In our recent response to the “Beyond Survival” call on Art Journal Open, we wrote about the problems of finding financial support for projects that evade predictable frameworks, projects like M12 Studio’s. M12 Studio is a group of artists, researchers and writers committed to exploring the aesthetics of rural cultures and rural landscapes on both regional and global scales. Our ever-evolving collective creates projects that vary in form, to reflect the diverse and also-evolving nature of rural environments themselves. Since our projects are context-driven and research-based, experiential and long-term, we cannot always anticipate the outcome of a project—even as most funding sources demand that we must in order to be awarded funding. As such, we spend quite a lot of time applying for grants that seem disconnected from the actual work that we do.

Despite some progress, most of the funding infrastructure for art making in this country is still way behind in terms of its responsivity to experimental practices, and going backwards. Some granting organizations are wising up to the reality of durational art making. The largest inroad has been carved under the banner of “creative-placemaking,” a term that M12 rejects but for a few examples. Given the requirements for accountability and metrics-based evaluation, organizations like M12—both a collective of practitioners and a registered nonprofit—expend a lot of creative energy on applications and reports, presenting the work on panels, etc., where we are usually wrestled into explaining the work through some artificial lens. This is energy and time that could be more productively spent researching, sharing, experimenting, learning, experiencing, meditating, ideating, and risk-taking. The better our art work, the more we’re also contributing as citizens and arts advocates to improving the status of the arts—not just for ourselves as artists, but for others who should know the value of critical and creative activity within our daily lives.

In the spirit of collective improvement, we looked at a few of our own grant reports from the past, and asked ourselves why the numerical reporting process, in particular, is so troubling to us. We decided to focus some remarks there, though more can be said about the time it takes us to identify grants, write letters of interest, meet with funders, write applications, budget, raise matching funds, or submit amendments when things change (which they always do). Here we focus on descriptive reports, usually no more than fifteen pages, and numerical reporting in particular. What follows are select transcriptions from conversations conducted in person, on the phone, and online, between M12 Studio members in recent months. But we’ve been making these observations for many years—every time we produce a grant application. Responding to the “Beyond Survival” call in particular, a couple of us returned to the final reports that we produced mostly for grants supporting “place-based” art projects. We don’t point the finger at particular funders, since similarly metrics-centered questions are found in applications and reporting from federal, state, and local funders, both public and private. Curious readers can visit our website for information about our various project supporters, though these lists won’t include all the grants for which we’ve applied, but weren’t awarded.

In one particular report, the word “experience” is only mentioned once and it’s on the very last page: “‘In-Person’ Arts Experience” and “Virtual Arts Experience.” So, half of the few questions related to experience are devoted to “virtual” experience. We wonder if we’ve forgotten how to be present in real space and time with other people. And, what is an “arts experience” anyway? In his preface to his 1987 book The American West as a Living Space, Wallace Stegner describes his approach to the series of lectures reproduced in the book:

I decided that I would rather risk superficiality and try to leave an impression of the region in all its manifestations, to try a holistic portrait, a look at the gestalt, the whole shebang, than settle for a clear impression of some treelike, spearlike, or ropelike part … I have painted with a broad brush because there was no space to do more; and in the end I have concluded that the space limitation was salutary: it made me concentrate upon the essentials and kept me from getting tangled up in detail. And I have been personal because the West is not only a region but a state of mind, and both the region and the state of mind are my native habitat.

M12 too looks at the gestalt, the physical, and the metaphysical, and the impressions we convey are determined by the experiences we have as artists together with others, and not by the experience we create for others. In accounting for the success of a project, couldn’t the funder simply ask: “Has the project or artwork itself advanced to a deeper place through shared experiences?” Responses to this question will rarely be proven with reference to numbers.

