From Art Journal 78, no. 4 (Winter 2019)

What I wanted to do was to come up with a piece of music that I loved intensely, that was completely personal, exactly what I wanted in every detail, but that was arrived at by impersonal means.1

—Steve Reich, 1972

In 1966, the musician Steve Reich (b. 1936) made a sound composition titled Come Out.2 It begins with the voice of a man: “I had to, like, open the bruise up and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them.” This sentence repeats two more times, followed by the fragment, “come out to show them,” over the course of nearly thirteen minutes until speech becomes music through rhythm alone. Reich looped the sample on two channels that start in unison and gradually slip out of sync so that the full phrase, “come out to show them,” holds together for only a few minutes. In an effect called phase shifting, the two channels continue to move out of sync, and the tail end of the phrase, “show them,” slips behind the staccato repetition of “come out to—come out to—come out to” with a rhythmic intensity. Reich then split the audio, dividing two channels into four, creating a round, or canon, and then into eight, developing an environment of sound that is nearly indistinguishable from the original phrase.3

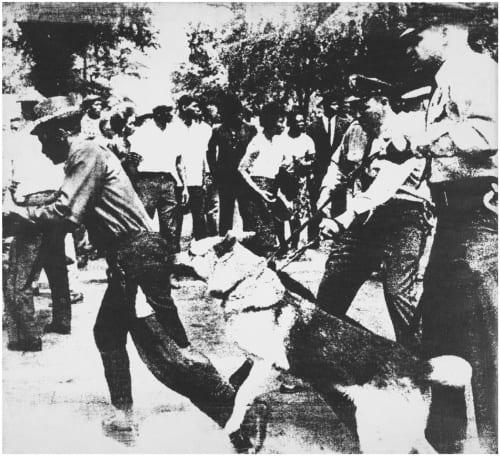

The voice that dissolves in Come Out belongs to Daniel Hamm. When a toppled fruit stand in Harlem became a site of Puerto Rican and African American children’s mischievous play in April 1964, the riot police who regularly patrolled the area arrived at the scene. Hamm and several other young African American men who intervened to protect the children against the threat of excessive force were detained overnight and severely beaten by police.4 Because Hamm was bruised, though not bleeding, officers deemed him ineligible for medical treatment. And because vocalizing his pain was ineffective, he forced material proof from his body: “I had to, like, open the bruise up and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them.”

