. When I started this body of work, I kept writing and using the phrase “an archive of feelings” when I was trying to describe what I was doing, or what I was documenting or making. Eventually I just asked you if I could steal your title. And you said yes.

Cvetkovich: And I was thrilled to be stolen from in that way!

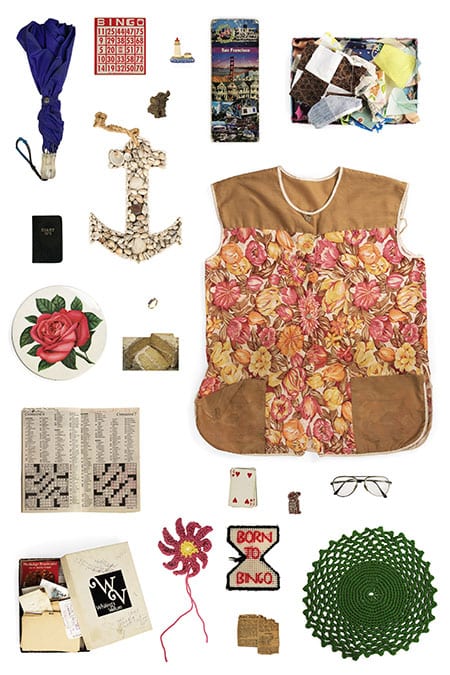

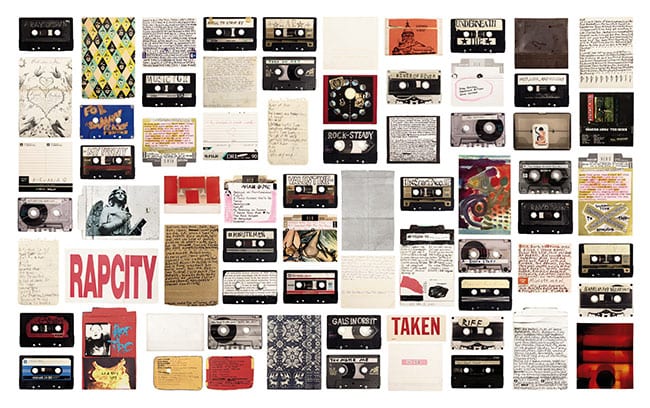

Carland: I was looking at objects a lot, and thinking about my own personal archive. The archive is something I’ve visited in my work over and over. I’ve appropriated personal belongings of other people and created biographies and narratives and what have you. This image, called My Inheritance, is literally every single thing I took from my mom’s apartment when she passed away, which filled half of a paper grocery bag. Another photograph in the series is about cassette tapes that were made for me by a boyfriend or girlfriend or a very close friend at the beginning of a friendship. I’ve kept every cassette tape, so I have something like two boxes of these; I went through them and chose tapes that summoned up a specific relationship, and I photographed them individually, then created this composite, tiled grid out of the individual images. In the final print, every object is life-sized. So that when you’re looking at My Inheritance, the apron is the size that it is in real life; the glasses are life-size; the crossword puzzle book is life-size; same thing with the cassette tapes in One Love Leads to Another. The size of the original object determines the size of the print.

What I’m doing is taking advantage of the first-handedness of objects that represent my own experience, to give value to personal experience. I’m trying to get beyond my postmodern damage—which is how I refer to the generational experience of being trained to critique the critique of the critique. Whereas the archive is about the original, the thing itself, and you get to work directly from a poignant moment, or object, or letter, or experience that you can consider to be both authentic and subjective.

Cvetkovich: I like what you’re saying about “postmodern damage.” Words like “original” and “authentic” are so loaded for us because we were taught to be suspicious of them, but the archive of feelings gives us permission to turn down the volume on the voice of critique and pay attention to the strong feelings that get attached to things.

Carland: Something that struck me in your book was that you were really looking at the historical narrative of queer trauma. I think your work looks at sites of trauma and grief and mourning as radical spaces to live in, spaces full of possibility, not spaces of shutting down and shame, but places where a person can go to claim agency. That idea is really fascinating to me. So for this body of work I photographed all these objects in my life that I felt held a kind of melancholy energy, or that were the portrait of something that was beyond me but part of me, if that makes sense.

Cvetkovich: I love that reading of my book, and I’d like to respond to it by talking about One Love Leads to Another, which is an image that I have meditated on quite a bit. In the book that came to be called An Archive of Feelings, I set out to write about trauma, but also about the ordinary feelings that are attached to what gets called trauma. The category of the archive came somewhat belatedly to that project as I thought about how we collect feelings or store them or save them. Sometimes we want to get rid of feelings of loss or sadness, but we also hang on to them, and I think that’s why we also hang on to stuff. In An Archive of Feelings I was eager to depathologize those forms of loss, or mourning, as well as the impulse to hang on to things. And I probably wanted to figure out a way to justify my own collecting tendencies.

Carland: I hear that!

Cvetkovich: My turn to the category of the archive was inspired in part by Cheryl Dunye’s autodocumentary film The Watermelon Woman (1996), and the collaborative work that she did with the photographer Zoe Leonard to create The Fae Richards Photo Archive (1993–96). That invented archive helped render visible the life of Fae Richards, the fictional woman whom the film version of Dunye tries to research. At one point Cheryl’s research takes her to the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn (in a hilarious scene in which the archive volunteers won’t give her access to their materials without the permission of the collective). Thanks to that film, as well as Not Just Passing Through, the 1994 documentary about the archives in Brooklyn by Catherine Saalfield, Polly Thistlethwaite, Dolores Pérez, and Jean Carlomusto, I found myself drawn in to the LHA and its lesbian feminist approach to history and to collecting. I was fascinated by how a bunch of lesbians had legitimated collecting stuff because, in the words of Joan Nestle, who cofounded the LHA with Deborah Edel and several others, “Anything a lesbian has ever touched is worth saving.”