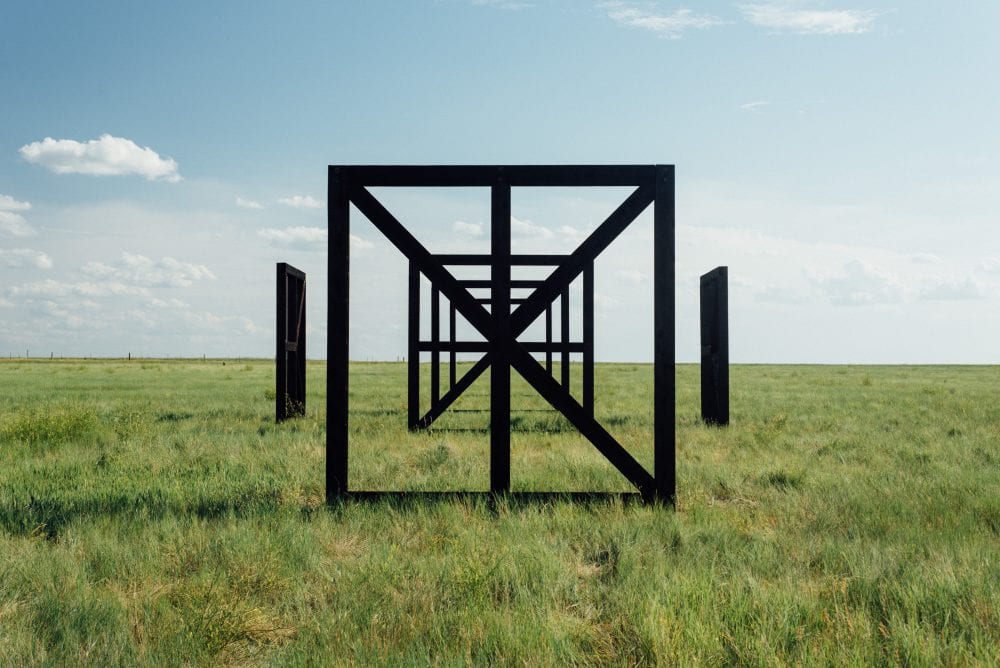

In making the Last Chance Module Array—a site-specific artwork in Last Chance, Colorado—M12 worked directly with Last Chance community members to lease the land where the sculpture sits, survey the site, raise the structures, and complete the finishes. The Last Chance Module Array contains many points of conceptual entry, from farm and ranch architecture to rural planning grids; and is positioned to align with the horizon and celestial phenomena. Participation numbers like four or five might seem insignificant on a report unless one knows that only 23 people live in the town of Last Chance, putting direct community engagement with the piece around twenty percent. The installation is so remote that it’s nearly impossible to gather good numbers anyway. Should we put a clicker near the work? Moreover, the question about a virtual arts experience doesn’t speak to works made within communities wherein the majority of interactions take place in person—poor communities, intergenerational communities, and rural communities frequently lacking a robust internet infrastructure. M12 acknowledges the role of the virtual experience, but considers the term virtual to mean something more broad, to describe the experience of “not being there.” Our Lone Prairie installation at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., the books and records archived in our Center Pivot Library collection—these are place-based but independent of their sites of origin, whether Pierre, South Dakota; Last Chance, Colorado; or elsewhere. Perhaps ask artists instead: Have you considered how people experience or come to know something about your project if they aren’t present for the making? How does your work—as Wallace Stegner describes—give an impression that speaks to the site or experience of origin but in no way tries to document or replace it? How do the virtual, or “non-site” experiences created enable or frustrate the in-person work that happens on the ground?

“Number of Professional Original Works of Art Created – Do not include student works, adaptations, re-creations, or restaging of existing works.”

