From Art Journal 78, no. 3 (Fall 2019)

Fantasies of a better tomorrow are frequently bound up with technological advancement. Indeed, these are often mutually affirming.1 Too often, though, devices are readily incorporated into daily life without the social or political transformations needed to realize the promises publicized on their behalf. New tools of production proclaim an opening up of possibilities but merely reproduce existing conditions. As Bertolt Brecht put it when pondering the revolutionary potential of the radio as an apparatus of communication, they “renovate ideological institutions on the basis of the existing social order by means of innovation.”2 Fantasy remains mere image, dissociated from experience, from an encounter with the relationship between that which is and that which could or ought to be. It preserves the present as reality rather than transforming it.

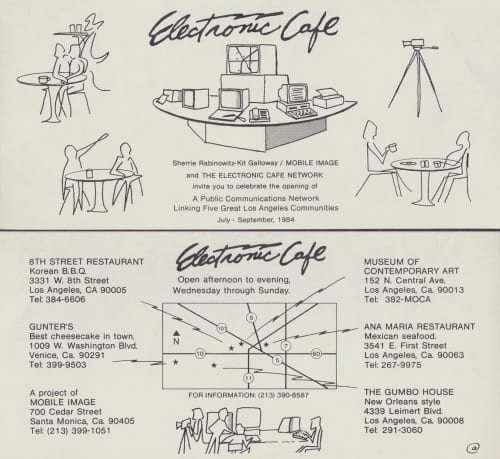

During the summer of 1984 the art-activist group Mobile Image operated Electronic Café, an elaborate network of telecommunication productions spread across the city of Los Angeles. The project politicized enduring myths of technological innovation and engaged fantasy in an exceptional way—as pedagogical and organizational process rather than imagination-as-product. Over a period of seven weeks, members of particular publics vied over psycho-geographic territories. They appropriated mass-media transmissions and archived memories, plans, and encounters—some banal, others activist. Eschewing symbolic celebrations of connectivity, Electronic Café sought to facilitate a struggle with the mediation of subjectivity. The work modeled what Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge, in their examination of the postindustrial public sphere, called “the workings of fantasy as the form in which authentic experience is produced.”3 Here fantasy is the productive alignment of specific social needs and desires, critical consciousness, and the outside world.

Electronic Café contended with a surge in media populism, as corporate, artistic, and activist campaigns offered complementary visions of personalized liberation and gratification through emergent technologies while postmodernist critiques presented pessimistic accounts of a thoroughly mediated society. The work must be understood within a specific material, artistic, and discursive constellation of persistent techno-myths, rapid advancements in telecommunication hardware, and the politics of perception as a contest over the notions of ownership, access, and participation. Electronic Café was part of an ongoing struggle over the formation of social imaginaries and the political economy of tools, a struggle whose numerous manifestations include science-fiction novels conceived as instruments for the liberation of utopian consciousness and the electronic consumer industry’s peddling of personal computers and personalized infotainment devices. It likewise must be understood in relation to a range of past, contemporaneous, and subsequent art, including the “art and technology” programs of the late 1960s and early 1970s and the era’s broader conceptual art movement, the various forms of telecommunications art that arose over the following decade, and the emergence of early internet network projects and relational aesthetics in the 1990s.

Neither embracing new technologies as panacea nor rejecting them as solely mechanisms of spectacle, Mobile Image modeled an arrangement that was then, and still is, highly unusual: Electronic Café made palpable the workings of the tools that project and are projected on, creating not individual but social moments of awareness in which users could recognize where the making of meaning and knowledge prevails, fails, or expands. Its network facilitated the negotiation of the ideal and the real, the ideological and the material, the dominant and the alternative, not as opposites but as components of a relational field made up of overlapping publics that, to varying degrees, shared experiences of deviation from traditional notions of identity and encounter. Setting aside confining, corporate-driven illusions and fetishized notions of technology as a direct path toward a fanciful future perpetually just out of reach, Mobile Image enabled fantasy to work as what Negt and Kluge call an “organizer of mediation,” an intervention capable of influencing the direction and structure of techno-social progress. Electronic Café thus examined and critically (re)enacted the relation between mass communication and the personal wielding of high-tech machines; between public media, interest groups, and popular desires; between the fragmentation of canonical histories and identities and the niche marketing of unique selfhood; between the dematerialization of experience and spectacles of consumption. What was innovative about Electronic Café was not the technology as such, but the critical assessment of present productive conditions and latent possibilities applied to the construction of a reimagined future.4

Though largely overlooked in the art historical record, Electronic Café and its lessons are especially relevant today. The work modeled a practice that appropriates the possibilities of digital global technology while consistently putting that technology into action and to the test. As fantasy, this practice productively applies and critically reflects on the possibilities and limits of evolving communication technologies, forming and re-forming counterpublics as sites of discursive and performative agency.

Electronic Café

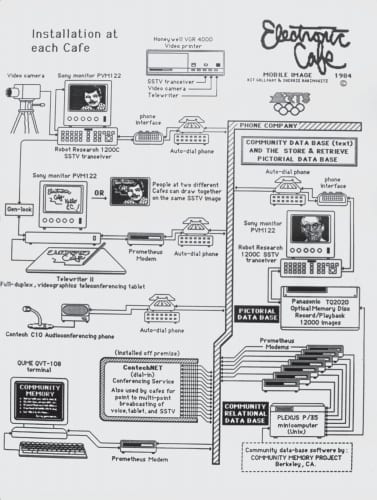

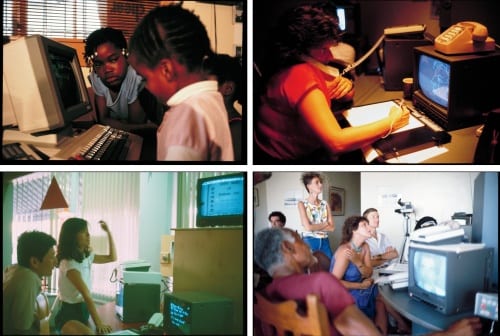

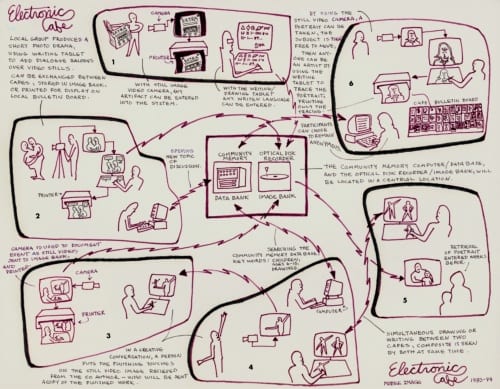

Conceived and implemented by Mobile Image’s cofounders, Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz, Electronic Café linked public locations in five different Los Angeles neighborhoods: South-Central (now called South LA), East LA, Koreatown, Venice Beach, and Downtown LA. Each site in this “telecollaborative network” was equipped with an array of communication devices that were futuristic for the time—a computer messaging system, searchable text and pictorial databases, image-exchange and audio-conferencing equipment, slow-scan television cameras, digital writing and drawing tablets, and high-resolution printers—all made available to local residents. Visitors could post text and images, participate in conversations, appropriate and manipulate material from both mainstream media and users at other café sites, record and archive memories, histories, and encounters, and search and retrieve contributions from the expanding database. This ambitious project was part of the Olympic Arts Festival, a citywide multicultural celebration of “international brotherhood” meant to exemplify the spirit of the Olympic Games, hosted by Los Angeles that year.5 Operating six hours a day for seven weeks, the project encouraged participants to use telecommunication technologies to critically engage the material and immaterial connections and divisions that existed across this notoriously sprawling and fragmented city.

