How do you tell the story of an arts program? How do you capture the learning process in a way that is useful to other practitioners and commissioners? Case studies? Evaluation reports? Tool kits? Or can art itself act as a teaching mechanism? Can we capture and share learning through creative work? These were the questions I considered when I replied to an open call to creatively evaluate the first three years of the Creative People and Places (CPP) program. CPP is an Arts Council England initiative that invests significant funding and support in twenty-one places across England with low arts engagement historically, to enable local people to take the lead in choosing, creating, and taking part in brilliant art experiences. Projects range from a brass-band commission in St. Helen’s town center, to ceramic-making workshops on an allotment in Blackpool, to a light festival bringing to life a suburban park in Doncaster.

CPP is a program designed to change how participatory arts are commissioned—involving local people in the process from the very beginning and arguing for the value of the arts in our lives. The CPP network felt strongly that inviting artists to assess the program demonstrated this commitment to and belief in the arts and would offer a distinct perspective on the program. I asked Holly Donagh, chair of the national steering group for the first phase of CPP, about the network’s decision to commission the “creative” evaluation alongside a more traditional evaluation. She said:

As someone with a strong interest in research, who is often critical of the quality of research produced by the arts sector, I was skeptical of the value of an arts-based approach to evaluation, and it took a number of discussions at the national steering group to agree to this approach. I now feel that the most authentic record we have of the last three years of CPP is within More Than 100 Stories, and it has managed to capture the essence of the program in a way that more technically rigorous evaluation cannot.1

Our commissioners, while initially reluctant, were ultimately convinced that an artistic evaluation was able to capture the energy, passion, and occasional magic of the program, and in a way that the more technical reports were not.

I was awarded the commission along with visual artist Nicole Mollett. We both have our own socially engaged practices: my work as a writer focuses on people’s relationship with place and on amplifying voices often ignored by mainstream society; Nicole also explores place, with an emphasis on mapping and on communities in areas undergoing regeneration. We were both drawn to CPP’s ambition to revolutionize how art projects are designed, commissioned, and delivered, with a goal of increasing community participation from projects’ early stages and building strong lasting partnerships with communities and places.

We were also interested in CPP’s commitment to experimentation, evaluation, and implementation of changes based on learning. The program’s architects recognized that for an initiative attempting to fundamentally change how arts activity is designed and delivered in places with traditionally very low arts engagement, those managing the projects needed to be encouraged and enabled to try new ideas—and, more importantly, to admit to and learn from failures.

And, finally, we were both excited by the commission’s invitation to create new work in response to the CPP program—to find a way to say something meaningful in the realm of evaluation about the program that would also stand on its own as art.

Approaching the commission

Nicole and I were somewhat intimidated by the prospect of trying to make a piece of art in response to such a huge program, one spanning twenty-one large-scale arts-led projects from Northumberland to Kent, Blackpool to Boston. The commission was substantial, but not huge, and though between us we visited each place and were in touch with program directors and staff on the phone and via email, there was no way we could genuinely understand the successes and failures of each and every element of each and every project.

We were also uncomfortable with the idea, inherent in the term evaluation, of passing judgment. We were excited about exploring the stories and the learning of the program but did not want to put ourselves in the position of saying that specific projects were good or bad. We didn’t feel qualified or informed enough to do so. More importantly, we didn’t feel it was beneficial or relevant to what we were trying to achieve. We wanted to create work that looked critically and reflectively at the issues and challenges faced by CPP without singling out projects for praise or criticism. Our aim, right from the start, was to ask questions and invite others to do the same. We were particularly interested in the kinds of questions that often get brushed under the carpet with participatory work: What does it mean to fail? How can we talk helpfully about failure? How can/should we talk about art with people who have little or no experience of it? Whose voice really matters? Where does the power in these kinds of projects really lie? We tried to answer these questions by asking deliberately open and provocative questions, and by listening hard to what people chose to tell us.

Our approach

Nicole and I also committed ourselves to creating a lot of work, and we were keen to build together a body of work that would tell a larger and more complex story than a single piece would be able to. Our title was also informed by the decision to make the final piece an online collection, one that was easily accessible and could be navigated thematically, rather than in a linear fashion.

In titling the work More Than 100 Stories, we voiced our commitment to tell a range of stories about the CPP places and projects we visited and learned about. Many of the places I visited, such as St. Helen’s, Doncaster, and Burnley, are in the north of England and blighted by industrial decline—places that once had strong identities built around mills or mines but are now struggling with unemployment, apathy, and a belief that they are forgotten. I felt a strong sense of responsibility toward these places: to represent both their problems and their often hidden potential.

