The Feminist Interview Project, organized by Keren Moscovitch and Elizabeth S. Hawley of CAA’s Committee for Women in the Arts, examines the practices of feminism by interviewing a range of scholars and artists. The project aims to preserve the living histories of feminist art practices, while interrogating and expanding the boundaries of what might be considered feminist. Throughout its interviews, this project reimagines the possibilities of feminist practice and feminist futures by exploring a diversity of perspectives and approaches to research. This collection of interviews aspires to critically examine the relationships between feminism, feminist art, and the lived realities of women, nonbinary and female-identified artists and scholars across the globe.

With a career spanning nearly half a century, Mónica Mayer (b. 1954, Mexico City) is seen today as the most prominent feminist artist in Mexico and foundational in the development of Mexico’s feminist art movement, beginning in the mid-1970s. Based in Mexico City since 1982, art historian, curator and writer Karen Cordero Reiman (b. 1957, New York) has been fundamental in shaping and reflecting critical and public understanding of feminist art in Mexico. Against a backdrop of ongoing and increasing gender-based violence, in a country that has ranked at or near the top in femicides in Latin America since such numbers were recorded, together, over decades, the artist and the art historian have planted the seeds of a blossoming of feminist art in Mexico, while nurturing an enduring friendship marked by collaboration, exchange, and support. The pair began to collaborate in the mid-1980s, and have since produced groundbreaking multimodal events combining feminist pedagogy, curation, art making, and activation of archives, including the 2016 exhibition Si tiene dudas . . . pregunte: Una exposición retrocolectiva de Mónica Mayer (When in Doubt . . . Ask: A Retrocollective Exhibit of Mónica Mayer), Mayer’s first retrospective exhibition, at the University Museum of Contemporary Art (MUAC) in Mexico City, recognized by Hyperallergic as one of the top fifteen exhibitions in the art world that year.1

Bárbara Tyner, a scholar of Mexican feminist art, and Gabriela Aceves Sepúlveda, a feminist artist and feminist media historian, members of the Committee for Women in the Arts, invited both to reflect on their collaborations and their roles in shaping Mexican feminist art, artivism, curation, and pedagogy in the last four decades in Mexico and beyond.

In keeping with the established interview format of the CWA Feminist Interview Project, we began our conversation with a broad question:

Gabriela Aceves Sepúlveda (GA): Mónica and Karen, what is feminism to you?

Mónica Mayer (MM): For me, feminism is a way to understand women’s oppression under patriarchy and how this affects us personally and socially, and this understanding allows me to be aware of other forms of oppression. The goal would be to get rid of oppression as a dominant structure.

Karen Cordero Reiman (KCR): Well, I agree with Mónica and would add that, for me, feminism is using the critical lens of gender analysis to shed light on the unequal, oppressive, and hierarchical power relations in our history and our world. And seeking more horizontal and dialogical ways to transform that relation.

Bárbara Tyner (BT): Mónica, your feminist art practice started in the mid-1970s in Mexico City as an art student active in the Mexican feminist movement, combined with your study at the Feminist Studio Workshop at the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles, 1978–80. Karen, you arrived in Mexico in 1982 as a budding art historian with a solid social consciousness already in place. You met Mónica when you took her feminist art course (the first of its kind in Mexico) at the Academy of San Carlos. And the rest is history. Our second question is about Tlacuilas y Retrateras (1983–84), one of the first feminist art collectives in Mexico, that emerged through Mónica’s landmark course.2 The group’s best-known project was the 1984 multimedia event La Fiesta de Quince Años, a multimodal inquiry into the traditional Mexican coming-of-age party for young women. The event featured an exhibition of more than thirty artists, poetry readings, and artists and attendees participating in various performances. This was one of the first forays into public feminist performance and social practice art in Mexico in the 1980s and can be seen as both a marker for Mexican feminist art history and a point of emergence for your collaboration. What do you see as its effects culturally, socially, and for you, as people, artists, and art historians?

KCR: Well, I can tell you my point of view as a young art historian who recently arrived in Mexico and became involved in this course, which then evolved into a feminist art group.

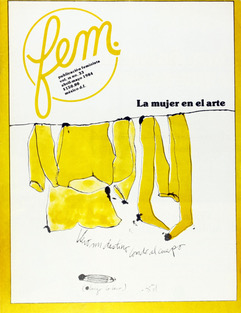

The course was one of the first exercises in feminist art pedagogy in Mexico. La Fiesta de Quince Años is the most well-known aspect of the course, but many other things happened that, in retrospect, were also very important, culturally and socially, and for me as an art historian. One of them was getting to know the feminist art milieu in Mexico City and getting to know several key feminist artists. We researched women artists in Mexico, which led to the article we published in Fem.3

The course was my first immersion in the developing feminist art world in Mexico. It also related to my previous experiences of working with small groups in the US. Monica’s course reinforced the dynamic of working in a small group and in a horizontal way, where individual identities and individual creation weren’t the focus, but rather collective creation.

As a group, we started to think about what we wanted to do as a final project, and after discussing various possibilities, we came up with the fiesta de quince años as a topic. It was an eye-opening experience for me because I had never heard of this traditional Mexican celebration. Its exploration allowed me to learn about more about stereotypes of female identity in Mexican culture, while simultaneously participating in their critical framing through the process of feminist creation. For the event, I made a black dress decorated with items related to the quince años celebration that I purchased in shops in Tepito and in the Merced (traditional market neighborhoods), such as buttons in the form of parasols and high-heeled slippers that I sewed onto the dress. I was assigned the role of curator of the exhibit that formed a part of the event and made a pink satin wreath for the entrance to the show that evoked Judy Chicago’s vaginal iconography. I also contributed a collage piece called La Ley del Hombre (The Law of Men), titled after a fotonovela (an illustrated crime/romance novel) from which I incorporated images, together with more trinkets from the Merced, outlined in red lipstick and complemented by epithets commonly applied to women printed with letterset blocks.