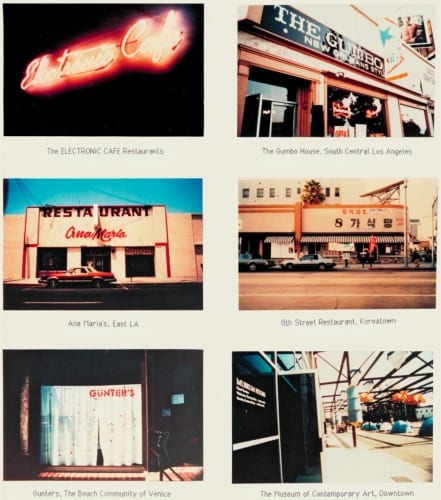

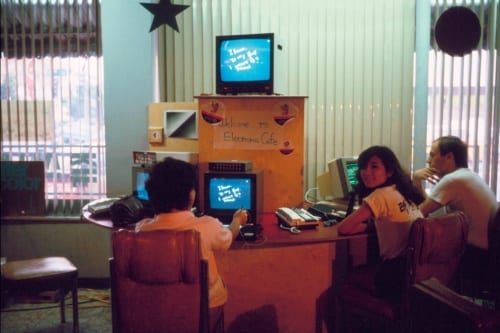

Mobile Image designed Electronic Café to simultaneously underscore current conditions and inspire future-imagining, placing the two in dialogue. At each locational node the available telecommunication equipment was set within a self-contained semicircular console. Its streamlined, monochrome design and precise arrangement of devices—several small monitors and workstations below, with a large screen overhead—evoked control panels featured in countless science-fiction movies and television shows. Yet Mobile Image took care to prevent its sci-fi aesthetics and machinery from operating in isolation: the network was emphatically grounded in the specificity of the sites that comprised it—the various neighborhoods of Los Angeles, the identity labels conventionally affixed to them, and the particular establishments in which the futuristic consoles were installed. Four of the five locations were restaurants, selected by local residents collaborating with the artists because they were firmly rooted in their respective communities. The East LA node was installed in Ana Maria, an “all-Mexican” family restaurant with waitresses wearing traditional dresses and murals featuring colonial architecture.6 South LA’s was located in the Gumbo House, a Cajun restaurant catering to the local African American population. Koreatown’s was in the 8th Street Restaurant, described by artist-participant Hye-Sook Park as “a very rural, Korean-only restaurant.”7 The Venice Beach location was Günter’s, a bohemian eatery modeled on the traditional coffeehouse and intended, according to its owner, as “a forum for the arts and serious political discussion.”8 The fifth site was the Museum of Contemporary Art, which functioned as the project’s pointedly institutional arm. Electronic Café encouraged users to observe and consider the relations between the immediate social reality of their locations and the technological apparatus at hand.

To further encourage this dialogue, Mobile Image consciously limited itself to then-current technological capabilities. The fantastic devices that comprised Electronic Café were state-of-the-art but not speculative; despite their technical know-how, the artists chose to employ off-the-shelf equipment and “narrowband” networking via preexisting telephone lines rather than build new prototypes that would not be available for years. Nonetheless, most of the featured equipment was still relatively unfamiliar to the general public. The point was to allow users to actively participate in the development of the still-unformed protocols and parameters of emergent technologies without getting overly distracted by or enamored with the machinery itself. Mobile Image also carefully constructed the consoles so that the complexity of the devices—the elaborate wiring and networking mechanisms—would be largely invisible, rendering the system as user-friendly as possible. As Rabinowitz explained, participants “were confronted with about $70,000 worth of equipment in each café, but the technology was transparent enough that they came away with the quality of the human experience they had.”9 Each location also had an “artist-in-residence” with existing ties to the local community and the technical know-how to demonstrate the capabilities of the network and encourage participants to improvise.

Many of the project’s myriad visual and textual manifestations were contained by its computerized bulletin board system (BBS). A customized version of Community Memory—the first public BBS, established in the mid-1970s in Berkeley, California—combined with a digital image bank, the platform allowed users to post text and pictures that could then be retrieved and commented on by other users. This not only enabled an exchange of information but also formed a cumulative, searchable database that could serve as a space for public interaction and identity formation according to the particular needs of the user—not as an autonomous individual, but as a social being with shareable concerns. It was explicitly designed to function as a flexible archive, a site for collecting alternate histories, and an arena for fresh forms of political organization.10 Mobile Image was especially drawn to this customizable, thematically based filing scheme that could incorporate a potentially limitless multiplicity and combination of ideas and issues—high and low, public and private. The system came with a set of preprogrammed general “index words” (e.g., music, food, sex) and additional words geared toward historically specific, local and translocal concerns (e.g., housing, nuclear, women), but it was also enriched by any number of user-generated categories (e.g., “media for peace,” “American Regime,” “the life of a refugee,” “transsexual rights,” “what it takes to be in the public”) entered on-site. In this way the network enabled new social formations via common and negotiated values and interests beyond preconstructed labels. It presented additional opportunities to produce heterogeneous relations, and to recognize the power of doing so.

