From Art Journal 73, no. 2 (Summer 2014)

By Tamara Díaz Bringas; translated from the Spanish by Jason Weiss. The Spanish text is here.

Young Artists Take Up Baseball

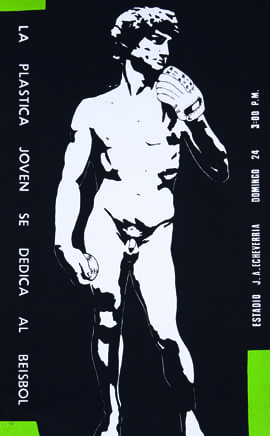

“Play ball!” the umpire would have said to start that baseball game with so many artists and not a single ballplayer. “Play ball!” the players would have heard, perhaps suspecting that the game had really begun long before that 24th of September in 1989. In the days leading up to the occasion at the Círculo Social Obrero José Antonio Echeverría [Workers’ Social Club, formerly the Vedado Tennis Club, in Havana], a call went around by way of graphics and word of mouth: “Young artists take up baseball,” it said, in a surprising wording that seemed to describe a condition rather than a specific event. It wasn’t a matter of going to a ball game that Sunday. The notice implied a public declaration: We’re taking up baseball because we can’t make art.

The project arose at the home of Abdel Hernández, where a group of artists had met to discuss recent episodes of censorship of art exhibitions and to think of possible ways to respond. One of those present, Hubert Moreno, suggested the idea of organizing a ball game, which would have the advantage of displacing the “conflict” from cultural institutions to a terrain difficult to censor. The idea was well received from the start, and put into practice as a collective and anonymous proposition.

If the game was produced as a reaction to successive events of censorship and institutional retreat, I like to think it was also possible because of the common experiences accumulated in those years by a fairly broad group of artists, critics, students, curators, and other people active in the art world. The conditions making the event possible had to do with censorship but also with the existence of a cultural network that shared concerns, debates, experiments, and critical strategies, and which by 1989 could recognize the same malaise and at least attempt a common stance. The sense of a movement that “young artists” had back then was decisive in that collective invention which the Ball Game signified.

![Nudo [Eduardo Marin y Vladimir Llaguno], cartel “La plástica joven se dedica al béisbol” / poster “Young Artists Take Up Baseball,” 1989, impreso en / printed at Taller de Serigrafía René Portocarrero, Havana (artwork © Nudo)](http://artjournal.collegeart.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Bringas2-309x500.jpg)

The Final Exhibition

That September of 1989, Flavio Garciandía presented La última exposición [The Final Exhibition], a veritable feast of hammers and sickles turned into sexual organs, orgiastic prostheses, a shameless voluptuousness of socialist symbols and modern styles. 1 “His hammers and sickles,” wrote Gerardo Mosquera that year, “allude to ‘Perestroika’ as a revitalization of socialism, but at the same time they constitute a ‘third world’ carnivalizing of the symbol in order to break its orthodoxy and make it take part humorously in the multiplicity and contradictions of the South.”2 Years later, Osvaldo Sánchez declared that “the ideological orgy seemed to contaminate the tropics. It couldn’t be more ironic, futurism and action painting to represent Cuban stagnation.”3

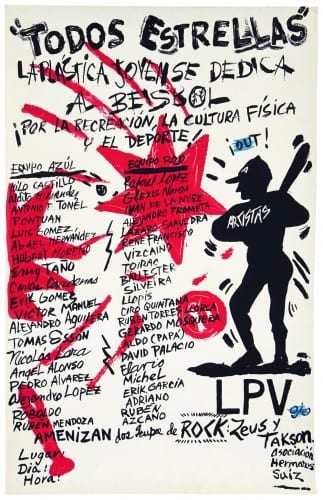

![Kattia García Fayat, Juego de pelota, 24 de septiembre de 1989 [Ball Game, September 24, 1989], black-and-white photograph (photograph © Kattia García Fayat, provided by the author). “LPV” stand for “Listos para vencer,” or “Ready to win,” a sports slogan common throughout Latin America](http://artjournal.collegeart.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Bringas3-500x351.jpg)

“LPV” stand for “Listos para vencer,” or “Ready to win,” a sports slogan common throughout Latin America