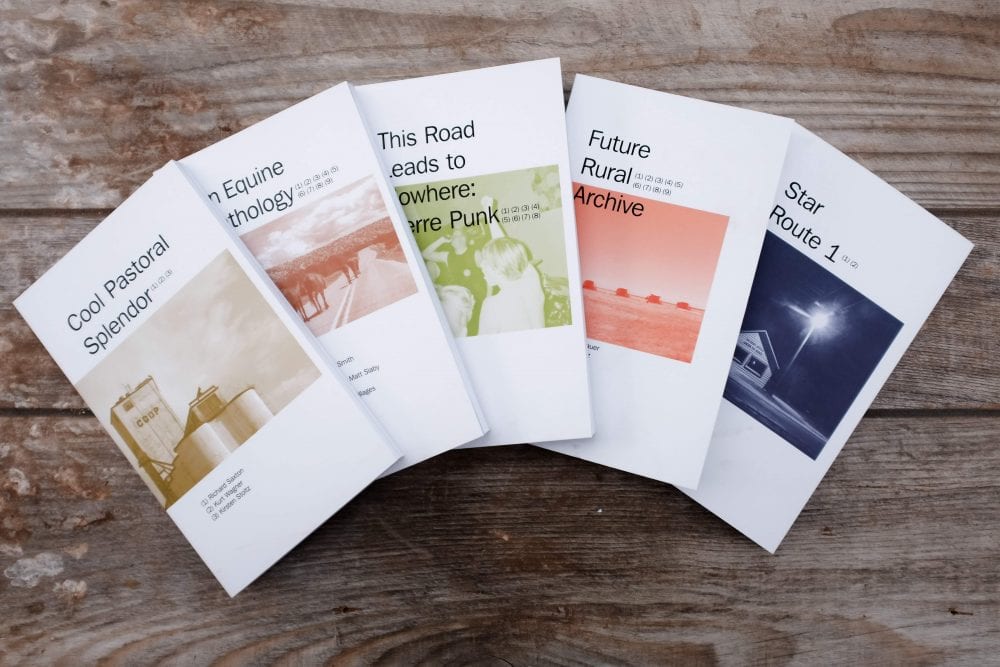

This question assumes a very old notion of art as defined by that which is “original.” No artwork—or idea, for that matter—is original. Adaptation, xeroxing, reprinting: these are critical strategies for making unfamiliar ideas relatable, especially within the rural places where we work. Author Greg Hill wrote a short story, “Now Museum, Now You Don’t,” for M12’s Future Rural Archive book, which was then adapted by Erin Harper as a screenplay for the same volume. Should we have counted Hill’s contribution but not Harper’s? From 2009 to 2013, we partnered with a family racing team in Fort Morgan, Colorado. Together, we created The Black Hornet, a competitive dirt-track race car and durational artwork. The project highlighted M12’s connective aesthetic methodology, which presumes that art making isn’t limited to singular objects or events, insisting instead on allowing the complexity of an artwork, regardless of its form, to resonate in such a way that it becomes a catalyst for cultural discourse. Our project schedule was dictated by the racing schedule at the speedway, not by our organization’s fiscal calendar or any grant cycle. Moreover, there was nothing “original” about the car itself, though it did win several races. Implying that the car in itself is somehow original as an artwork would have diminished the role of the Hall family and their mode of multigenerational cultural expression that was already in place.

These are impossible questions for M12 to answer without compromising our aesthetic worldview, since the research and fieldwork is also part of the work. What’s more, the question implies that quantity is more important than quality. What if a grantee answers only “1” to the question (“Number of Professional Original Works of Art Created”)? Isn’t the fear, then, that the money might not come again because the artist did not do enough with what they were given, even though the essays and the interactions all contributed to the project? Isn’t it more important that at the end of the day a solid project was made or made strides in its making within a grant cycle, regardless of the number of individual photographs or sculptural objects created? Why not just ask the artist to write something about what it is they think they’ve accomplished with their project, in their own words? Such a question allows for the multiplicity of ways in which artists work. And maybe ask them to articulate why they think—or why others told them—what they did is important, which further acknowledges that different things are important to different people.

“Number of Arts Instruction Activities – Include classes, demonstrations, lectures, and other means used to teach knowledge of and/or skills in the arts…”

Joseph Beuys wrote, “Communication occurs in reciprocity: it must never be a one-way flow from the teacher to the taught.”1 Artists don’t “teach” people anything. A learning experience is measured only by the taught, by whomever has learned something. In some cases—in our case almost always—that person is the artist, and not the “public.” Reporting relationships and shared experiences demands qualitative more than quantitative assessments, if some experiences, like familial, psychedelic, or spiritual ones, can even be assessed at all. Haven’t we learned from the Frida Kahlos of the world, from Jimi Hendrix, Agnes Martin, and Leadbelly, that artists need room to roam, room to interpret, react, and transmit, to lead us to new and unanticipated experiences?

In short, this question reinforces a common assumption that is deeply harmful to the arts in general: the assumption that teaching “skills in the arts,” skills that can be achieved through singular events, is something simple. Art making is a profession and though we, as artists, hope that future artists and non-artists alike have some sense for what it is we do, it is not our mission as artists to teach others. Sure, a dentist might show me how to brush my teeth more effectively—because it makes her job easier—but dentists aren’t expected to teach oral hygiene at workshops and public events. It’s more important that we acknowledge the dentist’s expertise, that we appreciate and honor those in the world who’ve chosen such a profession; and, if we’re interested enough, pursue such a profession for ourselves. As it is, such a question furthers the notion that art making is a leisure activity, something that can be learned in the space of a few hours at a workshop. This is not to say that art education isn’t important and that arts-instruction activities shouldn’t take place for children or non-artists; but those initiatives should not be funded by art-making grants, by these grants. Artists aren’t always educators; public artists are more often the ones being educated. In this climate, art makers and art educators are competing for the same funds, and the maker will always lose so long as “education” is perceived to be the more practical or deliverable public good.

The focus on providing a number also implies that more is necessarily better. We’d rather see numerical questions dropped altogether and replaced with open-ended questions that allow us to describe the relational and connective interactions that took place between the artist and others involved. Maybe ask, although it would depend entirely on the relevance to a funder: Do you think your exchange modeled a different way of seeing the world, engaging with others? Or, better: What did you, as an artist, learn from the people, classrooms, etc., you visited in the process of your making—how did your experience shape what you made and the way you will pursue future projects?