Initially, interactions within the network tended to be characterized by preexisting notions of cultural difference and expectations of how one would be perceived at the other locations. As Rabinowitz recalled:

The first broadcasts were the communities identifying themselves. Each café found it important to define their cultural identity through some kind of presentation or performance. They began to transmit images and icons and ideas that demonstrated the breadth and scope of their culture. They were very conscious of saying “This is who we are.” Blacks weren’t people who robbed liquor stores; they were poets.11

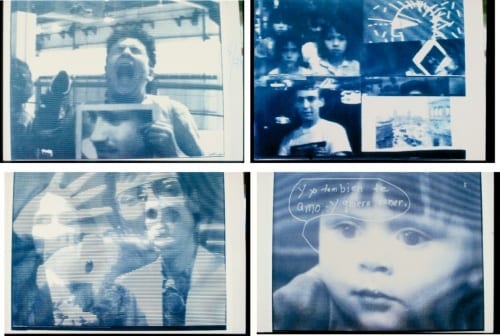

Users at Ana Maria transmitted music, poetry, and photographs of their community as well as historical images of Mexico, while gangs exchanged pictures of their signs and handshakes, collaging entire graffitied walls from image printouts. Once familiar with the technological arrangement and their place within it, users increasingly reprocessed transmissions, producing ever more complex communications. Original screenshots were repeatedly enriched—juxtaposed, superimposed, reassembled, drawn on, adorned with written commentaries—and then sent back out across the network. The slow-scan cameras, drawing tablets, and optical disk system allowed imagery to be shared among individuals who did not speak a common language. Real-time, digitally produced photo- and text-based montages became a primary language of exchange and collaboration across sites, encouraging users to scrutinize supposed similarities and differences as well as shared experiences. In one instance, white feminist poets at Günter’s in Venice Beach set up a virtual poetry slam, intended as an “overture” to black male poets at the Gumbo House in South LA.12 But the exchange remained one-sided, frustrating the Venice contingent’s expectations of amicable reciprocity: when the men read, the women responded, but the latter’s contributions elicited no reply. The feminist poets then confronted their counterparts, asking them to reflect on their behavior and the gender roles reinscribed by it. When the men tried to rationalize their response (or lack thereof), it set off a heated discussion. These participants engaged the telecommunication technology as a tool of struggle between contradictory points of view that would be resolved not because of the magic of the machines at hand, but because people could use them to actively negotiate conflict, recognize mutually restrictive categories of experience (in this case, overdetermined identity categories), and eventually find common ground and shared potentialities. In the end, the two groups met in person for a joint reading at Café Cultural, a poetry venue in East LA. As Galloway put it: “There was this whole idea about lack of encounter. LA is a bunch of cities looking for a place. . . . It’s about encounter; [Electronic Café] could support communities—that was the thing—communities not defined by geography.”13

Participants posted stories, proverbs, and their perspectives on topics ranging from the plight of South American refugees and culturally entrenched sexism and racism, poverty, and lack of education to schoolchildren wanting to find pen pals in other communities across Los Angeles. These posts often built on one another, transgressing boundaries, forging connections, and articulating common causes. Encountering a system of communication that was emphatically transparent, not necessarily in terms of its physical configuration but with respect to its ideological formation—its organizing categories, its parameters of knowledge and identity, and the kinds of relations it ultimately produced—users recognized and commented on its political potential. Some spoke of it as a more productive alternative to the frustrating state of mainstream television and radio. As one Community Memory post, titled “The Gilligan’s Island Syndrome,” explained, “the main limitation to communications technology is and always will be the content of the programming. Gilligan’s Island transmitted by direct-broadcast-satellite is still trash.”14 Indeed, it was clear to many that the forms of spectatorship that were rapidly emerging at this time—video playback, satellite, cable systems—may have offered more variety, but access to devices alone did not yield social progress. Another post summed up the situation:

I think the ELECTRONIC CAFE is a wonderful opportunity for the community(s) to define what we want of a communication system. . . . It is clear that the corporations already have this technology at their disposal. . . . It is now time for all of us to determine our own future by thinking PRACTICALLY about what kinds of uses and creations we can use it for. I like the idea that this is in cafes all over the city because at the very least that is what we all have in common.15

Pronouncements like these exemplify the way Electronic Café both facilitated a critique of techno-utopian visions and modeled a productive fantasy that eschewed fanciful hopes for harmonious resolution in favor of a concrete, open-ended process of reflexive interaction and exchange. The project was less successful when it reproduced conventional attitudes of emancipation—attitudes at least partially enabled by the artists’ hands-off approach—as a technical rather than political question. For some, the setup implied that social transformation would result from access alone, from “more complete participation in ‘community’ than otherwise might be possible,” as one user enthused. Another post proclaimed that new technologies would become “transformational media” when put into the hands of people broadcasting “messages and examples of LOVE, PEACE AND POSITIVE POSSIBILITIES FOR A HARMONIOUS WORLD.”16 In contrast, the transformative potential of Electronic Café emerged at those moments when it conveyed—and turned into a mobilizing impulse—the discrepancy between communication media’s means of production (material and intellectual) and the relations of users both to those means and to one another. Only then could participants recognize the limitations of technological protocols and begin to imagine and forge provisional connections that defied predetermined categories. The network became the technology of a popular struggle that demanded the negotiation of the ideal and the real, the ideological and the material, the dominant and the alternative—not as opposites, but as components of a relational field that was itself a subject of contention. Rather than propose new monolithic cultures of authenticity, Electronic Café modeled the construction of overlapping, polymorphous publics, all of which deviated from entrenched conventions of identity and experience. Future-imaginings were linked to an awareness of current conditions and their contexts. Participants could thus envision a future based on shared material circumstances and concerns and contrast such visions with pervasive myths of techno-social progress. Fantasy, in Negt and Kluge’s sense of the term—again, as the productive alignment of specific social needs and desires, critical consciousness, and the outside world—became the generator of truly innovative communication with a potential for real social transformation.

Techno-Economies

The politics of technology and fantasy that underlay Electronic Café had particular resonance at the time. Along with the humanist ideal of global unity on which every occurrence of the Olympics is built, LA’s games relied on a blend of innovation and corporatization that informed everything from the modernistic design of logos, typefaces, and uniforms to the widely publicized state-of-the-art telecommunication infrastructure and the opening ceremonies themselves, capped off by a man flying into the stadium on a jetpack to light the Olympic flame. Moreover, the late 1970s to the mid-1980s was a time of rapid technological development and enthusiastic public anticipation of a spectacular future generated by advances in computer equipment and telecommunication networks. Access to new machines promised fresh economic, social, and political possibilities, the supposed results of frictionless flows of information, decentralized authority, and deterritorialized relations. Whereas then-emergent computer and telecommunication technologies had originated in the mid-twentieth-century military-industrial complex, by the late 1960s and early 1970s the “communications revolution” was often linked to utopian dreams of freedom and innovation rooted in the countercultural moment.17 As Fred Turner has chronicled, the “New Communalists” of that period embraced technology as a social and emotional remedy: if industry and government made people “psychologically fragmented specialists, the technology-induced experience of togetherness would allow them to become both self-sufficient and whole once again.”18 By the mid-1980s these expansive hopes were firmly tied to new telecommunication technologies. As Gene Youngblood acknowledged at the time, such technologies promised to “invert the structure and function of mass media (a) from centralized output to decentralized input, (b) from hierarchy to heterarchy, (c) from mass audience to special audience, (d) from communication to conversation, (e) from commerce to community, (f) from nationstate to global village.”19

The personal computer, popularized in the early 1980s as an instrument of decentralization, democracy, and empowerment, was promoted as the embodiment of this vision.20 The emancipatory view of telecommunications was widely embraced as a way for everyone to participate in the making of the future—as an age-old science-fiction dream finally come true.21 As Turner argues, by the end of the 1980s, “the same machines that had served as the defining devices of cold war technocracy emerged as the symbols of transformation,” reconceived as a path to the “counterculture dream of empowered individualism, collaborative community, and spiritual communion.”22 The result was a fanciful “new economy” built on a mix of libertarian politics, techno-utopianism, and counterculture aesthetics.23 As the history of the Whole Earth network makes clear, hippie-era ideals were coopted by the emerging technological hub of Silicon Valley and the forces of capitalism. Countercultural entrepreneurs such as Stewart Brand championed the conventionally utopian techno-liberationist myths of the day.

