From Art Journal 80, no. 2 (Summer 2021)

I am a woman of color and an adjunct faculty member at a predominantly white institution (PWI). As I am an artist who makes work about identity politics, my classes are full of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) students who are often negotiating how their identities play a role in their art practices.

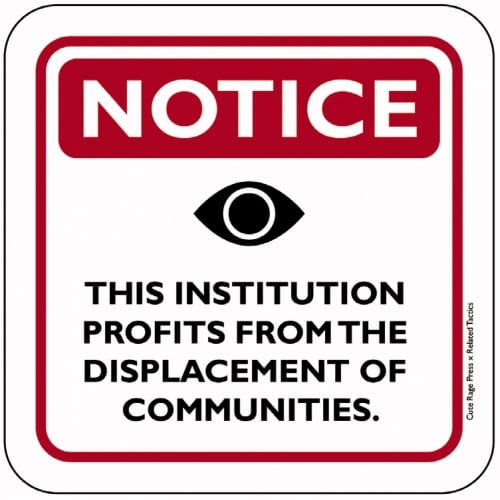

My BIPOC students do a tremendous amount of work to navigate a PWI. They research classes and seek out BIPOC faculty with whom they feel safe to talk about their work and identities. My BIPOC students seek my mentorship and confide in me their frustrations about learning at the PWI. I spend a lot of uncompensated time and energy to listen to, hold space for, and guide students to make sense of and process their everyday incidents of discrimination and racism. Most of their experiences come from everyday interactions in the classroom with their predominantly white professors and peers. As we know, “The maintenance of racial subordination is largely unconscious, expressed through quotidian interactional and environmental microaggressions.”1

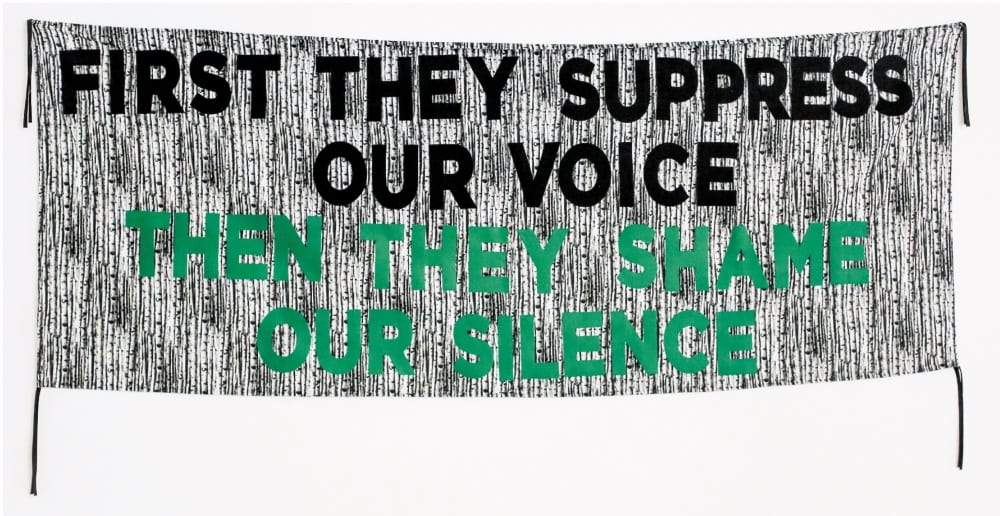

Sometimes the BIPOC students do not do assigned readings simply because they are tired of the white canon. Sometimes they stop showing up to classes because they do not feel safe and included there. Sometimes my most engaged students are seen as “confrontational” in their other courses because they actively question and challenge white supremacy in the classroom as it manifests and is expressed by their predominantly white peers and professors.

Over the years I have written down the concerns that my students have shared with me. These concerns are genuine contemplations and questions from my students that expose an ugly reality of white supremacy in art and art education. Like oppression, some of these points are clear, while others are harder to decode and understand. This is not a comprehensive list, but a constellation of thoughts and realizations. I have written down many points and concerns in my journal, and I have chosen some of the most common concerns here. The list is ongoing and constantly evolving.

Students: “I don’t want to label myself as a _____ [fill in the blank with labels such as Black, Brown, Indigenous, immigrant, trans, queer, disabled] artist because I don’t want to be pigeonholed or boxed in.”