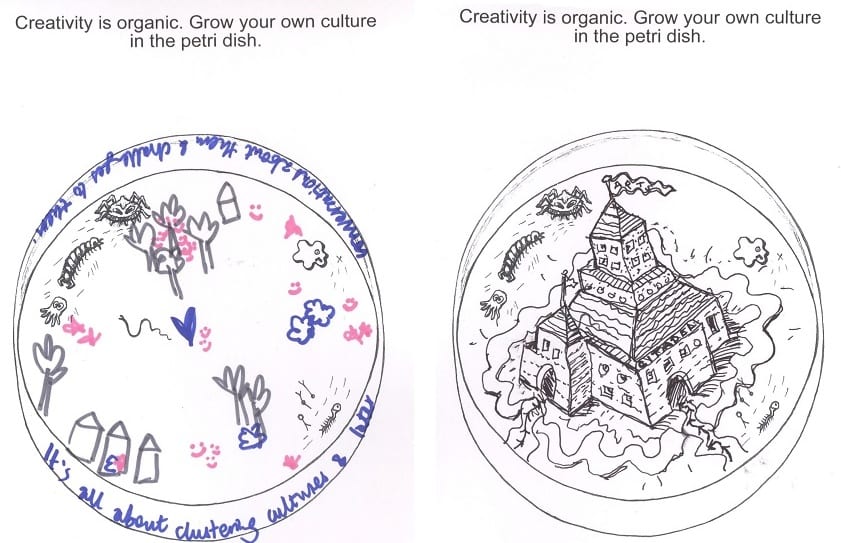

We started with a set of deliberately open-ended questions, to start growing and developing our understanding of CPP. Nicole created hand-drawn postcards that posed these questions and invited drawings in response to prompts—for example, “Draw some art and something that is not art”; “Creativity is organic. Grow your own culture in the petri dish.” These cards were disseminated at CPP conferences and posted to each project with an invitation to project directors to distribute them among staff and participants.

Acknowledging the fact that we would never be able to get completely under the skin of each project, we started to look for commonalities and connections across the projects. We initially extracted ten key themes, which later structured a thematic list of questions that we distributed to project administrators through online surveys and email and phone conversations. Some examples follow:

- What difference do people’s personalities make to your team and your project?

- How would you describe the networks and connections that have been made between people as a result of your CPP project?

- We often talk about “real people” in conversations about the arts. What does that mean? Who are your “real people”?

- Do you try to appeal to a range of tastes?

- Whose taste is reflected in the work you commission?

- Is there any snobbery in your CPP project? If so, how does it manifest itself?

- How do you listen to local people?

- Does offering a narrative around a piece of art help or hinder? Does it erect more barriers or does it help people contextualize?

- Does everyone involved in your CPP project speak the same language? If not, how do the languages differ? How do you translate?

Having collected as much information and evidence as we could from over 250 people over the course of a year, we started to make our work. For each theme, we made our own individual pieces and one joint piece, bringing together images and words. These were presented on a digital platform, the website More Than 100 Stories, as text pieces and hand-drawn images. We also created a piece of print: a large foldout copy of Nicole’s map of England that celebrates each CPP project, with a short story on the opposite side. Together, the pieces build a mosaic of information, provocation, and celebration around the diverse work undertaken. Below is a small selection of pieces from More Than 100 Stories.

Living Room

Living Room is an example of a piece written in response to a specific project, riffing off of a conversation with project staff. Through Heart of Glass, the CPP project in St. Helen’s, people could apply to have members of the BBC Philharmonic play in their homes. The piece imagines one of these events, capturing the emotion of the moment and the pleasingly disruptive experience of a usually public event invading a domestic space.

When she was ten, her teacher brought a record player into class. Listen to this, he said, this is real music—this is the BBC Philharmonic. She couldn’t tell you what the music was called, but she remembers feeling as though her heart had flooded. Other people might have bought their own records, gone to concerts; she knows that, but somehow she could never work out what to buy or where to go.

Now she’s sixty, and there are four musicians in her living room. Violin, viola, cello, double bass; she says their names over in her head. Two men in black tie, two women in long dresses, as though her house is the Royal Albert Hall, not a terrace round the back of Asda. The family’s all there, and half the neighbours—even old Mr. Maplethorpe, who’d snorted with laughter when she invited him.

