Conversations is a series of critical dialogues between artists, designers, historians, critics, and curators on timely issues in the field. Read this interview in Spanish here.

The international “sex appeal” of the Cuban artist living on the island has largely depended on the perceived “mythological” connection with the revolutionary process of 1959. Whether studied through key concepts such as revolution, utopia, or socialism, the idea of the “revolutionary artist” permeates the conception of a logical corpus of art practices associated with the social movements that characterized the 1960s in the Caribbean and Latin America.

The case of Sandra Ceballos is significant because it does not align with any of the preconceptions that have traditionally supported the history of post-1959 Cuban art, both on and off the island. Although her name is barely mentioned during the political and cultural revolts led by the artists of the 1980s generation, she was present at and participated in a multitude of performances during the period. In 1994, with the artist Ezequiel Suarez, Ceballos founded the gallery Espacio Aglutinador1 which is the longest-running independent art space in Havana. Since then, Ceballos’s small house in the Vedado neighborhood of Havana became a space of artistic and social experimentation within the arts in Cuba. Considering that the state controls most cultural institutions on the island, the political risk of keeping this space alive is part of her everyday challenges.

Ceballos’s work as an independent curator is integral to my research because it represents a visible development of Cuban culture on the island that engages in a transnational field of mutual interconnections. The idea of a narrow nationalistic experience of Cubanía (Cubanness) has no place in Ceballos’s artistic practice.

This conversation took place over WhatsApp in July 2024. It reflects on the passions and perils of being an independent artist and curator residing in Cuba, and the possibility of persevering, as Maria Lugones reminds us, under the stress of multiple oppressions.

Maria de Lourdes Marino: You graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts, San Alejandro, in Havana, in 1983. How has your artistic practice shifted throughout the years?

Sandra Ceballos: My career as an artist began in 1985 with an installation proposal based on the artistic trends of the moment—Italian Transvanguardia and the New Wave, among others—which were very influential during the eighties in Cuba. Also. I worked on abstract painting following the same influences. At the time, I was interested in international fashion, too.

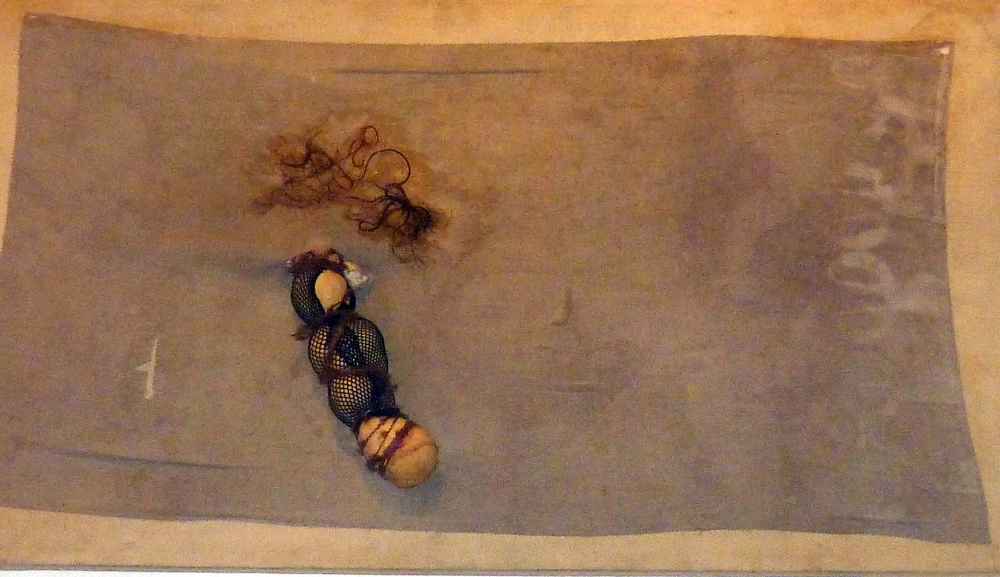

I worked on my pieces spontaneously, without a prior sketch, ambitious research, or philosophical studies. I was not interested in scrupulous or orthodox theories, neither complex readings on aesthetics, nor historical, social, or civic projects. This practice has changed over the years. Today I work with statistics and research on political censorship, rape, suicide, and domestic violence. On the other hand, for the project Expresión Psicógena (1995–2024) I had to study psychoanalysis and the diagnoses of psychosomatic disorders.

MLM: When and under what circumstances does your work as a curator begin?

SC: My interest in curating began at the end of the 1980s when I saw so much discrimination and corruption within the world of the arts: Artists with the stomach to negotiate came out thanks to “extra-artistic” efforts, while others—because they were timid or for not allowing themselves to be bought by politicians or for being homosexual or religious—were swept away and banned by the official Cuban machinery.

At the end of the ’80s, several artists were put in prison for creating critical work and others had to go into exile to be able to work without censorship or political pressure. So, in 1994, parallel to the Havana Biennial, Ezequiel Suárez and I decided to organize a two-person exhibition in my studio in Vedado called Arte Degenerado en la Era del Mercado (Degenerated Art in the Market Era). There I exhibited my then-new series Absolut Utopia, with appropriations of artworks by Russian artists who were expelled and exiled from the former Soviet Union. Ezequiel exhibited paintings on cardboard that mocked political slogans.

MLM: What were your goals for Espacio Aglutinador when it was founded?

SC: Our goal was to do justice to discriminated artists, men, and women, censored, and forgotten, some were older in age and others very young. We were also interested in exhibiting Cuban artists in exile, foreigners, and official artists. This was a way to practice democracy in the arts in our country. We wanted to show that the quality of the artworks and artists cannot be measured by age, nationality, political or religious affiliations, gender, or curriculum, much less academic titles.

MLM: Have your aspirations changed regarding Aglutinador?

