Episode One, 2000

Since the rise of appropriation in American art of the 1980s, the strategy has become so commonplace as to evade continued examination as a unique vein of artistic practice. At the same time, recurrent intellectual property battles around appropriative gestures in contemporary art have threatened its viability, giving rise to CAA’s important report published in February 2015, the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts. This three-part essay on the work of Karl Haendel, an LA-based artist best known for his arrangements of meticulously rendered drawings of found photographic imagery, connects three moments in his early career related to issues of artistic and cultural heritage and power. The first two episodes directly involve knights. Taking Haendel’s work as a point of departure and considering the digital turn, the essay examines how the operations, effects, and reception of appropriation have changed in recent decades and discovers what may be the strategy’s longest-lasting politics of signification.

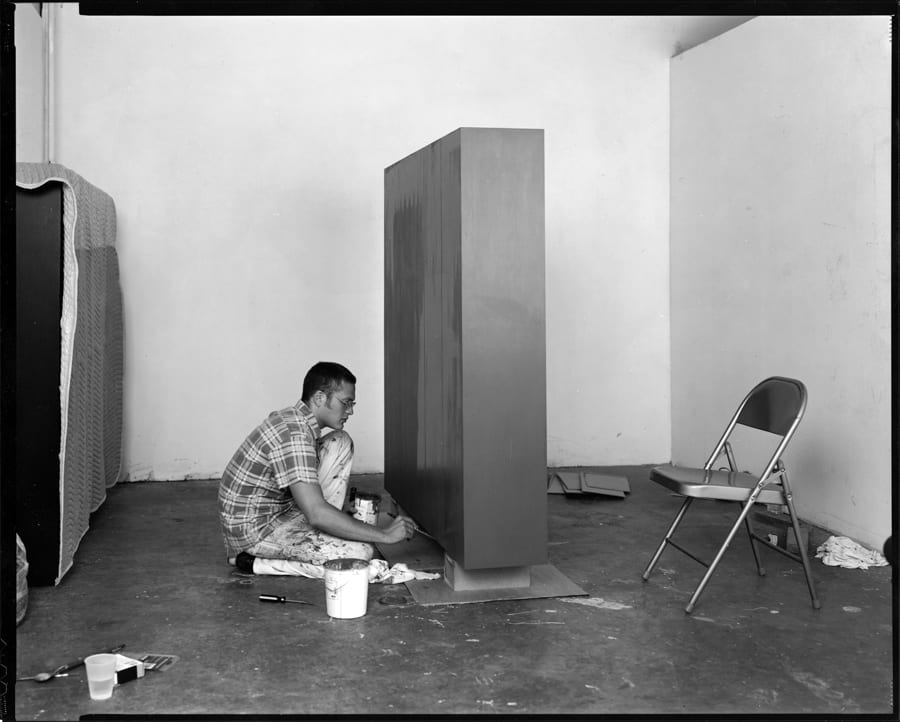

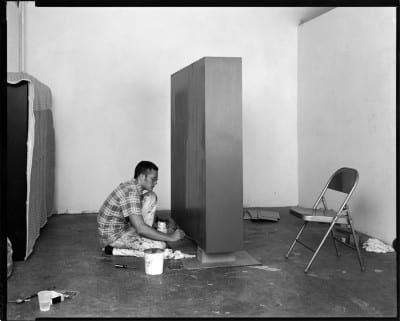

In 2000–1, during his first year of graduate study in the Interdisciplinary Studio program at UCLA headed by Mary Kelly, Karl Haendel made a full-scale replica of Anne Truitt’s 1963 sculpture Knight’s Heritage. His replica was an upright monolith, sixty and one-half inches square on its broadest face and twelve inches deep, constructed from plywood and painted with acrylic paint in three crisply distinguished, monochromatic, vertically oriented sections—maroon, yellow, and black—evoking but not directly copying the heraldic design of the German flag. In addition to Knight’s Heritage he made a replica of Truitt’s Valley Forge, also from 1963 and with similar dimensions, but painted in red quadrangles of varying tones. He gave his reconstruction project the overarching title For/After Anne Truitt. Haendel had never seen either of Truitt’s works in person. But if he had moved to Los Angeles only a year earlier, he could have seen Knight’s Heritage in Truitt’s first solo show in the city, held at the Beverly Hills gallery Grant-Selywn Fine Art in April and May of 2000.