“Number of Hours Artists Were in Residence – Count hours of scheduled community/classroom engagement conducted by an artist or group of artists…”

Measuring the quality of an artist’s engagement by their contact hours implies that structured time with artists is necessarily good, and even better if the engagement occurs with others as part of a group. Why not focus on exchange rather than engagement? Ask: How did the community reciprocate? How free did the artist feel to experiment, to push their comfort zone and the comfort zones of others in a way that demonstrates the time it takes to gain mutual respect, understanding, and experience?

“Number of Works of Art Installed in Public Spaces – Include works of art permanently or temporarily installed in a public space.”

Again, this wording is based on a presumption that art outside of a traditional arts context—literally outside—comes better in multiples. Let the artists work with their communities to consider the most appropriate installation “place” for their work; allow for time and space for community members to learn with and, if appropriate, from artists; give artists the respect that a botanist would have when working in public space to add healthy plants to a park or to remove those that don’t belong.

In rural communities, where there is less exposure to both historical and contemporary fields of cooperative art practices, lack of education and experience combined with the explosion of “rural creative placemaking” grants has opened the doors to speculators and folks better suited to bureaucratic desk jobs. Our best visual artists now compete with craft beer makers, savvy startups, and developers—rebranding Main Streets one “arts district” at a time, one “creative economy” at a time. Artists are asked these types of questions: What Community Action Plans were developed? How many Design Plans were produced and how many were approved with support from the community? We can’t imagine how such “plans” could be done properly in a single grant cycle. There’s a proliferation of grand master plans that most small towns can’t afford. What do these do exactly? In our experience, such goals promote the idea that rural communities, as they are, are somehow “less than.” Rural communities shouldn’t look like urban ones because they aren’t. And, while community action plans should be made by cities and counties with the help of state and federal funds, they should not be made with state and federal funds designated for the arts. It’s true that these plans might be helped with input from artists, from more creative thinkers. But, requiring that artists be involved in these conversations in order to receive their funding just sets artists up for failure because they are trained to work in the studio and in the field and not necessarily behind a desk developing “practical” solutions to economic blight.

Enter the number of people that directly engaged with the arts, whether through attendance at arts events or participation in arts learning or other types of activities that involved people directly interacting with artists or the arts…”

These types of questions should include the phrase “if applicable.” The question implies that there must be some “benefit” to an artwork, although what constitutes a benefit is not defined. It suggests art is beneficial when a lot of people engage with it, regardless of the quality or nature of that engagement; engagement, after all, means different things to different people. Attendance is an easily inflatable number and one that doesn’t measure the success of an artwork at all. Kehinde Wiley’s and Amy Sherald’s portraits of the Obamas are remarkable regardless of the number of people who stand in line to seem them. Conversely, thousands will stand in line to take a selfie with the portraits or to experience a Meow Wolf environment, but couldn’t tell you more about the work than about their experience standing in line—they just want the selfie. So, sure: these folks are “directly interacting with artists or the arts.” But focusing on numbers doesn’t measure quality of engagement. Proximity to art is the measure in this question, regardless of its quality—and proximity to artists in particular, regardless of their professionalism or what it is that they actually do. Why not turn the question on the artists? Don’t ask them to speak on behalf of their “viewers,” but rather to describe how the experience of making their project benefited their collaborations or their practice as a whole.

M12 Studio and its work are amorphous experiments in rendering and presenting connective, durational, and experiential processes and projects. We might not have big numbers, but we know the answers to many of the questions that are important to our communities and to our field of practice. So why are we “reporting” to those who know less than we do about what it is that we actually do as contemporary artists within our communities? If the only answer to this question is accountability, then we loudly reject that response as a civically lazy, bureaucratic cop-out. Instead, how about we all be accountable for the depth and strength of the arts? How about we support the risk-takers, the ones opening new pathways of discovery, the ones who roam? How about we decide that arts and culture initiatives of inherent value need no numerical justification? How about we accept that funding not just the arts, but artists in particular, is just as important as maintaining our open spaces and our nature reserves, as funding experiments in outer space, in food and agriculture, in transportation and education—that it is just as important to fund art projects on their own terms, and not according to the terms of other fields, as if art were merely in service to them.

Margo Handwerker is chief curator and director of the Texas State Galleries. She is a member of M12 STUDIO.

Richard Saxton is an artist and University of Colorado professor whose work focuses primarily on rural knowledge and landscape. He founded M12 STUDIO, an interdisciplinary collective that creates and supports new modes of art making in often rural and remote areas.

- Joseph Beuys, “I Am Searching for Field Character (1973),” in Energy Plan for the Western Man: Joseph Beuys in America (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1990), 22. ↩