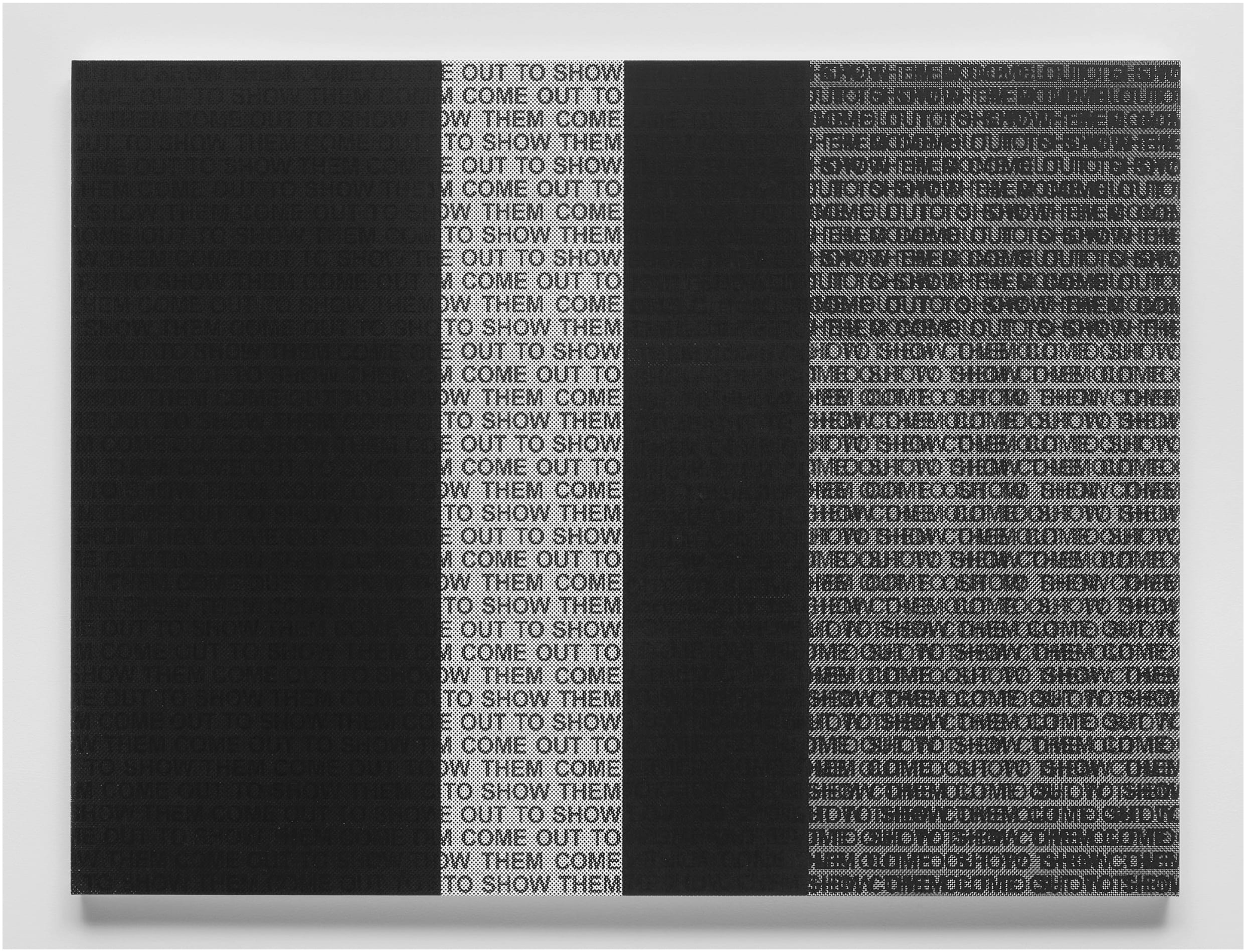

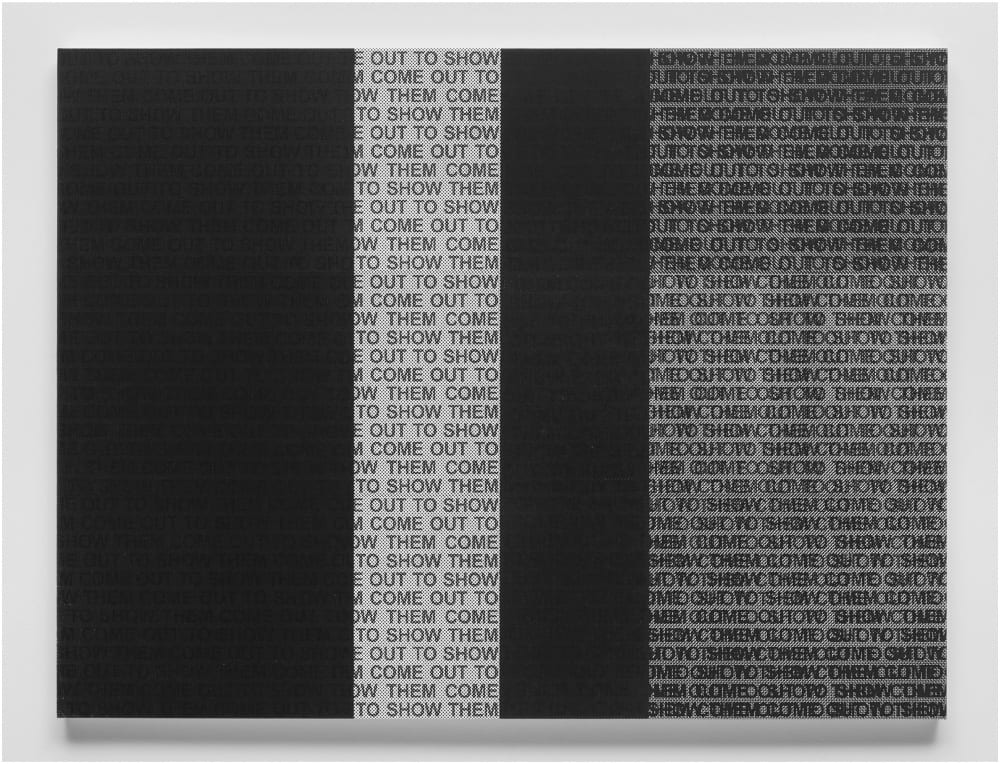

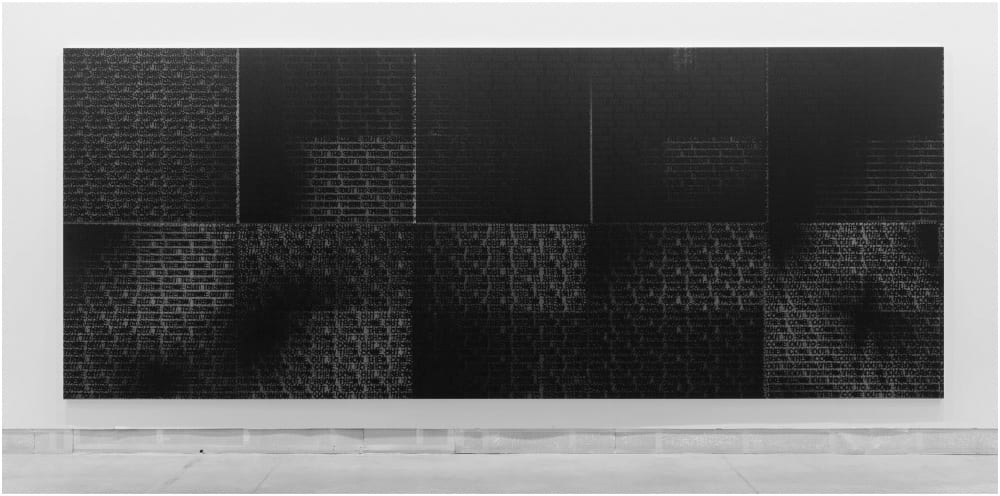

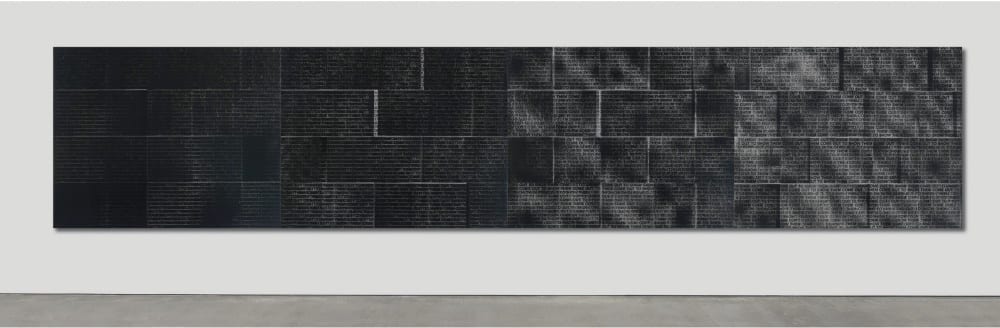

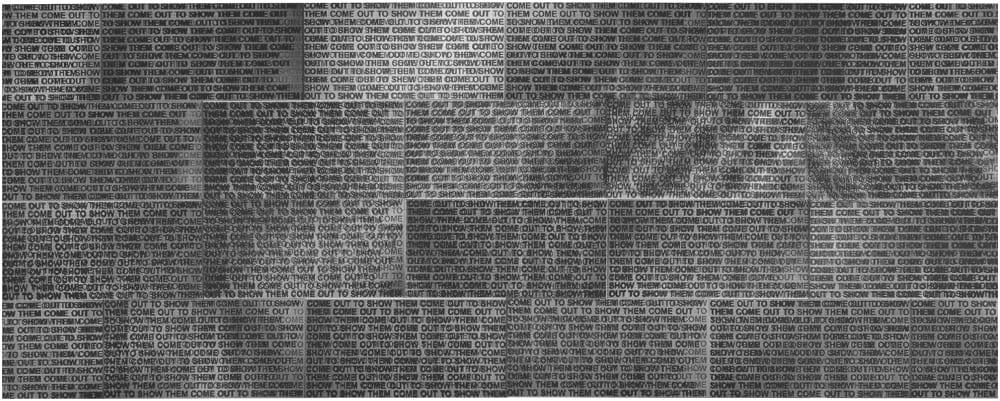

In 2014 the artist Glenn Ligon (b. 1960) hosted a class visit to his studio and was asked about what music was playing; it was Come Out. As a committed formalist, Ligon was familiar with Reich’s music and saw in him a kindred spirit whose embrace of repetition as a technique of abstraction mirrored his own. It was not until that visit, however, freshly immersed in a news cycle of antiblack violence, that he observed in Come Out an uncanny conceptual resonance with both his practice and the present.5 This essay explores the ensuing body of work that Ligon produced in the next two years: large black-and-white silkscreen paintings filled edge to edge with the phrase “come out to show them” in tightly arranged lines of sans serif type in all capital letters. In sixteen monumental paintings and twenty-one studies in total, each numerically titled Come Out, Ligon expressively renders the unspeakable abstraction of racial violence, channeled ambivalently through Reich’s systematic structures of reproduction.6

(artwork © Glenn Ligon; photograph provided by the artist, Hauser & Wirth, New York, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, and Chantal Crousel, Paris)

This essay explores how and why Ligon’s paintings visually echo Reich’s sound composition, extending the various transformations and remediations of Hamm’s speech (recorded, split, spliced, looped, painted, and overprinted) from the sonic into the visual realm. More importantly, they surface the ambivalent violence of Reich’s composition: how it obscures the content of speech through its relentless repetition, how the ensuing abstraction of Hamm’s words, though rhythmically interesting, seems to collapse both his subjectivity and his voice into noise. “Come out to show them” is a sonic trace of corporeal trauma and as such brings with it some amount of pain. To what ends, then, does Ligon visualize and thus revive the pains of the past fifty years later?

Incorporating both the composition and the listening experience of Come Out into the space of painting, Ligon considers the paradoxical coexistence of the song’s structural and affective qualities, and acknowledges Hamm’s speech as a synecdoche for other embodied struggles within the civil rights movement. I join other scholars in acknowledging the strangeness of Come Out; although Reich described it as a civil rights piece, further analysis reflects his political and racial ambivalence.7 I center ambivalence as a protocol for reading Reich’s appropriation of Hamm’s voice and as a generative concept in Ligon’s work. Ambivalence is defined as a state of irreconcilable or contradictory desires, joining other destabilizing strategies in Ligon’s practice that fuel the difficulty of his works and their resistance to interpretation.