Eroticizing symbols, calling for pleasure, relaxing the severity of the socialist model—as in the works Garciandía called Tropicalia—implied a radical political gesture. Official Cuban politics, nonetheless, kept away, being rather fearful of that “revitalization” of socialism. If the Soviet model had been implemented for almost thirty years with incredible faithfulness, in the era of Perestroika the “copy” was revealed as meaningless. In April 1989, in a speech on the occasion of Mikhail Gorbachev’s visit to Havana, Fidel Castro proclaimed, “Doesn’t it seem really absurd to pretend—as do some people abroad—that we apply to a country of ten million inhabitants the formulas that must be applied in a country of 285 million inhabitants, or that for a country covering 110,000 square kilometers [42,471 square miles] we apply the formulas for building socialism that must be applied in a country that covers 22 million square kilometers 4? Anyone will understand that it’s absurd, anyone will understand that it’s crazy.”5

Four months after that visit, the order went out for the return of ten thousand Cuban students from the international socialist field, while sales of the journals Sputnik, Novedades de Moscú, and Tiempos Nuevos were prohibited. “Glasnost” had gone too far . . . all the way to the kiosks of the Caribbean, and Soviet media were beginning to publish content “not recommended” for Cuban readers. Maybe that’s why I have no memories from that time of the Tiananmen Square massacre or the fall of the Berlin Wall.

In that crucial year in our recent history, in the East and the West, young Cuban artists gathered at the Echeverría stadium, making of their little “diamond” an implicit claim for freedom of expression. That would be the last time the artists of the 1980s generation got together to be exposed.6 Though I say “expose,” it was more like staging a demonstration, putting themselves at risk, making themselves vulnerable, than the traditional idea of an art exhibition. The Ball Game would be, in this sense, the final exhibition.

Garciandía’s show took place at the Proyecto Castillo de la Fuerza, which between March and October of 1989 presented an intense schedule of the most radical artistic and political practices of that moment. One of the organizers, the artist Alexis Somoza, would state that the project “was conceived by artists and cultural institutions as a ‘glasnostic’ effort.” He added, “Such a spirit from Moscow drew attention from the global levels of the country’s leadership to its first three exhibiting teams, while the very immediacy of political decisions allowed it, until the events of June and July of 1989.”7

Melodramatic Artist

The events of June and July of 1989: the First Cause. General Arnaldo Ochoa, hero of the Cuban Revolution, and thirteen military personnel were arrested on June 12, accused of drug trafficking and other crimes. On July 7, a court-martial condemned four of the officials to death, and the rest of those charged to sentences of ten to thirty years. On July 9, the entire Council of State ratified the death penalties. On July 13, the newspaper Granma published: “The sentence by the Special Military Court against Ochoa, Martínez, Antonio de la Guardia, and Amado Padrón was carried out.” By then, the trial that took place between the detention and the sentencing had been televised for a month, with regular reenactments of the prosecutor, the disciplinary committee, the guilty plea from the accused, and the cautionary punishment.

The serious political tensions implied by the “Ochoa case” shook Cuban society like an earthquake whose aftershocks we are still not able to measure. What is certain is that something changed radically after those “events,” in the artistic context as well. As the organizer of the Castillo de la Fuerza project observed, there was a displacement at the “global levels of leadership,” in those “upper spheres,” as Garciandía would call some of his paintings.

In mid-1989, Eduardo Ponjuán and René Francisco Rodríguez presented Artista melodramático [Melodramatic Artist] at the Castillo, a polemical exhibition that opened and closed in a matter of days and was reopened with a few pieces fewer. Shortly after, the president of the National Arts Council, Marcia Leiseca, was dismissed. The image of Fidel, whose ubiquity in the Cuban context was completely normalized, turned out to be problematic in those representations: in the mirror before which a strongman shows his biceps (Reproducción prohibida), in the lighthouse that guides and illuminates (Las ideas llegan más lejos que la luz [Ideas Go Further than Light]), in a fortress window (La real fuerza del castillo [The Castle’s Real Force]). It is possible that the repeated image of the leader may have called forth one of the ghosts that scared people in times of Perestroika: the cult of personality. Perhaps that specter posed too much of a trap to allow for more complex readings of those practices with their strong parodistic dimension, in which references to the Russian avant-garde had to do with a visual repertoire and artistic experimentation, but also with a certain idea about the politicization of art.

