Download the open edition script here.

Liz Magic Laser’s Flight at Times Square Alliance.

InterAct

a reenacted interview

Produced by Christopher Y. Lew

Directed by Liz Magic Laser

WITH

Nic Grelli, Elizabeth Hodur, Liz (Lizzie) Micek,

Michael Wiener, Lia Woertendyke, and Max Woertendyke

Photography by Mia Tramz

Special thanks to Tom Williams for editorial advice

TABLE OF SCENES

ACT I

The producer, director, and cast meet at the East River Park Amphitheater in

New York City on September 18, 2010.

The morning is cool, sunny, and dry. The right weather for retrospection.

The assembled group sits in the bleachers.

A conversation about the group’s endeavors takes place.

This conversation is recorded and subsequently transcribed.

ACT II

The group re-assembles on October 3, 2010. Same time. Same place.

They meet on the amphitheater stage to reenact the edited transcript

of the previous encounter.

Introduction to InterAct:

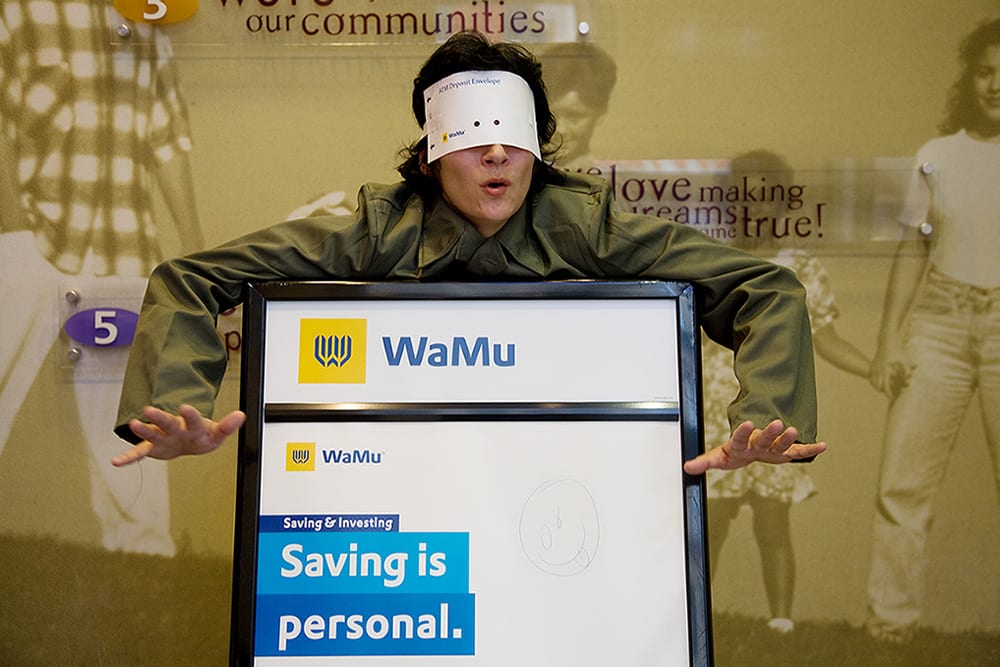

If the world’s a stage, then Liz Magic Laser becomes its director and all passersby are forced to perform. In 2009 Laser staged chase; the following year she produced Flight: in both works, action was registered on video and video begat action. For chase, the houses of finance in the City of New York provided platforms for Man Equals Man, Bertolt Brecht’s 1926 play. Nine actors performed within Automated Teller Machine vestibules, each one separated from the next, practicing alone his or her role for the bank’s machines and patrons. During the chase exhibition opening, Laser and the cast staged a live production of Elephant Calf, a play within Brecht’s original play, at Derek Eller Gallery.

Six actors performed Flight on the courtyard staircase of MoMA PS1, repurposing foot chases from films such as Battleship Potemkin, M, American Psycho, Niagara, and Scream. During these sequences, the pursuer in one scene often became pursued in the next. Aggressors became victims and onlookers turned into perpetrators. This May Flight comes to Times Square in the heart of New York City’s theater district.

To produce Interact, this project for Art Journal, Laser and her cast met at the East River Park Amphitheater on two mornings last autumn: the first time to talk in the bleachers and the second time to relive the first conversation on stage.