The event used all different types of creative means to analyze and deconstruct the celebration of the quinceañera. We were respectful of that tradition but at the same time we reflected on what happens when you’re growing up and are learning to, or being encouraged to, adapt to conventional female roles and all the different forms of repression that are part of them.

The public reception of the event was varied. In terms of attendance, both from the surrounding neighborhood and the art community, it was much more successful than we had imagined. Within the art community, the event surprised people and made them uncomfortable in some senses. Commentaries—both positive and negative—were published in the newspapers. So much attention was a little overwhelming for us as a group, and afterward, it was hard for us to figure out how to continue and move forward. Even though the group didn’t continue as an active feminist art group, many of us kept in contact.

In terms of Mónica’s and my collaborations, it was the starting point. Around the same time, both of us also started teaching courses at the Universidad Iberoamericana, where I would later work for many years.

MM: It’s hard to tell what the effects of La Fiesta de Quince Años celebration were, but it was an early example both of feminist art and social practice in Mexico. There were also several other interesting aspects: it was intergenerational, interdisciplinary and non-hierarchal. We had women participating between the ages of twenty and twenty-four, we had artists and art historians, and things were decided collectively. Sometimes this was confusing for me because I was facilitating the process and participated in every aspect, but I was not part of Talcuilas y Retrateras.

One effect of the workshop and the event is that they were shocking to many people. To begin with, people at the school were upset that it was an all-woman’s group, even though this had happened because no men enrolled. This was so shocking at the time that, several times throughout the workshop I was facilitating, the workers at the school locked us out of the classroom, which is why we often ended up at the Café Moneda, a couple of blocks away. However, both women and men participated in La Fiesta de Quince Años, which was quite unusual for a feminist art event.

The structure of La Fiesta de Quince Años itself was also different. The project was based on research and our personal experiences, which was unusual at that time. We studied about the origins of the quince años celebration in Pre-Hispanic and Colonial times, its sociological and financial implications, and we all shared our own experiences.

We also fundraised for the event, which was unusual before the nineties. For example, we got Sanborn’s (an upscale department store chain) to donate the cake. We also collaborated with people outside the artworld, such as feminists and people in the media and theater. For example, a young musician composed and performed the music for the ball. We also invited artists and critics as madrinas (godmothers) and padrinos (godfathers) of the event, keeping the structure of quince años celebrations. This allowed us to involve critics and older artists. And there was a lot of humor in the whole project. We were questioning the fiesta de quince años, but respectfully, with a sense of humor. Only women artists were invited to participate in the exhibition, except for Nahum B. Zenil who accepted being our token male artist (so they couldn’t accuse us of not inviting men). The exhibition showed a great variety of works that were very critical of class, race and gender issues, but we presented them with a smile in our faces.

We expected about two hundred people at La Fiesta de Quince Años, and about two thousand arrived. Total chaos. A couple of younger participants in the group had a rough time. They presented a very intimate performance in the middle of the patio, but it was so crowded, nobody could hear them. Raquel Tibol, the most famous art critic at the time and one of the madrinas of the event, started yelling at them, demanding they stop. They were shocked and scared.

The project was also an interesting teaching/learning experience. The group had to learn how to do things like fundraising, press release writing and working collaboratively. None of this was taught at art school. We also worked on defining our audiences, which included the people living near the school, a lower income community that was never taken into account as an art audience, but we also invited art critics, artists, feminists, the media, friends and family.

And as Karen mentioned, it was very complicated with the press, who were all present, but basically made fun of us because our “sketches” were not (considered) good. They had never even heard of performance. However, we are clear La Fiesta de Quince Años was a foundational event in contemporary Mexican art.

The group disbanded after the workshop ended as a result of internal problems at the art school leading to the suspension of all extracurricular activities.

KCR: There was also experimentation with new technology. I remember Maria Guerra’s performance used a “video beam,” as digital projectors were called at the time. Also, there was a porous, dialogical relationship between Tlacuilas and the other two feminist art groups at the time—Polvo de Gallina Negra and Bio-Arte—and also with artists not listed as part of Tlacuilas y Retrateras, but whom I remember meeting in the context of the course, like Yolanda Andrade. The event reflected the collaboration between what you might call a very small collective front of feminist art in Mexico City. I think the course had a role in making that possible. There was also a fluid interrelationship between the feminist art scene and the political scene of feminist activism; one of the first activities of Tlacuilas as a collective was our participation in a demonstration protesting violence against women, in October 1983.

Another thing that comes to mind is how I have employed the methodology of working together as a group and having to do everything involved in producing this event—in the other exhibitions I organized much later with my students in the university. Taking charge of all aspects is important in terms of feminist art. This project introduced that model in Mexico, maybe not in a very conscious way. But it was something Mónica brought from her work in the Feminist Studio Workshop and that I, and probably other people involved in the project, assimilated through that process, and have reproduced in our own pedagogical experiences.

In terms of the impact of Tlacuilas y Retrateras, the group acquired a mythical status because it didn’t continue and hasn’t been sufficiently historicized. It was sort of like a bomb that went off and dissipated. Even though there are a few articles, some photos, and, of course, people’s memories and archival material, there is no clear registry and analysis of the group’s activities.

Tlacuilas put the topic of the fiesta de quince años—and other events that produce and reproduce female stereotypes—on the radar of emerging feminist artists. In retrospect, La Fiesta de Quince Años has had a great deal of resonance with other generations of women artists in this respect. Its impact and meanings are still unfolding in contemporary times.

GA: The repercussions of this rich episode in Mexican feminist art—its impacts, meanings and effects have certainly informed subsequent collaborations, including your important work with Ana Victoria Jiménez beginning in 2009.

