The following essay by John Engelbrecht is part of “Beyond Survival: Public Support for the Arts and Humanities,” a call for reflections on and provocation about the precarious state of arts funding after decades of neoliberal economics and the long culture wars.

In my role as the director of a small (tiny, really) Midwest arts nonprofit, I have accidentally inherited a role of perceived power in our town’s little arts sphere. The slight power I speak of: I sometimes get the opportunity to invite artists to participate in projects; to select artists to show work in our gallery; or build a project with someone else’s usually small budget that I most often cobbled together for them from the state or one of its universities. Sometimes I get paid for this work, but usually I do not. My power is pretty much limited to connecting emerging artists to small stipends and “professionalization” opportunities. I am occasionally recognized as “a community builder/leader” and then invited to do more unpaid cultural work. My role is part-time, and I supplement a living through adjunct teaching which, when combined with my directorship contract and workload, makes for an annual salary that comes in well under the federal minimum wage. So when I am asked to talk about scarcity and competitiveness in the art institutions I know, I am doing so from a position that glows almost radioactively with that scarcity. I am writing today with a pile of other things I should probably be doing stacking up, so as to make these scattered ends meet. I voice this embarrassingly, as a precursor not to pull pity or pose as a charitable saint, only to set the stage for my perspective when it comes to “financial tides” in the arts.

The arts sphere I know is one where ends are not quite meeting but the drive to stay the course and make something new happen is still alive. We have heard these types of things described as “passion projects.” I identify as an artist before organizer/director/teacher. I posit myself, daily, as an artist, even if it has been years since I have had any sort of consistent studio time, because this title signifies not only passion, but contrariness, the only way I can make sense of the world. It is this identification that has doomed me to serve as a buffer for the arts and quite literally: my contracted paycheck only comes through once all other line items have been paid. I will take the brunt (or credit card debt) for budgets/donors/projects not balancing out this month, in exchange for the potentials of some new, whatever next Potential Cultural Form. I posit myself, daily, as an artist because I live to see something new, to entertain some new prospect or challenge, regardless of which way (red or blue, green, black?) the state funding falls. I posit myself as an artist because I am against the world as it is and (thank the Dadaists?) artist is the only title that simply, but fully embodies that.

I often imagine the end of the world, the collapse of contemporary, political society. I think of what transferable skills art has given me to stay alive in that alternative era. I think competitiveness and scarcity may mean something else then: precarity a more austere, daily thing instead of an abstract, seasonal one. But then, even then, I cannot imagine not identifying as an artist and seeing the creative challenge and joy in that doom. And from this dark place, we act and converse with our glowing screens and various levels of bureaucratized, institutional backing. Ultimately we only have what we have always had: intimacy in our proximity to kindred others.

Here’s to the people, with whatever power they have to use, to foster that intimacy, with or without an art world. Here’s to an abundance of that intimacy, in local gatherings, more exchanges with authentic people, and communications that cut through the spectacle. Here’s to remembering the falseness of the scarcity narrative, once we take capital out of the equation.

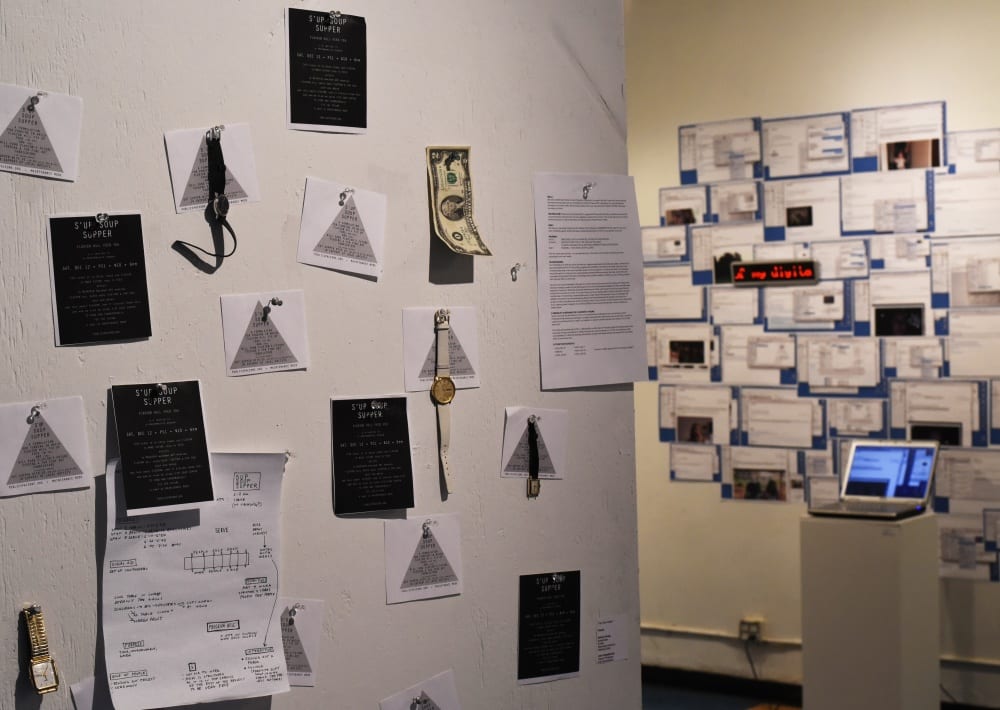

John Engelbrecht is director of Public Space One (PS1), an alternative arts space in Iowa City, Iowa. Countless local, national, and international exhibitions have happened in his tenure at PS1 along with a nearly daily program of performances, workshops, residencies and other (if succinctly indescribable) events.

The next response in the Precarity and Potential chapter is “Generation Wipeout” by Kirsten Galvin and Christina M. Spiker.