Students: “How come all my work gets read as it being about me being _____? Shouldn’t I be the one to say if it’s about my identity or not?”

Students: “I don’t like _____ [fill in the blank with the name of an artist of students’ identity group]. They are a sellout and token. They just make work that white people like.”

Students: “It’s like _____ [fill in name of famous blue-chip artist of students’ identity group] is the only _____ artist people know.”

One of the most common fears that my marginalized students have is to be labeled as just a _____ artist. This often comes from firsthand experience when white professors and peers have labeled them and their works (whether or not about race or identity) without consent and without realizing that they are violently enacting dominant culture by labeling those who are not of dominant culture as only that. Students have a fear of being “boxed in,” “pigeonholed,” and “reduced to a label.” When I ask my students why they feel this way, they often respond that they do not want their works to be an easy read or that their identity as _____ is all that their work is about, and it will always be framed that way. And when students feel empowered and call themselves _____ artists, they are told not to “limit” themselves. The students witness that white, cis, heteronormative artists are never labeled as white, cis, and heteronormative. Marginalized people carry the weight of representation—a task that puts us in situations of increased critique and criticism.

Making art about one’s identity opens us up for the dominant culture to label our work as mere representations of our communities and peoples. Therefore, the engagement by viewers often becomes superficial and sometimes uncomfortable. The artists and our artworks are reduced to that “which is intelligible within white racial logic.”2 We either simplify our own work due to pressures of this internalized white racial logic, or our work gets simplified and defined for us by white racial logic. Either way, we are left in a situation where whiteness defines us.

Also, these labels are implanted notions of marginality. The irony is that the labels depend on the whims of the art world and art philanthropy. Art about politics and identity is sometimes in fashion and sometimes out of fashion. The financial conditions of artists and the opportunities available to them are impacted by these whims. We are subject to the capriciousness of art world trends, and these are the forces that students, too, are struggling with. How do we survive and thrive in an art economy that values its power to marginalize us?

For our own communities and people, we open ourselves up to the impossible task of being able to represent who we are as complex peoples. From within our communities—when the white racial logic has been reflected back to us—our work is seen as flat, and we are labeled “tokens” or “sellouts” when the spotlight on our works as representations of our communities is seen as creating depictions of ourselves that are digestible for the dominant culture. Students also express a sheer frustration that they only hear the same artist recommended to them in every critique. The real issues are the dominance of white racial logic and that there are not enough representations of marginalized communities in which marginalized artists create nuanced narratives that complement and complicate other narratives representing the same communities and identities.

As an educator, I ask my students, What is the alternative? What are other ways we can talk about our identities and how they inform our practices? Do we not label ourselves? And if we do not, is that enacting the same attitudes of white, cis, heteronormative artists who evade labels? If others are going to label us and our works anyway, is it better to take control of how we are labeled? What are movements and art movements we can use or invent for ourselves to push back against white racial logic?

Students: “Can I make work about being _____?”

Me: “Yes.”

Students: “But I’m so privileged.”

Me: “We are all privileged in one way or another. We have to use our privilege to speak louder.”

I have students who fear making work about their own identities as marginalized people because they hear critiques by people of dominant culture that can be decoded to express, Who are you to represent your own people or culture? Who are you to speak for them?

A former student who is undocumented asked me, “Can I make artwork about being undocumented when I am so unique in my privilege to have this access to higher education?” (My response: “Yes, because you’re undocumented.”) This questioning of self makes me really angry and sad because it reveals that the students are internalizing dominant depictions of themselves and their identities. The undocumented student feels privileged and unique because dominant culture sees being undocumented as not having access to higher education, particularly at some of the most expensive private art schools in the country. I have Black students who question if they can make work about police violence when they have not been beaten or experienced firsthand police violence themselves, even though they could be a victim at any time.

For me, I read this as a classic, racist “but you aren’t like those other _____ people” sentiment. BIPOC art students and artists are constantly having to justify our own identities and place, particularly when we at the same time have access to higher education and other predominantly white spaces. These sorts of critiques do not only come from dominant culture—we often find them coming from our own communities.

Students: “Am I appropriating my own culture?”

Me: “No.”

Students: “Am I fetishizing my own culture?”

Me: “No.”