In creating his replica of Knight’s Heritage, Haendel hewed as closely as possible to Truitt’s original in the work’s appearance, materials, and construction. Through his research at Truitt’s New York gallery he knew that the limits of the work’s abutting color planes were materially emphasized by subtle grooves etched into the wooden surface (an effect Haendel achieved with a router) and that Truitt’s colors, despite being bold and unmodulated, were applied brushily in many thin, semi-transparent coats. These are details not evident to the eye in most photographs of the work. Even so, when Haendel finally saw Truitt’s actual sculpture nearly a decade later, years after his own replica had been discarded in his move from UCLA’s graduate studios (it was big, and heavy), Haendel immediately understood that the depth of his grooves had been somewhat off. Did Truitt in fact layer panels on top of a constructed box to create those vertical channels? Haendel couldn’t be sure. In any case, the length and height of Knight’s Heritage actually turned out to be sixty and three-eighths inches, not sixty and one-half as Haendel originally thought.

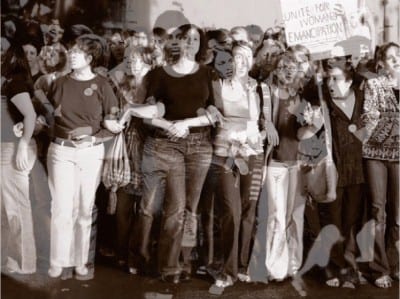

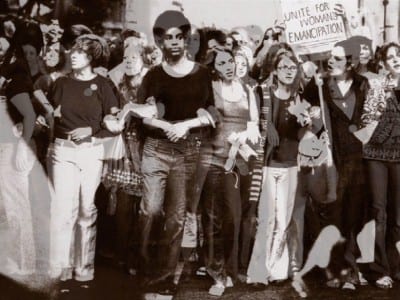

Haendel, a white man born in 1976, came to UCLA via the Whitney Independent Study Program after studying art and semiotics at Brown University. In 2000, when Haendel launched his graduate work with the Truitt project, his professed interest was in politicized, text-based forms of public art. Hans Haacke, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Jenny Holzer, and Barbara Kruger were his heroes in a time when the history of art taught in universities ended more or less with the Pictures Generation. Feminist art and theory were an increasing influence on Haendel, through Kelly and his grad student peer group. For a time, his studio was next door to that of Sharon Hayes, a friend; they participated in the same feminist reading group and curated shows together. On the face of things, Hayes’s practice, centered on the reperformance of historical protest gestures and language, would seem to bear little in common with Haendel’s (typically) object-based work, and yet both artists engage in the replication of extant images and gestures. To imagine their work as part of a shared conversation about appropriating or reperforming signal moments in the history of art and politics illuminates the ways in which appropriation operates differently within the value systems associated with objects and performance, respectively. To copy an artwork (as image or object) is to steal it, whereas repetition is ontologically necessary for a work of performance to persist, and the very act of reperformance is typically coded as being positively motivated by care.

Truitt, a white woman born in 1921, was an American Minimalist sculptor active since the earliest moments of that movement. Her first New York solo exhibition, which included six works similar to Knight’s Heritage, took place at André Emmerich Gallery in April 1963, the same year that Robert Morris and Donald Judd’s Minimalist works first began to be shown. In 2000, when Haendel embarked upon his For/After Anne Truitt project, Truitt was still largely underacknowledged, although her work and its formative role within the development of Minimalism and its discourse were about to come into wider appreciation through the publication of James Meyer’s study, Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties1. Meyer’s book reclaims Truitt as a crucial progenitor of Minimalist sculpture circa 1963 alongside Morris and Judd, and indeed it was Meyer’s scholarship, which included a richly illustrated Phaidon volume on Minimalism published in 2000, that helped motivate Haendel’s interest in Truitt’s work and its relation to canonical understandings and histories of 1960s art.2 In 2009, Kristen Hileman of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC, mounted the largest Truitt exhibition since the 1973–74 mid-career retrospective that traveled between the Whitney Museum in New York and the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC.3 But Truitt never saw her Hirschhorn show—it took place five years after her death.