A violin, viola, cello, double bass—in her living room. She’s spent a week tidying up: even washed the curtains and cleaned the windows inside and out; polished the sideboard they inherited from Jim’s mum and every last plate and ornament on it; arranged the family photos in a neat diagonal across the mantlepiece. The musicians are on dining room chairs by the window and the rest of them are squashed onto the sofas—the young ones on the floor. The man who started the whole thing off is down there too, hugging his knees to his chest. I couldn’t do that, she told him when he’d asked, not me. And he’d said, why not? Which isn’t a question she’s ever thought about much.

They are raising their bows now, and the air is taut and sparkling with the moment before they begin. And here, again: the music like liquid silver in her veins.

Let Them Eat Cupcakes

Let Them Eat Cupcakes is an example of a more abstract piece, captured in a single image and inspired by a comment from Laurie Peake, director of the Burnley-based CPP project Super Slow Way, at a conference in Liverpool in 2016. She was describing a project called “Home baked,” unrelated to CPP, that took place in Anfield, Liverpool. It was a collaborative effort to reopen a family bakery called Mitchells, which had been running for many years near the local football stadium. The idea was to turn it into a training center and community bakery. Conflict arose during a discussion about the kind of products the shop should make and sell. Some members of the group wanted to produce cupcakes, while the project’s creative team was against this idea on the grounds of maintaining the healthy, traditional identity of the bakery. This story revealed to us the potential for misunderstandings between artists and communities in a way that directly related to many of the CPP projects. It raised questions like these: Who decides the details of an artwork? Who gets the final say—the artist or the community participants? Where does authorship lie? Who gets to decide what is good taste? The project’s title riffs on the phrase “let them eat cake,” attributed to Marie Antoinette, which supposedly revealed her privileged obliviousness regarding the diet of the poor and their access to food.

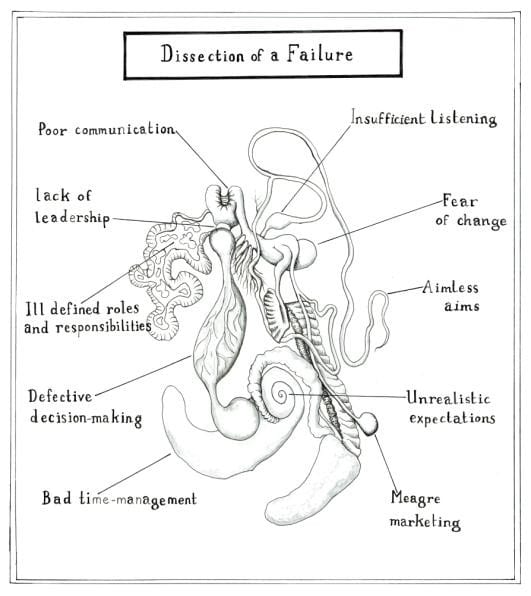

Dissection of a Failure

Dissection of a Failure is a playful response to our conversations about failure. I came up with a list of reasons that had commonly been cited for failure, and Nicole used it to label the anatomy of a slug.

Sarah Butler and Nicole Mollett, Dissection of a Failure, 2016, pencil drawing, 11 3/4 x 13 3/8 in. (30 x 34 cm), from More Than 100 Stories (artwork © Sarah Butler and Nicole Mollett)

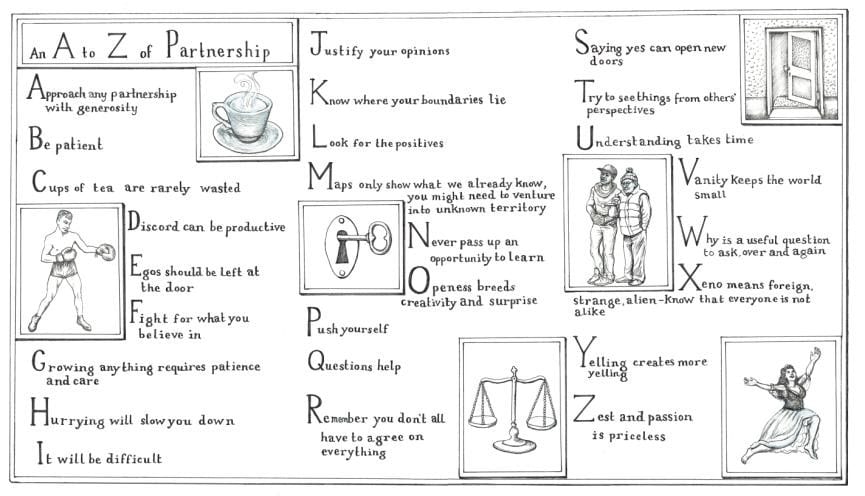

An A to Z of Partnership

An A to Z of Partnership is another joint piece, again playful, this one taking a look at the elements of successful partnership.