Around this time a number of artists embraced the idea of advanced telecommunication technologies as emancipatory tools. Emerging satellite- and computer-networking capabilities were employed as a means to resist media consolidations and institutional constraints. Collectivism, collaboration, and a decentralization and deterritorialization of power structures would be achieved through direct individual use. Works such as Two-Way Demo: Send/Receive (1977), by Liza Bear, Willoughby Sharp, and Keith Sonnier, and Terminal Art (1980) by Roy Ascott grappled with the same techno-utopianism documented by Turner. These works were distinct from late 1960s and early 1970s endeavors such as Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) and the Art and Technology program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, both of which paired artists with tech-industry engineers and scientists in the hope of fueling mutual innovation. Many of the late 1970s and early 1980s telecommunication works presented novel devices as noncorporate and freely available (or soon to be), anticipating a time when such devices would be widely accessible and unhindered by dominant forces. New technology would mobilize and empower artists, allowing them to operate outside art institutions, wrest control over their tools, decentralize production, transcend geographic limitations, and unify their communities via new means of authentic individual and collective expression.

Underlying this vision was the belief that increased individualized access to devices and information would inevitably translate into greater democracy. The “free-flow doctrine,” promoted in the corporate and government discourse of the time, decoupled communication technologies from their problematic associations—military use, surveillance, commercialism, exploitation—and repoliticized them as limitless tools for personal expression, interaction, and emancipation.24 This doctrine mixed freedom of information and speech with free-market economics, rallying American popular opinion to support the privatization of the mass media and its capitalist expansion both domestically and internationally.

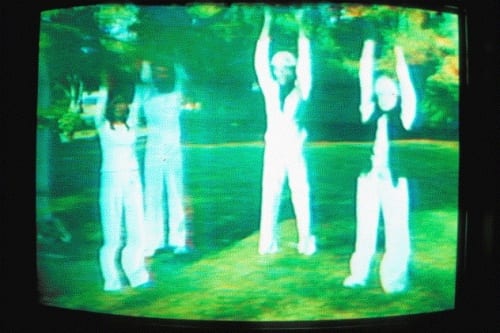

The early work of Mobile Image emerged out of this utopian zeitgeist and was initially limited to providing playful investigations of communicative interaction. The project Satellite Arts (The Image as Place) (1977) consisted of a set of improvisational dance collaborations performed by individuals in two locations, joined via bidirectional satellite uplink and set within sometimes composite, sometimes overlapping televisual space. The work provided a new site of encounter through mediated immediacy, a “third space” where performers interacted with each other, live-broadcast feeds, and the mechanical arrangement itself. This “image as place” did not construct a discrete virtual space but an architecture of complementary as well as competing material and immaterial sites of sensibilities and experience. Mobile Image used real-time satellite communication to establish an environment of multiple mediations of and as reality. Satellite Arts captured the imaginative and technological potential of new technologies to set up what the artists considered “alternative social worlds as laboratories for resocialization” as places for experimentation and retraining, for repurposing mass media “as technologies of the self”—as tools for finding new ways of extending the subject into the world and in relation to others.25

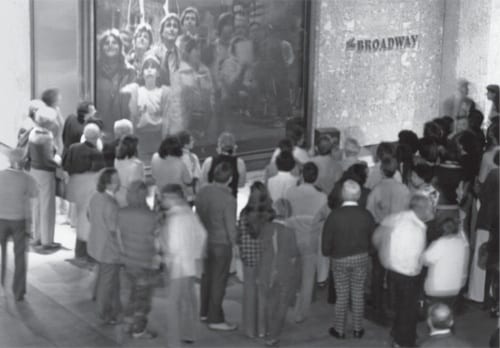

Mobile Image’s next ambitious project, Hole in Space (A Public Communication Sculpture) (1980), introduced technology deeper into everyday life. Two large screens were set up on the street—one in New York and the other in Los Angeles—and linked by live satellite feed. For two hours each day, over three successive evenings, people could see, hear, and interact with each other in real time from opposite sides of the country. The work aimed to offer a social experience that demonstrated what the artists called a “globally distributed electronic commons.”26 Unrehearsed and unscripted, without any overt involvement by the artists and technicians who operated it, the project’s direction—its form, etiquettes, and happenings at any given moment—developed on-site and through the social and situational dynamics of the crowd, activated by a sense of spontaneity and organic occurrence, while exposing existing expectations and patterns of behavior and social interaction. Mobile Image underscored the generally “public” aspect of technology, establishing a composite space involving both the material imbrication of distinct forms of publicity and the coexistence of multiple interactive and competing social and individual horizons of experience. With Hole in Space, they focused explicitly on the ways in which the urban context, the public, art, and technology interrelate as entangled sites of struggle.

With Electronic Café, Mobile Image developed and expanded this approach. It embraced new tools while setting in critical relief typical utopian prophecies of an idealized, electronically networked public or free-flowing individualized expression, as well as underlining corporate-driven promises divorced from, or designed to obfuscate, power structures and broad political and ideological realities. It was a model of contentious relationality defined by the conscious transgression of existing geographic, racial, cultural, and technological demarcations through expanded communicative processes. It compelled users to confront their own roles within existing power structures, enlisting them as producers, receivers, and manipulators of content.

