From Art Journal 73, no. 4 (Winter 2014)

It seems obvious to state that photographs play a central role in our ability to study participatory art. Art historians, however, have largely bracketed this as an issue that might be important for how we conceive the politics and aesthetics of participation.1 The art historian Claire Bishop has described photographs of participation as somewhat impoverished, decidedly peripheral to the work itself: “Casual photographs of people talking, eating, attending a workshop or screening or seminar tell us very little, almost nothing, about the concept and context of a given project.”2 With performance art, on the other hand, the recent interest in documentation has bordered on the obsessive. Scholars including Amelia Jones, Philip Auslander, Jane Blocker, and Mechtild Widrich have theorized extensively about the performance document, awarding it a crucial, even paradigmatic, role in the ontology of performance.3

This essay seeks to cross-pollinate the analysis of participation with an attention to the documentation of live art that draws on performance studies, in order to conceptualize the specific operation of the participation document. Photographs of participatory artworks most often represent participation by showing participants. These images partake in the production of ideas about the agency of the participant audiences pictured, ideas that are important for the conceptualization of participation as such. Photographs of participation typically position participant agency as something anterior to a given project, which the project simply facilitates, and which is reflected transparently in the photograph. In fact, documentation images and the representation of participant agency they materialize are bound up with the production of institutional and artistic authority.4

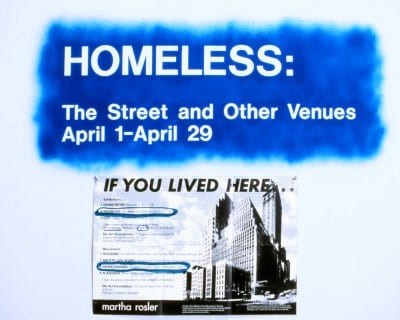

My case study is a project by an artist explicitly concerned with the political agency of her collaborator-participants, and moreover, with the photographic representation of the agency they exercised in participating. In 1989, the Dia Art Foundation hosted If You Lived Here . . . by Martha Rosler at its Soho spaces on Wooster and Mercer Streets in New York. If You Lived Here . . . was a highly political project. It treated themes of urban homelessness, gentrification, and city planning, and encompassed both sequential gallery installations (Home Front, Homeless: The Street and Other Venues, and City: Visions and Revisions) and open forums, featuring panels of speakers followed by public discussion on these topics.5 Among the project’s participants were not only members of New York City’s various art communities, but also activists involved with the issues. These included the members of Homeward Bound Community Services, a self-organized group of homeless people who had coalesced in 1988 to create an encampment in front of City Hall, protesting Mayor Ed Koch’s lack of concern with homelessness. The majority of Homeward Bound members were African American, and most were male. For Homeless: The Street and Other Venues, the second exhibition in If You Lived Here . . ., the group maintained an office within the gallery installation and participated in the forum on homelessness held concurrently with the show.

Homeward Bound’s participation in Rosler’s project raises the question of the agency of subaltern groups within the participatory artwork. The members of the group were in a position of otherness, in terms of class and race, to the privileged, largely white, art-world milieu that Dia represented. The project made no structural change in their lack of privilege, due to their position outside lines of social mobility.6 I have been unable to find any members of the group to ask them about the project, and the last written reference I have to Larry Locke, its most prominent member, is a newspaper article of May 1990, in which he is cited as saying that on a good day, he can make up to two hundred dollars selling the Street News on the Upper West Side.7 How, in this situation, can we understand the project’s relationship to the group members’ political agency? That question is connected to the issue of the articulation of this agency within the project, at a number of levels. Considering Homeward Bound’s participation involves thinking not only about its members’ collaborative involvement in the project, but also about their ability to assert their right to democratic political participation in a wider sense. As I will demonstrate here, the terms under which Homeward Bound became visible within If You Lived Here . . . were a topic of complex negotiation among Rosler, Dia, and the group members themselves. That negotiation spanned the project in its moment of liveness, and the creation and use of its photographic documentation.

If You Lived Here . . . took place in the context of a downtown New York art scene—and a decade in American art more broadly—when the politics of representation stood front and center for artists on the Left. Against this backdrop, it is specifically Rosler’s longstanding concern with the politics of documentary photography that makes her work ideal for analyzing the political stakes of photographs of participatory artworks. Her attitude toward the photographic documentation of Homeward Bound’s participation was informed by her well-known critique of American documentary photography, as expressed in her 1981 article “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (on Documentary Photography),” and in the photo-text work The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems (1974–75) which that essay was written to elucidate.8 “Documentary, as we know it,” Rosler writes, “carries (old) information about a group of powerless people to another group addressed as socially powerful.”9 Whereas “In, Around, and Afterthoughts” and The Bowery are critical works that define the politics of photographic representation negatively, by stressing what documentary should not be, the case study of the Rosler–Homeward Bound collaboration illustrates the strength of Rosler’s commitment to positive representation of an oppressed group. Moreover, Rosler’s analysis of the way in which documentary seems most neutral at the moment when it most forcefully reproduces a classed structure of viewing alerts us to how participatory art documentation is dependent on codes of representation in relation to which participants occupy unequal positions, depending on factors including their race, class, and gender.