Sarah Butler and Nicole Mollett, An A to Z of Partnership, 2016, pencil drawing, 18 7/8 x 11 in. (48 x 28 cm), from More Than 100 Stories (artwork © Sarah Butler and Nicole Mollett)

Creative evaluation

We entered this project wondering how we would balance the two sides of the phrase creative evaluation. How would we make new work that had value in and of itself and that also said something meaningful about the CPP program?

We were both searching throughout for ways to share our understanding of CPP—for ways to make work that referred to the specifics of CPP but also opened up wider questions for arts practitioners and commissioners. Many of Nicole’s pieces include images of CPP participants and staff. Much of my own work refers to specific stories told or observed about specific places. And yet we chose not to name either people or places, partly because we didn’t want to get trapped in the bind of trying to “fairly” represent each project, but mainly because we wanted audiences to look for the universal in each piece, to reflect on how it might apply to different places and people.

This was a fascinating and challenging commission: trying to do justice to the rich complexity of the CPP program; trying to balance the connection and passion required to build relationships and make art with the objectivity required by an evaluation; trying to make work that stood on its own and also said something meaningful about CPP. And I would argue that the pieces Nicole and I created do stand on their own as art, art that—as all good works of art do—invites its audiences to think, to question, to look at the world differently.

I sometimes find myself wondering if More Than 100 Stories is more an exercise in storytelling and representation than an essay in evaluation. And yet it isn’t just representation; it is an attempt to find ways—accessible, engaging, playful ways—to talk about the bigger issues raised by the CPP program: How do we talk and think about failure? How do we respond to specific places—their histories, communities, geographies? How do we find ways to speak clearly and truthfully about art? Can we genuinely democratize the process of commissioning art, and what does it mean if we do?

An Impossible Glossary

I end with an offering: An Impossible Glossary explores and satirizes the language used in arts programs such as CPP. I have found, during this project and in my own previous work as a practitioner, that words can become bleached of meaning through overuse. An Impossible Glossary is an attempt to reclaim the richness and poetry of the words we use to talk and think about art.

A list of practical, problematic terms—used within the Creative People and Places programme—and their contradictory, shifting, uncertain meanings

Activity- The thing that must be done, measured, reported upon

- Something to be argued about (see Quality)

- A matter of class

- From a Latin root, meaning “put together, join, fit.” Its first definition in the Oxford English Dictionary is “skill as the result of knowledge and practice.” It is not until the third definition that we get a mention of the “application of skill according to aesthetic principles.”

- A place filled with hope

- Feared. Resisted. Fought for.

- Involves loss. Promises gain.

- Often referred to in funding applications (see Funding)

- The thing that will save us

- A group of people with some connection, either self-selected or imposed by circumstance

- A desired state

- A nostalgic term for something lost

- Something we want to (are paid to?) engage with (see Engagement)

- A term used by those with power in relation to those without power (see Community)

- When the money runs out

- When the energy runs out

- When we have made ourselves superfluous

- When there’s nowhere else to go

- One person’s end is another’s beginning (see Beginning)

- It happens to us all

- A contract, involving love and commitment and time (often initiated by one party kneeling before the other)

- A term used to describe something done often (see Practice) but not valued (see Value). Has the capacity to be extraordinary (see Extraordinary)

- An insult

- Something to be remarked upon

- Not something you see every day (see Everyday)

- Something to be remembered

- An insult

- That’s the million-dollar question

- How far are you prepared to walk?2

- An action, often repeated

- The journey from A (no project) to Z (end of project). (See End and Project)

- A unit of measurement for something that keeps changing its shape

- A nest of vipers

- A booby trap

- Something to be argued about (see Art)

- Something to be missed, lost, stretched to breaking point

- Why do we do what we do? What is the point? Where is the gold?

Sarah Butler explores the relationship between writing and place through prose, poetry, and participatory projects. She is the author of Ten Things I’ve Learnt about Love and Before the Fire (both Picador) and the novella Not Home, written in conversation with people living in unsupported temporary accommodations in Manchester. Her new novel, Jack and Bet, will be published by Picador in spring 2020.

www.urbanwords.org.uk | www.sarahbutler.org.uk