Thus Electronic Café belongs not only to the history of techno-activism, but also to the legacy of post-Minimalist aesthetics, particularly Conceptual art, which was at least partially defined by an increased emphasis on what Alexander Alberro describes as “the possibilities of publicness and distribution.”27 When artists and critics of the late 1960s sought the dematerialization of the art object, it was not solely to overcome the restrictive commodification imposed by aestheticized, physical form. It was also to enable and demand participation, an opening up of art that, as Lucy Lippard and John Chandler put it in 1967, offers a “curious kind of Utopianism” whose “tabula rasa” would provoke a thinking-through of ideas determined by the artwork as a catalyst or device wielded by those experiencing it.28 According to Sol LeWitt, the idea “becomes the machine that makes the art,” conjuring a technological metaphor that posits the viewer as an integral, ideally active part of the imaginative process.29 And because, in this conceptualist schema, ideas are always shared and meaning is created in that process, aesthetic production is ostensibly depersonalized, and therefore accessible, participatory, and public, upending hierarchical notions of skill and authorship in favor of communicative action. According to Benjamin Buchloh, however, this apparent democratization of means ultimately turned into a de facto “structural relationship of absolute equivalents” in which the quantity of information exchanged supplanted the potentially critical quality of aesthetic experience. Consequently, Buchloh argues, Conceptualist works often replicated rather than transgressed the late capitalist “logic of administration,” thus reinforcing the institutions in which art serves as a mechanism for merely symbolic liberation, in which “artistic production is transformed into a tool of ideological control and cultural legitimation.”30 Coming in the wake of Conceptualism, Electronic Café \can be understood as having heeded but not succumbed to Buchloh’s critique.

The work thus relates to several Postconceptualist practices of the 1970s that built on the earlier movement but challenged some of its core tenets. In particular, Electronic Café resembles what Alberro calls an “antithetical model,” exemplified by artists such as Martha Rosler, Fred Lonidier, Allan Sekula, and Phel Steinmetz, who with their activist, photo- and text-heavy practices set out to show that “self-determination and communication, even in advanced forms of capitalist control, is still a historical option and artistic possibility.”31 What distinguishes their work from that of other, more pessimistic Postconceptualists is that it not only critiques systems of representation for their ideological foundations but reasserts the possibility to politically intervene within existing institutions. It refuses to cede the emancipatory potential of communication in the contemporary public sphere.32 Electronic Café likewise problematized the presumed neutrality of various technologies of representation—linguistic, visual, technical, and otherwise—in order to elicit a conscious refunctioning of productive and distributive tools.

At first glance, Electronic Café might seem to be a precursor of the kinds of participatory, technologically oriented art ventures that emerged over the ensuing decade, including dial-up bulletin board system (BBS) artist networks such as THE THING (1991) and what is commonly termed relational aesthetics, a group of primarily “offline” practices that nonetheless adopted various networking paradigms of the moment—participation, communication, collectivity, sociality. Yet Mobile Image pointedly eschewed the utopian undertones of such movements, which arguably succumbed to the same late capitalist “logic of administration” that Buchloh critiques.

Closer to what Claire Bishop terms “relational antagonism,”33 Electronic Café combined the dematerialization and deterritorialization enabled by the electronic form with the specific ethnic, racial, and class struggles mapped onto the highly territorial geography of a largely segregated city. Mobile Image deliberately selected neighborhoods that not only were physically and culturally separate, but also experienced persistent tensions between them that were aired and debated on the network. For example, the African American and Korean American communities were, Galloway explains, “at each other’s throats” over perceptions of economic exploitation.34 This type of site-specificity tied the technological apparatus to the complex histories of the local communities involved and to their relationships to each other, to power, and to a range of competing past, present, and future imaginaries. Electronic Café offered participants a glimpse of a counter-technological order in which users could not only broadcast their personal expressions but also partake in relational negotiations.

Alongside personal stories and calls for peaceful coexistence, exchanges about electoral politics, activism, religion, pornography, sexism, and other topics proliferated on the Community Memory bulletin board. “The person that entered the ‘Nobody for President’ obviously is very cynical and without hope,” read one post. “I would like to enter into dialogue with him/her.” “Why is it that no one admits they are a sexist?” asked another, to which someone responded, “Because they are not sure of their gender.” At one point a participant transmitted pictures and a narrative of himself being beaten by police, triggering a discussion about police brutality against African Americans in Los Angeles. Even as new bonds were forming, additional conflicts were emerging, such as the exchange between the feminist and black poets mentioned earlier. These “antagonistic” interactions did not enable a vision of a communalist utopia of frictionless communication but one of critical and productive fantasy as a subversive, mobilizing process for challenging present ideological and material arrangements.

Critical Utopia and Counterpublicity

Mobile Image’s attempt to model a form of productive future-imagining corresponded with a particular discursive shift in America. Alongside the techno-euphoria of the early to mid-1980s, writings on science fiction and the politics of utopia proliferated. Though diverse in subject matter, many of these texts were attempts to trace the historical development and contemporary pertinence of (and indeed, the urgent need for) future imagining. They struggled to articulate a truly progressive, innovative engagement with the future that would transform rather than merely repackage the ideological and material limitations of the past and the present.35

They also distinguished such an engagement from early modern conceptions of utopia, which were explicitly linked to the rise of capitalism and its ideological structure. According to Fredric Jameson, that structure perpetuated a notion of “progress” that validated enduring discrepancies between everyday experiences and the promises of tomorrow. As Tom Moylan explains, early utopian fictions of the future “provided images of alternatives to the given situation which, while not yet existing in history, drew on the contradictions of the time and anticipated a response to the conflicting needs of the dominant and subordinate classes.”36 Deeply embedded in the colonial and imperial ethos, these “alternatives” were first projected onto the uncharted geographical spaces of the New World, then later relocated to another time—to the future, when truly revolutionary change would ostensibly yield a perfected society. However, as part of a class struggle over the means of material and cultural creative production and exploitation, such utopian visions have the power to both symbolically appease and politically challenge: “Utopian dissatisfaction and imagery has been enlisted into the process of the creation of needs subordinated to the demands of production and profit; while, on the other hand, the very dream-making activity of the utopian imagination continually resists the limitation of human desire to the economic and bureaucratic demands of the given system.”37 As Robert Elliot Fox discussed with regard to Samuel R. Delany’s mid-1970s novels, this “dichotomy of experience” of both gratification and alienation accounts for the resurgence of utopian desires in a specifically American context. The political upheaval of the 1960s and its aftermath produced a creative activism, particularly among feminist and African American writers and artists, that sought to raise consciousness about and transcend the commercial-industrial machine of the utopian dreamscape as an engine for the sale of material and immaterial consumer goods, from advertisements for suburban lifestyles to Hollywood values and Disneyworld ideals.38

Crucially, this surge in subversive utopianism was self-consciously critical, acknowledging the dialectical nature of utopia, its historical failures as well as its transgressive potential. What Moylan terms “critical utopia” revives future imagining but refuses predetermined solutions and resolutions, dwelling instead on the conflicts between present and prospective conditions;39 it “rejects utopia as blueprint while preserving it as dream.”40 For example, Delany’s sci-fi narratives articulate what Jane B. Weedman calls the conflict between “the prevailing idealism of the American dream and Black American reality”; they manifest a “double consciousness” in W. E. B. Du Bois’s sense of the term, Weedman explains, “a psychological dichotomy which results when an individual lives in a culture, such as the black community, yet must be aware for his survival of the workings and expectations of a dominate [sic] culture.”41 Rather than paint a beautiful picture of the future that only distracts from the often violent constraints of the given, a critical utopian practice has as its subject the construction of utopia, not as an inherently human need but as a systemic necessity. Looking to the future is thus understood as a highly contested anticipation of the not-yet-concrete that determines the relationality between past, present, and future experiences and perspectives, who and what gets to be part of the future imaginary, and whose histories will determine the outcome of what tomorrow looks like.