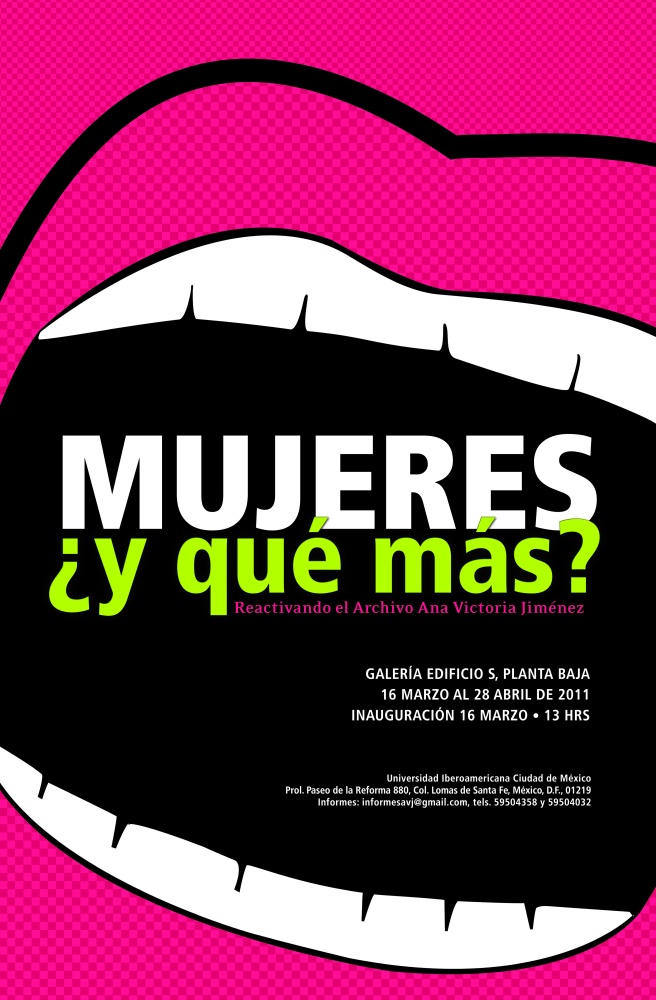

You both began working with the archive of Ana Victoria Jiménez, a unique collection of photographs, prints and ephemera documenting feminist activism and art in Mexico City from the 1970s to the 1990s. To bring attention to its historical importance in the context of ongoing violence in Mexico and renewed feminist activism, you organized various intergenerational workshops with students, scholars and artists to reactivate the archive, which produced two very positive outcomes: the exhibition Mujeres ¿y que más? Reactivando el Archivo de Ana Victoria Jiménez (Women, and what else? Reactivating Ana Victoria Jiménez’s archive) in 2011, and securing placement for the archive in the Special Collections of the Biblioteca Francisco Xavier Clavigero at the Universidad Iberoamericana (the Iberoamerican university, or the “Ibero”). Now accessible to the public, it is the library’s most consulted collection.

You both knew Ana Victoria early on, Mónica, as a co-militant in various feminist collectives in the 1970s, and Karen, in 1984 in Mónica’s feminist art course. When did you both begin to understand the historical value of her archive? Can you tell us how this project came about?

MM: I think we have always understood the importance of Ana Victoria’s archive which documents the early feminist movement in Mexico City. It’s also one of the few archives with information on feminist art. Ana Victoria was trying to place it at an institution, and offered it to two public universities with women’s studies programs. Both of them rejected it, claiming lack of space or interest. Ana Victoria was upset that nobody wanted her lifelong work. So, we started talking about it and formed a group to push for a university to accept it. We organized events in different venues in Mexico City to talk about the relevance of this archive. We understood the first step was to promote it. At that time Karen was working at the Universidad Iberoamericana, and, for many reasons, including her important work on feminist art in the art history department, it (the Ibero) became an obvious target.

KCR: I knew of Ana Victoria’s work as a photographer documenting events in the feminist movement. Her photographic work is used in a lot of feminist publications, including some which she was involved in editing, but also from other scholars working on feminism. People knew Ana Victoria had all these photos, though I don’t know if everyone was aware of everything else that is in the archive. I certainly wasn’t aware of its extension before we started working on it.

When we began, the archive was in the house that had belonged to Ana Victoria’s parents, adjacent to her own. It contained boxes of photos, negatives, posters, documents and books. She had begun to digitize the photographs and some key documents related to the feminist movement and the feminist art movement, which made it easy for us to show this material to students and to analyze and interpret it. As we began going through Ana Victoria’s archive, we realized its extension and importance for exploring many different aspects of the feminist movement, the feminist art movement and their connections. And the importance of her photography as artwork, which had only been shown in a few exhibitions but wasn’t known as artwork or appreciated as such.

At the time, Mónica had her Taller Permanente de Arte y Género (TAG) (Permanent art and gender workshop) with a group of emerging artists. I was organizing exhibitions with my art history students. So we came up with the idea of doing this collaboration, activating the archive as an exhibition with our students, and at the same time using that exhibition as leverage to convince the university that this was something very important, and that they should accept it as a donation to the library.

It was an exhibition that showed the importance of the archive and was also the result of a process of intergenerational appropriation of this archive in ways that intermingled history and contemporary art. The project also included students from the Design department who helped recreate objects from the demonstrations featured in Ana Victoria’s archive. Quite a few of the projects shown in the exhibition were interactive, mediating the creative processes with the public.