As both a sculptor working in a modernist idiom in the 1960s and a woman, Truitt was victim to both aesthetic and gender double standards. Her work looked like Minimalist sculpture, but, according to Judd, it didn’t have the right literalist intentions behind it. Reviewing her April 1963 Emmerich show for Arts Magazine, Judd was caustic and dismissive: “There are a number of boxes and columns, both simple and combined, in this exhibition, and a large slab. The colors are dark reds, browns and grays, very much like Ad Reinhardt’s color. The work looks serious without being so. The partitioning of the colors on the boxes is merely that, and the arrangement of the boxes is as thoughtless as the tombstones which they resemble.”4 In retrospect, Judd’s judgments seem defensive and proprietary, for while he and Morris had recently shown their own Minimalist sculpture in the group exhibition New Work: Part 1 at Green Gallery in January, they wouldn’t have major solo shows there until later that year, in October (Morris) and December (Judd). As for Morris, Truitt became acquainted with his version of Minimalist sculpture first through magazines, and in spring 1965 she requested a studio visit. Encountering both artist and his work in Morris’s New York loft, she found both disappointing. The objects were indifferent, cold, too theoretical, and poorly made, their even gray color resolutely unmoving. Plus, she said, “if you’d kicked them they would have fallen apart.”5

The modernist critics who did celebrate Truitt in this moment turned out to be on the wrong side of art history. Moreover, their support of her work was often undermined by distracting asides about her identity as a woman and—seemingly worse—a mother. In a 1968 profile of Truitt by Clement Greenberg published in Vogue, Greenberg laments (sort of), “She remains less known than she should be as a radical innovator. She certainly does not ‘belong.’ But then how could a housewife, with three small children, living in Washington belong? How could such a person fit the rôle of pioneer of far-out art?”6 It was true that Truitt lived in DC, but so did Kenneth Noland and the rest of the so-called Washington Color School. Noland was a friend and interlocutor who introduced Truitt to Greenberg. It was those two men, in fact, plus the MoMA curator William Rubin—the Ken, Clem, and Bill to whom Truitt refers to in her diary of 1963—who were behind what Judd saw as the “thoughtless” arrangement of her show at Emmerich’s gallery. And Emmerich himself tried to convince Truitt to allow him to drop her forename from the show’s ads.

Truitt’s work was problematically situated between the paradigms of modernist art and its preoccupation with optical address, and the radically new, postmodern, literalist orientation of Judd and Morris’s Minimalism. Her works were neither exuberant, transcendent, autographic expressions unburdened by worldly associations, nor quasi-anonymous, desubjectivized gestalts. Truitt’s sculptures had obscure referents which the artist openly related to her own biography. As Meyer argues, Truitt’s sculptures are allusive, associative metonyms of her experiences and memories: “Each sculpture is the residue of a memory or chain of memories triggered during its completion.”7 The connotations of these personal allegories in object form could shift over time for both artist and viewer. An early example of what I would call Truitt’s unique mode of “metonymic abstraction” is her early work First, 1961. It appears to be a segment of a white picket fence, but it is also clearly useless for that purpose, being only two-and-a-half stakes in length. The thing evokes a generic but also specific kind or type of fence. Meyer writes, “First is not one fence but the token of all of the fences of Easton [Maryland, the artist’s birthplace] that Truitt could remember from the distant past.”8 First thus proposes a model of abstraction in which the abstract becomes a synonym for the generic, a model in which form—for Truitt, shape in concert with color—becomes typological, stripped of all but its most essential, characteristic elements in order not to transcend the world but to relate ever more capaciously to it. First: not one fence but the token of all she could remember. Truitt’s work would only become more abstract and allusive from there. A series of seven quasi-fences followed, standing hexahedrons of differing widths with slats united, delineated only by vertical grooves of the same kind that would appear in Knight’s Heritage.