PRELUDE

Liz: An interview produces a script and this script produced an interview.

Chris: We write what we speak and speak what we write.

Liz: Brecht thought you don’t say what you think, but rather you come to think what you say.

Chris: And how does the hand that writes figure into this?

Liz: The hand envies the mouth and the mouth the hand.

ACT I

An amphitheater in New York City. Early autumn. Late morning. In the bleachers.

ACT II

Two weeks later. Same time. Same place. On amphitheater stage.

SCENE I: The Theatrical Interface

[Upstage lights come up. Chris and Liz enter from stage right, followed by Elizabeth and Michael. Max enters from stage left, then Lia enters from stage right. Nic and Lizzie straggle in last from stage right. They gather center stage as if it were in a line-up, with scripts in hand. From stage right: Liz, Lizzie, Elizabeth, Michael, Lia, Nic, Max and Chris.]

Michael: It’s curious how we’ve entered this naturalized theatrical space today. And yet here we are sitting and it seems unnatural, I don’t feel like I’m performing but there is an element of…

Lia: Urgency?

Chris: Maybe for Act II we’ll feel more of that…

Liz: I thought it would be natural to use the strategies we developed during these last two projects in order to process the work together… Let’s move a little closer.

[All draw closer together, closing in on the microphone.]

SCENE II: Artist as Director

[Everyone is fidgeting to keep warm.]

Chris: [Kicking up his heels restlessly] Both chase and Flight are about performance—Flight is enacted live and chase intervenes into very public spaces. But the artist driving the work is not necessarily present or at least visible. So what does it mean when the artist is not there and is functioning more as director?

Liz: Well Flight was tightly rehearsed and then on the day-of I had to step back, but in the case of chase it felt like we were performing together to some degree because of my role with the video camera.

Max: And you became a character too.

Liz: Yes, sometimes I asked you to deliver your lines to my machine. It was a partnership; together we’d go in and instigate an antagonistic interaction with someone trying to get money from the ATM. My intrusion with the camera was delivered in tandem with your verbal intrusion.

Max: It was the camera that was more upsetting to people than the dialogue.

Elizabeth: Even though you were speaking in archaic language?

Max: Yes, someone talking is just a distraction, but someone with a camera is more of an intrusion.

Lizzie: You set the stage for what people would see when they walked into the bank. They had no idea what they were walking into. Like the time the guy came out and asked, “Who has the camera?! Get out!” You played a role in all that, in the way the event unfolded.

Liz: That’s true. With Max and Lizzie we were repeatedly expelled. It was very much about being prepared for that scenario when someone points at you and says, “No! You can’t do that!”

Lizzie: And they would be pointing at you.

Liz: Can you specify for our audience who you are referring to?

Lizzie: You [points menacingly towards Liz].

Liz: Yes. One time with Lizzie the bank manager threatened to take my camera away. He wanted us to come discuss it in the backroom.

Elizabeth: Oh my gosh [astonishment and laughter].

Liz: In the bank our rehearsing and performing became one process. Because of the nature of the semi-public space, we learned how to respond when someone says, “You’re in trouble! No!” I would say, “It’s okay. We’re leaving. It’s okay.” And they would get confused and say, “But I’m telling you it’s not okay… You can’t tell me it’s okay…”

Chris: So you came prepared for what you couldn’t control?

Liz: We were teaching ourselves how to engage differently with power dynamics in a space that feels controlled. [Using right hand expressively] But it also felt like something unexpected could always happen. There was a risk.

Nic: [Steps forward] In Flight the dynamic with the audience totally changed. We did have a certain amount of control over the situation. But then the audience arrived. Each time Liz had to give that control over to us and we gave it over to the crowd. So even if you gave us directions based on the past performance, we actually didn’t know what the circumstance would be in the next one because the audience would change. [Turning to face Liz] You had to step out of the performance, but we had to step into an entirely new situation each time.

Michael: One could say that chase and Flight turn each other inside out. They’re complementary, like different sides of the same coin. chase proceeds from scripted scenes that are lent spontaneity by the unexpected interactions with passersby, while Flight transforms source material from films into a live theater experience that’s intensified by serendipitous interactions with an assembled audience.