Luis Camnitzer, in a 1991 text, as a postscript to his committed research on Cuban art of the 1980s, noted the change in his own view of the decade, from what he first perceived as an open, flourishing process in which “some obstacles” would later appear: “Russian Constructivism comes to mind as a possible precedent, a movement that wanted to be part of the Russian Revolution and eventually ended up encapsulated, both isolated and insulated, in an alien development of visual history.” He added, “The art of the Cuban artists of this last decade is too representative of Cuba itself to be in that danger.”8

Artista melodramático and the political limits which that episode made evident were the (final) detonator of La plástica joven se dedica al béisbol. In a way, this collective action imagined a reenactment of the conflict in the space of the game—with its metaphor of war—although there were no declared “adversaries” on the field. As there would not be any real “spectators” outside the performance either, since nearly all the participants, even in the stands, were there for the same gesture: to make of that playing field a theatrical stage and a political arena.

![René Francisco Rodríguez and Eduardo Ponjuán, Las ideas llegan más lejos que la luz [Ideas Go Further Than Light], 1989, óleo sobre madera / oil on wood, 20½ x 26½ in. (52.1 x 67.3 cm), exposoción / exhibition Artista melodramático, 1989 (artwork © René Francisco Rodríguez and Eduardo Ponjuán)](http://artjournal.collegeart.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Bringas5-500x394.jpg)

Suicide or Malleable

“The squeeze play (or suicide squeeze) is normally done with a runner on third base. The batter bunts, and when the ball is thrown to first base, that offers the runner on third the chance to score.” That is how the artist Rafael López-Ramos, one of the protagonists of the Ball Game, introduces his rereading of the event, arguing, “More than a stolen base, ours was a squeeze play, a bunt that allowed the next generation, already on third base, the chance to score. Yet, sacrifice is not the word that best describes our game. We were doing what we had to do, and we did what we do best . . . as long as we could.”9

The image of the squeeze play places the Ball Game between two genera-tions or at least between two quite different situations for the production and circulation of artistic practices. In stories of recent Cuban art, that action in 1989 is usually situated at the hinge where the 1980s meets the 1990s, and is understood as a moment of transition or as a drastic point of inflection that would signal a change of era. “After the Ball Game, the cynicism began. . . . That act marked a before and after in Cuban art,” said Glexis Novoa, one of the protagonists in the political and artistic experimentation in the late 1980s in Cuba.10 For her part, the curator Cristina Vives asserts, “It’s funny that the spirit of the 1980s would end metaphorically in an actual ball game. . . . It was colleagues vs. colleagues, all of them stars of that decade but convinced that their objectives-utopias had ended.”11

![Carlos R. Cárdenas, Suicida o moldeable [Suicide or Malleable], 1989, serigrafía sobre cartulina / serigraph on cardboard, 20 x 27½ in. (50.8 x 69.9 cm). Collection of Orlando Hernández (artwork © Carlos R. Cárdenas)](http://artjournal.collegeart.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Bringas6-500x364.jpg)

On the other hand, for the curator Eugenio Valdés Figueroa, “The first manifestation of the art of the 1990s occurred in 1989, when artists and critics brought about the by-now-much-discussed Ball Game . . . a fictitious act, simulating and metaphorical, like the art world had not seen the entire decade.”12 In her text “Play Off (también, a propósito de Antonia),” the critic and curator Elvia Rosa Castro says, “The Echeverría performance—which every game is—more than a morphological change, traced the advent of a rethinking of the functions, variable in access and statute, of art in the new socioeconomic-cultural context.”13

A propos of Antonia (Eiriz), the writer and curator Orlando Hernández placed the Ball Game of 1989 in relation to her 1996 La muerte en pelota [Death in Baseball, or Death Stark Naked], a piece—like others by Antonia Eiriz—considered in its time as too pessimistic for the obligatory fervor. “Significantly, both works are closely related not to the beginning of a National Series, nor to the Panamerican Games, but to the unpleasant phenomenon of censorship, that is, both were, in one way or another, the artists’ civic responses to the intolerance of official Cuban institutions regarding freedom of expression.” Hernández continues: “So that, in addition to works of art, Antonia’s large paintings and collages of the 1960s, as much as the Ball Game of 1989, should be seen and understood as two sociocultural milestones of great importance within the history of Cuban art.”14

The Blockade

On November 1, 1989, a few days before the fall of the Berlin Wall, the third Bienal of Havana was inaugurated, a key event in redefining the biennial format but above all the limits of what is “contemporary” according to that model of international exhibitions. With the theme “Tradition and Contemporaneity” and open, according to its own announcement, to the art of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Caribbean, the third Bienal valorized not only artistic practices from “peripheral” contexts, but also other cultural practices that usually circulate under the rubric of craft or popular art, like the wooden carvings dedicated to Simón Bolívar, the Mexican dolls, or the African wire toys that made up the “Nucleus 2” at that event with its clear call for decolonization.