These sorts of statements are often made by students of the diaspora, Indigenous students who do not have access to their cultures due to genocide, and Black students who are descendants of enslaved people looking toward their ancestors. When these students engage in their own cultures at these PWIs, the validity of their access to their own culture gets questioned and often deemed inauthentic. At its worst, these sentiments get internalized, and students then do not feel that they are authentic enough. As in the former example, when we do make work about our own identities and cultures, as complex as they may be, our positions are often challenged and policed by white racial logic.

A former student who is Palestinian and grew up in Dubai asked, “Can I make work about being Palestinian when I’ve never even been to Palestine?” (My response: “Yes, because you’re Palestinian.”) This again shows me an internalization of what it means to be Palestinian based on white racial logic. It sees only those who live in Palestine as being able to depict what it means to be Palestinian, when the majority of this population lives as refugees outside Palestine.

Access to our own cultures and histories is hard to find in PWIs and more broadly in our Western societies. However, when I find students teaching themselves through the resources available to them, they may encounter questions such as: What are your sources? Where are you doing your research? Where did you find that traditional material? Where are you learning these traditional techniques? Why don’t you go to _____ [fill in name of country] to really learn about _____ [fill in topic or technique]? Well, is this even the way it is done in _____ [fill in name of country]? Isn’t what you’re doing cultural appropriation? For example, when I have applied for full-time faculty positions, hiring committees refuse to accept that I am skilled at Korean traditional embroidery techniques because I have learned from Korean immigrant ajummas (aunties) in the United States.

When they express enthusiasm for their own cultures in their work, my BIPOC students are told they are fetishizing their cultures. Questions of self-appropriation and self-fetishizing come predominantly from white professors and peers critiquing the ethics of the work as if the artists were white themselves and questioning if they truly have access to that culture. I feel that dominant culture is excellent at co-opting critiques of itself and placing them onto those who are marginalized, without any self-awareness. These questions are another reminder of the limbo of diaspora and displacement BIPOC artists experience, where we are made to consider ourselves not authentic enough to incorporate our own cultures, traditions, and histories into how we represent ourselves.

The previous set of student comments reveals how representation is policed by whiteness. The sentiments expressed by my BIPOC students reveal the white supremacy at work to say that it is not your place to define yourselves. Representation of self by BIPOC artists is heavily questioned and critiqued by a white logic that operates from a clear ignorance of understanding complex identities and that holds onto flat and racist definitions of peoples. It still denies us the ability to define ourselves, and even to align ourselves with our own people. When we represent ourselves and it does not fit with the representation of us by white logic, we are told that we are not that and that whiteness still has the power to represent and define who we are.

Students: “My professors are always telling me to read about my own life and experiences. Why aren’t my experiences enough?”

In academia and in the art world at large, “research” is prioritized over people’s lived experiences. My BIPOC students who make work about being BIPOC from personal lived experiences often tell me that they face a lot of pushback in their critiques. Their peers and professors say that their “narrative” work (often said as a derogatory term) is “too personal.” They are told that their work is “art therapy and not art” and that they do not have any “objective distance from their subject matter.” They are told to engage in “theory” or “research” to validate their lived experiences or to contextualize them in a larger frame. Often the texts students are asked to read are anthropological examinations that are racist and highly problematic. Students often vent to me that their professors whitesplain racism or their own histories to them because these professors have read about these topics, and thus that “learned experience” gives them permission and authority.3 Of course, we know that sometimes this happens because professors want, at best, to relate—and, at worst, to flex and show that they are “woke.”

The pressure is always on the BIPOC student, then, to read and research in order to talk about their work and their own lives. And, of course, the “research” demanded of them is most often not part of their curriculum, so they are asked to do more work to learn how to talk about their own lives. They are asked to be the researcher and the researched.4 This prioritization of learned experience is yet another door to make art inaccessible and difficult for people who do not learn to talk about their art and frame it within “research” and “theory.”

I participate in this dynamic in which learned experiences are prioritized. With an undergraduate degree in ethnic studies, I am an avid reader of critical race theory and on the topics important to my work, such as immigration policy. My work starts from my own lived experiences, and I read and research, sometimes to give me confidence and guidance—but sometimes I use this “research” as a defense mechanism to be able to slap back to critiques with a slew of citations. Unfortunately, the pressure is on BIPOC to be well read and able to give “informed” views opposing dominant culture. I too encourage my BIPOC students to read and research more, and sometimes it comes from a place of using research to be able to translate and code-switch into art jargon and to use it as self-defense. I point them to texts, mostly by women of color feminists, that challenge the ways we understand and places we take in knowledge, and that show it is within our lived experiences that the formation of knowledge takes place.