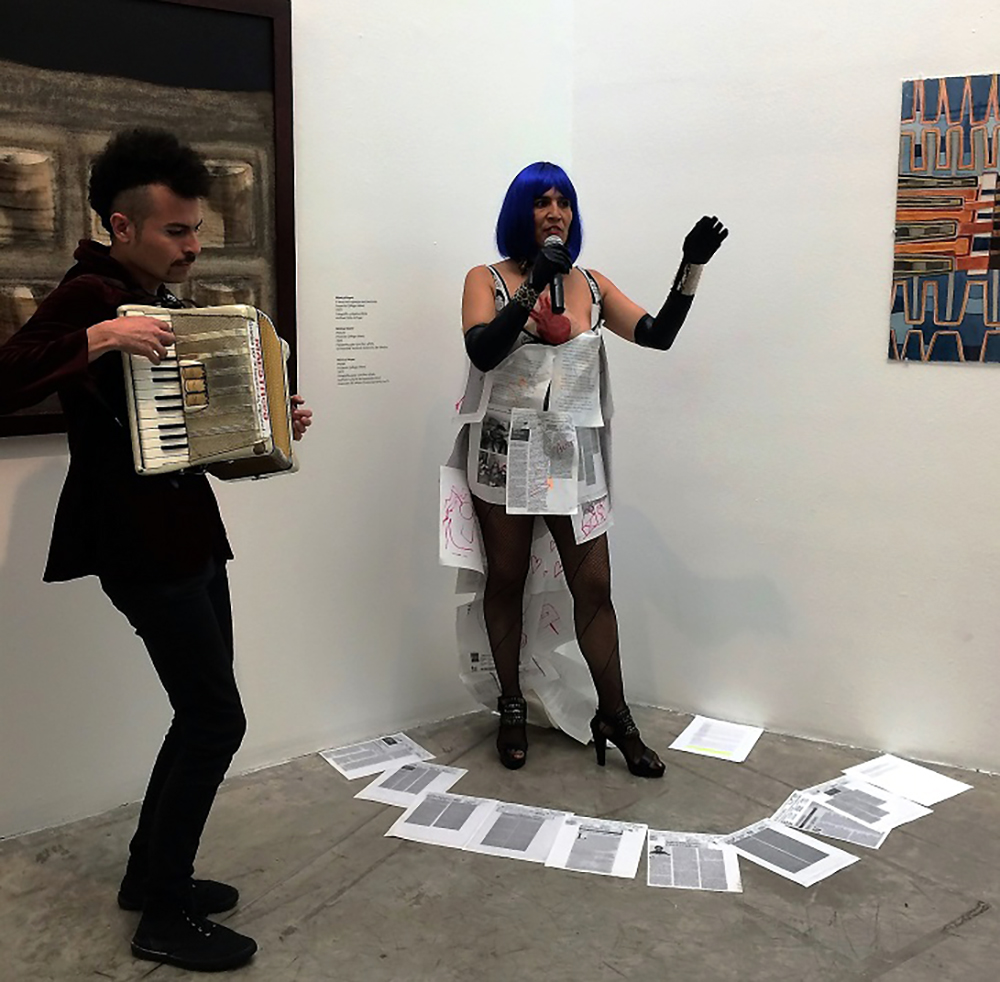

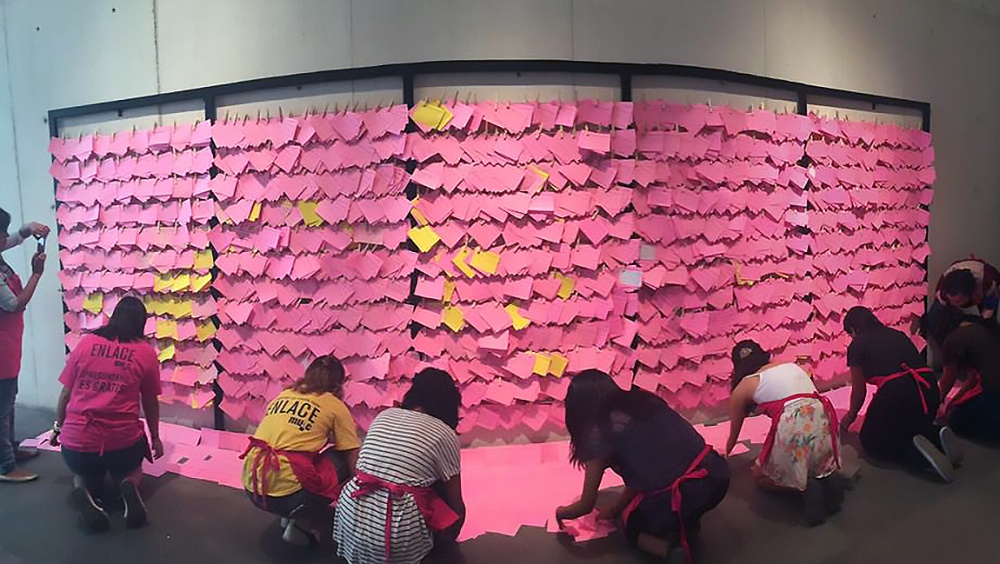

Taller de Arte y Género, De boca en boca (installation view), 2011, from the exhibition Mujeres ¿y qué más? . . ., Universidad del Claustro de Sor Juana, Mexico City, July 2011 (photograph provided by Karen Cordero Reiman)

Taller de Arte y Género (TAG), De boca en boca (Word of Mouth), 2011 (installtion view), Universidad del Claustro de Sor Juana, Mexico City, July 2011 (photograph provided by Karen Cordero Reiman)

Fortunately, we were successful in getting the library to accept Ana Victoria’s archive as a donation. Since then, it’s been a source for many research projects and exhibitions. It’s very interesting that it has become the most consulted archive in the Special Collections of the Ibero library, and also recently recognized as part of the UNESCO program of World Memory in the Mexican chapter.

GA: It is exciting to see your strategy of activation in Ana Victoria’s project, of creating relevance for her archive in the present by allowing people to continue to add to it through their own activations, turning it into a living archive. So, respectively, how did the experience of reactivating Ana Victoria’s archive, through intergenerational workshops, shape your feminist activism and artistic practice, Mónica, and your curatorial practice, Karen?

