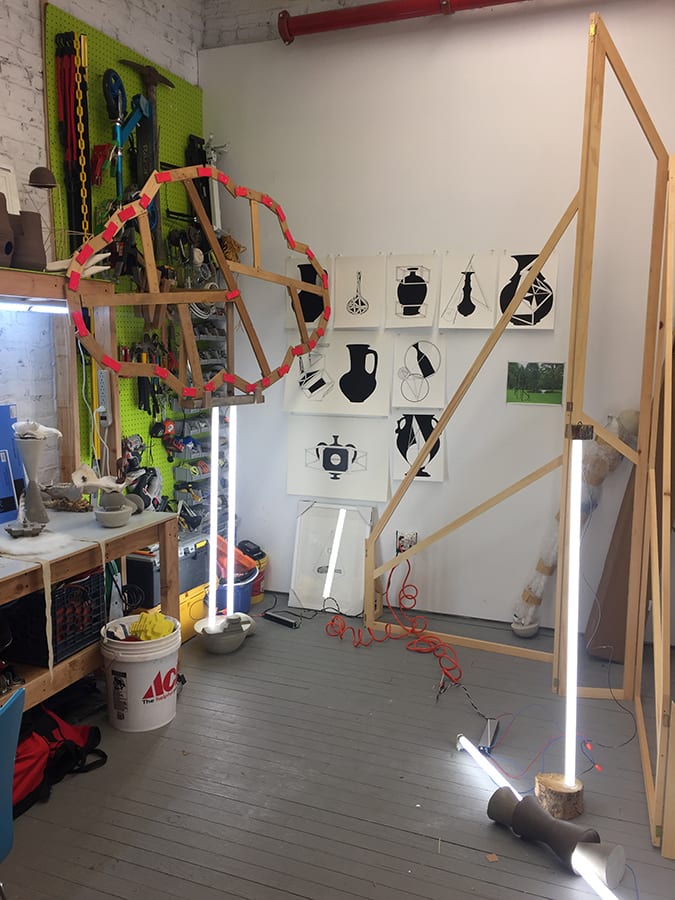

I recently dropped by Chad Stayrook’s studio, which is in the back of Present Company, the artist-run gallery that he cofounded and has been codirector of since 2010. In his space, he has many new projects in progress for shows over the next two years. Since Chad often does artist residencies at varying levels of solitude, working in a more permanent studio space tends to be a challenge in which he finds himself mixing media, reorganizing and altering his practice to stave off claustrophobia. Chad’s newest works, ranging from sneak previews of video pieces to small-scale mixed-media sculptures, crowd his studio as if each were a sketch drawn on top of the next, and elbowing each other off the page. In the studio, they seem to combine into an installation of their own making, climbing on top of and around each other. This might be how Chad’s work is best experienced: walking into something that has all the formal visual elements that I understand but are put together in such a way as to create an utterly lovely mystery. In the following conversation, Chad and I discuss these new works, as well as his experiences at artist residencies.

—Caitlin Masley-Charlet

Caitlin Masley-Charlet: How do you sustain your art practice?

Chad Stayrook: Work, work, work. After grad school I spent about nine years in arts administration and nonprofit work. It was demanding and underpaid, and while it kept me involved in the arts on a day-to-day basis, it took a toll on my art practice. For the last three years I’ve been doing commercial painting jobs. They pay well, and I can usually get by working just one to two weeks a month. This has opened up my time to work in the studio and participate in residencies.

Masley-Charlet: What about sustaining the creative part of your practice? How has it developed in the years since you graduated?

Stayrook: I codirect an artist-run gallery called Present Company that keeps me constantly immersed in other artists’ work and ideas. I keep correspondence with my collaborator Julia Oldham, looking for ways in which our project, Really Large Numbers, can create work remotely. This in particular is nice because it allows for an outlet outside my own practice and often outside the kinds of work I would otherwise be making on my own.

Since graduating in 2004, I’ve learned what kinds of things I can do that allow for more time to be a practicing artist. My nine-to-five gig killed my creativity. The part-time nonprofit gallery director job that I took afterwards ended up being more like full-time and left barely any room for my own practice. The commercial painting work has given me flexibility, and I’ve found that non-art-related work makes focusing on my art practice a lot easier. Nowadays it’s all about time management—I still have a lot to learn in that department. ‘Work’ work needs its own time and needs to be left at work when I’m done. If I’m not careful the gallery can start to take over my time, but I’ve gotten better about managing that in recent months.

Masley-Charlet: What motivated you to apply to your first artist residency, and did this coincide with the end of graduate school?