In 2011, the publisher Afterall dedicated the second volume of its series Exhibition Histories—which aimed to reconsider some of the exhibitions that have influenced how we experience and understand art—to that third Bienal of Havana. In the central essay of Making Art Global, Rachel Weiss points out, “The third Bienal was one of the first exhibitions of contemporary art to aspire to a global reach, both in terms of content and impact, and it was the first to do so from outside of the European and North American art system, which had, until then, undertaken to decide what art had global significance.”15 In 1989, as Charles Esche reminds us in the introduction to that same volume, the World Wide Web was invented. In Cuba, at the beginning of 2014, Internet access is still restricted and controlled by the State.

![Tonel (Antonio Eligio Fernández], El bloqueo [The Blockade], 1989, instalación / installation view, III Bienal of Havana (artwork © Tonel; photograph provided by Ramón Martínez Grandal)](http://artjournal.collegeart.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Bringas7-500x256.jpg)

El bloqueo [The Blockade], the work by Tonel at the Bienal of 1989, installed in the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, was in the imaginary of so many people, a simple and powerful metaphor: a map of Cuba made with blocks of cement. Besides being an economic condition imposed on the island since 1960 by the United States, the embargo is seen as something internal, like a self-embargo. The emphatic materiality of those blocks of cement depicted an island sinking under its own weight . . . “always further down, to the point of knowing the weight of his island.”16

As if the weight of the island could fit into a (heavy) joke, Tonel’s work was exhibited under the soothing title Tradición del humor. That title, at the “Nucleus 3” of the Bienal, gathered many of the most critical proposals by Cuban artists, among them Novoa, Ciro Quintana, Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas, and Lázaro Saavedra. The attempt to mitigate the critical reach of those practices was obvious. Mosquera, one of the curators of the Bienal, would explain that “in the third edition Cuban artists with hard-hitting critical work were ghettoized in a group show called La tradición del humor, together with cartoonists, some of them official. This decision was imposed from the top as a way to divert and reduce the artists’ social and political impact in the Bienal.”17 After that third edition of the Bienal, Mosquera himself, who had been one of its founders, resigned.

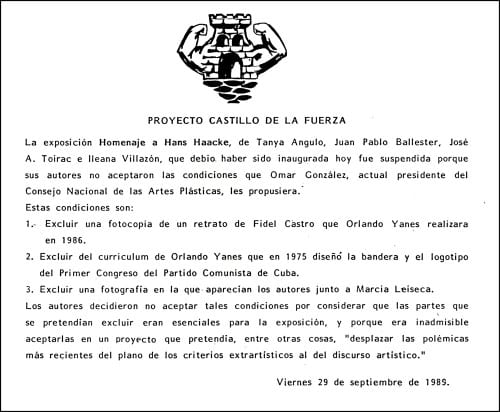

Between 1988 and 1989, the account of projects officially censored in Havana usually cites these shows: A tarro partido II [Broken Horn II], by Tomás Esson, at Galería 23 y 12; Nueve alquimistas y un ciego [Nine Alchemists and One Blind Man], organized by Arte Calle at Galería L; Artista de calidad [Artist of Quality], by Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas, at Galería Habana; the actions by the group AR-DE (Arte-derecho [Art-law]) in the park of 23 and G; and the shows Artista melodramático and Homenaje a Hans Haacke, at the Proyecto Castillo de la Fuerza. The generation of the 1980s was called the “Cuban renaissance,” without having anything at all to do with the recurring joke of Orson Welles in The Third Man: “In Italy for thirty years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but also Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love, they had five hundred years of democracy and peace—and what did they produce? The cuckoo clock.”