Ligon is primarily known for paintings that appropriate and manipulate text from literary sources to speak to the vicissitudes of black life in the United States through systems of repetition and obfuscation. His earliest text paintings from the late 1980s and early 1990s deploy these methods in the service of gestural expression. Ligon uses a stencil and oilstick to repeat an appropriated phrase, and language loses legibility with the accrual of paint as the artist moves the stencil down the surface of the canvas. As the viewer reads from left to right and top to bottom, letters become marks in a process of narrative failure until they illegibly materialize only as dense impasto at the painting’s bottom edge. This gravitational pull of textural accrual is absent in the Come Out paintings. They maintain a slick, mechanical-looking appearance, replacing surface texture with smooth opacity. In the physical pressure used to push etcher’s ink—thick and resistant—through the matrix, Ligon’s labor is not lost; it is simply not visible. The silkscreen’s placement and displacement pulls text apart, creating dizzying moiré patterns and pulsating surfaces that channel the harmonic rhythms of Reich’s composition, particularly the stuttering effect of auditory phase shift.8 Some canvases bear hard-edged vertical bands of distinctly blackened ground. In these darkest, blackest areas of the canvas, where it would appear we can read nothing, the text is in fact most legible, owing to the subtle contrast between the background ink and the slightly more matte foreground ink, as in the nearly all black Come Out #10. In others, the text’s superimposition creates the illusion of double vision, producing hazy, monochromatic grids that appear as large fields of blurred and mottled blacks. Even the act of description reveals the excess materiality of language that registers what remains beyond the work itself, or what Fred Moten would term “its irreducibly present madness.”9

Speech Transformation

Daniel Hamm’s presence at the fruit stand in the spring of 1964 put him on the radar of local police, and he was among another group of young African American men known as the Harlem Six, who, just weeks later, were falsely accused of murdering a white Jewish shopkeeper in Harlem.10 Though their guilt was never proved, all pled guilty, their initial confessions forced under physical duress and amid doubt over the possibility of a fair trial. The group’s collective endurance of physical suffering and judicial bias attracted the attention of major public figures, including James Baldwin, and fueled local protests against New York City’s intensified policing. The case is inextricable from the Harlem Riots and similar uprisings that shook the country in 1964 and 1965, symbolic of the challenges faced by civil rights activists to transform the bulwark of state power and social prejudice that continues to fuel a climate of antiblack violence today.

Baldwin reflected on the situation in the Nation: “The citizens of Harlem, who, as we have seen, can come to grief at any hour in the streets, and who are not safe at their windows, are forbidden the very air.”11 The incident exposed several strains of anxiety at the time: the hardening associations between youth criminality and race, the perceived threat of public gatherings of people of color, and the rise of the carceral state in New York City.12 Just a few months before Hamm’s arrest, the New York state legislature passed two new anticrime statutes, “stop and frisk” and “no knock,” that predominantly targeted people of color. When Baldwin wrote that the people of Harlem were forbidden the very air, he referred to the fact that police regularly shot at buildings, often striking innocent civilians whom they feared were armed.

Frustrated with the state-appointed legal counsel for the Harlem Six, activists mobilized to raise funds for a retrial after the group’s members were all convicted and sentenced to death at their first trial. Reich accessed Hamm’s testimony through civil rights activist Truman Nelson, who asked him to contribute a dramatic sound collage for a legal aid benefit.13 He agreed on the condition that he could use material from the tapes for another project. The original sound collage—which Reich dismissed as “pass the hat music”—has been heard by few beyond those present at the fundraiser, which was held at Town Hall, New York, in April 1966.14 Come Out remains one of his key early works, representing the synthesis of important technical and formal innovations that enabled his search for “a compositional process and a sounding music that are one and the same thing.”15 Chaotic, simple, and relevant, Come Out premiered in 1966 in New York’s Park Place Gallery to an interdisciplinary circle of artists, dancers, musicians, and filmmakers, many of whom were engaged in then-emergent Minimal, Process, and Conceptual art practices.16

Like his peers in the Minimal art and music scene, including Terry Riley and Donald Judd, Reich believed that authorial detachment could enable a kind of transcendental shift, as he claimed in his 1968 essay “Music as a Gradual Process”: “While performing and listening to gradual musical processes one can participate in a particularly liberating and impersonal kind of ritual. Focusing in on the musical process makes possible that shift of attention away from he and she and you and me outwards towards it.”17 Through an impersonal ritual, he argues, one can access the universal. Yet this failure to signify, characteristic of other Minimalist practices, suggests what James Meyer describes as the Minimalist work’s implicit negation of another reality, one to which it only obliquely alludes.18

Reich’s pointed interest in West African music, black vernacular speech, and radical New Left politics at a crucial moment early in his career stands in tension with his tepid interest in civil rights.19 Come Out is an ambiguous cultural text; as other scholars have observed, its unclear racial politics generate a site of interpretive struggle.20 Musicologists observe Reich’s preference to contextualize his speech compositions within a broader generational sentiment of cultural homelessness in the 1960s rather than in relation to African American civil rights. From 1961 to 1965, Reich lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, where he pursued graduate study at Mills College in Oakland, commingled with other artists and musicians, and immersed himself in beatnik countercultural endeavors.21 The rise of world music and developments in ethnomusicology, which expanded awareness of non-Western cultures at that time, led him to West African drumming and Balinese gamelan music, in which he identified technical commonalities with his own phase pieces.22 Through intensive study of these global rhythmic cultures, Reich embraced the ethnomusical traditions of his Jewish heritage in the 1970s.23 In other words, these traditions were a gateway for Reich’s autobiographical race consciousness, revealing themselves as imaginative investments from which he later distanced himself.24

On the one hand, Reich was skeptical of the power of art to effect political change.25 On the other, this case study reflects the historically ambivalent relationship between Jewish Americans and African Americans, described by many as a “special understanding” that has often been interpreted as being marked by patterns of alliance and betrayal.26 Within the American art world of the 1960s, Jewish intellectuals, artists, and critics often worked in solidarity with African American artists, and their artistic portrayals of racial issues tended to reflect the typically universalist interests of secular postenlightenment Jewish culture.27 In the decade more broadly, the rise of New Left politics, black nationalism, and the coalition building therein fueled a wave of ethnic revivalism in various heritage projects, in literature, and in popular culture that extended through the mid-1970s.28

Musicologist Sumanth Gopinath identifies three “race works,” all speech-collage tape-loop compositions, that catalyzed Reich’s early musical style (and by extension, Minimalist music).29 The first, It’s Gonna Rain (1965), featured the looped speech of Brother Walter, a black Pentecostal street preacher whose melodic sermon about the flood and the end of days caught Reich’s attention. Reich identified this work with a particularly visceral listening experience: “I had the stereo phones on and it felt like the sound was in the middle of my head. It seemed like it went from the left side of my head and down my arm and across the floor and then it began to reverberate.”30 At the same time, he was involved in a guerrilla-theater film collaboration, scoring the short film Oh Dem Watermelons! (1965), which featured an arrangement of singers in multipart canon performing two late nineteenth-century minstrel songs. Directed by Robert Nelson, it was included as an interlude in A Minstrel Show, or “Civil Rights in a Cracker Barrel” by the politically committed street-theater group known as the San Francisco Mime Troupe and toured nationally.31 Finally, Come Out (1966) was tied to the violent victimization of black bodies in resistance to the police state. But Reich focuses on musicality rather than metaphor or context in reflecting on this early work: “I did find this one little phrase through all this mountain of material where Daniel Hamm, who was one of the kids who, it turns out, did not do it, said, ‘I had to like open a bruise up and let the blood come out to show them I was bleeding.’ And that little phrase, ‘de dum ba de dum, come out to show them,’ caught my ear and I again made a tape loop piece.”32

When he published “Music as a Gradual Process,” Reich made no mention of the immediate sociopolitical conditions that gave rise to his techniques.33 Rather, he emphasized the generative paradox at the center of his compositional practice: “All music to some degree invites people to bring their own emotional life to it. My early pieces do that in an extreme form, but, paradoxically, they do so through a very rigid process, and it’s precisely the impersonality of that process that invites this very engaged psychological reaction.”34 The emphasis on process among Reich and his peers often concealed the contradictory desires of artists who, affiliated with both the political ideals of the New Left and the largely apolitical avant-garde tendencies within Minimalism and Process art, were unable to reconcile their political beliefs with their apolitical aesthetic commitments.35 Reich’s desire to invite a personal response through an impersonal compositional method, while compelling, offered a mechanism for maintaining safe distance from the intensifying political activism around civil rights and the Vietnam War, even as he instrumentalized black vernacular speech in the service of Minimalist music.