What happens when we read the supposedly modernist work of Truitt through the lens of Haendel as a second-generation postmodernist? Given the allusive, allegorical quality of Truitt’s metonymic abstraction, could it be that Haendel was drawn to her work for the ways in which it seems surprisingly more postmodern in its operations than that of Judd or Morris, as the allegorical has become one of the defining terms of our understanding of postmodernism? If such a claim is less than convincing, we may consider instead the timing of Haendel’s (re)turn to Truitt at the turn of the twenty-first century, a moment that saw the first reconsiderations of 1980s appropriation art and its by-then canonical theorizations—a moment when critics began to trouble the earliest accounts of that work as being manifestly critical of conventional notions of artistic authorship and subjectivity. In 2004, Johanna Burton wrote of the “overdetermined exclusions of race, gender, and sexuality” made by critics such as Douglas Crimp and Craig Owens in their analyses of work by Sherrie Levine, Barbara Kruger, Laurie Anderson, and others. These exclusions were made “in the name of a properly critical definition of appropriation” that repressed questions of individual identity and subjectivity in favor of reading the work in terms of a project of critical deconstruction—of the museum, the media, and the very structures and processes of signification and representation that take place within them.9 But, Burton argues, if we consider the ways in which appropriative gestures are driven by the individual investments of subjectivity and identity, we can begin to see the projects of this very same generation of artists not only in terms of critical deconstruction, but as constructive projects that seek to build a kind of “connective tissue, mediating the flow of collective and individual histories and providing the opportunity to insert oneself, however promiscuously, within them.”10 (Indeed, Crimp and Owens would come to recognize and revise their original claims about appropriation art to this effect.)11 Writing in 2007, Jan Verwoert described contemporary modes of appropriation similarly, as gestures of mining “unresolved moments of latent presence” and “staging object, images or allegories that invoke the ghosts of unclosed histories” in order to free culture “from the grip of its dominant logic and put it at the disposal of a different use.” The “re-use of a dead commodity fetish” becomes rather an “invocation of something that lives through time.”12 To turn to the words of an artist, Levine has argued that Warhol “chooses images that he loves”; of her own work she has said it only accrues meaning “in relationship to everyone else’s project.” “I’m not trying to supplant anything,” Levine insists, “my work is in addition.”13 Accordingly, revised accounts of appropriation art have begun to attend in finer detail to the identity-driven, subjective motivations of appropriative gestures, such that we can begin to understand them as productively redrawing lines of historical relation rather than automatically amounting to the undermining of authorship or authenticity. Instead of a teleological, vertically hierarchical, Oedipal notion of historical time, acts of appropriation may imagine time as lateral and constellational. Repetition is not always an act of erasure or overwriting past artistic gestures. It may be a means of deliberate and sympathetic alignment, of establishing one’s elective affinities.

In June 2012, The Art Bulletin’s “Notes from the Field” section focused on appropriation, and the contributing authors provided a remarkably broad range of art-historical meditations on the meaning of that term. In Saloni Mathur’s piece, she asks, “Does appropriation somehow belong to these discussions that emerged during the 1980s and 1990s, to postmodernism, poststructuralism, postcolonialism, and deconstruction? Has the concept reached a theoretical impasse or lost its edge as an analytical tool?”14 Clearly the answer to both is no. We have only too recently begun to appreciate the full range of appropriation’s various modes or affects: critique, disrespect, and envy, but also admiration, affiliation, identification, possessiveness, desire, and lust. Leo Steinberg’s 1978 essay “The Glorious Company,” written for the catalogue of Art About Art, a Whitney Museum survey of postwar art that takes past art as its subject matter, had already seized upon these varied motivations.15 Almost completely forgotten within the literature of 1980s art, Steinberg’s essay appeared at virtually the same moment as Crimp’s famed Pictures exhibition (Artists Space, New York, 1977), which inaugurated the canonical appropriation-as-critique narrative. In Steinberg’s view, an artist appropriates from “an overplus of generosity” “with reference and affection,” and through this act can invest the appropriated work with renewed relevance, can actualize its potentialities, and can “clear cobwebs away and impart freshness to things that were moldering in neglect or, what is worse, had grown banal through false familiarity. By altering their environment, a latter-day artist can lend moribund images a new lease on life.”16

It could be said that with For/After Anne Truitt, Haendel was simply doing what any young artist conventionally does in art school—make copies of things. But that model of art pedagogy is an old, academic one that no longer applies to advanced graduate study in the United States, especially within UCLA’s conceptually oriented program. So why would Haendel embark on an experiment to copy, appropriate, or redo Truitt?