Broadly defined, the public sphere is made up of the instruments and spaces that organize such experiences and perspectives. These tools and sites of communication and knowledge production include technical devices such as computers and televisions as well as materials and institutions, from books and art objects to schools, churches, and sports events. Together these determine what Negt and Kluge call “the social horizon of experience.”42 Any critical-transgressive activism must consider the means of production in this expanded sense, as a struggle over the tools that dictate the future imaginary. Because such arrangements of collective experience are subject to power systems, and to determined notions and rituals of subjectivity, community, identity, and history being amplified or repressed, they are inevitably bound to apparatuses of publicity—to the mechanisms by which people both transmit and receive information, attitudes, and desires. In this sense, “technologies” constitute the public sphere. Thus a critical utopian practice has to address pervasive myths of technological progressivism.

Galloway and Rabinowitz met in Paris in the mid-1970s, each working on expanding the City of Light’s perpetual modernity through various electronic-communicative projects. There they also met the French philosopher Félix Guattari, who was himself deeply invested in tele-connective activism. All three shared an interest in social change and technology and were skeptical that the promise of telecommunicative connectivity would lead to material and intellectual emancipation. According to Guattari, revolution came not simply through more communication—“They talk, oh yes indeed, they talk all the time”—but through a specific type of communication, one that destroys “the domination of isolation.”43 Such communication would connect the fragmented communities of the dominated in their desire to overcome alienation and to create an image not of a future society, but of “a collective competence” through “collective action.”44

According to Mobile Image, Electronic Café was consciously modeled on a particular idea of the French coffeehouse as a site of critical public debate and a cradle of revolutionary action. However, their new high-tech version went beyond traditional accounts of the café’s role as part of the generation and transformation of the bourgeois public sphere, the ideal arena of an inclusive, autonomous critical exchange. Deeply immersed at the time in the context of and discussion surrounding communication and power, they recognized that a simple reproduction of then-current communication structures based on a traditional notion of bourgeois publicity—predicated on what Miriam Hansen calls “formal conditions of communication (free association, equal participation, deliberation, polite argument)”—would not suffice.45 Echoing contemporaneous sci-fi and utopia debates, writers and theorists such as Negt and Kluge, Guattari, Herbert Schiller, and Gene Youngblood cast a critical eye on myths of the democratization of culture through technological access and innovation. Schiller and Youngblood had close ties to the California art and technology scene of those years: Schiller was a professor of communication at the University of California, San Diego, and Youngblood was a Los Angeles–based critic and professor at the California Institute of the Arts who would become a close collaborator of Mobile Image. Both theorists took part in Televiews, a 1981 video-relay project at UCSD led by the artist Ulysses Jenkins. This project was closely monitored by Rabinowitz and Galloway, who later invited Jenkins to play a pivotal role in the Electronic Café as an artist-in-residence at the Gumbo House location.

In a lecture as part of Televiews, Schiller warned of overly enthusiastic technological forecasts couched in terms of undifferentiated public access and ideals of liberation through technological innovation that promises flexibility, creativity, and control. In his 1976 book Communication and Cultural Domination, he had explicitly referred to mass media as “public” media, addressing the ideological dimension of how information is produced and disseminated.46 If technology is perceived as just a set of devices—hence, as politically and ideologically neutral—it merely serves to relay the same messages produced elsewhere in society. New technology, Schiller explains, does not automatically produce a new society:

Technology, which appears mainly, and is almost exclusively understood, as visible machinery and hardware, lends itself admirably to the claim that it is neutral, value free, and employable under any social order, for sometimes quite different ends. Moreover, the concept of free flow of information, which holds that benefits accrue to everyone participating in that flow, but which, in reality, is a one-way street for exercising domination by the already-powerful, is extended to technology—with the still greater likelihood of intensifying the dependency of the weaker parties.47

Like Televiews, Electronic Café aimed to reveal this dimension of the political utility of communication devices—the fact that, as Schiller put it, “technology is a social construct.”48 Its futurist consoles pointedly alluded to the facade of commercial techno-progressivism, while each also incorporated a live television feed—including news, entertainment, live events from the Olympic Games, and coverage of that year’s presidential campaign—whose imagery could be combined, juxtaposed, written on, and otherwise reprocessed and rebroadcast across the network. Users of the drawing tablets, slow-scan cameras, and other devices thus saw their own creations and manipulations continuously juxtaposed with those of a seemingly omnipotent media industry. Such an encounter with the mechanisms of information production and dissemination is crucial to fighting what Youngblood refers to as “the cultural imperialism of the mass media.”49 Users became producers, appropriating, transforming, and relaying the information and material they received, but the quality of their transmissions contrasted with prevailing modes of distribution, based on conventional notions of a monolithic, all-encompassing sphere of idealized public exchange.

What was so distinct about Electronic Café was not that it permitted people to utilize mass media and telecommunication technologies to send their own personal commentaries into some preset apparatus or abstract, uniform ether. It was not simply a matter of access to broadcasting devices and channels, of participation in “free-flow.” Rather, the nature of the communications was emphatically particularized, directed, and localized, enacted between various interdependent publics from specific café locations and according to continuously negotiated concerns that transcended predetermined categories of identity and experience. As the project made clear to users, the notion of a singular public was replaced by that of multifarious publics that were relational, specific, contested, and grounded in myriad overlapping sociopolitical contexts.

Electronic Café engaged, at least in part, the same cultural and communicative crisis articulated in contemporaneous theories of postmodernism, particularly those that focused on an increasingly technologized world. Along with Jameson, late 1970s and early 1980s writers such as Jean Baudrillard and Jean-François Lyotard characterized post-1960s society as one dominated by computerization, electronic information, media spectacle, and multinational capitalism, resulting in a dissolution of subjectivity and authentic expression and the disappearance of a productive public sphere. To Baudrillard, the pandemic spread of advanced communication networks had ushered in a narcissistic era, in which consumers exist in isolation. The domestic space had become “a living satellite,” a thoroughly privatized space where users merely send and receive signals, “a pure screen, a switching center for all the networks of influence.”50 Hence, he explains,

This electronic “encephalization” and miniaturization of circuits and energy, this transistorization of the environment, relegates to total uselessness, desuetude and almost obscenity all that used to fill our lives. . . . As soon as behavior is crystallized on certain screens and operational terminals, what’s left appears only as a large useless body, deserted and condemned. The real itself appears as a large useless body.51

Whereas alienation once motivated opposition and resistance, all is now subsumed, in Baudrillard’s mournful view, by an illusory freedom via a “pornography of information,” abundant, fluid, and free-flowing.