It is important to emphasize that these layers of overdetermination do not render meaningless subaltern participants’ experiences of a project. We need to analyze the production and circulation of articulations of agency across the entire terrain of a participatory artwork, including both live events and their documentation, with particular attention to the impact of those articulations on experience. As such, my analysis here involves a greater attention to participant experience than is typical for accounts of participatory art, which remain focused largely on the significance of participation to artists and critics.

Homeward Bound’s Visibility inside and outside the Gallery

Rosler initially came into contact with Homeward Bound through her assistant, the urban activist Dan Wiley, who had at one point slept along with the group in its encampment in City Hall Park.10 In the park, the group’s work had included outreach to both homeless and housed people in order to foster political participation, for example through registering people to vote. Homeward Bound’s participation in If You Lived Here . . . took place in spaces that were highly visible to art audiences, namely Dia’s gallery at 77 Wooster Street that hosted the Homeless exhibition, and also the “Homelessness” public forum (or town-hall meeting, as it was called within the project), held in Dia’s nearby 155 Mercer Street space. When I interviewed Rosler, she spoke about Homeward Bound’s participation in terms of the practical resources the project provided to it. She stated that the group wanted a place to make phone calls, send faxes, and hold meetings and workshops.11 This was a form of support it had received from other organizations, such as the Food and Hunger Hotline, which in late 1988 was allowing the group to use a desk and telephone in its offices.12 At Dia, however, Homeward Bound was not allotted a private or semiprivate space from which to work, such as, for example, the front conference room in Dia’s offices on Mercer Street. That space had been used for roundtable discussions during the art collective Group Material’s Democracy, the project that proceeded Rosler’s, and to which it was connected conceptually in Dia’s exhibition planning.13 Instead, Homeward Bound’s temporary office was located in a gallery, surrounded by artworks by various artists (including homeless artists) on the theme of homelessness. The location of the office not only in a public space but in the gallery, a space explicitly associated with display, made it clear that the members’ visibility itself was an important element of their participation.

In the gallery, the members of Homeward Bound were on display to exhibition visitors, some of whom noted this with discomfort. The artist and writer Gregory Sholette, who contributed a work to the show, has no memory of seeing Homeward Bound in the gallery, but states that he remembers questions circulating about “representations of homeless people in the flesh, so to speak, as being somewhat problematic.”14 Camilla Fallon, an artist who worked at Dia in the Wooster Street gallery, echoes Sholette’s comments. Fallon remembers that the situation was generally an uncomfortable one for everyone involved, including the Homeward Bound members.15 Andrew Castrucci of the Bullet Space art squat also remembers feeling discomfited by the situation, and ambivalent about whether it simply objectified the group or productively created a challenging representation.16 These memories suggest that perhaps what was disconcerting was a feeling of display that circulated among all those present, including not only Homeward Bound members but also gallery visitors and employees.

The comments of Fallon and Castrucci take into account their own affective implication in the situation, in the form of the feeling of discomfort. Two journalists responding to the show were less self-reflexive in their critique, targeting Rosler personally and harshly for what they perceived as the problematic aspect of the exhibition. In a clearly scandal-seeking article for New York magazine, Peg Tyre and Jeannette Walls wrote, “Artist Martha Rosler apparently believes that New Yorkers don’t fully appreciate homeless people. Maybe that’s why she’s including some in her current show.” The authors then quote an unnamed source who says, “The whole thing is in very questionable taste. . . . Some homeless people were invited to the opening of the show and were disgusted when these radical-chic downtown types in Lagerfeld clothes gawked at them.”17

Contrary to Tyre and Walls’s accusations, the paradox of Homeward Bound’s visibility within Homeless was not simply imposed on the group by Rosler, but was a role it accepted with awareness of its complexity. Minutes from a meeting of Homeward Bound, entitled “Meeting Wed. Apr. 5th [1989],” show the group attempting to think through the ways in which this situation both posed problems and offered advantages for their work. A list in these minutes under the headings “HB problems” and “justifications” contains the following items:

HB problems

- cant sleep there

- we not only fundraisers

- we are on display (see below)

justifications

- we’d take 6 people off streets serving guys in trains + streets + drop in centers = direct service those brainwashed

further justifications

- Education

- Self help Madhousers from Atlanta public demonstration temp [illegible]

- Employment opp referrals 18

In the list of problems, “we are on display” is followed by the qualification “(see below),” but the rest of the extant notes fail to elucidate the comment. Among the justifications, which include employment and contacts with the Atlanta-based Mad Housers activist housing collective, which also participated, I argue that “education” was the most important conceptual stake for Homeward Bound. This investment in education was closely connected to the condition of being on display.