With For/After Anne Truitt, Haendel was confronting head-on, at one of the earliest moments of his career, the anxiety of influence felt by creative practitioners most famously articulated by Harold Bloom. Haendel was interested in the radical politics of 1960s art, the art of Kelly’s generation, but also felt that that time was impossibly past. In Haendel’s millennial, post-postmodernist moment, the “exhaustions of being a latecomer” were felt acutely.17 His gesture of copying Truitt might be seen as an attempt at control, possession, and art-historical supercession. To appropriate is to take something and make it one’s own. The etymology of the word “plagiarism” points us to the figure of the kidnapper or seducer. There is, it must be admitted, a problematic dynamic of identity politics to Haendel’s gesture. A young male artist co-opts the work of a supposedly more established female artist who is nevertheless underacknowledged, maybe even somewhat forgotten within art history. If Haendel remakes an obscure Truitt sculpture called Knight’s Heritage, will anyone even recognize it as referring to an original by Truitt? And this in the context of a contemporary art world obsessed with youth—we now have recurring exhibitions focused on artists under the age of thirty—in which MFA programs disproportionately churn out ambitious white male artists whose work is promoted and advanced on cultural, social, and economic terms by art collectors who understand their art objects as an asset class within a larger portfolio of wealth. It is not uncommon to encounter art collectors prowling the halls of UCLA MFA open studio events.

Despite these very real cultural dynamics, it still seems more accurate to me to understand Haendel’s gesture as counter-canonical, made by a young male artist who wondered if a young male artist just starting art school could work in a feminist mode. Appropriation is actually the wrong word for Haendel’s project, if appropriation means to take something and make it one’s own. For/After Anne Truitt was a performative yet object-based homage, an act of remembrance labored over through material means. It was Haendel’s performance of fidelity to Truitt and her work, a woman producing art in the historical moment of second-wave feminism not typically seen as a feminist artist. That historical moment also not coincidentally forms the groove along which one of Haendel’s mentors, Kelly, has guided much of her practice, interested in acts of historical fidelity and self-alignment.18 Haendel’s gesture was that of an artist who wanted to think about and align himself with possible art-historical “mothers” as he worked through the very real loss of his own mother to cancer. Equally important, it was the gesture of an artist interested in exploring alternative modes of masculinity. In addition to Kelly, Paul McCarthy and Charles Ray were important figures in Haendel’s graduate experience, with McCarthy in particular encouraging Haendel to adopt a self-critical perspective on his own male privilege. As Haendel recounts, “Basically, there is something a bit perverse and ‘wrong’ in making these Truitt copies, and Paul taught me that going to the place that is perverse can be powerful and generative.”19 While we should remain skeptical of the ambition and ability (never mind the necessity) of a young male artist to deliver a seasoned female artist of an older generation to greater art historical prominence, we can also recognize the aesthetic and ethical value of Haendel’s embodied act of unscripted remembrance and alignment. Haendel didn’t simply “take” Truitt’s work: he rebuilt it from scratch and enabled it appear again, to command space within his own present, and to occupy his time and labor during crucial years of his own artistic development. Having never seen the work and (re)constructing it as true to form as possible, for Haendel “his” Knight’s Heritage occupied the positions of both original and copy. It was an object that suggested, or so Haendel hoped, that one could have an authentic experience of a copy.20

From Truitt’s Daybook, November 9, 1974:

Certain concepts seem to choose to come into existence. For example, in 1962 I saw clearly, walked around in my mind and decided not to make, a 6’ X 6’ X 6’ black sculpture. I can see it now perfectly plainly in the loft room of my Twining Court studio, just to the right of the entrance and illuminated from the hay-loft door beyond. A few years later, I read that Tony Smith had made exactly this sculpture; and somewhat later I saw a picture of it. I have never met Tony Smith, nor has he met me. On the evidence, I can only assume that we caught the same concept.21