Max: For Flight, and I guess for chase too, the audience directed how the scenes would play out based on how open they were to playing with us. In Flight, simply where they wanted to park themselves on the steps changed what we could or could not do or what we wanted to do or not do. The audience helped create our space.

Elizabeth: Also there was an increasing number of people coming to see Flight. I know some of my friends who came were planning to come to an early show but they enjoyed it so much that they just stayed. The audience grew bigger and bigger. That changed the whole dynamic of what was possible for us. Max, you had that funny moment where you drank something—what did you drink?

Max: I drank some guy’s beer [all laugh].

Liz: People ask about your gummy bear-snatching scene in chase too.

Max: [Lunges forward speaking in a mock whispering tone.] That’s my thing; I just eat people’s food. [Laughter. Max steps back and bends forward to stretch.]

Liz: [Pointing in the air with index finger] I think you’re onto something, for the next project we’ll go into restaurants and start eating people’s food [more laughing]. But going back to Chris’s initial question about my non-presence in Flight, did that make you as performers feel abandoned and that I was shirking the responsibility off onto you? Whereas in chase, it often felt like a duet or tag-team approach.

Nic: Well, it’s the difference between filmmaking and theater making. In filmmaking the director is going to be more of a presence, but with theater it’s part of the expectation that you’re going to step back and it’s up to us. It’s just the nature of the two things. [Starts jogging in place to keep warm.]

Michael: You approached Flight through the prism of theater and film, as well as your more established background as a visual artist…. [pauses to ponder]

Elizabeth: [steals Michael’s lines, impersonates him] I hinged my performance more on the script and the choreography than the crowd [everyone laughs]. I wasn’t out to instigate something with the audience, but did embrace those moments when they happened organically. As opposed to your palpable presence as the artist in chase, you vanished into the fabric of Flight because you really became a director and choreographer.

Lizzie: Michael you just got upstaged! [All throw heads back, roaring with laughter.]

Max: Also as a director in Flight, there was a different kind of prep work. You had provided us with a controlled or semi-controlled space. Even with the audience and circumstances in flux, there was a set time for the performance. There was a structure already built around the process. [Sirens sound as if coming from some blocks away, growing louder and closer.] With chase, there wasn’t. The difference is, as a director you had little control over our environment in chase. You did have some control in Flight. You basically said, “Go into this environment I created for you with this script.” That’s much easier to do as an actor. I also think if we are going to talk about the artist as director we also need to talk about Elephant Calf a little bit too, which was another kind of directing where we were working from a traditional play—a completely different and fascinating project. It presented [speaks louder over the sirens], presented a different slew of challenges. It was staged at a gallery exhibition opening for chase, so rather than performing solos at ATMs, for the first time we were all in the same room and had to perform together. [Shouts over the siren noise.] It was a real challenge to figure out how to get everyone on the same page in terms of acting styles [sirens overwhelm his voice].

Chris: Right on cue.

Max: [Laughing] This is the drama we were waiting for.

Nic: And now they all come to arrest you, Liz.

SCENE III: Interactive Tactics for Regulated Space

Chris: How different is it to perform with your theatrical experience in an interactive museum environment, where the audience has different expectations? Does it change what you’re doing?

Michael: [Shrugs shoulders. Touches chest, gesturing to himself] I think it’s an exhilarating collision.

Nic: When you’re separated from the audience on a stage you don’t think about them the same way you do when you’re in the middle of them. There’s the risk: I have to perform but I still have to deal with the audience [gesturing toward audience].

Max: Particularly in Flight when we got so physically close to people, the audience becomes your second scene partner at all times.

Michael: With chase [pauses and recomposes posture], and Liz, you may disagree with me here, we were doing a series of solos that then converged in the editing of the piece, and we had a wide range of approaches, which imbued the piece with a dissonant texture and an off-kilter syncopation. Max was more guerilla style. In my case we shot in less populated venues during low-traffic hours because that’s what worked logistically. This proved fortuitous in the working process as it allowed me to create a self-contained world within the script.

Liz: [Hits the script against her leg.] That made sense for your character too. He was ditched by his comrades, isolated, and finally cast out from his society. But with Lizzie for instance we decided to approach one scene in a more continuous manner at an hour when the bank was quite busy.