Stayrook: The first residency I did was at the Tin Shop, in Breckenridge, Colorado, in 2009. Since then, I’ve been able to do at least one residency each year, and residencies have become a crucial part of my art practice. I thrive on new environments to respond to in my work, and residencies allow for geographic and sociological diversity. I’m trying to be better about this, but I’ve never been a big studio artist. I like traveling and making work in new places where I have to use my wits to find resources for the work that the place inspires. In my studio, I tend to get bored or sidetracked. An unrestricted structure and limited time frame makes me extremely productive. What motivated me to apply for residencies was seeing my peers in school come back from them and share what they had done. It seemed like something artists should be doing as part of their professional careers. I’m sure I would have gotten around to it regardless, but there was definitely an element of peer pressure that convinced me to apply to residencies.

Masley-Charlet: After your experience at Tin Shop, how did you feel about residencies, and what did you look for when applying to the next ones?

Stayrook: The Tin Shop residency made me realize that there were opportunities out there besides the mainstream ones that all artists are focusing on and applying to. It especially made me interested in residencies in far-flung places with environments different from my home base in New York.

Masley-Charlet: What was your next residency, and why did you choose it—was it the stipend, facilities, or prestige?

Stayrook: One of the next residencies I did was The Arctic Circle residency in Svalbard, Norway. As soon as I saw it, I knew I had to do it. It’s one of the only residencies I’ve applied for that I was completely adamant about getting. It was just so in line with my art practice. That was my main motivation for applying, and I’ll admit that at the time it was so unique (I was part of the second expedition of the program) that there was an element of bragging rights, if not prestige. It didn’t provide much in the way of financial support and cost quite a bit to participate in, but it was a weird enough opportunity that it was easy to raise funds and apply to grants that would support it.

Masley-Charlet: What interested you about the Guttenberg Arts residency?

Stayrook: I was interested in a residency that offered ceramics facilities, so that was a big draw. It’s also rare to find art opportunities in the United States that give as generous a stipend as Guttenberg. The stipend helped in allowing me a little more flexibility with having to work and with getting materials for experimenting. The ability to have both a solo show and a group show is great, as is the monthly access to visiting critics.

Masley-Charlet: Is access to the visiting critics important because of the potential for exhibitions, the need for artistic and academic dialogue, or something else? What has changed in your process since you’ve been there?

Stayrook: The access to visiting critics and curators at residencies is certainly a bonus, but I find the visits can be a little intimidating as you are discussing new ideas and work-in-progress that hasn’t been entirely resolved. I prefer to set up studio visits on my own terms in my own studio as I have more control over what I’m sharing. That said, residencies are great networking opportunities, and meeting critics during them makes it much easier to follow up for visits in the future. My practice has always revolved around upcoming exhibitions or has been specific to a certain space that different residencies offered, rather than in the studio. That has completely changed after my residency at Guttenberg Arts. I’ve been making work regardless of where or if it will show. It’s been much more experimental and I’m happy with the results.

Masley-Charlet: What is the importance of an artistic community for you?

Stayrook: Alongside my art practice I run a gallery that does about six to eight shows a year, and many special events. It’s a lot of extra work, but I do it because it creates a space for my peers to come together. Access to other artists in a social atmosphere is really important to me. Having the gallery helps me meet new artists and provide career support, which feels really good. Art residencies are what I look to for that kind of support with my own work. The gallery work is more of a selfless pursuit, but at residencies it gets to be a little more about me. Outside of art school, residencies are one of the best places to develop your community of peers in the art world.

Masley-Charlet: What have done since you’ve left Guttenberg Arts and what are looking to do now?

Stayrook: Since leaving Guttenberg Arts, I’ve done three more residencies: Coast Time in Oregon, Wave Hill Winter Workspace in New York, and Teton Art Lab in Wyoming. I’ve been in a quite a few shows and screenings, and I’ve finally organized my tiny, 110 square-foot studio into a space I can actually make work in. In April 2017, I was in a two-person show at Neon Heater Gallery in Findlay, Ohio, with Julia Oldham. For the exhibition, I made a new, large installation of the ten space probes that are the furthest man-made objects from Earth. In June, Really Large Numbers completed Birth of a Star, a huge installation for the exhibition Light Years Away at Index Art Center in Newark, New Jersey. This installation will travel to Rockville, Maryland in 2018. I have most recently completed a public sculpture for NYC DOT’s Community Commissions program in West Farms Plaza in the Bronx. The sculpture, a twenty-four-foot-tall paper airplane perched on its back, is my largest artwork to date.

Masley-Charlet: Have you met anyone during a residency that has had a big influence on you, or someone you’ve kept in touch with?

Stayrook: I have met a lot of influential people at residencies and do my best to keep up correspondence. I developed some long-term professional relationships from The Arctic Circle Program, in particular. The director of that program is starting a sailing-based residency, and I’ve been invited for a voyage in 2018, along with with eight other Arctic alumni. I’ve made at least one (if not more) close friendship from every residency I’ve participated in. I especially like when I’m able to introduce artists I’ve met to my partners at Present Company to consider for exhibitions in our space.