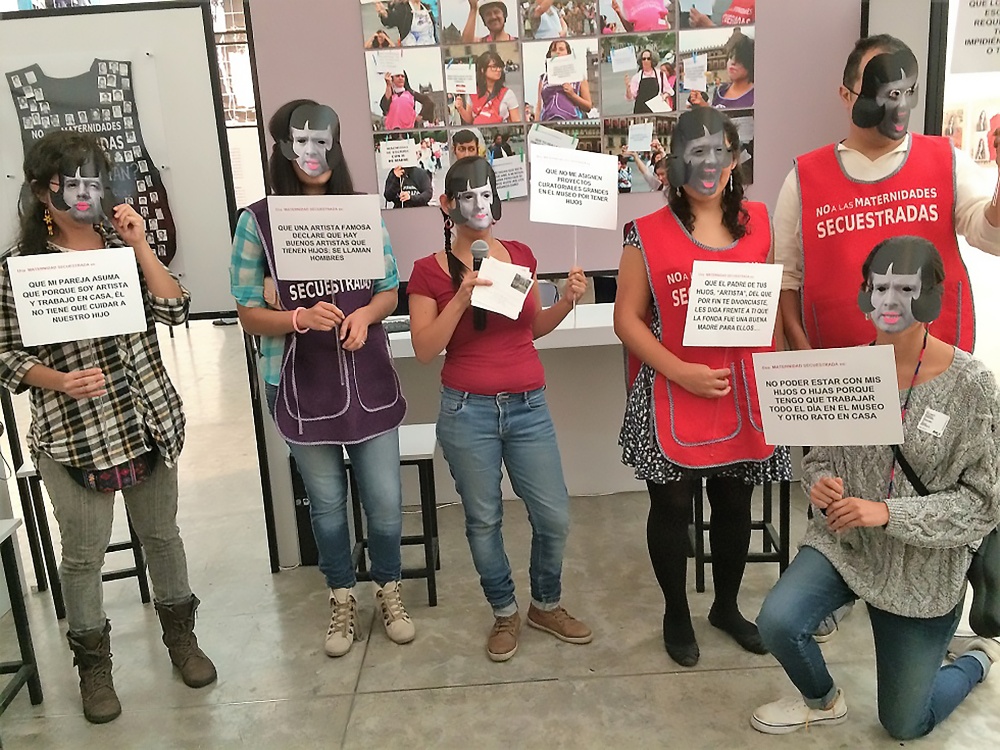

MM: I think this way of working was the result of our earlier experiences. Karen often organized exhibitions with her students and Victor Lerma (Mayer’s artist partner and husband) and I, as (the feminist collective) Pinto mi Raya,4 had been doing art based on archive materials, for years. As you know, we put together an important archive on contemporary Mexican Art, and made many performances based on its contents. However, seeing everybody work with the materials from Ana Victoria’s archive, I felt like doing something with it myself and I began a project called Visita al Archivo de Ana Victoria Jiménez (Visit to the archive of Ana Victoria Jiménez) out of which I developed two pieces: Maternidades Secuestradas (kidnapped maternities) and Archiva: Obras Maestras del Arte Feminista (Archive: Master Works of Feminist Art). These projects, although they don’t include materials from Ana Victoria’s archive, reflect how it is part of my own history, my understanding of feminism and of feminist art.

KCR: Well, for me, it was an important event in terms of working with students, but even more generally, working on curatorial strategies and ways of focusing on art and objects of the past from the standpoint of the present. Mujeres ¿y que más? introduced me to the richness of working with an archive as a universe to be explored. Ana Victoria’s project revealed both a pedagogical and curatorial strategy, working with a specific archive and then building out from there to interrelate it to other types of objects and actions while still having that archive as the center. And, of course, the possibility of giving a home to Ana Victoria’s archive through the exhibition facilitated so many different things, allowing it to realize its potential as a potent source for feminist history, art history and art. That experience consolidated my conception of curatorship as a combination of the choice of objects, mediation, and activation, which was a key element, of course, for the strategies we then put in place and used in Mónica’s “retrocollective” at the MUAC.

BT: Let’s turn to that 2016 retrospective exhibition Si tiene dudas . . . pregunte: Una exposición retrocolectiva de Mónica Mayer (When in Doubt . . . Ask: A Retrocollective Exhibit of Mónica Mayer) at the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporaneo (MUAC), at the National Autonomous University in Mexico City, and how it propelled both of your careers nationally and internationally. Gabriela and I were struck by the idea that it was the first solo exhibition of a Mexican feminist artist curated by a feminist art historian in a renowned Mexican contemporary art museum in the country’s most emblematic public university. In many ways, this exhibition laid the framework for a Mexican feminist curatorial methodology.

Can you tell us about the process of curating the “retrocolectiva/retrocollective” at MUAC together? Were you aware of the potential impact of this show on a new public and in shaping the landscape of feminist art and feminist curation?

MM: Well, Karen knows my work very well and we prepared the exhibition for about a year and a half. A lot of this was talacha (plain hard work), like literally rescuing many of my drawings from where they were stored, cleaning them and getting them photographed. Then we had an intense dialogue about what should or shouldn’t be included. I loved this part because I always learn from her. There were pieces that I would tell Karen, “I don’t like that work, it’s too student-like, lacking technique” and Karen would say, “I think it should be included because it shows the early stages of things you’ve developed since.” We talked a lot. It was great.