Lizzie: [Nods her head in agreement.] Right, I could feel the narrative arc and it became an interactive performance with bystanders, while some of the other scenes were more pieced together through the editing process.

Liz: You were this unrequited, mistreated wife or widow-to-be. It was a resonant role to come into a bar that was really a bank and say, “Where have you been? Where’s the fish you were supposed to bring home?! How could you treat me this way?!”

Max: Definitely the way you and Michael worked was very different than the way you and I worked. You and each person you were working with developed a relationship and method to working on the scenes.

Liz: For chase I made a sort of pact with each of the nine performers [helicopter sound interrupts]…

Max: Wait, no, read that line again, Liz, because I really think it’s true.

Liz: For chase I made a sort of pact with each of the nine performers. We agreed to meet a few times a week at branches of their bank. It felt like we became pioneers in our everyday space: we went in with a mission, staked out our territory and made a concerted effort to oppose how that space usually structures our behavior.

Lizzie: We made a pact with you, but there was no pact among the actors. Had we done it in a theater, as a continuous piece on stage, we would have had to make a pact with each other as actors.

Max: We would have had to agree on certain basic truths for the performance.

Chris: Did the situations with the bystanders in the banks ever feel antagonistic?

Max: Yes, I basically treated them as if they were interlopers in my space.

Liz: [Gestures emphatically.] Our focus on our initial audience in the bank was vital and our interactions with people varied wildly. There were moments when we made friends, had fun with people and exchanged info. Then there was someone who was probably a Vietnam vet, he had an Army cap on—it was with Max and this guy got upset because you were saying a line like, “Don’t you want to put on the garb of the tremendous British army?!” And then the guy called you an asshole and we think he called the authorities on us.

Max: Yeah, we got kicked out.

Liz: So we experienced the full range of reactions from people in all these different neighborhoods. We were ten different personalities, which led to a spectrum of engagements or non-engagements with people. Sometimes people trying to ignore us seemed aggressive, more of a presence than someone just giving a chuckle. But let’s return to what Nic was saying earlier about Flight marking a transition from the methods of a filmmaker to those of a stage director.

Max: And also those of a choreographer too. There was a real aspect of choreography in Flight. In some ways that was the webbing of the piece. Obviously because of your background it’s something you know about and that came naturally…

Chris: [Whispered aside to audience.] Liz’s mother is the choreographer Wendy Osserman.

Max: …There was a controlled structure at MoMA PS1, it was about creating that webbing, a choreographed webbing that allowed scenes to flow from one into another. It gave us the freedom as actors to be in a scene and do whatever we needed in order to interact with each other and with the people who were in our way if the opportunity presented itself.

Liz: We became so focused on the transitions from one scene into the next, it really became about the transformation of your roles. You were always in flux between victim and aggressor; relationships were constantly shifting.

Nic: We had to be careful about detracting from someone else’s scene. We’d have to transition but someone else had a scene going on and we couldn’t disrupt the scene that was unfolding.

Lia: [Gestures emphatically with her arms.] The choreography and blocking really informed each scene in a different way. In theater that always comes second, as backdrop to the interaction. The interaction became so physical, particularly the fighting, that a sort of momentum and need to get through people to be in place at a certain time heightened the psychological action as well. It brought out the fear in the scenes and the close links between those two things. They fed off each other.

Liz: Which two things?

Lia: Acting and choreography.

Nic: It was all about doing.

[Lizzie and Max rhythmically step back and forth from the circle for the next five minutes.]

Michael: [Drops pen, bends down to pick it up, and proceeds to gesticulate with it.] The legacy of various recent art traditions in New York is an apt reference point. There’s an element of guerilla theater—and its nascent manifestation via interactive provocation in the ‘60s with Living Theater, and also there’s the mimetic quality of Flight, echoing what the Wooster Group pioneered, channeling something recorded through the medium of live theater. Connectedly, this is a product of the convergence of these forms of theater and the transformation of the notion of public space in New York, through gentrification in the last few decades; and the parasitic relationship between the monetizing of information and the overarching culture of surveillance.

[Two joggers enter in the background, passing from stage left to stage right.]