Rosler, in “Fragments of a Metropolitan Viewpoint,” her essay for the project book Dia published on If You Lived Here . . ., stresses the self-determination of Homeward Bound’s participation in the project. “[In an] instance of the self-production of meaning,” Rosler writes, “the group Homeward Bound maintained an office in the gallery (and participated in the forums), as advocates for themselves and other homeless people.”19 But this self-production of meaning was not free of constraints. The clearest example of the limitations placed on Homeward Bound’s use of the gallery space arose in relation to the question of whether or not its members would be able to sleep there. Rosler had originally intended for Homeward Bound to be able to sleep in the gallery and had included beds as part of the installation for that purpose.20 But this plan ran aground when Dia announced that the terms of its co-op share for the Wooster Street gallery space prohibited residential occupancy. In a letter dated April 7, 1989, Dia director Charles Wright explained this state of affairs to the members of the group.

To the People of Homeward Bound,

We are sorry for the misunderstanding about our ability to open up our space at 77 Wooster Street for you to stay in. We do not actually own the space but own the shares in the building coop which gives us the right to use that space for our program. We are not allowed to use the space for people to live in but only to be open to the public for exhibitions and related activities. . . .

We were very pleased when Martha Rosler told us you would be participating in this project, using the space to work from. We hope it will bring you into contact with many people who would not otherwise know about your concerns and your work and who will be interested in knowing more about you and supporting you. We expect that any press coverage received about the project would discuss your organization and its work.21

The letter elucidates the relationships between Dia, Rosler, and Homeward Bound, while clarifying the permissible use of the space. Moreover, Wright emphasizes what Homeward Bound can gain from the situation: visibility in the media and the wider community.

The question of whether Homeward Bound members would be able to sleep in the gallery had material significance, as noted in the first justification listed in the meeting notes: “we’d take 6 people off streets.” But it was also important for the group’s political work, as illustrated by its long-term encampment in front of City Hall that started in June 1988, and lasted for approximately two hundred days.22 The most detailed documentation of this occupation is found in Sleeping with the Mayor: A True Story (1997), a novel by former Village Voice journalist John Jiler.23 Jiler’s book, which chronicles the rise and fall of Homeward Bound, provides significant insight into the importance of the group, but is simultaneously problematic as a historical source due to its degree of fictionalization. The book asserts the truth of its narrative even in its title. But it then opens with a disclaimer, in which Jiler states that due to the stigma of homelessness, he has changed the names of some characters and altered identifying information. Some figures, though, are identified by their real names, including Homeward Bound leaders Locke and Duke York, the politician Abe Gerges, and Rabbi Marc Greenberg of the Interfaith Assembly on Housing and Homelessness, an organization which sponsored the group.

Jiler stresses that Homeward Bound’s existence was bound up from the very beginning both with the political power of visibility, and with complex power dynamics between the group and various institutions. As he relates it, Homeward Bound was galvanized, if not initiated, by Rabbi Greenberg and the Interfaith Assembly. Greenberg coordinated the overnight vigil against homelessness on June 1, 1988, at which Homeward Bound originally formed.24 That vigil segued into its semipermanent encampment. Jiler foregrounds Homeward Bound’s amateur yet successful manipulation of the City Hall media. He emphasizes the importance of public and media visibility, and not simply housing or resources, as a central concern for the group. As he casts it, the group members’ initial overnight vigil and then their continued habitation of City Hall Park were publicity stunts, timed to coincide with the city’s budget meetings. They resulted in media coverage and the attention of passersby who walked through the park.25 For example, the artist Bill Batson, who chaired the “Homelessness” town hall meeting held during the exhibition, states that he first encountered Homeward Bound when walking through City Hall Park to go to work. The group impressed him with its organization and activism and became instrumental in his own radicalization.26

Jiler’s narrative and Batson’s memory give context to the importance to Homeward Bound of sleeping in Dia’s gallery. During the City Hall Park encampment, sleeping in the park was central to attracting media attention, Homeward Bound’s strongest means of exercising political agency. In a New York Times article of November 28, 1988, the journalist Michael Marriott describes the group as “organized, stubborn and well spoken . . . also an eyesore and a political rotten egg for the Koch administration.”27 With this vocabulary, Marriot stresses both the literal visibility of the group (“eyesore”) and the political potency of that visibility (“rotten egg”). The term “political rotten egg” casts the group’s political power as effective insofar as it is affective, something that brings about emotional and bodily discomfort.

The participants in If You Lived Here . . . cited above, as well as Tyre and Walls in their article, cast viewer discomfort as an unintentional or unfortunate aspect of Homeward Bound’s participation. Marriott, however, depicts it as a political tool. Jiler also represents this affectively potent visibility as Homeward Bound’s key political asset, the biggest thing it had to offer to Interfaith and a whole network of supportive organizations that had a political investment in advocacy to end homelessness. In a letter to members shortly following their participation in Homeless, the group thanks forty-two organizational sponsors, including “Dia foundation” and also Channel 41, the American Civil Liberties Union, ACT UP, the Manhattan Borough President’s Office, the Pratt Institute, and multiple churches. It also thanks almost seventy individual sponsors, including City Council members, a senator, and a congressman.28 These individual and organizational agents not only provided Homeward Bound with resources, media coverage, and political advocacy, but also had something to gain from Homeward Bound in terms of how the group made homelessness visible.