Something that was outstanding to me is that, from the beginning, we were both clear that the exhibition was not an end in itself, but a means to something else. It was an excuse to set off different conversations. We knew this exhibition would allow us to dialogue with various communities in the university and beyond. For example, as a parallel event of El Tendedero (The Clothesline; Mayer’s best-known piece), we organized a round table that included academics from the CIEG (Center for Gender Studies) and groups of activists in the university. Although they are all feminists, they don´t necessarily talk. As in La Fiesta de Quince Años, we tried to reach the local audience. We were at the university museum, with a very broad community, which includes high school and university students, staff, workers and academics. So, by bringing hands-on work and having the information go out to the different communities inside and outside the university, we invited them to come. We did the same with the feminist community, inviting women from the SEMILLAS (seeds) Foundation, which is a group that funds women’s projects, feminist groups and older women. We wanted to talk to all of them. The museum did an excellent job of publicizing the exhibition. And I was fortunate because while my exhibition was on, there was also one by Anish Kapoor at the museum, which brought in tons of people. My exhibition received more than one hundred thousand visitors.

In order to reach all these audiences, we had a robust mediation process, including academic events, community outreach and visits to the exhibition. I myself gave more than fifty guided tours, and Karen also gave many. I also did a performance where I would sit at the end of the exhibition, with a sign saying: “If you have doubts (questions), ask” (Si tiene dudas, pregunte), inviting those exiting to sit and talk. The custodians still greet me warmly. They say no other artist has spent so much time at their (own) exhibition. It was very intense work, but it was a lot of fun.

KCR: It was a collaborative process, and I think that was a key aspect. In this case, because we knew each other very well, and we had worked together in so many different contexts, the process of working together and learning from each other was very natural. I learned a tremendous amount just by talking to Mónica, looking at all her works, and documenting all the material that she had accumulated over the years, including her personal archive, her writings, and her publications, all of which form a part of her profile as an artist.

One of the exciting challenges was finding a way to show Mónica’s practice as an integrated interdisciplinary and dialogical process focused both on individual creation and all these kinds of social practices and interactions as a fluid whole. This led to the title “retrocollective,” suggested by Argentine art historian María Laura Rosa, when she commented “this can’t be a retrospective exhibition; it must be a ‘retrocollective’ because of the collaborative nature of much of Mónica’s work.” And, indeed, it was a retrospective exhibition that included works by other people.

MM: Yes, there was work from about sixty other artists in my exhibition.

KCR: Another exciting challenge was figuring out how to display—and in some cases recreate—all the different types of work that Mónica has produced. These included artworks in the traditional sense that you can hang on a wall, but also many process-related objects and documentation of ephemeral pieces: video recordings of performances, objects related to those performances, and artworks that were reconstructed on the basis of the archives of collaborative events. There were also newspaper articles and printed works by Polvo de Gallina Negra (Mayer’s early feminist collective with Maris Bustamante). The challenge for us was articulating and clarifying the status of these different types of works and integrating them into a coherent curatorial discourse.

We wanted an exhibit that captured the dynamic quality of Mónica’s work, not only in the interrelationship of these different levels or types of production and the dialogues they produce, but also in the ways they addressed and involved the public. Building on experiences we had had in the exhibit with Ana Victoria’s archive and others, we activated the exhibition so that the visitors would be involved in it directly, using a variety of strategies so that it wouldn’t be repetitive. The introductory part of the exhibition made this intention very clear. For example, the title of the exhibition, “When in doubt . . . ask” invited participation from the public, as did the Tendedero (an entirely participant-driven work) which grew and expanded over the course of the six months of the show.

There were several ways of activating the works, some very physical, as in the case of Abrazos (Hugs), the reactivation of a performance originally conceived in 2008 by Pinto mi Raya. This piece was based on the description of significant hugs for different people. The mediators invited the public to form a circle, read out those testimonies, and then recreate the hugs. This physical enactment, literally becoming part of a performance, which was near the end of the exhibition, became a very cathartic moment for the participants.

There were many other ways to allow people to participate in the exhibition physically and emotionally. This was important because I have thought a lot throughout my work about the body and the importance of phenomenology in art historical and curatorial practice.5 And, of course, the body and physical involvement is an essential part of Mónica’s practice, Pinto mi Raya’s practice and feminist practice in general. So, we very much wanted to integrate that.

This conviction created specific points of conflict and challenges in relation to the conventional practices and structures of the museum, in terms of how they worked with mediation and conceived the exhibition design. They weren’t used to having both the artist and the curator always being there and actively participating and commenting on everything. But also, I think the exhibition confronted the habitual museum practices because of the complex nature of the different materials shown. Since it was complicated for the museum to resolve their presentation, we did it ourselves or worked with our team to do it. So again, going back to this feminist experience: if you want things to be done in a certain way, it’s best to do them yourself.

MM: One thing I appreciated in the exhibition is how it showed my collaboration both with my teachers and my students. For example, we presented documentation of a piece by Suzanne Lacy (Mayer’s mentor/advisor at the Feminist Studio Workshop) in which I was involved, and also the work by Mexican feminist multidisciplinary artist Liz Misterio inventing nonexistent documentation from La Fiesta de Quince Años. This was very exciting because it underlined the importance of relationships in art and of intergenerational collaboration. But the idea of a retrocollective exhibition was complicated for some people, and they assumed it was all my work, even though we explained the idea of a retrocollective exhibition and each piece had clear information on its author. It was interesting to see how the different levels of collaboration and individual authorship intermingled in the exhibition.

KCR: To answer the question about how the retrocollective exhibition shaped the landscape of feminist art and curation, I think that even though this exhibit built on many things that had been done before, it presented a very public proposal of what a feminist exhibition could be in an important museum of national and international contemporary art in Mexico. This went beyond the content of the show to create a different dynamic, both in terms of its curatorial conception and in terms of its constant activation and the involvement of the artist, the curator and many other people, both individuals and collectives, in that process, echoing the qualities of the works as well as the political conception underlying the exhibition proposal.