Somewhat less bleak, the critiques by Lyotard and Jameson offer similar assessments but with at least some potential for certain kinds of agency. To Lyotard, “computerized society” is marked by a disintegration of grand narratives, with no possibility for either universal consensus or the establishment of a “pure” alternative to the current system. This “postmodern condition” emerges alongside an increasing concentration of power in the hands of those who control information, and thus the economic system and knowledge production itself. In response, Lyotard calls for a “quite simple” solution to the problem of computerization: free public access to memory and data banks, which would enable a multiplicity of open discussions and self-conscious moments of consensus informed by inexhaustible reserves of information.52 Jameson speaks specifically to the “aesthetic dilemma” facing the postmodern artist: in a technologized society drained of authenticity and subjectivity, it is no longer clear what the function of art is.53 Mass culture responds with pastiche, epitomized by the science-fiction movie Star Wars (1977), with its appropriation of bygone forms in nostalgic revival of a prior generation’s future-imaginings. The only viable option for “high art,” according to Jameson, is for practitioners to speak through “dead styles,” rendering art a rumination on itself.54 Indeed, so much art of the period was understood in those very terms.

Mobile Image concurred with some of these core diagnoses—the saturation of society by prepackaged broadcast content, the excessive privatization of communication, the persistence of myths of technological progress and illusions of freedom, and the resulting threat to an operational public sphere. But they rejected the nihilism epitomized by Baudrillard’s theory, even as they openly rebutted industry-peddled promises of surefire social progress. To them, telecommunication networks were neither inherently democratizing nor part of a totalizing spectacle of control that leaves the user helpless to intervene.

Yet, crucially, Electronic Café represented an approach that was also distinct from the constructive options presented by theorists like Jameson and Lyotard. Along with his call for increased access, the latter saw works of art as symbolic of budding sensibilities and thus capable of eliciting philosophical reflection on a computerized age. In 1985 Lyotard cocurated Les Immatériaux, a landmark multimedia exhibition at the Centre Pompidou meant to highlight the bewildering and destabilizing effects of emergent technologies, or as he put it, the “incertitude about the identity of the human individual in his condition of such improbable immateriality.”55 Focusing on conventional mediums such as painting and film, Jameson abided by a similar conception of cultural production as symbol, whether a pastiche that encapsulates the postmodern or a reflexive re-presentation of the inauthenticity of artistic expression itself. For both thinkers, the artist is fundamentally a producer of images—material or immaterial—that embody current conditions and potentially provoke contemplation.

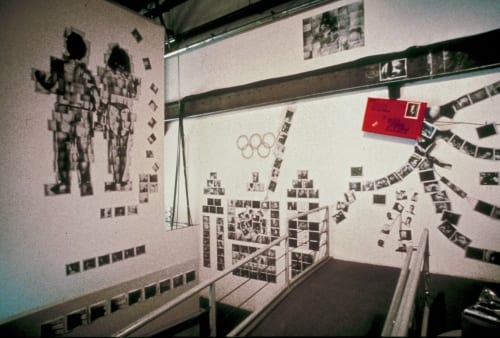

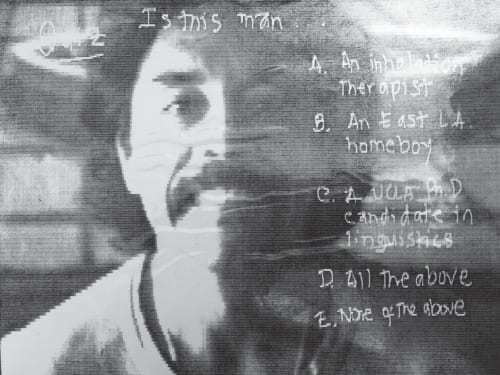

Electronic Café offered a very different mode of artistic production: a participatory and open-ended social labor that both raised consciousness about the politics of technology and modeled ways to use it to effect social transformation. Along with digitally archiving their scans, drawings, and manipulated pictures, users printed and hung them on the walls of their “home” sites. They also transmitted some to the Museum of Contemporary Art—the project’s pointedly institutional arm—where they were printed out and pinned to a mezzanine wall. The resulting collages of impressions and expressions, memories and imaginaries, emphatically juxtaposed the various self-assumed, socially ascribed, and culturally specific publics with one another and with an official public institution of ostensible collective relevance. It also foregrounded the constructedness of subjectivity itself. After sending images via the electronic network, users would visit the museum in person to experience and partake in the arrangement and rearrangement of materials. This accumulation combined, for example, a TV-screen grab of Ronald Reagan scratching his head over the caption “Health, Housing, Education”; documentation of a visiting African dignitary at the Gumbo House; and a General Motors advertisement that read “Nobody sweats the details like GM.” Another cluster juxtaposed a magazine cover featuring the story of an East LA “assault with a deadly weapon” with a series of Mexican vintage postcards and an Electronic Café–produced headshot of a man, prompting its viewers to answer the following multiple-choice quiz: “Is this man . . . A. An inhalation therapist; B. An East L.A. homeboy; C. A UCLA Ph.D. candidate in linguistics; D. All the above; E. None of the above.”

Electronic Café engaged crucial questions of public life in the digital age. It not only encouraged users to envision alternate arrangements of media control but enabled transgressive forms of public exchange—what Negt and Kluge call counterpublicity. As they explain, dominant publicity actively marginalizes nondominant groups by excluding them from its legitimizing power, which determines what can be said and how, and whose experiences are considered relevant.56 A successful counterpublicity needs to productively work beyond the reproductive ideological mechanisms of inclusion-exclusion. Set against the conformism of technological consumption and the myth of inherently rebellious forms of collaboration through creative heterogeneity, Electronic Café brought users together specifically so that they could recognize the ways in which normative participation in the “freedoms” offered by current telecommunication practices actually facilitated their own marginalization. Mobile Image modeled a form of counterpublicity designed to upend this arrangement and the power sustained by it.

As a form of counterpublicity, Electronic Café facilitated instances of solidarity and reciprocity grounded in collective experiences of marginalization and exclusion. Yet due to the its particular setup—its mix of futuristic design and available technologies, commercial broadcast chatter and ad hoc creativity, uncharted electronic networks and familiar locales, prescribed cultural differences and experiences of common social concerns, myths of universal humanism and unexpected, historically specific needs—these instances were also highly reflexive. Participants were made aware of the mediated nature of their exchanges, of the fact that their communication was no longer rooted in traditional forms of social interaction and face-to-face relations, and that such exchanges were therefore subject to heightened evaluation, conflict, and negotiation.