Ideology Detector

In elementary school I was in charge of “patriotic activities,” and it was my job to organize the morning liturgy: saluting the flag, singing the anthem, reading out the anniversaries of major events, and the declamation of some slogan. At twelve, I was still a communist “pioneer” and was sent away—like nearly all children in the provinces—to a school in the country where, between days of study and work, we also had to fit in certain slogans. I remember being recorded in vaguely rhythmic litanies devoid of any sense. In one of them we intoned, “Ideology is first of all conscience.” I didn’t really know what that phrase meant, but in the chorus it sounded like a war cry.

Maybe that’s why in Cuba during the Cold War “ideological problems” were constructed as the internal enemy to fight against, an enemy that was difficult to recognize, with so much dissimulating: it could hide, for example, in long hair or jeans, in listening to the Beatles, in intellectualism, in lacking enthusiasm or being too critical. The vague limits of what might be an “ideological problem” were put into tension in another key work of 1989, Detector de ideologías [Ideology Detector]. In the context of successive debates and censorship, Lázaro Saavedra invented this device that would supposedly allow one to measure the level of “problematicalness” in a work of art, from zero degree or “no problem,” to the extreme of “ideological diversionism,” a scale of values that has been in fact as frightening as it was arbitrary in its political application. But maybe we could read that Detector with “diversionism” as the highest value. It was everything that official rhetoric stigmatizes: the deviant, the diverse, diversion.

![Lázaro Saavedra, Detector de ideologías [Ideology Detector], 1989 (artwork © Lázaro Saavedra)](http://artjournal.collegeart.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Bringas8-500x465.jpg)

“Long live ideological diversionism!” reads a frequently worn T-shirt by Gorki Águila, leader of the punk band Porno for Ricardo. A few months ago, while the members of the band tried to give a “concert” from the balcony of their house, in response to the cancellation of a public appearance, someone cut their electricity. A similar episode occurred on September 24, 1989, when the rock groups who “livened up” the Ball Game played their first note and there was a power failure. In spite of that, the baseball game transpired in relatively normal conditions. On an adjacent field another game took place. According to the artist Rubén Torres Llorca in Novoa’s film El canto del cisne [Swan Song], the neighboring teams were made up of soldiers, who were there in case they needed to suppress something or so that their mere presence might make that unnecessary.

Like a synecdoche of the social space, on the playing field everyone was in costume. In that terrain of disguise the soldiers pretended to play softball, the artists pretended to play baseball, and the massive protest of “young artists” pretended to pass as an inoffensive ball game. After all, in a context where the right to strike was not permitted, perhaps this was only possible as transvestism. About that experience, Saavedra himself noted: “It was a type of action that goes out of the gallery and functions as a ‘strike’ demonstration (this was even the term it was given back then by the party’s ideologue, Carlos Aldana, in a meeting at the Editora Política where some of us who participated in that ball game were quoted).”18 As the political commissars of the time sensed, the action at the Echeverría announced nothing less than an agora, a public square, a true “field of dreams.”

Homage to Hans Haacke

Barely five days after the Ball Game, another episode of censorship would take place, this time at the show Homenaje a Hans Haacke, by the group then made up of Tanya Angulo, Juan Pablo Ballester, José A. Toirac, and Ileana Villazón. One of the inquiries that would turn out to be most unsettling was devoted to an official painter and the institutions that elevated him. Calling itself ABTV, after the last names of the four artists, the group produced a portrait of Orlando Yanes in the manner of the famous billboard of Ché designed by Yanes for the Interior Ministry building in the Plaza de la Revolución. The project also included a résumé of the painter since his first show in 1948, as well as copies of the portraits Yanes did of Fulgencio Batista and Fidel Castro in 1952 and 1986, respectively.