SC: Aglutinador fulfilled its function. It liberated the orthodox mindset of many art critics, curators, and artists. It also opened a path toward independent art in Cuba and the practice of integrity consistent with the right to freedom of expression. The aspirations will always be the same: to try to free minds and do justice in art.

MLM: How have you been able to manage your work as an artist and your work as a curator at Aglutinador?

SC: I don’t even know, but it has in no way been programmed by any type of discipline or calculations. I wanted to enjoy both working choices as a curator and artist. I have also had to constantly build an armor of great courage to survive in the face of verbal sabotage from bureaucrats, artists, and curators who serve the Cuban government. I have also received many threats from the Cuban political police over the years.

MLM: The curatorial work at Aglutinador is frequently a collaborative effort with other artists or curators. How has this dynamic influenced the development of this space?

SC: In the more than one hundred events in Aglutinador’s history, there have not been many collaborations with other curators. In the first three years, Orlando Hernández and Gerardo Mosquera collaborated on some exhibitions as co-curators with Ezequiel and me. Since 1999, I have been the only curator. However, on some occasions, I have had the support of artist René Quintana, specifically in museography and production. The artists Bárbaro Martínez, Andy Rivero, and Natalia Triana have helped with photographic and video documentation. Since 2005, I have invited only six curators, including Cubans and foreigners, to work on very specific events: Eugenio Valdés, Magaly Espinosa, Coco Fusco, Rachel Weiss, Elvia Rosa Castro, and Giselle Victoria.

MLM: Were there any other independent art spaces in Cuba in the ’90s? Have you ever co-curated events with other independent spaces?

SC: Starting in 1995, some private venues and galleries with a certain following were created, such as Telégrafo, Ermy Taño’s studio, and Cristina Vives’s house. Later, the open studios began, such as the Sandra Ramos studio house, especially during the Havana Biennials, starting in 2000.

I did not collaborate with independent art spaces in Cuba, but I was invited by the Drawing Center of New York, in 2000, to co-curate, with Luís Camnitzer, an exhibition of drawings by the Cuban artist Santiago (Chago) Armada. I was also invited to participate—as Espacio Aglutinador—at the International Fair of Alternative Spaces (FAIR) at the Royal College of Art in 2002. And finally, a co-curatorship with the artist Glexis Novoa for the Marcos Castillo Gallery stand at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2024.

MLM: I think many people wonder how you have managed to maintain Aglutinador for so long. How is it that censorship or the precariousness of life in Cuba hasn’t driven you into exile?

SC: It has to do with my personality. I am persistent, I don’t let myself be bought, and very industrious.

In my opinion, practicing creative freedom in Cuba means withdrawing into privacy and remaining firm in civic and moral principles or going into exile. It’s my way of being and thinking. Warring was a pleasure. However, I am already on my way to another country.

MLM: Where are you going and for how long?

SC: I have an exhibition at the end of the year in Spain and let’s see what happens after that. This exhibition is about feminicide in Cuba. It is part of the results of a fellowship granted by PEN International and Artists at Risk Connection (ARC) as part of the Cuban Migrant Artists Resilience Fellowship. The exhibition, titled Desamparo con alevosía, is a tribute to all the victims of feminicide: women and girls who were raped, tortured, and killed. They received no support from local agencies or the police, even from those that had denounced the mistreatment.

MLM: Of all your curatorial projects, which ones do you think have impacted or influenced Cuban society the most?

SC: Cuban society doesn’t give a damn about the visual arts. I think one of the exhibitions that had the most impact was We are porno, sí (We are porno, yes),2 perhaps because of the topic. The one with the most international media coverage was Curadores, Go Home.3 The latter resulted in vocal criticisms from the National Council of Plastic Arts and its director/defamer, Rubén del Valle.

We are porno, Sí (We are porn, Yes), 2007 (photograph provided by Sandra Ceballos)

Curadores, go home (Curators, go home), 2008 (photograph provided by Sandra Ceballos)

MLM: What is the current state of Aglutinador and yourself as an artist?

SC: Given the terrible conditions that people in Cuba are currently experiencing, given the extremely repressive situation and the constant, major violations of human rights, it is now even more difficult for me to continue living and creating in an enslaved, dejected, and violent country.

I have started a new series of paintings and installations concerning gender violence and crime in Cuba. I am also working on another series with texts and drawings by Cuban writers and poets who have contemplated suicide. Both series are still in development, they are works in progress.

Sandra Ceballos was born in 1961 in the province of Guantánamo, Cuba, and graduated from the San Alejandro School of Fine Arts in 1985. Ceballos’s artwork has been shown in El Museo del Barrio, New York, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, and Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City, among many other galleries and museums.

María de Lourdes Mariño is an independent researcher and curator, currently a PhD candidate at Temple University, where she specializes in modern and contemporary art from Latin America and the Caribbean, including its diaspora. Mariño’s research interest centers on the history of Cuban and Latinx art from 1980 to the present.

- Over the years, dozens of Cuban artists residing on the island, as well as artists in exile, have presented work here. Young Cuban artists who want to test out challenging projects as well as older Cuban artists who have encountered censorship and institutional indifference have sought out the gallery to create memorable exhibits. Notable artists from other countries have also exhibited at Aglutinador, including Santiago Sierra, William Cordova and Leslie Hewitt. ↩

- The fact that pornography is illegal in Cuba only makes it more desirable. For this group exhibition, Sandra invited artists to create humorously erotic works in a variety of media. ↩

- For this project, Sandra invited artists to install whatever they wanted wherever they wanted in the gallery, a gesture meant as a rebuke to institutional and curatorial control of Cuban art. The exhibition featured a collective mural-performance in which arts professionals were invited to write the names of censored exhibits as well as the names of those who had censored them. ↩