From Truitt’s Daybook, March 6, 1975:

Matter is stubborn. Only dogged effort brings a concept into an arena in which it can demand the serious attention we give a challenge to our own physical selves. . . . The ideas in my head are invariably more radiant than what is under my hand. But something puritanical and tough in me won’t take that fence. The poem has to be written, the painting painted, the sculpture wrought. The beds have to be made, the food cooked, the dishes done, the clothes washed and ironed. Life just seems to me irremediably about coping with the physical.22

In closing out this first episode in Heandel’s early career, I want to remember the gendered associations of copying. As Hillel Schwartz makes plain in his encyclopedic cultural history, The Culture of the Copy, since the nineteenth century the labor of copying has largely been the province of women.23 Copyists, copy clerks, stenographers, and typists have historically been women. Women were also the earliest collagists, appropriating the images of others and creating from them new image worlds. Linked as well to the labor of copying, women have been associated with activities of preservation, restoration, and revival as decorators, seamstresses, aestheticians, therapists, social workers, and curators. Then there is the labor of women at home. Across private and public spheres, domestic and professional settings, women’s labor has typically been cyclical, repetitive, additive, and reproductive—not “original.” Recall the words of Levine, who had internalized this social fact: “I’m not trying to supplant anything; my work is in addition.”24

Haendel’s project of copying Truitt’s work involved some of the planning, sketching, diagramming, and design typically associated with the making of Minimalist sculpture. But Haendel did not delegate that labor to industry. He did it himself, and the bulk of it consisted of laying down the paint, layer after layer. Haendel believed that through his labors he came to know every inch of those Truitt sculptures. His labor of construction and hand-painting prefigured his present commitment to the labor of drawing found images in a photo-realistic style, the labor of methodically reproducing found images through tracing them as they are projected at large scale onto the walls of his studio. Seen through the lens of cultural history, Haendel’s practice—now a labored shared with studio assistants—is a form of work historically ascribed to women.

Although Truitt was alive at the time that Haendel made his reconstructions, of course she never knew of them. The product of an experimental student exercise, the sculptures never left Haendel’s studio and were destroyed before he left UCLA. All that remains of them are a few photographs, including a process image taken by Haendel’s classmate, Florian Maier-Aichen. It shows Haendel crouched low to the ground next to one of the sculptures, delicately applying to it coats of paint. On the other side of it sits an unoccupied metal folding chair. Much of the labor that went into those sculptures, as we know from the accounts of both Anne and Karl, is the labor of sitting and waiting for paint to dry.

To read Nate Harrison’s response to this essay, click here.

Natilee Harren is assistant professor of contemporary art history and critical studies at the University of Houston School of Art. Her research engages experimental, interdisciplinary practices after 1960, with particular emphasis on intermedia art and theories of translation between artistic mediums and disciplines; the role of notations, scores, and diagrams in conceptual and performative art practices; institutional critique; social practice; and theories of appropriation. Her current book project, “Objects without Object: Fluxus and the Notational Neo-Avant-Garde,” examines the work of the international, neo-avant-garde Fluxus collective amid transformations of the art object wrought by score-based practices of the 1960s and the epochal shift from modernism to postmodernism. Harren is also coeditor of a critical anthology, forthcoming from the Getty Research Institute, which surveys and theorizes a range of twentieth-century experimental notations from the fields of performance art, dance, literature, and music within a media-rich digital platform. Her essays and criticism have appeared or are forthcoming in Art Journal and Getty Research Journal, among other publications, and she has been a regular contributor to Artforum since 2009.