It is not surprising that Hans Haacke would be invoked in Havana by a project of institutional critique that needed to construct (and justify) its own genealogy within the art world. But it is curious that in their response to censorship, the artists cited the intention to “displace arguments from the extra-artistic plane to the plane of artistic discourse,” resorting to an assumed specificity disassociated from history, the economy, politics . . . from all that which precisely the Homenaje a Hans Haacke made visible. With certain variations, that polemic ran through numerous cultural debates in Cuba in the late 1980s and early 1990s, years in which remarkable acrobatics of discourse were necessary if one were to circumvent the limits imposed by the forces in power. But it remains paradoxical that the defense of a political practice would take refuge in a certain notion of art’s “autonomy.” The tactical use of the concept of autonomy would not be exempt from contradictions, to the extent that the supposed suppression of “extra-artistic” criteria tried as well to strip those works of their political potency. In a text on Haacke, the critic Benjamin Buchloh warns about the “intrinsically repressive functions of purely visual concepts that prohibit historical representation.”19

In a climate of systematic restrictions of political liberties, the practices of institutional critique seemed to multiply, including several that did not at first propose to question the institution or power but which ended up making their limits and contradictions visible. As the curator Osvaldo Sánchez noted in the immediate wake of those years, “Already in the late 1980s, cultural institutions did not know how to confront the opportunism of hardcore Party figures without killing the mental effervescence of those young people who were born with the Revolution. The power structure could not understand that the merciless critique was the last recourse of the very legitimacy of the Revolution as a living event.”20

Toward the end of the 1980s, the coupling of art and institution crystallized in the Cuban context as an antagonistic pair. I wonder, nonetheless, if the insistence (to this day) on speaking of that “conflict” doesn’t displace—or suppress—a much more radical disagreement. We know that the institution or its agents have little room to maneuver in a totalitarian regime, where censorship is more structural than contingent. The institutional critique brought about by these proposals—including La plástica joven se dedica al béisbol—should be understood as a questioning that spreads beyond the artistic institution to other social practices and spaces. After all, representatives of the “art institution” at that time were also in the stadium. More than institutional limits, what the Ball Game put on stage were political limits to democratic demands.

What You See Is What You See

“From December 23, 1988, until this past January 28, in several Havana galleries, the show of Cuban abstract art, Es sólo lo que ves, remained open to the public. It featured the most recent work by more than fifty artists, among them José Adriano Buergo, Ana Albertina Delgado, Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas, Tania Bruguera, Arturo Cuenca, Aldito Menéndez, Tonel, Tomás Esson, Abdel Hernández, Glexis Novoa, Segundo Planes, Ponjuán, Ciro Quintana, Lázaro Saavedra, Sandra Ceballos, Félix Suazo, Ermy Taño, Rubén Torres Llorca, Pedro Vizcaíno, and Carlos García. Why that sudden turn toward geometric abstraction by so many Cuban artists?” This note preceded the article “La retro-abstracción geométrica: un arte sin problemas: es sólo lo que ves” [Geometrical Retro-Abstraction: An Art without Problems; What You See Is What You See], which the critic and editor Desiderio Navarro published in La Gaceta de Cuba, in June 1989. The note was the show itself. Es sólo lo que ves existed merely by hearsay and in Navarro’s text, made up of a series of blank pages interrupted by tiny numbers and footnotes. Like the show, the text existed only in its glosses, in marginal comments.

In his thesis “Arte abstracto e ideologías estéticas en Cuba,” the researcher Ernesto Menéndez-Conde considers Es sólo lo que ves as part of a long debate about abstraction, which has often been identified as a neutral, uncommitted art. In a paradoxical way, and perhaps unconsciously, the avant-garde of the 1980s came close to the most orthodox line in the polemic that had opposed abstraction and social commitment: “Es sólo lo que ves was, in that sense, one more piece in that debate. Young people were assuming (repeating) the position that frequently, in Cuba and Latin America, was held by Marxist parties who saw abstraction as an art that was complicit in a certain oppressive order.”21

With all its ambivalence, that question about the sudden turn by Cuban artists toward geometrical abstraction would resonate a couple of months later with the unusual turn by Cuban artists toward baseball. Rather than qualify abstraction or the playing field as neutral, “without problems,” both gestures could be read as a politicization of those spaces: as when Saavedra paints a still life and writes on it “Art a weapon of struggle” (1988); or when the group AR-DE met every Wednesday at 23 and G just to announce that it would produce no action because it had been threatened and in that way, as the artist Juan-Sí tells it, made its most effective action.22 “The political,” Jacques Rancière reminds us, “happens generally ‘out of place,’ in a place that was thought to be not political.”23