The Audience as Pedagogical Subjects

One of the central reasons Homeward Bound decided to submit to visibility at all was its members’ investment in propagating a specific model of audience viewership. That model took the viewer as a pedagogical subject, who through Homeward Bound’s activities would come to see homeless people in a more positive light, but would also gain a new understanding of her- or himself as a site of reciprocal visibility. Within Homeless, this interpellation by Homeward Bound of the audience member as a learning subject spanned both the gallery show and the town hall meeting “Homelessness: Conditions, Causes, Cures,” at which the Homeward Bound leader Locke was a speaker.

In the gallery, the positioning of the viewer as a learner entailed a metaphorical casting of that viewer in the role of a homeless person. As stated above, the beds which Rosler originally placed in the gallery remained part of the installation after Dia made it clear that the group was not allowed to sleep in the space. Stripped of their intended purpose, the beds retained a representational function of presenting the gallery as if it were a homeless shelter. This impression, that the gallery was to be understood as mimicking the institutional spaces that homeless people frequent, was reinforced by the presence of Homeward Bound’s office. The office evoked a friendly, grass-roots version of the type of bureaucratic government office where homeless New Yorkers might go to obtain the social services available to them. Despite the fact that members of Homeward Bound were present in the gallery only on a limited basis, as I will discuss below, having their office there established a sense that they had a right to the space. They had a degree of control of the space that gallery visitors, who might see the show only once for a few minutes, did not.

In the installation, the forms of material support that service organizations provide to homeless people functioned symbolically to position the viewer as a learner about the problem of homelessness. This was underscored by the fact that soup and bread were served at the exhibition opening.29 The symbolic nature of this gesture is evident from the fact that for the majority of visitors at the opening, the food would not have been a necessary source of bodily sustenance. The serving of soup might on one level seem to be a crass echo of a real soup kitchen, with privileged gallery-goers invited to “play homeless.” But viewed in another light, it can also be read as interpellating the viewer as someone in need of a certain pedagogical intervention, a repositioning in relation to the question of homelessness. That pedagogical intervention was supported by Homeward Bound’s office, and by the many artworks by both homeless and housed artists that provided information about homeless life, and about diverse political and emotional responses to it.

Homeward Bound’s desire to educate viewers, and thereby to create a new pedagogical situation that reversed typical power dynamics between the homeless and the housed, is evident in a speech given by Locke at the “Homelessness” town hall meeting. On the audio recording of the meeting, Locke’s voice is slow and deliberate as he delivers his speech.

Thank God for all the things that he’s blessed us with, in the park and out of the park. You know—we—have emerged, as a group of homeless people, to the extent that we now, some of us, are working in the capacity of educating people like yourself. . . . Instead of you just educating me, I have the opportunity now to educate you to some extent. [pause] And that’s the idea that’s going around the homeless community. Hey, we, in fact, have something to offer. We can educate people too! So wonderful.30

Locke locates the group’s very emergence in the degree to which its members are able to function as educators. He connects working, a politically contentious issue surrounding homelessness (reportedly, Mayor Koch used to yell “Get a job!” at the members of Homeward Bound as he walked through the park), to the practice of education.31 The audience at the “Homelessness” forum was made up of people from various art communities in New York as well as others interested in the problem of homelessness. Locke addresses the audience as other, “people like yourself,” implicitly interpellating them as privileged. In doing so, he highlights their status as visible members of a generalized category. He uses the concept of education rhetorically to generate a reciprocal relationship, one that comes to replace middle-class viewing of homeless people as objectified others, or as Rosler put it in “In, Around, and Afterthoughts,” as specimens of “a physically coded social reality.”32

Locke closes his remarks with another role reversal, when instead of thanking Dia as a host institution, he states that Homeward Bound is “helping sponsor the project at Dia.” He thus casts the group in a position of power to support Dia and Rosler’s project, instead of as the recipients of charity or support through the project. In this way, Locke points to the institutional frame within which Homeward Bound’s participation takes place, but depicts that frame less as something that places limitations or qualifications on Homeward Bound’s work, than as something that its members themselves have the power to reinforce.

Both Homeward Bound’s participation in If You Lived Here . . . and its City Hall encampment might be understood as forms of tactical spectacle, designed to change public attitudes toward homelessness. But an important difference between these contexts lay in the discourses to which each space was attached. The presence of Homeward Bound within the gallery space elicited discourses about representation and viewership that seemed less relevant during the City Hall encampment. Some of these concerns had particular resonance with Rosler’s existing practice, and specifically with her critique of documentary photography.

Homeward Bound, Photography, and Documentation

For Rosler, the photographic documentation of Homeward Bound’s participation in the show held a pedagogical importance that paralleled Homeward Bound’s own investment in educating the audience. Dia’s archive includes two images showing Homeward Bound members, which appear to have been taken from a set of ten originally in Rosler’s possession. The authorship of these images is unclear: they might have been taken by Rosler herself, by the photographer Oren Slor, who was contracted by Dia to document all of the installations for If You Lived Here . . . , or by someone else.33 Following the completion of If You Lived Here . . ., these images of Homeward Bound became bound up in a terse negotiation between Rosler and Dia about how Homeward Bound should be represented in the project book.