BIPOC students are in a burdensome place where they are faced with tremendous scrutiny whether they do or do not frame their art practice around how they are marginalized. I witness them enduring an ongoing process of emotional pain and exhaustion from constantly being asked to lay themselves bare and from confronting a constant questioning of themselves, their experiences, and their identities. I watch them negotiate these challenges in every presentation and critique of their work, when they have to assess how much they open themselves up to white racial logic based on each situation they are in. They ask themselves and me, How much do I have to explain myself? Do I feel safe being vulnerable to share my experiences and concerns? What negative and discriminatory feedback can I anticipate? How do I respond and get ahead of it? Do I trust the people in the room to give me feedback? Who can I really talk with to get the types of feedback that I’m looking for? And at its worst, What am I even getting out of this place? Do I even belong here?

As institutions are attempting to do more work in terms of diversity and the inclusion of BIPOC faculty and students, many of these conversations happen with broad language and initiatives that often do not examine daily interactions within the classroom. As educators, we need to consider how we are playing a role in enforcing white supremacy.

I am guilty of having committed some of these microaggressions, of making ignorant and discriminatory statements, whether overt or subtle, without an awareness of how toxic these statements and sentiments can be. I am constantly learning about and unlearning my own manifestations of white supremacy and racism.

As a BIPOC artist, in my art practice I can express my anger and vitriol toward white supremacy through callouts and humor. My pedagogical approach is different, as I approach all my students with tenderness and care. I trust that they already hold a lot of power and knowledge, and at the same time are still learning about who they are, their politics, and how to talk back to power. I am an educator because the classroom is a one of the places where I feel the most empowered, where I can nurture my students to flourish into artists who dream to create radical futures.

As adrienne maree brown said in a recent virtual lecture I attended, “We can be scholars of belonging,” denoting that we can create an irresistible place for each of us that makes space for our “harmful, victim, and hurt selves.”5 The classroom space can be a space where we learn and unlearn together. I try my best to create a safe environment in the classroom where we can be accountable and question each other in what we say and do. I work to create a trusting space where we can all make mistakes and learn from them together. And my students are tremendously generous. Sometimes their callouts are sharp and clear, while at other times they are muddy and clumsy. I ask students to push back against a culture of politeness that often vilifies marginalized people for speaking out and asking for accountability, while treating everyone with respect. We need to build a practice where we can gently call each other out and receive it as an act of love and generosity, where we are learning from and with each other.

We collectively and clumsily fumble in our language and actions to talk through and to confront our own manifestations of racial subordination at work. I find that the students are deeply committed to working together to unlearn and work against white supremacy, patriarchy, and other manifestations of oppression. We can strive for the classroom to be a liberatory space where no matter who you are and your positions, we can all talk, listen to one another, trust each other as “victims of a system that doesn’t love anyone,” and accept that the process is messy.6

Aram Han Sifuentes is an artist/scholar who creates socially engaged projects that seek to reimagine inclusive and humanized systems of civic engagement and belonging. She earned her BA in art and Latin American studies from the University of California, Berkeley, and her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she is currently an associate professor, adjunct.

- Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández, Amelia M. Kraehe, and B. Stephen Carpenter II, “The Arts as White Property: An Introduction to Race, Racism, and the Arts in Education,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Race and the Arts in Education (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 6 (emphasis in original). ↩

- Ibid., 7. ↩

- Lived versus learned experience was first framed for me by George Aye from Greater Good Studio in a workshop: George Aye, “Power and Privilege Workshop,” Equity Museum Practice Committee at the Art Institute of Chicago, January 23, 2020. ↩

- See Angela Davis, in “50 Years of Imagining Radical Feminist Futures: A Conversation with Angela Davis and adrienne maree brown,” Women’s Resources and Research Center at University of California, Davis, November 17, 2020. For an audio recording, a transcript, and other resources relating to the event, see https://www.davisvanguard.org/2020/11/uc-davis-womens-resources-and-research-center-hosts-angela-davis-and-adrienne-maree-brown-in-50-years-of-imagining-radical-feminist-futures/. ↩

- adrienne maree brown, in ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