MM: And Karen’s idea for the museography was very special, designed to show both art works and documentation of performances and archival materials. Although it was like a labyrinth, wherever you stood you were able to get a view of all the exhibition, and there were small stools all over the space so that if you wanted to read archival material, or watch the videos, you could sit down. And it was flexible enough so we could hold workshops and activate performance in the exhibition space. It was designed for many uses.

KCR: In many exhibitions, the mediation processes with the public are an afterthought. In this case, it was an integral part of its conception. One of my takeaways from the exhibit is that people were touched emotionally and affectively, and involved personally and politically in the exhibition. When this happens, it sticks with them in their memory and in their actions and interactions in a very different way than if it’s just a passive reception experience of someone else’s narrative. So, I think the resonance in that sense, both of Mónica’s work and of the exhibition, have a lot to do with that process.

GA: Because we know retrospective exhibitions are not commonly dedicated to living feminist artists, the critical challenge this exhibition puts forth to the curation of retrospective exhibitions—through how it engages with the public, how it deals with notions of authorship—speaks to a kind of feminist ethic that values working horizontally and intergenerationally. Tracing a connection between the three important projects discussed here, we see how each builds on and complements the other. Do you think of your curatorial, pedagogical art practice and archival work in this exhibition as a model of feminist pedagogy grounded in feminist ethics of collaboration?

MM: For me, it is grounded in feminist ethics, but also strategy. I always think about my work in terms of activism, art and pedagogy because the challenges we face are so complicated, that I try to get a certain synergy going so my projects work on those three levels. Another important axle is the archive, because I believe we are in a battle of narratives, so I understand we have to change those from the past, widen those in our present, and make sure we leave traces so that we are not erased when there is a backlash. I don’t know if this is a model of feminist pedagogy, but it seems to be what worked for us.

It’s part of having un feminismo bien digerido (a well digested feminism), one which isn’t only there theoretically, but is part of how you interact with everyone and everything. I am referring to a feminism that affects who you are and how you work.

KCR: With these three projects, we began intuitively and consciously developing a concept of feminist curatorial work as activism, which is one of the cornerstones of both Mónica’s practice and Pinto mi Raya’s practice.

I personally continue to clarify my ideas with respect to this and have tried to create a provisional theory on the basis of these experiences in order to transmit them to other people both in workshops and classes and through lectures and texts.

They also have influenced the practice and pedagogy of feminist curatorship in Mexico. For example, after Mujeres ¿y que más? Chilean performance artist and scholar Julia Antivilo developed a feminist curatorial workshop in which participants went to the archives of various feminist artists and then organized an exhibition, presenting and activating those archives. Marisol García Walls, a co-curator of Mónica’s current exhibition in the state of Veracruz, Hija de su Madre, was one of the participants in that workshop.6

There’s been a lot of discourse lately about care related to feminism, and I think seeing an exhibition not just as something you inaugurate and then leave to its own devices relates to these discourses. Thinking that an exhibition will do its work by itself is problematic. I think (as a feminist curator) you must be there, assuring that the exhibit does the job it’s supposed to do and forming a part of that process because, in most cases, the museum structures won’t do it, and the ways in which visitors are used to experiencing exhibits are based primarily on a passive model. I think our obsessiveness with being involved in Mónica’s exhibition through public programming and dialogue, as Mónica mentions, of thinking of the exhibitions as processes and actions rather than ends, is still a critical aspect that must be integrated into artistic and social practice and even in the field of study of the public and evaluation of exhibits, which at least in Mexico is still nascent.

BT: To conclude, then, both of you have been at the forefront of feminist art in Mexico, making it, archiving it, curating it, recording it, and historicizing it. We have already seen some changes in the culture in terms of feminist art’s reception and embrace.

For example, Karen, the 1975 exhibitions in Mexico City celebrating women in art were more about women as subjects than about women as artists. Nearly fifty years later, you curated a show very much about women artists from the Museo Kaluz collection—(Re) generando . . . narrativas e imaginarios. Mujeres en diálogo ([Re]generating . . . Narratives and Imaginaries. Women in Dialogue), October 2022-April 2023—curated and conceived through a feminist lens. This show generated an astounding amount of interest among critics and the general population.

And, Mónica, in recent years, you’ve received strong institutional recognition for your work, including the Medalla Omecíhuatl, from the Mexico City Women’s Institute, and the Medal of Fine Arts from the National Institute of Fine Arts and Literature in 2021, among others (including the CAA Distinguished Feminist Artist Award, 2025). Embrace and appreciation of your work, especially El Tendedero, has expanded nationally and internationally; this is a significant change from the mid-1970s, when, as you have written, your work was literally thrown in the trash by some of your classmates.

What changes have you seen regarding public and critical response to feminist art and curatorial practice in your time, and what might that indicate for the future?

MM: I always mention that when we started doing feminist art, nobody wanted to play with us. Today there are tons of collectives; all sorts of feminist art, feminist theory, feminist theatre, dance, music, zines and performances. But its not just the fact that there are more feminist artists. I find that the younger generations have incorporated art as a basic tool for activism. I am thinking of works by LASTESIS,7 Elina Chauvet,8 or my Tendedero (Clothesline), which are works by artists that they have made their own.

I think recognition as an artist is important because it’s a way of opening the door for others. As Karen mentioned during her speech at the opening at the MUAC: “It’s great that this exhibition is opening today, but the whole point is that it is the first of many.” I’d hate to be the “token” woman artist.

KCR: I agree with Mónica that there has been a change in the context. Feminism has become a mass movement, particularly in Mexico and Latin America, and cultural and artistic aspects have become a more integral part of that process. This is a crucial change, which contributed to the possibility of having Mónica’s exhibit at the MUAC, and many other exhibitions related to gender issues and other previously unmentionable issues in public contexts. This change over time was propelled by the feminist movement and its interrelationship with other movements, giving voice to experiences which previously were not visible or were deliberately marginalized in terms of social visibility. This transformation created conditions of possibility for other exhibitions, like the exhibition at the Museo Kaluz that you mentioned, Bárbara. Over the years, I’ve been involved in various exhibition proposals, which were purported rereadings of collections from a gender perspective. Several of them never came to fruition for different reasons. Maybe the time was not ripe for that type of institutional critique, self-critique, or contextualization of collections from that standpoint. But today, it’s possible.