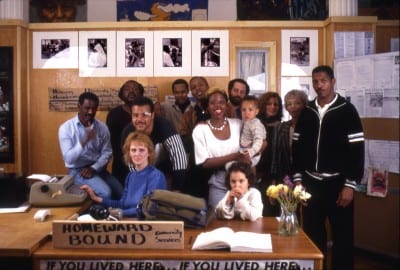

The photographs in Rosler’s archive all appear to have been taken in quick succession. Click, wind, click. In one image, a group of thirteen people is posed behind a wooden desk, in front of a temporary wooden divider, behind which we can see the gallery wall. The wooden divider bears a number of photographic portraits, various typed information sheets, at least three children’s drawings, and a small banner handwritten on brown paper headed with the words “Housing” and “Homelessness.” In the foreground of the photograph, a piece of wood stands on the desk, with the words “Homeward Bound Community Services” written in black marker.

The people in the group stand close together, right in the center of the image. There are four women, seven men, a baby, and a small girl. A woman with strawberry blonde hair and a bright blue sweater sits at the desk. One of her hands is poised on the typewriter. A man leans over the back of her chair, his shoulders rounded, with a smile on his face and a bandage on his left eyebrow. A woman holding the baby smiles broadly. Except for a bearded man blinking in the background, all group members look directly into the camera. On the whole, they seem friendly, and connected to each other. They smile, but not in a strained way.

It might seem obvious to state that this image represents Homeward Bound as present within its office space in the gallery. But in fact, the actual amount of time that its members spent in the gallery and the extent to which the space operated functionally for them as an office remain unclear. Gary Garrels, Dia’s Director of Programs at the time, states that he was never clear about how the office was actually functioning. He attributes this to the fact that he did not have his office in the same building, and hence was not at the exhibition all the time.34 Camilla Fallon recalls that the time Homeward Bound actually spent in the gallery was quite limited: “Martha may have brought people in for a day, and that would probably have been it.”35

Dan Wiley states that the gallery office was set up as a space the group could use, and that the goal of the project was more to make the space available than to ensure that they would be there the whole time. “It was a space they could use and be,” Wiley states, “and a space for interaction. [The goal] was opening it up.”36 For Wiley, the aim was more to create a space of possibility than to fix a regular commitment to presence. The image, though, with its crowded and friendly group composition, and the woman’s hand poised on the keyboard in order to signify work taking place, gives the impression of the group’s energy, labor, and collective presence filling up the space. The photograph fixes the group’s use of the gallery, which was occasional and somewhat controversial, into a solid image of uncontested collective presence.

One of the strongest visual characteristics of the images of Homeward Bound is their posed quality. They show Homeward Bound specifically posed for the photographs. Or rather, of the photographs, the one I described above shows a more or less complete pose: the members arranged, standing and sitting, behind the desk. Rosler’s archive contains another image taken directly before or after the clearly posed one, and it shows the pose either coalescing or coming undone. A tall man in a tracksuit on the right-hand side is speaking, standing with his palms outspread, facing up. He seems to be telling a joke, evoking a laugh from the bearded man in the gray suit, now a blur on the right side of the frame. The woman in blue glances over at him, and the one holding the baby gives him a marked look, potentially indicating irritation or offence. Behind the man making the joke, a woman who smiles demurely in the posed image cracks a wider grin. The little girl looks shyly off to the side. Only the smiling woman and the man second from the left are still looking into the camera. On the whole, the group appears here more dynamic, and less united. The interactions among the people pictured are more visible. We get less of a clear presentation of them as a unit, but more hints at how they might have related to each other.

What is the representational significance of the pose is in these images? In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes describes the pose as a process in which one actively transforms one’s body into an image.37 bell hooks, writing on the significance of personal snapshots in African American life, similarly describes posing as an act of self-fashioning.38 In the images of Homeward Bound, the collective pose unites the group visually into a compositional unit, and thereby conceptually into a common project. The pose claims for Homeward Bound the visual vocabulary of the team, the collaborative, the club, thereby stressing its collective organization to meet specific, clearly legible goals. Moreover, the fact of the posing articulates a relation with the viewer of the image. Craig Owens, in his 1984 essay “Posing,” argues that in the photograph, the posed subject’s look figures the gaze of the photographer who captures the scene.39 The act of posing thus becomes the visual manifestation, in the image, of someone else’s future act of looking at the photograph. In this light, the pose in these images of Homeward Bound might be read as a visual analogue for Locke’s address at the public meeting. Like his speech, it assigns privileged audiences a place in relation to the homeless people who are positioned to function as their educators, but without positing a relationship of sameness between them.