Electronic Café was above all an act of relating. It did not offer a blueprint for a better tomorrow kept at arm’s length, the proverbial carrot in front of the cart, but a self-conscious, politicized fantasy via concrete acts of counterpublicity. Electronic Café provides a crucial contribution to contemporary discourse, nuancing categories of artistic practice that are too often lumped together as “new media” or “socially engaged art” while also engaging broader political and ideological struggles facing us in today’s world of instant digital interaction, social media, and consolidated corporate control.

Philip Glahn is associate professor of critical studies and aesthetics at Tyler School of Art and Architecture, Temple University, Philadelphia. Cary Levine is associate professor of contemporary art history at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. The current article is part of a larger book project on the work of Mobile Image and the intersections of art, politics, and communication technologies.

- The authors would like to thank the following people for their help with this article: Kit Galloway, Ana Coria, Ben Caldwell, Ulysses Jenkins, Hye-Sook Park, Daniel Martinez, Jose Luis Sedano, Gene Youngblood, John J. Curley, Richard Langston, and Nell McClister. Some of the ideas in this article were presented in a paper for the 2016 CAA Annual Conference (in the session “Art and Invention in the US”), subsequently published in Panorama 1, no. 3 (June 2016). ↩

- Bertolt Brecht, “The Radio as an Apparatus of Communication” (1932), in Brecht on Theatre, ed. and trans. John Willett (New York: Hill and Wang, 1964), 53. ↩

- Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge, “The Public Sphere and Experience: Selections,” trans. Peter Labanyi, October 46 (Fall 1988): 76. Emphasis added. ↩

- Ibid., 79. ↩

- Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee, Richard B. Perelman, ed., Official Report of the Games of the XXIII Olympiad, Los Angeles, 1984, vol 1, Organization and Planning (1985), 528. ↩

- Jose Luis Sedano, interview with the authors, Los Angeles, March 3, 2016. ↩

- Hye-Sook Park, interview with the authors, Los Angeles, March 2, 2016. ↩

- Günter Hiller, quoted in Kenneth Fanucchi, “Café Owner Shuts Doors, Stays Hopeful,”

Los Angeles Times, April 11, 1985, http://articles.latimes.com/1985-04-11/news

/we-12013_1_cafe-owner. ↩ - Sherrie Rabinowitz, quoted in D. Snowden, “Mobile Image Works on a Global Vision,” Los Angeles Times, October 19, 1987, http://search

.proquest.com/docview/811000832?accountid=14244. ↩ - The Community Memory Project: An Introduction (1982), informational booklet, the Sherrie Rabinowitz and Kit Galloway Archive, Piñon Hills, CA. ↩

- Sherrie Rabinowitz, unpublished interview, the Sherrie Rabinowitz and Kit Galloway Archive, Piñon Hills, CA. ↩

- Kit Galloway, interview with the authors, Piñon Hills, CA, March 4, 2016. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Anonymous user, Electronic Café Community Memory record, the Sherrie Rabinowitz and Kit Galloway Archive, Piñon Hills, CA. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1996), 5. ↩

- Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 4. ↩

- Gene Youngblood, “Metadesign: Toward a Postmodernism of Reconstruction,” Ars Electronica, 1986, n.p. ↩

- Ted Friedman, Electric Dreams: Computers in American Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 99. ↩

- Ibid., 100–101. ↩

- Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture, 2, 32. ↩

- Ibid., 208–9. ↩

- Herbert Schiller, Communication and Cultural Domination (White Plains, NY: International Arts and Sciences Press, 1976), 24–25. ↩

- Galloway and Rabinowitz, quoted in Gene Youngblood, unpublished draft of manuscript, 27, the Sherrie Rabinowitz and Kit Galloway Archive. ↩

- Quoted in Annemarie Chandler, “Animating the Social: Mobile Image/Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz,” in At a Distance: Precursors to Art and Activism on the Internet, ed. Chandler and Norie Neumark (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 164. ↩

- Alexander Alberro, “Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977,” in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Alberro and Blake Stimson (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000), xvii. ↩

- Lucy Lippard and John Chandler, “The Dematerialization of Art” (1968), reprinted in Alberro and Stimson, Conceptual Art, 47–48. ↩

- Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” (1967), reprinted in Alberro and Stimson, 12. ↩

- Benjamin Buchloh, “Conceptual Art, 1962–1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions” (1989), reprinted in Alberro and Stimson, 530–33. ↩

- Alberro, “Reconsidering Conceptual Art,” xxix. ↩

- Ibid., xxx. ↩

- Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October 110 (Fall 2004), 53–80. ↩

- Galloway, interview with the authors, Piñon Hills, CA, May 6, 2015. ↩

- Tom Moylan, Demand the Impossible: Science Fiction and the Utopian Imagination (Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang, 2014), 1. ↩

- Ibid., 3. ↩

- Ibid., 4. ↩

- Robert Elliot Fox, “The Politics of Desire in Delany’s Triton and The Tides of Lust,” Black American Literature Forum 18, no. 2 (Summer 1984): 52. ↩

- Moylan, 10. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Cited in Mary Kay Bray, “Rituals of Reversal: Double Consciousness in Delaney’s Dhalgren,” Black American Literature Forum 18, no. 2 (Summer 1984): 57. ↩

- Negt and Kluge, 63. ↩

- Félix Guattari, Molecular Revolution: Psychiatry and Politics (1977), trans. Rosemary Sheet (Middlesex, UK, and New York: Penguin Books, 1984), 236. ↩

- Ibid., 241. ↩

- Miriam Hansen, “Unstable Mixtures, Dilated Spheres: Negt and Kluge’s The Public Sphere and Experience, Twenty Years later,” in Public Culture 5, no. 2 (Winter 1993), 201. ↩

- Schiller, Communication and Cultural Domination. ↩

- Ibid., 49-50. ↩

- Ibid., 89. ↩

- Youngblood, “Metadesign,” n.p. ↩

- Jean Baudrillard, “Ecstasy of Communication,” trans. John Johnston, in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Seattle: Bay Press, 1983), 127–33. ↩

- Ibid., 129. ↩

- Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), 66–67. ↩

- Fredric Jameson, “Postmodernism and Consumer Society,” in Foster, The Anti-Aesthetic, 115. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- See Bernard Blistène, “Les Immatériaux: A Conversation with Jean-François Lyotard,” Flash Art 121 (March 1985): 32–39; reprinted in Rearview, May 27, 2014, http://www.art-agenda.com/reviews/les-immateriaux-a-conversation-with-jean-francois-lyotard-and-bernard-blistene/. ↩

- Negt and Kluge, 72. ↩