Ambivalence

The twentieth century was full of utopias; it has left us a large bequest of ambivalence.

—Kenneth Weisbrode, On Ambivalence: The Problems and Pleasures of Having It Both Ways36

Ambivalence describes a state of conflict in the human subject: the coexistence of opposed valences or desires. As such it has a strong psychological dimension (the term was first adopted for use in the early twentieth century as a symptom of schizophrenia), but I draw here on its relevance to the philosophical and political concerns of contemporary life.37 Although ambivalence has long been believed to be a trait that precludes rational thought and the unitary subject, ambivalence and rationality are co-constitutive of subjectivity. As philosopher Hili Razinsky argues, ambivalence is not exceptional but quotidian; it is multivalent in its scope (impacting emotion, factual belief, value judgment, and desire) and, most interestingly, it is a manifestation of unity in plurality: it must be understood both as the coexistence of two opposed attitudes toward the same object, and as a singular ambivalent attitude.38

Used frequently as a shorthand term for a person’s indecision, equivocation, or inaction, ambivalence is associated with inhibition. Yet assessing the Come Out paintings within Ligon’s broader oeuvre reveals ambivalence as a productive vehicle for keeping conflicting desires in suspension, of recognizing irreconcilable conditions in order to hold space beyond them. As a concept, it is endemic to the contemporary challenges presented by postmodernism and globalization, which demand that we learn to live in an incurably ambiguous world.39

Ligon incorporates ambivalence as a conceptual device to contain seemingly irreconcilable positions and forces—an embrace of contradiction that has become synonymous with his artistic practice.40 An ambivalent attitude is one that wants to have it both ways; in the Come Out paintings, for example, it is the desire to both conjure and abstract sound and body within a static, two-dimensional surface. It allows the representation of Hamm’s neglected subjectivity without spectacularizing his victimization, and acknowledges the futility of recuperation by rendering Hamm’s burden of proof as an inescapable, ongoing environmental condition.

In their monumental scale, the paintings physically overwhelm the viewer with Hamm’s words, amplifying his voice in space from singular, firsthand narrative to a collective call for resistance. Come Out #1, #2, #3, #10, and #12 (all 2014–15), each eight feet tall and twenty feet wide, envelop the viewing body in an immersive field whose pulsating optical quality recalls filmic and televisual interfaces. In Come Out #5 (2014), nearly eight feet tall and forty feet wide, text emerges from black ground as a rhythmic flicker from left to right. In their architectonic scale, the works ask the viewer to not only look but also mobilize the body in order to read the text, though the reading is visually confounding. The figure/ground relationship created by textual reproduction is not one of material accretion, as in Ligon’s earlier paintings, but rather that of atmospheric suspension to the point of noise, reflecting the sonically layered quality of Reich’s composition in the unexpected legibility of black-on-black.

How to care for the injured body,

the kind of body that can’t hold

the content it is living?

and where is the safest place when that place

must be someplace other than in the body?

—Claudia Rankine41

The seemingly permeable surfaces of Ligon’s Come Out paintings accommodate aspects of embodied experience that are unseen (but still felt and heard). Fred Moten reads this tactic of optical restraint as “tantamount to another, fugitive, sublimity altogether. Some/thing escapes in or through the object’s vestibule; the object vibrates against its frame like a resonator, and troubled air gets out. The air of the thing that escapes enframing is . . . an often unattended movement that accompanies largely unthought positions and appositions.”42 Ligon’s work transfers the bruise from Hamm’s body to the painting through the visual throb or dull stasis generated by abstract pulsations of language on the canvas.43 This reference restores the corporeal presence that Reich omits in his composition, but that constitutes its subject: the bruise blood is what would “come out to show them.” The bruise introduces a multivalent sense of bodily time, simultaneously registering injury and healing, and also indexing the trauma that often registers a psychic pain that outlives any physical trace. It is perpetually changing, emerging or fading, a site of fluidity and inflammation, transforming any skin tone into mottled shades of black, blue, and green.

In Reich’s music, the bodily quality of speech reenters by proxy, as a visceral experience transferred to the listener through the sensory vibration of resonance. But it was the racialized, corporeal violence behind Hamm’s utterance that the generative qualities of Come Out function to erase, putting Hamm’s words at a further remove as the track proceeds toward abstraction. Is Reich’s composition an anti-racist protest piece, or does it spectacularize and exploit black pain by psychically reenacting the primal scene of Hamm’s victimization and rendering it inaudible?44 Hamm’s original speech articulates one contradiction (harming one’s own body to save oneself), and Reich’s piece performs another (personal meaning crafted through impersonal processes); it is worth exploring Ligon’s pursuits in this vein.

Most broadly, Ligon posits visual representation and the power of the collective as driving forces of sociopolitical change, even when they fail. As Elizabeth Alexander reminds us, the rearticulation of bodily trauma in the public sphere produces a collective listening audience for whom the American national spectacle of the black body in pain is both ocular and auditory.45 What is transmissible about the body and its pain within the constraints of language? In absorbing Reich’s composition, what does Ligon’s visual mediation do for Hamm’s pain? The ceaseless repetition of “come out to show them” channels both the rhythm of Reich’s composition and of striking blows, signifying Hamm’s bodily suffering and the societal and psychological traumas that reverberate in the lives of descendants of African diasporic subjects in the United States.46 “You can think about hearing ‘I can’t breathe’ thirteen times,” Ligon noted, “if you want to get really perverse.”47 Referencing the death of Eric Garner by police chokehold in 2014, its recording by a civilian bystander, and the viral circulation of the video online, Ligon suggests the ambivalent conditions of mediated witnessing as an undeniable reality of contemporary life.

In Ligon’s paintings, however, there is no visible body in pain that feeds the consumerist spectacle of racial violence. Their covert oppositionality rests in refusal and disorder, symptomatic of what Fred Moten and Stefano Harvey call “the undercommons.”48 Perhaps these conditions are strategic—a form of self-erasure that subtracts the body from a sphere that denies its representation in any case.49 Insofar as Hamm’s verbal articulation of his own pain was not considered proof enough for police to take him to the hospital, insofar as his recorded testimony was not enough to prove police brutality in court, the failure of speech to communicate the truth of racial violence demands new modes of signification. Ligon is interested in the failure of communicative forms such as letters, numbers, and documentary photography due to the contradictory ideas that emerge from failure: “the idea of saying something over and over and not being heard. The idea of being heard and not being heard.”50 He has frequently stated his attraction to “flaws in reproduction”—whether newspaper reproductions of distorted microfilm or audiovisual glitches, recounting that he liked “when the pictures ‘fell apart.’”51 In the Come Out paintings, misregistration—often perceived as a flaw in commercial print reproduction—produces the textual excess that causes visual reverberation in the paintings. Channeling something phenomenological akin to what Reich described as a visceral listening experience, Ligon exploits the silkscreen’s lo-fi quality to call up “a third thing” that emerges between matrix and surface.52

Andy Warhol, who so masterfully pushed the silkscreen medium toward a symphonic articulation of fatigue, trauma, and the particularly American appetite for producing and consuming violence, lurks in the shadows of these paintings. For Warhol, as for Reich, the evacuation of traumatic content through its repetition may appear to extinguish meaning but nonetheless registers its overwhelming social effects—it is “just part of the scene,” in Warhol’s words.53 Though Ligon does not traffic in the visual spectacle of suffering, he appreciates the serious irony endemic to Warhol’s art and life, stating: “To make a career out of being fascinated with one’s own disappearance is quite a feat. I realized that if disappearance could be a subject matter, I could be an artist.”54 Disappearing his own authorial presence, visualizing the disappearance of voice, registering the disappearance of black life and its historical memory, Ligon’s loss-ridden artworks find productive ambivalence in monumentalizing Hamm’s speech through the legibility errors of the reproductive medium, acknowledging its inherent fragmentation and incompleteness.