So now, we may be facing a different challenge. Maybe there’s a saturation, an explosion of exhibitions, publications, and visibility of gendered discourses. This is something, of course, that I celebrate and consider essential. Still, we must be wary of whether this visibility will have consequences for more profound structural changes, in the art world and, of course, in society in general. For all the hundreds, or perhaps thousands, of Tendederos that have been created, we still have an index of gender violence and feminicide9 that’s increasing every day. So, we must continue to demand structural changes.

Also, I would like to underline the importance of dialogue and collaboration in all these processes, as well as solidarity and sorority. Those are the key terms for my work and the possibility for survival of our society, moving forward. For me, as someone who was a university professor for thirty two years, it’s gratifying to see how many of my former students are working on feminist content and creating contexts for feminist dialogue in different positions, as teachers, in museums, and as artists.

MM: In Mexico, whenever I see that a museum is showing more women artists, I check who is the director. And yes, it is often one of Karen’s students.

BT: It is challenging to see how groundbreaking you are when you are the ones breaking the ground. But we have evidence in everything you’ve said today about your work, your actions, and your development of pedagogies and feminist curatorial ethics. You laid the groundwork that has allowed what you’ve begun to not only grow but to blossom, and it continues through the people you’ve trained and taught, and whose world view you’ve opened. I just wanted you to see that from our perspective as well.

MM: Bárbara, thank you for what you just said; I am glad it has worked.

Karen Cordero Reiman is a US-born art historian, curator, and writer based in Mexico City since the 1980s. She has had a long career as a university professor and is the author of numerous publications in her areas of specialization, including twentieth- and twenty-first-century art; the relationship between the so-called “fine arts” and “popular arts”; and body, gender and sexual identity. She has also had a continuous participation in museums as curator, advisor, and researcher. Currently she works as an independent researcher and curator, and on personal creative projects that relate art, literature, and history.

Mónica Mayer is a pioneer in feminist art in Mexico. Her work combines performance, drawing, writing, teaching, and community participation. In 1983, she co-founded Polvo de Gallina Negra, the country’s first feminist art group. She is best known for El Tendedero (The Clothesline, 1978), reactivated globally in recent years. Mayer has participated in major international exhibitions such as WACK! and Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985.

Bárbara Tyner is a writer and art historian specializing in women’s art history of twentieth- and twenty-first-century Mexico, and feminist art and activism in Latin America. Educated in Los Angeles, New Mexico, and Mexico City, she divides her time between Mexico City and Kelowna, BC, Canada, where she is a lecturer in Latin American art at the University of British Columbia.

Gabriela Aceves Sepúlveda is an Associate Professor in the School of Interactive Arts and Technology at Simon Fraser University. Her research delves into the histories of women and feminism(s) at the intersection of art, media, science, and technology, with a special focus on Latin American women artists and research-creation. She is the author of the award-winning book Women Made Visible: Feminist Art and Media in post-1968 Mexico (2019).

- “Best of 2016: Our Top 15 Exhibitions Around the World,” Hyperallergic, December 30, 2016 ↩

- The other two feminist art collectives active at the time included Polvo de Gallina Negra (1983–93), organized by Mayer with Maris Bustamante and for a few months Herminia Dosal, and the Colectivo Bio Arte with Nunik Sauret, Roselle Faure, Rose Van Langen, Guadalupe García, and Laita, also beginning in 1983. Other collective feminist efforts included those of artists Magali Lara and Rowena Morales with writer Carmen Boullosa. See Gabriela Aceves Sepúlveda, Women Made Visible: Feminist Art and Media in Post-1968 Mexico City (University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 174–75. ↩

- “Tlacuilas y Retrateras,” Fem 9, no. 33 (April–May 1984): 41–44. ↩

- Pinto mi Raya (PMR) (I draw my line), is the ongoing collective and archival project Mayer initiated with her husband artist Victor Lerma in 1989, initially as an experimental gallery space. PMR strategically addresses social institutions, taking on the art system in Mexico, personal boundaries, nationalism, art collecting and the art market, and documentation. ↩

- Cordero Reiman was the chief curator of the 1998–99 exhibition El cuerpo aludido. Anatomías y construcciones. México, siglos XVI–XX (Allusions to the Body. Anatomies and Constructions. Mexico, Sixteenth through Twentieth Centuries), at Mexico City’s National Museum of Art (MUNAL), focusing on representations of the body and its signification in different contexts in Mexico. ↩

- The exhibition opened at the Exconvento Betlehemita in the city of Veracruz on April 4, 2024, and in Xalapa, at the Galería de Arte Contemporáneo of Xalapa, July 4, 2024. ↩

- The Chilean collective’s performance Un violador en tu camino (A rapist in your path) gave voice and dance moves to a global feminist outcry against gendered violence, going viral beginning in 2019. ↩

- Mexican feminist artist/artivist Elina Chauvet (b. 1959) investigates the relationship between social processes and violence toward women through works such as the gripping Zapatos Rojos (Red shoes), a collaborative public art project she began in 2009 in Ciudad Juárez, featuring the placement of hundreds of pairs of empty shoes, each painted red by volunteers, placed together in an open public space, such as a plaza, street or square. Zapatos Rojos has been replicated in several Mexican cities and in many countries. ↩

- The term “feminicide” (feminicidio) is used standardly in Mexico and Latin America to indicate more than femicide, the killing of women for being women, to convey a political component implicating not only perpetrators but also the state and judicial structures normalizing misogyny. ↩