In the migration from one space to another, from art to sports, for example, there is also a certain renunciation, or weariness, hope, stimulus, obligation, desire, responsibility, fantasy—as in the migration or exile of almost an entire generation of artists in a short period between 1989 and 1991. In the clandestine newspaper Memoria de la posguerra, Tania Bruguera’s project in the early 1990s, the critic and theorist Lupe Álvarez suggested, “Already toward the end of the last decade, the usual commentary in intellectual circles was a sort of complacency among cultural institutions before the emigration of key figures in the art movement. It seemed a wish to remove them from the game was prevailing, to neutralize the focus of conflict which that movement had generated, in taking on a esthetic and ideological debate for which our society was not prepared.”24

Ready to Win

- Withdrawal from, withdrawal to, the promised land

- Withdrawal from a utopics of the horizon

- Withdrawal from the public into the private . . . from the epic into the mundane

- Withdrawal from the collective to the individual

- Withdrawal from political controversy

- Withdrawal from confrontation with the Institution of Art

- The partly satirical withdrawal from satire to metaphor

- Withdrawal from the conceptual to the visual

In these eight points, the writer and curator Rachel Weiss breaks down the interlude “Withdrawal” in her invaluable study To and from Utopia in the New Cuban Art. That section opens with a photo of the Ball Game, taken by José A. Figueroa, and the author makes the only explicit reference in her book to La plástica joven se dedica al béisbol: “In 1989, at the height of the censorship crisis, pretty much all of the artists got together to withdraw. ‘If we can’t make art,’ they declared, ‘we’ll play ball.’ That act of collective withdrawal is still regarded as a high point of the poetics, and the politics, of the new Cuban art.”25

I would like to put into friction that image of the “withdrawal” with another snapshot of the Ball Game in which the artists exhibit a banner with the letters LPV: “Listos para vencer” [Ready to win] the slogan that has accompanied Cuban sports since the early 1960s. The slogan itself—like “Arte o muerte: venceremos” [Art or Death: We Shall Overcome]26 of the group Arte Calle—carries the echoes of a symbolic battle that was reinscribed in 1989 in another field of play. Although in retrospect La plástica joven . . . can be read as the staging of a withdrawal, a “swan song,” I would like to oppose—even if it’s like political fiction—the gesture of antagonism and confrontation that the Ball Game implied.27.

Taking up Weiss’s phrase again, I suggest we pause at the moment when she describes how the artists “got together” and has not yet mentioned “to withdraw.” Let’s stop at that brief instant to consider the “being together”—and facing another—as part of a politics put into practice by the Ball Game, a demonstration and a manifesto. More than a merely reactive performance, it had to do with the invention of other forms of self-organization and collective protest in a repressive context. If, on the one hand, the Ball Game made visible the limits of what is permissible, from all that could no longer be done, it certainly extended the limits of the possible, with a collective and political celebration. I wonder then, beyond victories or defeats, what does it mean now to invoke that time when almost an entire generation got together to declare itself “ready to win.”

Tamara Díaz Bringas is a curator and researcher. She held a scholarship in the MACBA Independent Study Program (PEI), Barcelona (2008–9) and holds a BA in art history from the Universidad de La Habana (1996). From 1999 to 2009 she was curator and editorial coordinator at the independent project TEOR/éTica, San José, Costa Rica. Her cocurated exhibitions include: Playgrounds. Reinventing the Square (with Manuel J. Borja-Villel and Teresa Velázquez), Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, 2014; 31 Bienal de Pontevedra: Centroamérica y el Caribe (with Santiago Olmo), Pontevedra, 2010; and The Doubtful Strait (with Virginia Pérez-Ratton), TEOR/éTica, San José, 2006.

This essay originally appeared in the Summer 2014 issue of Art Journal.

- La última exposición: El artista del mes, Castillo de la Real Fuerza, Havana, September 6, 1989. The catalogue, with a text by Gerardo Mosquera, was censored. ↩

- Gerardo Mosquera, “Seis nuevos artistas cubanos,” in Contemporary Art from Havana, exh. cat. (London: Riverside Studios, 1989, and Seville: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, 1990). ↩

- Osvaldo Sánchez, “Flavio Garciandía en el Museo de Arte Tropical” (1995), rep. in I Insulted Flavio Garciandía in Havana, ed. Cristina Vives (Madrid: Turner, 2009), 206. ↩

- 5 million square miles ↩

- Speech by Fidel Castro Ruz on the occasion of Mikhail S. Gorbachev’s visit, celebrated at the Palacio de las Convenciones, Havana, April 4, 1989, at www.cuba.cu/gobierno/discursos/1989/esp/f040489e.html, as of June 27, 2014. ↩