Rosler has not theorized the importance of the pose explicitly, either in relation to photography in general or to the Homeward Bound images in particular. But in her writings on photography, what does emerge at various points is a critique of spontaneity, which might be considered the opposite of the pose. In general, Rosler associates spontaneous-seeming photographs with an ideological function, in which the photograph is assumed to capture a single moment of truth, unsullied by the investments of the photographer.40 In “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (on Documentary Photography),” Rosler identifies two “moments” of documentary photography, the first an “immediate” moment in which an image is captured “as evidence in the most legalistic of senses, arguing for or against a social practice and its ideological-theoretical supports.”41 This is followed by a second, “aesthetic” moment, when the viewer takes pleasure from the formal qualities of the image. In these two moments, proof and pleasure unite to create a powerful discourse in which aesthetic appeal cloaks the photograph’s ideological function. In essence, for Rosler, the appearance of spontaneity has an antipedagogical effect, in that it keeps viewers from becoming aware of the ideological structures that shape the production and experience of the photograph.

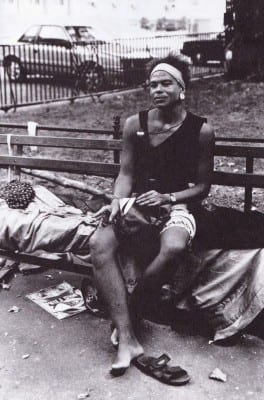

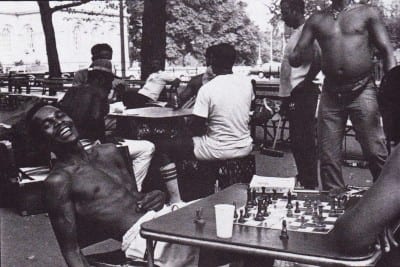

Correspondence in Rosler’s personal archive indicates that she wanted one of the posed images of Homeward Bound included in If You Lived Here: The City in Art, Theory, and Social Activism / A Project by Martha Rosler, the book that Dia published for the project. Instead, the book includes a selection of Alcina Horstman’s black-and-white photographs of Homeward Bound members in their City Hall park encampment. Of the images included in the book, the largest is an individual portrait, and all depict the members of Homeward Bound as friendly and cheerful amid the obvious squalor of the park. On a stylistic level, Horstman’s photographs resonate with the American documentary tradition that Rosler critiques. In particular, they display an attempt to capture their subjects spontaneously in a way that evokes that tradition.

From the correspondence records, it seems that the inclusion of Horstman’s images instead of the posed ones was the result of a series of miscommunications, exacerbated by the fact that Rosler was geographically distant, teaching in South Africa during a crucial phase of manuscript preparation. In a 1990 fax to Dia director Wright, Rosler expressed displeasure at the photographic representation of Homeward Bound in the book:

I said long before I left that it was crucial to have a picture of Homeward Bound sitting or standing behind their desk at the exhibition, because there would be a significant betrayal involved in representing them in the book as though they were “just” more homeless individuals camped out in the park. The whole thrust of their participation in the show was that this was not the image either I or they wished to present.42

Rosler depicts the choice of photograph for the book as cutting to the heart of her and Homeward Bound’s collective goals for the project. Wright, in his reply, makes it clear that the posed images can no longer be included in the book, but also expresses disagreement with the idea that the photo of Homeward Bound in the exhibition office is essential to depicting the group as exercising agency. Wright writes:

While we cannot now substitute in the other Homeward Bound photo, it looks to one, as another, less involved viewer, that the pictures we have do not merely depict a dispossessed group, homeless in the park. They are more dynamic than that. There is clearly political organization and action taking place, checkers game notwithstanding. . . . To save money and time, the change wasn’t made.43

In this exchange, Rosler and Wright approach the images from two strongly differing positions, which appear almost unintelligible to one another. For Rosler, the central question is that of an ethics of representation. For her, the ethical image, the one that refuses to reduce homeless people to a stereotyped generalization, provides the jumping-off point for a viewer experience with the potential to create political change. Wright, on the other hand, approaches the issue on the basis of an idea of average audience viewership. As the director of a small, financially struggling organization, he was working to use the resources available to create a publication that effectively presented If You Lived Here . . . to the public. From his perspective as expressed in the fax, the specificities of Homeward Bound’s representation would be largely unnoticeable to readers not involved with a particular set of debates.

Though Wright claims that the differences between the two sets of images would fly under the radar for most viewers, I agree with Rosler that the experiences of viewership elicited by the two sets of images vary radically. Only in the posed images does photography operate self-reflexively to give the group an opportunity to engage with the process of its representation. Furthermore, the photographs of Homeward Bound behind the desk, in the differences between the posed and the less-posed images, highlight what the rejection of spontaneity in favor of pose both makes visible and forecloses from visibility. In the more formally posed, less animated of the two images, we are less able to project ourselves into the image as an imagined situation, to think that we know something about these people and what their relationships were like. The pose, to this extent, blocks a certain kind of knowledge, decreasing the image’s capacity to act as a space for the imaginary exploration of a past situation. This block is frustrating for the viewer, in that it closes down the pleasure of imaginary projection. But read from the perspective of Rosler’s approach to photography, it appears productive for precisely this reason: the posed images discourage an imaginary possession of the homeless by the mind of the curious viewer, who is no longer confidently able to think she or he holds authoritative knowledge of the people pictured.