Masley-Charlet: How did Present Company develop, and why did you and your cofounders feel the need to participate in the larger art community?

Stayrook: It’s most important for me that Present Company keeps me connected to other artists and provides an outlet to give back, in a sense. Present Company was founded by Brian Balderston, Jose Ruiz, and me. Initially, we were looking for a space that we could rent as an incubator for both artistic and entrepreneurial ideas. We ended up finding a big space at a great price in Williamsburg and had to put on events to support the rent. The gallery grew out of that. At first we weren’t thinking of long-term programs—we were just putting together events that combined art, music, and performance so we could run a speakeasy bar and raise money to pay the rent. After five months of this, we went on a retreat upstate and made good food, drank a lot, listened to inspirational podcasts, smoked weed, watched Dune, and ended up coming up with a year’s worth of programming. That was really the beginning of the gallery.

Once we had a program in place we got asked to do a lot of other things, including art fairs. Then we lost our space and were floating, doing a couple of pop-up exhibitions and art fairs before finally finding and negotiating our current lease on Johnson Avenue. Once we got settled there and had a few exhibitions under our belt, we brought on a fourth partner, Vince Contarino, to help round out our programming. Vince has this incredible knack for being everywhere and at everything in the art world. He’s also organized in a way we only ever dreamed to be at the beginning. He’s been an awesome addition to the team. More than anything, Present Company is a connection to the art community. That’s the reason for the name—whatever we are all involved in is our Present Company.

Masley-Charlet: Can we talk about failure? Are residencies a safe place to fail?

Stayrook: I think it’s up to the artist to be okay with failure. I felt a certain amount of intimidation at my most recent residency, Teton Art Lab, when talking to the director about epic projects done by past residents. There will always be artists or projects that stand out in a given situation that are worthy of stories over beers and sometimes, I get caught up in wanting to be one of those memorable artists. It took me a moment to be fine with the idea that I was playing with completely new materials and making new work that was hard for me to talk about or explain, even though it was a direct result of that particular opportunity. But a lot of that pressure I was feeling was self imposed. I think that’s the case with most residencies. If you are thinking and working, you are fulfilling your end of the bargain. It can be hard for me to accept that.

Chad Stayrook is a living and breathing artist based in Brooklyn, New York. His work has been shown around the world, across the country, and right here at home (New York City). Stayrook has all the proper credentials and has been verified and fact checked in several well known and lesser known publications. Notable exhibitions include Light Years Away at Index Art Center, Newark, New Jersey; The Impossible Lightness of Being (solo exhibition) at Guttenberg Arts, Guttenberg, New Jersey; 27 Below at De Fabriek, Eindhoven, Netherlands; Peekskill Project V and VI at Hudson Valley Center for Contemporary Art, Peekskill, New York; Homecoming at BRIC, Brooklyn; N.A.D.A video lounge, Miami, Florida; The search for an unattainable beast… (solo exhibition) at Romer Young Gallery, San Francisco, California; Invisible Empire: Undefined Spaces at Van Abbe Museum of Contemporary Art, Eindhoven, Netherlands; and the 2009 Incheon Artists Biennial, Incheon, South Korea, among others. Stayrook has been artist-in-residence at residencies such as Teton ArtLab, The Arctic Circle, Coast Time, iPark, Lower East Side Studio Program (AAI), Wave Hill Winter Workspace, and LMCC Swing Space. A romantic at heart, Stayrook tirelessly pursues his passion for art across many avenues including cofounding/directing an artist-run space, Present Company, in Brooklyn, and collaborating as Really Large Numbers with Julia Oldham. Stayrook’s work is represented by Romer Young Gallery in San Francisco.

Caitlin Masley-Charlet is a Brooklyn-based visual artist working in drawing, installation, and sculpture, and the deputy director of Guttenberg Arts in Guttenberg, New Jersey. She holds an MFA from the University of Arizona and an MS in design and urban ecology from Parsons/The New School. Her work has been exhibited in group shows at MoMA/PS1, Long Island City, New York; Center for Built Environment, Berkeley, California; and Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York. She has had site-specific solo exhibitions at McColl Center for Contemporary Art, Charlotte, North Carolina; Islip Museum, East Islip, New York; Urban Institute of Contemporary Art, Grand Rapids, Michigan; HVcc Foundation, Troy, New York; Kingston Museum of Contemporary Art, Kingston, New York; and the HDLU Museum, Zagreb, Croatia. Masley-Charlet is also the founder of studioMAPstudioSWAP, which is part of the Parsons/DESIS Lab/CSI Incubator program.