Liz: This is something that Douglas Crimp writes about, how in the ‘70s the urban crisis and subsequent transformation of downtown New York from a manufacturing center into a financial center created an upheaval that allowed vacant warehouse space and outdoor space to be available for artists to work in. [Points toward stage left.] It seemed to be a utopian moment, but it was made possible by the crisis that was happening. It was really just a blip, which allowed for this fertile ground in conceptual performance to occur in urban space.

Max: It’s the act of transition that allowed for dynamic creativity. I think it’s been happening the last few years too.

Liz: I think we are going through a moment when we’re trying to reclaim that. It’s almost as if it was our fault that this moment died down, but it wasn’t our fault exactly. It was that economic and social conditions were changing rapidly.

Chris: And perhaps chase touches on this sense of guilt or anxiety while folding in the realities of a finance and service-based economy.

Liz: In a way, yes, we were being playfully threatening toward people in these bank vestibules, toward this everyday complicit behavior, but the underbelly of it was all about fear.

Lia: I think it’s really important that chase took place in New York. If it were not in New York it would resonate in a different way. To fight for personal space or have an illusion of personal space becomes very important here. In Flight, the action of fighting through people and moving through people is like going through Times Square or getting on the subway at 5pm.

Liz: And now we will take Flight to Times Square! [All cheer.] The very heart of the urban crowd, not to mention the Broadway Theater…

[Max raises both arms and everyone cheers.]

Michael: [Singing] Right back where we started from…

[Michael mechanically wriggles his body as if his feet are stuck to the stage, then frees up his feet and begins to dance. Everyone catches the rhythm.]

Liz: But this issue of invading personal space is central. In the bank vestibule there was a strict code of privacy; we were transgressing an understood social code, and then with Flight we brought that intention into an art space. At PS1 we were dealing with an initiated audience so we tried to amplify the interactions with people and transgress the audience’s space. Where we are… sitting now in the… bleachers is usually the safe space [affects confusion about discrepancy]. There is typically a clear-cut barrier between audience and actor so you don’t have to worry about the action intruding on your personal space; your potential to act and take responsibility is foreclosed. Flight was about crossing that physical boundary and opening the floodgate of responsibility.

Max: [Pointing back and forth with script.] I think that goes for both sides too, so as an audience member the actors don’t interfere with you and simultaneously for an actor on stage you’re protected from the audience.

Liz: There’s a sort of barricade.

Lizzie: Like there’s a moat right here [pointing toward the precipice of the stage. All eyes follow her finger.].

SCENE IV: Reconfiguring Fear

[Fed up with the cold shade, the group shifts upstage beyond the concrete proscenium arch. Center stage lights come up, simulating brighter sunlight.]

Max: With Flight, by the end of that day when people had seen the performance a couple of times, they would congregate in specific areas. I think they agreed to participate by sitting on the steps. They said, “We’re here. We agree to play with you” to whatever extent they were going to play. In chase we didn’t ask their permission at all. They happened to be there and their participation was accidental.

Elizabeth: The audience started intruding on our space too. They started getting involved in a way I wasn’t expecting. One lady tried to come to my rescue at one point. She tried to pull Michael off of me.

Michael: I don’t blame her…

Max: A lot of people did decide to go along with the scenes rather than inhibit them. In 28 Days Later there was that guy who came running up the stairs with us.

Lia: [Lia jumps into the center of the circle, bending her knees and rocking her hips back and forth.] At one point in the last scene I was supposed to fall down and someone stopped my fall. As a character I was thankful to be saved—that’s awesome—but as a performer I had a responsibility, a commitment to uphold, to continue to the end—to death—it was a weird place to be. In general, it’s like the way people react to movies, or at least how I react to movies [shouts and claps hands rhythmically], “No, no, no! Don’t go there!” The audience was given an opportunity to interact with film in a way you usually can’t. [Kicks up right leg and then bends down to touch her toes.]

Liz: The audience is usually rendered helpless, but in this case they could help.