I was also interested, and still am, in the epistemological and political challenges of the absent archive. What happens if the histories you want to know have left no records? What about, for example, the history of black lesbians that led Dunye to invent Fae Richards, or the minor queer figures in the shadows of Hollywood cinema or in famous times and places like 1920s Paris? What archives and historical methods are necessary to figure out who those lesbians were and what they were doing in their intimate lives?4 There are many roads that led me to the archive as a relevant category for feelings.

Carland: This is another example of the way these conversations go back and forth.

Cvetkovich: Yes—although we are using different media, we are addressing the same questions. And I wanted to talk more about your photograph called One Love Leads to Another. The mixtape, the cassette tape that a friend or lover makes for you, is a genre that’s disappearing with changes in musical formats and technologies. It’s an important medium for an archive of feelings because it provides material evidence of how friendship and the connections we make with one another—not only through making music but through passing it along—matter. It’s also meaningful to use the medium and practice of photography to archive objects that might otherwise disappear, or seem inconsequential. I’ve been writing about how your project of photographing objects becomes a form of archival practice. Your work shows how the stuff we collect, and the feelings attached to objects, can be archived by virtue of making a photograph. The photograph insists that the thing pictured matters. When you hang an image of these cassette tapes on the gallery wall, you make a statement. You say, “These personal feelings are important enough to be made public.” I love that about your Archive of Feelings project, which adds to a concept that has been tremendously generative for me.

I’ve just written an article, for an edited collection called Feeling Photography, that places your Archive of Feelings alongside Zoe Leonard’s Analogue, which includes a series of photographs of storefronts in New York City that document disappearing neighborhoods—like the Lower East Side—that have been important for queer art and artists.5 Leonard has suggested that the photographs document how losses from AIDS reconfigured the city. They speak to the problem of absent archives, by cultivating a capacity to see things that don’t seem to be there. The photographs enable us to glimpse ghostly presences. There are also hints of such presences in the glimpses of rainbows in the lesbian landscapes that you photograph in your Outpost series. Both Archive of Feelings and Analogue made me think more deeply about artists as archivists. And about how archives and feelings twist into one another. Each project, in its own way, constitutes a profound response to the ongoing challenge of representation. But for me they are also coming from this cultivation of . . .

Carland: Absence?

Cvetkovich: Yeah. I would say that the archival preoccupation, for me, comes straight out of the era of AIDS and AIDS activism. The palpability and the directness of loss are very real for my generation.

Carland: I want to thank you for bringing up the significance of being a member of the epidemic generation. That’s another thing we share. I think we both have deep concerns about and have done a lot of work around marginalized people, things, and feelings that are not deemed worthy of being “saved.”

Cvetkovich: Yes. And I want work on queer archives, and archives of queer intimacy, to help with addressing the legacies of genocide, slavery, and colonialism. The archive of feelings is not just about LGBT queerness; it’s about an attunement to racialized histories, as well as sexualized ones. The queer archive is about making connections with the deeply sedimented histories of violence and survival that form the social, political, and cultural environments we inhabit in the U.S. Unless we do radical kinds of recovery work around archives, and also grapple with profoundly absent archives—by acknowledging missing lives and missing feelings—we can’t move forward.

Tammy Rae Carland is an artist whose work primarily deals with issues of marginalization, archives, and performance. In the 1990s she produced a series of influential fanzines, including I (heart) Amy Carter, and from 1997 to 2004 she co-ran Mr. Lady Records and Videos. Carland is a professor at the California College of the Arts where she also chairs the photography program. She lives in Oakland and is represented by Silverman Gallery in San Francisco.

Ann Cvetkovich is the Ellen Clayton Garwood Centennial Professor of English and a professor of Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of Mixed Feelings: Feminism, Mass Culture, and Victorian Sensationalism (Rutgers, 1992), An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Duke, 2003), and Depression: A Public Feeling (Duke, 2012). She coedited (with Janet Staiger and Ann Reynolds) Political Emotions (Routledge, 2010), and she has been coeditor, with Annamarie Jagose, of GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies.

This conversation originally appeared in the Summer 2013 issue of Art Journal.

- For an account of that history, see “White Boots and Combat Boots: My Life as a Lesbian Go-Go Dancer,” in Dancing Desires: Choreographing Sexualities On and Off of the Stage, ed. Jane Desmond (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), 315-48. ↩

- For an account of why interviews and oral histories are important for documenting lesbian feminist art practice, see Ann Cvetkovich, “The Craft of Conversation: Oral History and Lesbian Feminist Art Practice,” in Oral History in the Visual Arts, ed. Linda Sandino and Matthew Parington (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 125-34. ↩

- Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003). ↩

- For an innovative answer to his question, see Lisa Cohen, All We Know: Three Lives (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012). ↩

- Ann Cvetkovich, “Photographing Objects as Queer Archival Practice,” in Feeling Photography, ed. Elspeth Brown and Thy Phu (Durham: Duke University Press, forthcoming in 2014.) ↩