At the beginning of this essay, I argued that photographic documents of participatory art projects show participants as a means of representing the ephemeral process of participation. Over the course of my analysis, the photographic image has emerged as a key site for the consolidation of the concept of participation as such. The posed pictures of Homeward Bound show how the photograph can weave the historical “fact” of participation from the messy and often unclear network of relationships that materialize within a given project.

Such images are, moreover, proliferating: the circulation of photographs of participants now encompasses not only the explicit presentation of artists’ projects after the fact, but also the visual culture of art institutions’ wider self-fashioning, particularly in social media. It is time to start looking carefully at these images and to analyze the work of meaning-making they perform. In particular, we should consider how they articulate collective experience in relation to the larger ideas structuring a project. As the Rosler–Homeward Bound collaboration demonstrates, both the formation of that collective experience in the live event and its subsequent articulation through documentation are the objects of negotiation among agents who hold different, sometimes incompatible, goals for the participatory project. Among these layers of overdetermination, recovering a hard kernel of self-determination on the part of subaltern participants is structurally impossible, but in its impossibility, remains an urgent object of analysis. It can lead, in the spirit of Rosler’s critique of documentary, at least to a greater awareness of how the concept of participation depends on our own disciplinary and institutional investments in producing both the visibility and the invisibility of these groups.

Adair Rounthwaite is writing a book entitled Asking the Audience: The Affective Politics of Participation in New York, 1988–89, under contract with the University of Minnesota Press. This fall, she will start a job as assistant professor of contemporary art at the University of Washington.

Thank you to Jane Blocker, Jenn Marshall, Amelia Jones, and Martha Rosler for their feedback on this work. Thanks also to my interviewees, especially Martha, and also Greg Sholette, Camilla Fallon, Gary Garrels, Bill Batson, Andrew Castrucci, Charles Wright, and Dan Wiley. This research was supported by doctoral and postdoctoral grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

This essay originally appeared in the Winter 2014 issue of Art Journal.

- See, for example, Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London: Verso, 2012), and “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October 110 (Fall 2004): 51–79; Grant Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), and The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011); Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (2001; Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 2006); Shannon Jackson, Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics (New York: Routledge, 2011); and Blake Stimson and Gregory Sholette, eds., Collectivism after Modernism: The Art of Social Imagination after 1945 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007). ↩

- Bishop, Artificial Hells, 5. ↩

- See Amelia Jones’s classic essay “‘Presence’ in Absentia,” Art Journal 56, no. 4 (Winter 1997): 11–18, reprinted in an updated version as “Temporal Anxiety / ‘Presence’ in Absentia: Experiencing Performance as Documentation,” in Archaeologies of Presence: Acting, Performing, Being, ed. Gabriella Giannachi, Nick Kaye, and Michael Shanks (New York: Routledge, 2012), 197–221. See also Amelia Jones and Adrian Heathfield, eds., Perform, Repeat, Record: Live Art in History (London: Intellect Ltd., 2012); Philip Auslander, “The Performativity of Performance Documentation,” PAJ 28, no. 3 (September 2006): 1–10; Jane Blocker, What the Body Cost: Desire, History, and Performance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004); and Mechtild Widrich, “The Informative Public of Performance: A Study of Viennese Actionism, 1965–70,” TDR 57, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 137–51. ↩

- Mechtild Widrich has recently argued that the exercise of authority is constitutive of documentation as such; in order for something to be accepted as a document, authority much be exercised. Widrich, “Process and Authority: Marina Abramović’s Freeing the Horizon and Documentarity,” Grey Room 47 (Spring 2012): 80–97. ↩

- If You Lived Here . . . is the subject of an essay by Nina Möntmann, “(Under)Privileged Spaces: On Martha Rosler’s ‘If You Lived Here . . .,’” e-flux journal 10 (2009). Möntmann has also contributed an essay on the project to Mousse magazine’s “Artist as Curator” series, detailing the Rosler project’s treatment of urban space. “The Artist as Curator: Martha Rosler, If You Lived Here . . ., 1989,” Mousse 44, no. 3 (2014): 3–18. ↩

- Gayatri Spivak, in a 2005 essay, (re)defines the subaltern as those removed from lines of social mobility. Spivak, “Use and Abuse of Human Rights,” Boundary 2 32, no. 1 (2005): 147. ↩

- Kathleen Teltsch, “Tabloid Sold by the Homeless Is in Trouble,” New York Times, May 24, 1990, B1. ↩

- Martha Rosler, Martha Rosler: 3 Works: 1. The Restoration of High Culture in Chile; 2. The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems; 3. In, Around, and Afterthoughts (on Documentary Photography) (Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1981). ↩

- Martha Rosler, “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (on Documentary Photography),” rep. The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography, ed. Richard Bolton (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990), 306. ↩