- Even if a good number of them subsequently took part in the group show El objeto esculturado, at the Centro de Artes Visuales, Havana, 1990. ↩

- Alexis Somoza, La obra no basta: Ensayos sobre arte, cultura y sociedad cubana (Valencia, Venezuela: Raúl Clemente Editores, 1991), 76, cited by Eugenio Valdés Figueroa, “El arte de la negociación y el espacio del juego (el coito interrupto del arte cubano contemporáneo),” in Cuba, siglo XX: Modernidad y sincretismo (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain: Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, 1996). ↩

- Luis Camnitzer, New Art of Cuba (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994), 323. ↩

- Post from August 20, 2013, at: http://losliriosdeljardin.blogspot.com.es/2013/08/squeeze-play.html. Regarding the Ball Game, see also: http://losliriosdeljardin.blogspot.com.es/2009/05/la-plastica-joven-se-dedica-al-baseball.html ↩

- Glexis Novoa in “Glexis Novoa: el pesimismo creativo,” interview by Emilio Ichikawa, at www.eichikawa.com/entrevistas/entrevista_Glexis_Nova.html, as of June 27, 2014. ↩

- Cristina Vives, “¡Bases llenas! . . . o, el arte en la calle (Una brevísima ojeada al arte público de los 80 en Cuba),” ICP, Revista del Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña (San Juan, Puerto Rico), special issue on the Trienal de Gráfica, December 2004. ↩

- Eugenio Valdés Figueroa, “El arte de la negociación y el espacio del juego (el coito interrupto del arte cubano contemporáneo),” in Cuba, siglo XX: Modernidad y sincretismo (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain: Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, 1996). ↩

- Elvia Rosa Castro, “Play Off (también, a propósito de Antonia),” Artecubano 1 (2001) ↩

- Orlando Hernández, Stealing Base: Cuba at Bat, exh. cat. (New York: The 8th Floor, 2013). ↩

- Rachel Weiss, “A Certain Place and a Certain Time: The Third Bienal de la La Habana and the Origins of the Global Exhibition,” in Making Art Global (Part 1): The Third Havana Biennial 1989 (London: Afterall, 2011), 14. ↩

- A line from “La isla en peso,” a 1943 poem by Virgilio Piñera. ↩

- Gerardo Mosquera, “The Third Bienal de La Habana in Its Global and Local Contexts,” in Making Art Global (Part 1), 78. ↩

- Aylet Ojeda, “Cuéntame un cuento: una entrevista con Lázaro Saavedra,” in Arteamerica 8 (Havana: Casa de las Américas, no date), at www.arteamerica.cu/8/debates.htm, as of June 27, 2014. ↩

- Benjamin Buchloh, “Hans Haacke: la urdimbre del mito y la ilustración,” in Hans Haacke: Obra Social, exh. cat. (Barcelona: Fundació Antoni Tàpies, 1995), 286. ↩

- Osvaldo Sánchez, “Utopía bajo el volcán: La vanguardia cubana en México,” in Plural (México D.F., 1992), rep. in Nosotros los más infieles: Narraciones críticas sobre el arte cubano (1993–2005), ed. Andrés Isaac Santana (Murcia: CENDEAC, 2007), 113. ↩

- Ernesto Menéndez-Conde, Arte abstracto e ideologías estéticas en Cuba (diss., Duke University, 2009), 6. ↩

- Interview with Juan-Sí in Glexis Novoa’s video El canto del cisne (2010). ↩

- Jacques Rancière, “La división de lo sensible: Estética y política,” trans. Antonio Fernández Lera (Salamanca: Consorcio Salamanca, 2002). ↩

- Lupe Álvarez, “Reflexión desde un encuentro,” in Memorias de la posguerra 1, no. 2 (Havana, June 1994): 18. ↩

- Rachel Weiss, To and from Utopia in the New Cuban Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 164. ↩

- Banner in the performance No queremos intoxicarnos, with which the group Arte Calle interrupted a meeting of art critics at the Sala Rubén Martínez Villena, Havana, 1988. ↩

- “Swan song” is how the artist Rubén Torres Llorca refers to the Ball Game in Glexis Novoa’s video El canto del cisne (2010) ↩