Ligon also recognizes the impossibility of reclaiming Hamm’s subjectivity or identity through the reproduction of his voice alone, since voice, as musicologist Nina Sun Eidsheim argues, is not a reliable signifier of identity but rather a “complex event” whose meaning is materially contingent and socially produced.55 Yet, still, we ask the question of “who” it is, and just as our eyes are trained to objectify race on the visual skin surface, our ears are trained to recognize nonwhite vocal timbre: a voice that “sounds black” registers as such because vocal timbre and racial meaning are connected through assumptions about authenticity and racial essentialism. Blackness, if it can be ascertained through vocal timbre alone, can exist without a black body to hold it—a condition Eidsheim describes as “acousmatic blackness.”56

Whether or not one knows of Ligon’s link to Reich, his quotational practice constructs an audience of its own.57 The phrase “come out to show them” could easily be a rallying cry for the radical left-wing activist movements that galvanized, yet often divided, communities in the late 1960s around a range of liberation movements, or for the various projects of identity politics that revisited those histories in the 1990s when Ligon (as an artist who self-identifies as a black gay male) was beginning his career.58 The phrase also conjures the LGBTQ parlance, “coming out,” a late twentieth-century call to shed social stigmas through self-disclosure, making otherwise marginalized or threatened identities known visibly, publicly, and proudly. By far the most pressing collective energy in Come Out’s genesis was the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of the 2013 killing of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black seventeen-year-old in Florida. The deaths of Michael Brown (eighteen years old) in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner (age forty-three) in New York City in 2014 ignited major protests in the United States around the use of excessive force by police and civilians toward unarmed black men, youth, and women.

Ligon also identifies the contradiction of Reich’s sound composition as historical archive: it effaces Hamms’s voice, yet as a major twentieth-century artwork, it stands as one of the major conduits of the story of the Harlem Six—albeit an extremely fragmentary one.59 He credits Reich for the structure of his Come Out paintings, but their content was driven by the various textures of public discourse that framed the Harlem Six for the listening public.60 Ligon frequently leverages historical gaps between his art and its source texts to question how contemporary voices and identities are formed, locating the artist between representer and represented.61 Ligon’s selection of source texts has invited a range of teleological, linguistic, and psychoanalytic interpretations of his subjecthood. As Lauren Deland notes, Ligon’s own body represents “not a unitary self, but a dialogic, citational, and wholly subjective being-for-others,” reflecting Frantz Fanon’s notions of split subjectivity and the self-negation of the black subject under the white gaze.62 In this case, Ligon’s voice is suspended too, sometimes ambivalently, between the voice of Reich (as a Minimalist and Conceptual artist) and Hamm (as a black man).

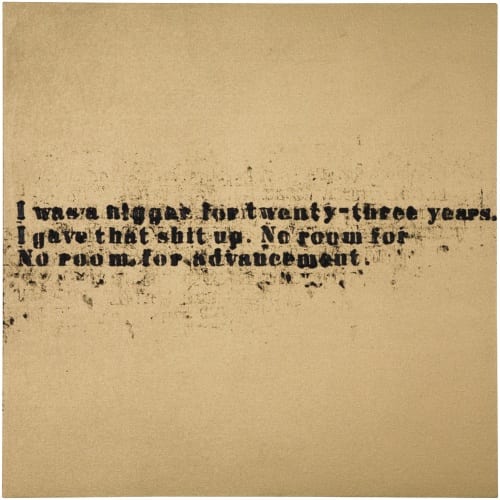

Lastly, Ligon pursues the challenge of getting sound into painting. Though often aligned with literary interest, Ligon also integrates listening—which incorporates physical, psychological, and emotional effects—as a method of citation.63 The Pryor paintings, for example, a series of text paintings initiated in the early 1990s and revisited in 2004, were produced while listening to records of comedian Richard Pryor’s controversial stand-up routines.64 In the first series, the aural tone of Pryor’s delivery and his particular style of off-color humor—trenchant, vulgar, and often shocking—translates to a chromatic and rhetorical discomfort. The resulting paintings induce an “optics of struggle” that dissociates voice from speaker and onto reader, conscripting the viewer in the public consumption and internalization of the stereotype.65 In transcribing Pryor’s speech delivery, including its irregularities, Ligon engages the performativity of the body and the voice. In No Room (Gold) #21, the text reads as follows: “I was a nigger for twenty-three years. I gave that shit up. No room for No room for advancement.” The repetition of the phrase “No room for” is an exact representation of Pryor’s recorded speech, in which he stutters in his delivery. The resplendent setting of the text, centered on a square gold canvas, contradicts the joke’s flip reference to one’s failure to climb the corporate ladder of racial equality. This body of work, through color harmonics and text arrangement, attempts to get sound into the painting without actually using sound, and to evoke the tempo and tone of spoken language.66

Interpreting the atmospheric and sonorous qualities of Hamm’s testimony through painting rather than a time-based medium, Ligon creates an intermedial archive that keeps Hamm’s speech in a state of suspension rather than erasure, and monumentalizes the description of Hamm’s forced self-harm as symptomatic of a self-negation that extends far beyond the individual experience. Rather than ask us to witness the obfuscation of Hamm’s voice over time, the Come Out paintings freeze multiple moments in the process of abstraction, destabilizing the notion of a singular present and offering, to quote Michael Warner, “a speech for which there is yet no scene, and a scene for which there is no speech.”67 Beyond producing visual corollaries for moments of aural superimposition, Ligon’s paintings center Reich’s ambivalence in their dynamic of withholding and revelation. It is in probing the distinction between speech and voice that Reich’s ambivalence emerges.

For Reich, speech was a fascinating raw material that offered two signifying layers of emotion and content that instrumental music could not provide. As such, he was committed to reproducing speech without altering pitch or timbre, in order to “keep the original emotional power that speech has while intensifying its melody and meaning through repetition and rhythm.”68 Black vernacular speech was uniquely melodic, as Reich observed about Brother Walter’s Pentecostal sermonizing in It’s Gonna Rain: “it was something that hovered between music and speech.”69 Yet, Reich’s interest in black speech but not the black subject verges on the primitivization of minority cultures in the history of modern art, including the fascination within the American counterculture with Eastern spiritual liberation. Reich’s own feelings of collective and personal loss in 1965—he cited the ongoing Cold War and his divorce—shaped his decision to evoke the feeling, in his early tape works, that “you’re going through the cataclysm, you’re experiencing what it’s like to have everything dissolve.”70

Ligon registers Hamm’s synecdochic presence as almost infinitely split, sublimated in its fragmentation, reflecting the paradox of Reich’s composition as a vehicle of preservation and erasure. Reich describes the transformation of voice in his early phase pieces in marvelous terms, invoking the notion of witnessing an other in the process of coming apart: “When the persona begins to spread and multiply and come apart, as it does in It’s Gonna Rain, there’s a very strong identification of a human being going through this uncommon magic.”71 Does this uncommon magic of dissolution induce pleasure?72 Or, as this essay has queried, was Reich’s listening situated ambivalently between fascination, opportunism, and a racializing ear? As literary scholar Jennifer Lynn Stoever observes, “Listening—as both an epistemology and technology—also produces race, and ideologies of race have a profound (and widely divergent) impact on how people listen, how they imagine others to listen, and, most importantly, whose screams they deem worth heeding.”73 Reich’s Come Out preserves both the echo and erosion of Hamm’s voice as a paradoxical truth that, in Ligon’s listening to it, admits the impossibility of knowing the subject of the documentary source. Ligon’s paintings rematerialize Hamm’s words as force fields that waver with uncertainty or vibrate with energy, engulfing their viewer with a chorus that casts Hamm’s burden of proof from his body into an environmental condition that feels inescapable.

photograph provided by the artist, Hauser & Wirth, New York, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, and Chantal Crousel, Paris)

Isn’t it possible that blackness has always contained within itself its own

diffusion?