Max: One of the fun things about Flight and chase was that it allowed us to put ourselves in harm’s way in a safe kind of way. To allow yourself to be a disruption is hard. In real life it’s very hard. You see someone get robbed on the subway [assuming a mock menacing posture] and you think, “Whatever, it’s not my business” [steps back striking a defensive pose.] And five minutes later it dawns on you that by being a passive bystander [points to audience] you’re part of the problem, so it’s not whatever! You can’t just idly sit by and watch things happen and pretend that you’re not responsible. These projects have allowed us to be that disruption, to interrupt the flow of people taking out money or sitting on the stairs. [Nic leans his elbow on Max’s slumped shoulder.]

Liz: This plays on how the spectator-performer scenario relates to our everyday life. I’m interested in looking at how fear guides decision-making. I’m not saying that you should always put yourself in harm’s way, but it is worth looking at how we keep ourselves in place and how out of fear we often don’t interfere. We self-impose this paralysis, and the political ramifications are real.

Elizabeth: I loved working with the fight choreographer [Miranda Hennum], on Flight. The first thing she instilled in the Scream scene I had with Nic was to make sure we made eye-contact. This goes back to what Lia was saying about fighting for personal space in the city. You’re basically competing with others on the street and the last thing you want to do is make eye contact with them or with anybody who presents a threat.

SCENE V: TRANSGRESIVE TRANSACTIONS

[A vague electric vehicle sound seeps in. A cyclist enters in front of stage right, circles to survey the scene, loops back around, and exits stage right.]

Chris: Can these actions in ATM vestibules be read as an act of protest?

Michael: I think so. We are relentlessly, subliminally being spoon-fed the message that we are secure to feel insecure. Liz’s work is a provocation that draws attention to this phenomenon, while at the same time providing a wry, self-aware, running commentary, an erudite play-by-play… wait a minute [dissatisfied expression].

Chris: [To Michael] Do you want to strike that last sentence?

Liz: We didn’t edit that one, so it’s what you said.

Michael: [Gesticulates dramatically.] I think I said more though, so it’s not clear what it means when it’s truncated.

Liz: So say more now.

Michael: Okay, in other words, we are constantly bombarded with these intrusive messages in public space. The suggestion is, we’ll protect you, but be duly advised that if you transgress, you’re stepping into the line of fire, you’re vulnerable. There are persistent reminders, along the lines of the chillingly Stasi-esque message we hear intoned clear as a bell over the normally inscrutable loudspeaker during our commute, “If you see something say something.”

Liz: What we’re doing does have an element of agitprop.

Max: It certainly can be subversive, but there’s something playful about it too; there’s a wink and nod because we would use our own cards and utilize the bank when we’re in there. So if you are to call it protest, then I think it’s a very specific kind of protest that operates from within the system and not from outside. Because it’s not like we completely negated what a bank is supposed to be used for. If we were doing a scene in the bank and wanted to go to lunch, then we’d take out money from this same bank. To a certain extent we operated within the bounds and rules the bank set up. We didn’t negate the usefulness of the bank or the power of the ATM.

Liz: And some earlier interventions actually preceded chase, such as a performance in which I deposited prosciutto in the ATM. It was just an experiment. I inserted the prosciutto, it disabled the machine and it must have been caught on the surveillance camera. In the back of my mind I was vaguely expecting a fine would arrive in the mail every time I opened a Chase envelope, but the fine never came. It showed me that the space is not quite as controlled as I thought. These cameras are put in place to threaten us with repercussions, but enforcement is probably not worth it for them unless someone steals a large amount of money. So many of our daily interactions with the world are with machines. You go to this place with an ATM and you…

Chris: …feed it some prosciutto. And like this simple gesture, chase takes abstract ideas of capital and finance and renders it in a much more corporeal, physical way.

Liz: Yes, our daily interactions have become daily transactions.

Max: Ain’t that true. Even with people, how many interactions do I have in a day in which nothing is being shared? They are totally transactional relationships with human beings. And then it’s funny in chase to have non-transactional relationships with machines. The machines stood in for people.

Chris: So much of urban life is about humans becoming automated. We didn’t get onto a 24-hour clock until we were living in urban environments. You become mechanized.

Nic: [Thrusts his fist forward] It always shocks me when I’m at my job as a server and people ask me how I’m doing. I always ask people how they are, but when they ask, “How are you?” I go, “I’m good. Thank you for recognizing that I am not a machine.”

Michael: They crossed the fourth wall.