- Interview with Dan Wiley, New York, May 26, 2011. ↩

- Inteview with Martha Rosler, Brooklyn, July 21, 2010. ↩

- See Michael Marriott, “Homeless in Park Sticking to a Cause,” New York Times, November 28, 1988, B3. ↩

- Group Material’s Democracy ran from September 1988 to January 1989. It and Rosler’s project were conceived as two halves of the larger programming year “Town Meeting,” based on a recommendation made to Dia by the filmmaker and choreographer Yvonne Rainer. Dia published a book for each project; Group Material’s Democracy was documented in Democracy: A Project by Group Material, ed. Brian Wallis (New York and Seattle: Dia Art Foundation with Bay Press, 1990). ↩

- Telephone interview with Gregory Sholette, November 28, 2011. ↩

- Telephone interview with Camilla Fallon, December 6, 2011. ↩

- Interview with Andrew Castrucci, New York, January 29, 2012. ↩

- Peg Tyre and Jeannette Walls, “Down but Not Out in Soho,” New York, April 24, 1989, 21. ↩

- Homeward Bound meeting minutes, Martha Rosler personal archives, consulted December 2010. ↩

- Martha Rosler, “Fragments of a Metropolitan Viewpoint,” in If You Lived Here: The City in Art, Theory, and Social Activism / A Project by Martha Rosler, ed. Brian Wallis (Seattle: Bay Press, 1991), 38. ↩

- Interviews with Rosler, July 21, 2010, Brooklyn, and Wiley, May 26, 2011, New York. ↩

- Letter from Charles Wright, August 7, 1989, Martha Rosler personal archives. ↩

- Marriott, B3. ↩

- John Jiler, Sleeping with the Mayor: A True Story (St. Paul: Hungry Mind Press, 1997). ↩

- This date is given in the undated Homeward Bound letter sent to members, Martha Rosler personal archives. Though the letter is undated, its description of recent activities suggests a date of between June and December 1989. ↩

- Marriott; see also Michael Marriott, “City Hall Notes; 35 Homeless Protesters Stay Put in ‘Kochville,’” New York Times, June 19, 1988, A25. ↩

- Telephone interview with Bill Batson, February 7, 2012. ↩

- Marriott, “Homeless in Park Sticking to a Cause,” B3. ↩

- Homeward Bound, undated letter to members. ↩

- Interview with Dan Wiley, May 26, 2011, New York. In “Fragments of a Metropolitan Viewpoint,” 43, Rosler thanks DeeDee Halleck (of Paper Tiger Television), Molly Kovel, and Nadja Millner Larsen for providing “soup, bread, and good cheer at the ‘Homeless’ opening, while Emmaus House singers nourished us as well.” Emmaus House is a transitional housing facility. Rosler states that Halleck and the others in fact served a larger meal, drawing inspiration from Gordon Matta-Clark’s restaurant Food, but that the meal was referred to specifically as “soup” within the framework of the show because Homeward Bound wanted to serve soup in the gallery. E-mail correspondence with Martha Rosler, March 8, 2015. ↩

- Audio recordings, Dia Art Foundation archives, consulted January 2011. ↩

- Telephone interview with Batson, February 7, 2012. ↩

- Rosler, “In, Around, and Afterthoughts,” 322. ↩

- Dia had these two images organized with the rest of its slides for If You Lived Here . . . as of 2010, but they have since been misplaced and so cannot be reproduced. The labeling on Dia’s slides for the project suggests, though does not directly confirm, that the two photos of Homeward Bound it had were taken by Slor. However, Rosler points out that the dimensions and style of these two images are less consistent with Slor’s photography and the large-format, wide-angle lenses he was using to make installation shots, than with the 35mm SLR camera with which Rosler was shooting at the time. E-mail correspondence with Martha Rosler, March 6, 2015. The images might also have been taken by Dia assistant Karen Ramspacher, though Ramspacher has no memory of who took them. E-mail correspondence with Ramspacher, March 4, 2015. Or another photographer may have shot them. Slor died in 2008, before I started this research. ↩

- Telephone interview with Gary Garrels, October 14, 2010. ↩

- Telephone interview with Fallon, December 6, 2011. ↩

- Interview with Wiley, May 26, 2011, New York. ↩

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982), 10–11, 92. ↩

- bell hooks, “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” in Picturing Us: African American Identity in Photography, ed. Deborah Willis (New York: New Press, 1994), 43. ↩

- Craig Owens, Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 206. ↩

- Rosler discusses this effect in her essay on Lee Friedlander, where she argues that despite its highly authorial nature, Friedlander’s oeuvre productively disrupts this spontaneity/truth effect. Martha Rosler, “Lee Friedlander, an Exemplary Modern Photographer” (1975), rep. Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975–2003 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 115. ↩

- Rosler, “In, Around, and Afterthoughts,” 186. ↩

- Fax from Rosler to Wright, August 24, 1990, Martha Rosler personal archives. ↩

- Fax from Wright to Rosler, August 29, 1990, Martha Rosler personal archive. ↩