—William Pope.L74

The web of appropriation, repetition, translation, and diffusion constructed between Ligon’s paintings, Reich’s sound composition, and Hamm’s original speech act creates a field of mediation that distances the art object from its origin point: the voice of the black body in pain, the body that must provide corporeal evidence of its pain in spite of that voice. Created nearly fifty years apart, both works appropriate language and, through repetition, drive its sublimation. Rather than neatly conclude this essay, it seems more appropriate to retain these two works in suspension. Reading Come Out in a way that accounts for Reich’s belief that aspects of process translate to aesthetic experience—“a compositional process and a sounding music that are one and the same thing”—suggests, in the composition’s methodical repetition of Hamm’s utterance, a rehearsal of his pain. Within Ligon’s practice, the sonic domain is both literal and implied, and serves to complicate the already troubled terrain and logic of the visual.75 Ligon often situates interrogations of race, gender, and identity against seemingly stable grounds—such as history, masculinity, visibility, or humor—that reveal themselves to be constantly shifting and in need of sustained interrogation. One such ground is reconciliation; the Come Out paintings, in their various states of irreconcilability, posit ambivalence as a state of psychological conflict and ethical tension, and an unavoidable way of being in the world.

Ellen Y. Tani is an art historian and curator based in Boston. She earned her PhD in art history in 2015 from Stanford University. Her research includes contemporary African diasporic art, conceptual practices, performance, and modern and contemporary American art. Her work has been published in American Quarterly, Apricota, and exhibition monographs on Senga Nengudi and Charles Gaines.

This article began as a curatorial pairing of Come Out by Steve Reich and Come Out #6 by Glenn Ligon that I conceived in the 2018 exhibition Second Sight: The Paradox of Vision in Contemporary Art at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. I extend my gratitude to Cherise Smith, who convened the panel “‘Change the Joke, Slip the Yoke’ Twenty Years Later” at the CAA Annual Conference in 2018 with the support of Jessi DiTillio. I am grateful to our respondent, Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw; my copanelists, Tiffany Barber and Christina Knight; and Art Journal’s readers, who provided valuable feedback as this text developed.

- “Excerpts from an Interview in Artforum” (1972), in Steve Reich, Writings on Music, 1965–2000, ed. Paul Hillier (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 33. ↩

- Steve Reich, Come Out, with Daniel Hamm (voice), 1966, on Early Works, Elektra Nonesuch 9 79169-2, 1987, compact disc. ↩

- Phasing introduced sampling to American music, influencing dub, hip-hop, and electronic music, and was elemental to Minimalist music, known for its rule-based compositional processes, which eschewed narrative and defamiliarized the listening experience. Reich, along with Terry Riley, Phillip Glass, and LaMonte Young, all used repetition and found sound to develop this experimental style. ↩

- Then just seventeen years old, Hamm was arrested with several other young men (Wallace Baker, Frederick Frazer, Fecundo Acion, and Frank Stafford). According to Hamm’s testimony, recorded by Willie Jones, a social worker from Harlem Youth Unlimited, on April 20, 1964: “We went to the precinct and that’s where they beat us, like 12 and 6 at a time would beat us and this went on practically all that day when we were in the station. Fortunately, when they threw us on the floor, I was fortunate enough to crawl under the bench so I wouldn’t get whipped so bad. They beat me till I couldn’t barely walk and my back was in pain.” Quoted in Junius Griffin, “Harlem: The Tension Underneath; Youths Study Karate, Police Keep Watch and People Worry,” New York Times, May 29, 1964. Griffin’s article, illustrated by images of black youth practicing karate, has been criticized for associating the men with alleged gang membership and stoking fears about antiwhite sentiment. ↩

- Glenn Ligon, interview with the author, August 2, 2018. ↩

- The Come Out paintings debuted in in 2014 at Thomas Dane Gallery, London (Glenn Ligon: Come Out, February 12–March 22, 2014), and Camden Arts Centre, London (Glenn Ligon: Call and Response, October 10, 2014–January 11, 2015); they were first shown in the United States in 2015 at Regen Projects, Los Angeles (Well, It’s Bye-Bye/If You Call That Gone, March 14–April 18, 2015). See Megan Ratner, Glenn Ligon: Come Out, exh. cat. (London: Ridinghouse, 2014). Four of Ligon’s paintings occupied a gallery of the Central Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2015, and his neon sculpture of the words “blues blood bruise” (based on a perceived malapropism in Hamm’s speech, which to Ligon sounded like “blues blood” instead of “bruise blood”), appeared in the place of the main signage for the Biennale on the building’s facade. ↩

- Janet Kraynak, “How to Hear What Is Not Heard: Glenn Ligon, Steve Reich, and the Audible Past,” Grey Room 70 (Winter 2018): 62. ↩

- Moiré is the dizzying, harmonic optical effect produced by interference, in which two similar patterns are overlaid upon one another. ↩

- Discussing the conceptual practice of Charles Gaines, Moten writes: “What if the true complexity of the work of art that is revealed in criticism is that art always exceeds the work, not as its absence but, rather, as its irreducibly present madness?” Fred Moten, Black and Blur (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 260. ↩

- Carl Suddler, “The Color of Justice without Prejudice: Youth, Race, and Crime in the Case of the Harlem Six,” American Studies 57, no. 1/2 (2018): 57–78. The Harlem Six—William Craig, Wallace Baker, Walter Thomas, Ronald Felder (all released 1973), Daniel Hamm (released 1974), and Robert Rice (released 1991)—were originally sentenced to death but later granted a retrial. Key historic accounts of the Harlem Six can be found in There Is a Fountain: The Autobiography of a Civil Rights Lawyer (Westport, CT: L. Hill, 1979), by Conrad J. Lynn, an African American civil rights lawyer who believed the Harlem Six had been framed and who led their appeal and retrial with lawyer William Kunstler; and The Torture of Mothers (Boston: Beacon, 1968), by Truman Nelson. ↩

- James Baldwin, “A Report from Occupied Territory,” Nation, July 11, 1966. ↩

- Suddler, “Color of Justice.” Citing a dramatic rise in crime since the turn of the twentieth century, civic leadership in New York supported increased policing, particularly in advance of the 1964 World’s Fair. ↩

- Sumanth Gopinath chronicles the origin of the sound collage in the greatest detail, in “The Problem of the Political in Steve Reich’s Come Out (1966),” in Sound Commitments: Avant-Garde Music and the Sixties, ed. Robert Adlington (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 121–44. ↩

- John Pymm has recently published the most thorough discussion of the original sound collage, entitled The Harlem Six Condemned, which is housed in an archive in Switzerland. See Pymm, “Steve Reich’s Dramatic Sound Collage for the Harlem Six: Toward a Prehistory of Come Out,” in Rethinking Reich, ed. Sumanth Gopinath and Psyll ap Siôn (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 139–57. ↩

- Edward Strickland, American Composers: Dialogues on Contemporary Music (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 40; Steve Reich, “Music as a Gradual Process” (October 1968), in Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials, by James K. Monte and Marcia Tucker, exh. cat. (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1969), 57. For example, achieving sonic abstraction without altering pitch, tone, or timbre signaled a more controlled approach to process than the aleatory methods of many of Reich’s avant-garde contemporaries, like John Cage, and resisted the unrecognizable content of most musique concrète tape music. ↩