- James Meyer, Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001) ↩

- James Meyer, ed., Minimalism (New York: Phaidon, 2000). ↩

- Kristen Hileman, et. al., Anne Truitt: Perception and Reflection (Washington, DC: Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, 2009). ↩

- Donald Judd, “In the Galleries,” Arts Magazine, April 1963, rep. Judd, Complete Writings 1959–1975 (Halifax: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 2005), 85. ↩

- Truitt quoted in Meyer, Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties, 80. ↩

- Clement Greenberg, “Changer,” Vogue, May 1968, 284. ↩

- Meyer, Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties, 72. This central conceit of Truitt’s practice is taken up in Miguel de Baca’s recently published study, Memory Work: Anne Truitt and Sculpture (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2015). ↩

- Ibid., 70. ↩

- Johanna Burton, “Subject to Revision,” Artforum, October 2004, 260. The original texts to which Burton refers are Douglas Crimp, “Appropriating Appropriation,” in Image Scavengers: Photography (Philadelphia: Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, 1982), rep. Crimp, On the Museum’s Ruins (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), 126–37; and Craig Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism (Part 2),” October 13 (Summer 1980): 58–80. ↩

- Ibid., 262. ↩

- Douglas Crimp, “Photographs at the End of Modernism,” in On the Museum’s Ruins, 2–31; and Craig Owens, “The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism,” in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Port Townsend, WA: Bay Press, 1983), 57–77, rep. Owens, Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Culture (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992), 166–90. ↩

- Jan Verwoert, “Living with Ghosts: From Appropriation to Invocation in Contemporary Art,” Art & Research 1, no. 2 (Summer 2007): 3, 7 at www.artandresearch.org.uk/v1n2/verwoert.html, accessed July 21, 2015. ↩

- Levine quoted in Jeanne Siegel, “After Sherrie Levine,” Arts Magazine, June 1985, rep.Siegel, ed., Art Talk: The Early 80s (New York: Da Capo, 1988), 253–4. ↩

- Saloni Mathur, “Notes from the Field: Appropriation: Back Then, in Between, and Today,” The Art Bulletin, 94, no. 2 (June 2012): 182. Ursula Frohne, in her contribution to the issue, helpfully reminds us of Michael Baxandall and Mieke Bal’s writings on artistic influence and aesthetic returns. See Michael Baxandall, Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), esp. 18–19, and Mieke Bal, Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). Additionally, the resurgent interest in the work of Sturtevant signals a continuing need to historicize and theorize the existence and meaning of appropriative strategies in contemporary art. ↩

- Leo Steinberg, “The Glorious Company,” in Art About Art ed. Jean Lipman and Richard Marshall, ex cat (New York: Dutton/Whitney Museum of American Art, 1978), 8–31. ↩

- Ibid., 25, 28. It is an illuminating exercise to list all the synonyms that Steinberg, one of art history’s most vivid writers, uses in this essay to refer to acts of appropriation and their objects: derivation, took, steal, emulated, lifting, purloined, filched, borrowing, supercession, employ, foraging, exploit, avail, recycling, recirculation, transposed, transcription, arrogating, inheritance, copyist, revision, importable, translation, loot, quotations, borrowed, immigrant presence, rehearsal, transmitted, recruited, clipped, spliced, tokens of prefabrication, readymades, inspired, influence, cannibalize, plagiarism, stealing, borrowing, wandering motifs, quoting, importation, snatches, giving, lending, imparting, spiritual intercourse, imitation, gathering, depredation, assimilating, being fertilized, impregnation, contracting infection, trespass, echoing, join, piracy, mock, parody, reviving. ↩

- Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 12. ↩

- Such has been beautifully argued by Rosalyn Deutsche in her essay, “Not Forgetting: Mary Kelly’s Love Songs,” Grey Room 24 (Summer 2006): 26–37. ↩

- Karl Haendel, e-mail to the author, July 15, 2015. ↩

- As Cordula Grewe writes in her contribution to the The Art Bulletin discussion about appropriation: “To copy becomes an escape from the burning feeling of belatedness by seizing on that very belatedness, and this escape opens up to an unexpected free space, a space in which authenticity emerges from the conscious embrace of its lack.” Grewe, “Notes from the Field: Appropriation: Back Then, in Between, and Today,” The Art Bulletin, 94, no. 2 (June 2012): 175. ↩

- Anne Truitt, Daybook: The Journal of an Artist (New York: Scribner, 1982), 94. ↩

- Ibid., 146. ↩

- Hillel Schwartz, The Culture of the Copy: Striking Likenesses, Unreasonable Facsimiles (Brooklyn: Zone, 1996). ↩

- Levine quoted in Siegel, “After Sherrie Levine,” 254. ↩