Liz: [Throws out upturned palm] “You recognize me!” That’s a big one. I’ve been thinking about the desire to be recognized by the machine. They say ATMs will soon have face-recognition software.

Nic: At a Chase bank I remember the ATM had a very colloquial way of saying it was out of receipts. It said, “I’m so sorry, Nic, but we’re out of receipts, is that okay?” and I went, “Oh, it’s okay.” It made it seem so personal.

Liz: There was a time a few years ago when I accidentally said thank you to an ATM. That was one of the events that precipitated the chase project. I realized how unconscious we get in that scenario, how basically you walk in, glaze over and become this drooling automaton for a moment. I don’t remember being in the bank at all until I malfunctioned and said, “Thank you.”

[Chris grabs microphone. All roll up their scripts and exit stage right. Lights fade out.]

About the Cast

Liz Magic Laser (Director) is an artist and teacher born and raised in New York City. A graduate of The Whitney Museum Independent Study Program and Columbia University’s MFA program, Laser’s work has been shown at the Prague Biennale 4 (Czech Republic) and Greater New York 2010 at MoMA PS1. She is currently creating a project for the Performa Biennale, 2011.

Christopher Y. Lew (Producer) is Assistant Curator at MoMA PS1. He organized the first presentation of Flight on MoMA PS1’s courtyard staircase.

Nic Grelli (Actor, Flight) graduated from NYU/Tisch’s Experimental Theatre Wing and has also studied acting for years with acclaimed teacher Maggie Flanigan. Nic has worked with Berkeley Rep, PS122, EST, The Longest Lunch, MariaColaco Dance, WTE Theatre, Purple Rep, The Dramatists Guild, extensively with Labyrinth Theatre Co, and on a number of webseries and short films. Nic is also a playwright, screenwriter, and dancer.

Elizabeth Hodur (Actor, Flight) has worked extensively with modern dance company SITU (Untitled Cities, Thunderstorm, Behind the Cathedral, Ha!). Additional stage credits: The Girl Show, Reality Bytes, Fast Forward Flash Back, The Lovely Leave (theater and film), Directory Assistance, The Heidi Chronicles.

Liz (Lizzie) Micek (Actor, Flight and chase) is a film, theater, and voice-over actress. She trained at the William Esper Studio in New York City. In addition to many memorable collaborations with Liz Magic Laser, Lizzie has also appeared in several indie features, most recently Freeloader directed by Zach Raines.

Mia Tramz (Photographer, Flight and InterAct) is a recent Columbia University alumna. She photographs in NYC and the surrounding areas.

Michael Wiener (Actor, Flight and chase) is a film and theater actor, performer, and writer. Recent work as an actor includes the international film festival hits Stingray Sam and The Way I See Things, and Tennessee Sheen, a deconstruction of Tennessee Williams’s Night of the Iguana, presented as part of Little Theater at Dixon Place. An autobiographical essay will be published by Seven Story Books in an anthology of writings by Lower East Side Jewish cultural practitioners.

Lia Woertendyke (Actor, Flight) is an interdisciplinary artist and arts organizer. She is currently finishing up her BFA at Pace University where she is very active in both the theater and fine arts departments directing plays, curating exhibitions, and exhibiting in group shows. Lia is also the gallery director at culturefix bar and gallery, where she curates multidisciplinary exhibitions and events.

Max Woertendyke (Actor, Flight and chase) was born and bred in Brooklyn and has been seen on stage at The Public, Cherry Lane, PS 122, Theater for the New City, and others. He has also worked on numerous films including the recent indie feature Beneath the Rock premiering at the SoHo International Film Fest. He will be attending the Juilliard School of Drama in the fall.

The performance work for both chase and Elephant Calf was developed in collaboration with actors Annika Boras, Andra Eggleston, Gary Lai, Liz Micek, Justin Sayre, Doug Walter, Michael Wiener, Max Woertendyke, and Cat Yezbak. Set and costumes for Elephant Calf were done in collaboration with Felicia Garcia-Rivera and included production coordination by Mia Tramz. A playbill booklet was designed by Lauren Adolfsen and includes texts by Carmen Dell’Orefice, Lucy Gallun, Jordan Troeller, Tom Williams, Alberto Pepe Gentile, and Spencer Wolff.