- Steve Reich, interview with Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, 2008, http://www.stevereich.com/. See also Ross Graham Cole, “Illusion/Anti-Illusion: The Music of Steve Reich in Context,1965–1968” (MA thesis, University of York, 2010). ↩

- Reich, “Gradual Process,” 57. ↩

- James Meyer, Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 187. ↩

- Reich cites A. M. Jones’s book Studies in African Music (1959), which he read while in graduate school in 1962; he was “fascinated with the relationships between the tape loops and the African use of independent repetition of simultaneous patterns.” Reich, Writings on Music, 10. ↩

- See Gopinath, “Problem of the Political”; Sumanth Gopinath, “Reich in Blackface: Oh Dem Watermelons and Radical Minstrelsy in the 1960s,” Journal for the Society for American Music 5, no. 2 (2011): 139–93; Lloyd Whitesell, “White Noise: Race and Erasure in the Cultural Avant-Garde,” American Music 19, no. 2 (Summer 2001): 168–89; Martin Scherzinger, “Curious Intersections, Uncommon Magic: Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain,” Current Musicology, no. 79/80 (2005): 207–44; and David Schiff, “A Rebel in Defense of Tradition,” Nation, October 19, 2006. ↩

- In the Bay Area, Reich started a musical ensemble, became involved with the San Francisco Jazz Workshop, where he heard John Coltrane perform, and assisted Terry Riley on the 1964 premiere of In C at the San Francisco Tape Music Center. Riley had approached Reich after attending a performance of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, a radical theater group with whom Reich regularly collaborated and where he in turn met filmmaker Robert Nelson. It would have been difficult for Reich to ignore the racial tensions in Oakland while in graduate school in the wake of urban renewal projects that predominantly displaced people of color and fueled intensifying conflicts between the growing black population and primarily white police force, presaging the founding of the Black Panther Party in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. ↩

- Reich, quoted in Jonathan Cott, “Interview with Steve Reich,” in Reich, Works, 1965–1995, Nonesuch – 79451-2, 1997, compact disc, notes, 36–37. ↩

- As Gopinath (“Problem of the Political”; “Reich in Blackface”), Whitesell (“White Noise”), and Scherzinger (“Curious Intersections”) acknowledge, new scholarship in ethnomusicology in the 1960s introduced global music culture to a generation of musicians and artists then actively seeking a foundation of cultural identity. As Reich reflected, “People raised in the 1950s and 60s, like myself, often felt they were ‘without a home, a complete unknown’—there was no ethnic underpinning. I simply had to discover where I came from, which was very satisfying and allowed me to learn things about Judaism that have become very important in my life” (Reich, Works, 1965–1995, 38). Reich traveled to Ghana and Bali in the 1970s to study percussion ensemble music. He recalled asking: “Don’t I have any kind of oral tradition in my life? I began to realize as a Jew, I’m a member of one of the oldest existing groups . . . and I don’t know anything about it.” He later converted to Orthodox Judaism, studied Jewish cantillation in Israel, and composed the Grammy-nominated piece Different Trains (1988). Q (CBC radio program), “Steve Reich Reflects on His Most Significant Works,” April 14, 2016. ↩

- Reich’s attraction to black culture aligns with the broader fascination among the New Left with non-Western religions and minority cultural practices; Robert Nelson, Reich’s close collaborator at the time, shared that Reich was “involved in an idealization of blackness.” Cole, Illusion/Anti-Illusion, 45. ↩

- John Pymm, “Steve Reich’s Dramatic Sound Collage for the Harlem Six: Towards a Prehistory of Come Out,” in Rethinking Reich, ed. Gopinath and Siôn, 142. ↩

- Robert Weisbord and Arthur Stein, Bittersweet Encounter: The Afro-American and the American Jew (Westport, CT: Negro Universities Press, 1970). See also Jeffrey Melnick, “Black & Jew Blues,” review, Transition 62 (1993): 106–21. ↩

- Milly Heyd, Mutual Reflections: Jews and Blacks in American Art (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1999), 17. ↩

- Matthew Frye Jacobsen, Roots Too: White Ethnic Revival in Post–Civil Rights America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 17. Jacobsen cites Alex Haley’s Roots, Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood among Ghosts, and Irving Howe’s World of Our Fathers, all first published in 1976. ↩

- Gopinath, “Reich in Blackface,” 140. ↩

- Gabrielle Zuckerman, “An Interview with Steve Reich,” American Public Media, July 2002. ↩

- The singers initially hummed Stephen Foster’s song “Massa’s in de Cold Ground” (1852) and then sang Luke Schoolcraft’s “Oh! Dat Watermelon” (1874). Oh Dem Watermelons! was released as an independent experimental film; it won the award in the “Cinema as Art” category of the San Francisco Film Festival in 1965. Reich composed the music for the live performances and created the soundtrack for the film’s distribution. The live production featured the troupe’s interracial cast (some of whom were affiliated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) in blackface, in an ironic send-up of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century minstrelsy genre. The goal was to critique white liberal racism in America and “explode stereotypes” using satire and radical leftist politics, confronting the audience with culturally repressed tropes. Nelson’s film, which screened during intermission, featured watermelons being variously handled or destroyed (cut, sliced, and exploded). See Gopinath, “Reich in Blackface,” 147–62. ↩

- Steve Reich, interview with Ev Grimes, December 15–16, 1987, quoted in Gopinath, “Problem of the Political,” 127. ↩

- Gopinath, “Reich in Blackface,” 166–67; Scherzinger, “Curious Intersections,” 215. ↩

- Reich, Works, 1965–1995, 29. ↩

- Robert Adlington, “Introduction: Avant-Garde Music and the Sixties,” in Sound Commitments, 4. ↩

- Weisbrode continues: “If globalization, then, stands for nothing less than the universal application of e pluribus unum {out of many}, what are we to make of the certainties of time and space in the contemporary world? Surely globalization begets and reinforces ambivalence. Its emphasis, even dependence, on interconnectivity, interchangeability, ‘hybridity,’ and so forth leaves many of us with a sense of loss of place, space, linear time,” Kenneth Weisbrode, On Ambivalence: The Problems and Pleasures of Having It Both Ways (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 56. ↩

- The use of ambivalence in this sense was introduced in 1908 by Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler as one of the fundamental disturbances behind a series of disorders that he named “the schizophrenias” (autism, denoting the loss of contact with reality; ambivalence, denoting the coexistence of mutually exclusive contradictions within the psyche; affect; and association), formerly thought of as a singular disease, dementia praecox. Bleuler—also a eugenicist who advocated the sterilization of schizophrenics—was an acolyte of Sigmund Freud early in his career and later employed Carl Jung as his assistant. Encyclopedia Brittanica, s.v. “Eugen Bleuler”; see also Weisbrode, On Ambivalence, 11. ↩

- Hili Razinsky, Ambivalence: A Philosophical Exploration (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield International, 2016), 98. See also Philip J. Koch, “Emotional Ambivalence,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 48, no. 2 (December 1987): 257–79. ↩

- Zygmunt Bauman, “Modernity and Ambivalence,” Theory, Culture & Society 7, no. 2–3 (1990): 143–69. ↩

- See Darby English, “Glenn Ligon: Committed to Difficulty,” in Glenn Ligon: Some Changes, by Wayne Baerwaldt et al., exh. cat. (Toronto: Power Plant, 2005), 44. ↩

- Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric (London: Penguin, 2015), 143. ↩

- Fred Moten, “The Case of Blackness,” Criticism 50, no. 2 (Spring 2008): 182. Here Moten reflects on Frantz Fanon’s ambivalence in “The Lived Experience of the Black,” from Black Skin, White Masks (1952), and posits a philosophy of reading the black in the black experience. ↩

- Mickey Valée reads the politicization of Hamm’s body through the bruise in “The Rhythm of Echoes and Echoes of Violence,” Theory, Culture & Society 34, no. 1 (2017): 97–114. ↩

- As Janet Kraynak (“How to Hear”) has more pointedly asked: “Does Reich’s remediation mitigate racial conflict and in so doing (again) render black subjectivity inaudible?” (63). David Joselit issues a similar query about the artistic reproduction of racial stereotype in the work of Kara Walker: “Is reiterating a visual stereotype a subversive act or does it merely extend the violence of a crude slur?” Joselit, “Notes on Surface: Toward a Genealogy of Flatness,” Art History 23, no. 1 (March 2000): 30. ↩

- Elizabeth Alexander, “Can You Be BLACK and Look at This? Reading the Rodney King Video(s),” in The Black Public Sphere: A Public Culture Book (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 82, 84. Originally published in Public Culture 7, no. 1 (1994): 77–94. ↩

- Darby English cautions against the temptation to read iconic victimhood and racial violence as the only grounds against which to measure the black subject’s identity. See English, “Emmett Till Ever After,” in Black Is, Black Ain’t, ed. Hamza Walker and Karen Reimer, exh. cat (Chicago: Renaissance Society, 2013), 84–99. ↩

- Glenn Ligon, interview with the author, August 2, 2018. ↩

- Jack Halberstam, introduction to The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study, by Stefano Harvey and Fred Moten (Wivenhoe, UK: Minor Compositions, 2013). ↩

- Huey Copeland describes Ligon’s commitment to fugitivity as “a transitory state of being, a way of wandering to survive, and a protocol of reading—that emerges as a critical response to the black subject’s positioning on the margins of the human in the modern West.” Copeland, Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 121. See also David Joselit, “Material Witness: David Joselit on Visual Evidence and the Case of Eric Garner,” Artforum 53, no. 6 (February 2015): 202–5. ↩

- Glenn Ligon, “Interview with Andrea Miller-Keller,” in Yourself in the World: Selected Writings and Interviews, by Glenn Ligon (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 71. ↩

- Quoted in Scott Rothkopf, “Glenn Ligon: AMERICA,” in Glenn Ligon: AMERICA, ed. Scott Rothkopf, exh. cat. (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2011), 37. Ligon nods explicitly to audiovisual glitches in the titles of paintings such as Dispatches (2011) and Static (2008), and the volatility of analog film in Death of Tom (2008), his first film project, which emerged out of processing failure: “The film was just blurry, fluttery, burnt-out black-and-white images, all light and shadows. But I thought that failure of representation was in line with my larger artistic project, which has always been about turning something legible like text into an abstraction.” Glenn Ligon, “Interview with Jason Moran,” in Yourself in the World, 176. ↩

- Glenn Ligon, interview with the author, August 2, 2018. ↩

- Andy Warhol, interview with G. R. Swenson, in “What Is Pop Art? Answers from 8 Painters, Part I,” Artnews, November 1963, repr. in I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews, 1962–1987, ed. Kenneth Goldsmith (New York: Carroll & Graff, 2004), 18. Scherzinger, “Curious Intersections,” 228. ↩

- Glenn Ligon, “Untitled (2008),” in Ligon, Yourself in the World, 30. ↩

- Eidsheim defines the acousmatic question—or what we can hear but cannot see—as something we ask because “voice and vocal identity are not situated at a unified locus that can be unilaterally identified. We ask the acousmatic question because it is not possible to know voice, vocal identity, and meaning as such; we can know them only in their multidimensional, always unfolding processes and practices, indeed in their multiplicities. This fundamental instability is why we keep asking the acousmatic question.” Nina Sun Eidsheim, The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 3. See also Brian Kane, Sound Unseen: Acousmatic Sound in Theory and Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014). ↩

- Eidsheim, Race of Sound, 7. ↩

- Aligning quotational speech with protest speech, Patrick Greaney draws parallels between Ligon’s construction of an audience and the subtle oppositional intent of his work. Greaney, Quotational Practices: Repeating the Future in Contemporary Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 153. ↩

- Copeland offers a detailed analysis of Ligon’s positionality within the 1990s New York art world in Bound to Appear, 109–50. ↩

- Gopinath, “Problem of the Political,” 121. ↩

- As Ligon recalled, “Reich was structure, Baldwin and Lynn were content.” Quoted in Kraynak, “How to Hear,” 65. ↩

- English, “Committed to Difficulty,” 38. ↩

- Lauren Deland links Ligon’s citational practice to Frantz Fanon’s observation in Black Skin, White Masks that the white gaze both surveils the black man’s body as an object to be seen and renders his subjectivity invisible, effectively splitting the psychic self in two. Deland, “Black Skin, Black Masks: The Citational Self in the Work of Glenn Ligon,” Criticism 54, no. 4 (Fall 2012): 517. ↩

- Glenn Ligon, nterview with the author, August 2, 2018. ↩

- Ligon had worked with sound in the 1992 sculptural work To Disembark, which explored the lore of Henry Box Brown, a former slave who apparently emerged singing from the box in which he shipped himself from the South into northern states. See Copeland, Bound to Appear, 109–52. ↩

- Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 245–52. ↩

- Glenn Ligon, nterview with the author, August 2, 2018. ↩

- Warner, quoted in Greaney, Quotational Practices, xiv. ↩

- See Reich, Writings on Music, 20; and quoted by Keith Potter, Kyle Gann, and Pwyll ap Siôn, in introduction to The Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music, ed. Potter, Gann, and Siôn (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2013), 29. ↩

- Quoted in Emily Wasserman, “An Interview with Steve Reich,” Artforum 10, no. 9 (May 1972), 44. Scherzinger, “Curious Intersections,” 218. ↩

- Reich, Writings on Music, 21. ↩

- Reich (2002), quoted in Scherzinger, “Curious Intersections,” 216. ↩

- What Reich may allude to, perhaps unknowingly, is the psychological effect of listening to Minimalist music: it triggers right-brain perception, which involves feeling “lost” in a nonverbal world of feeling and atmosphere, and also losing a sense of time. According to Potter, Gann, and Siôn, there is a visceral form of pleasure associated with Minimalist music; the phasing process in Come Out “tonalizes the spoken phrase, abstracting pitches and contours from its verbal meaning and changing our perception of the phrase. . . . The particular pleasure here is difficult to verbalize: evidence that the right brain is involved. At some point we can hardly believe that the transformations all stem from the simple phrase we heard in unison at the beginning. Our analytical understanding can hardly account for our sensuous fascination” (Research Companion, 9). ↩

- Stoever describes the threshold between musical production and consumption, shaped by the subconscious mechanisms that are ingrained in how we speak, listen, and thus racialize certain communication, as “the sonic color line.” Jennifer Lynn Stoever, The Sonic Color Line: Race and the Cultural Politics of Listening (New York: New York University Press, 2016), 260. For an art historical corollary, see Jacqueline Francis, Making Race: Modernism and “Racial Art” in America (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012). See also Alexander Weheliye, Phonographies: Grooves in Sonic Afro-Modernity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005); and Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003). ↩

- William Pope.L, “Some Notes on the Ocean. . . ,” in Glenn Ligon: Encounters and Collisions, ed. Glenn Ligon, Alex Farquharson, and Francesco Manacora, exh. cat. (London: Tate Publishing, 2015), 158. Originally published in 2005 in the exhibition catalog William Pope.L: Some Things You Can Do with Blackness, exh. cat. (London: Kenny Schacter Rove, 2005). ↩

- Copeland, Bound to Appear, refers to this as “aesthetic remixing” (15). ↩