From Art Journal 79, no. 4 (Winter 2020)

In March 2017, controversy erupted over white American artist Dana Schutz’s contribution to that year’s biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Her painting, Open Casket, renders in oil the disfigured, brutalized face and torso of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old African American boy who was lynched in Money, Mississippi, in August 1955, for allegedly whistling at Carolyn Bryant, a white woman. Bryant recanted her story in a 2008 interview that was made public in January 2017, six decades after Till’s murder.1 Schutz’s source material included postmortem photographs of Till’s remains, which were reproduced, at the behest of his mother, Mamie Till (later Till-Mobley), in the popular African American picture magazine Jet; African American newspapers the Chicago Defender, the New York Amsterdam News, and the Pittsburgh Courier; and the Crisis, the NAACP’s organ. Rather than keep her grief hidden, Mamie Till invited the world to see what the southern racial and sexual caste system had done to her son. The photographs were greeted by a culture not only willing but desiring to look, particularly because in 1955 the visual evidence of lynching by way of the photograph was largely out of sight, extant but kept hidden. Mamie Till’s marshaling of the force and fury of her son’s murder would serve as a catalyst for the modern civil rights movement.

But 2017 is not 1955. And Dana Schutz is not Mamie Till-Mobley. Audiences, Black audiences especially, have been inundated with a seemingly endless loop of images of Black death at the hands of law enforcement and vigilantes, via Twitter and other platforms, on computers and cell phones. The ready availability of Black death, always only a click or two away, is what art critic Teju Cole has lamented as “Death in the Browser Tab.”2 Within days of the Whitney Biennial’s opening, more than one hundred Black artists and art professionals signed onto a letter denouncing Schutz’s painting and the biennial’s organizers, curators Mia Locks and Christopher Y. Lew, both Asian American.3 The protesters claimed the painting, by a white woman and displayed in a historically white and exclusionary venue, served only to spectacularize Black death, and they called for the painting to be both removed and destroyed. “In brief,” the letter stated, “the painting should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about Black people because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time. . . . The painting must go.”4 Members of the group staged daily protests, standing in front of the painting in order to block it from the view of other visitors. In the months that followed, a flood of artists, art historians, curators, and other cultural figures, from Locks and Lew to Coco Fusco to Whoopi Goldberg, voiced their opinions about the display of Schutz’s painting and the protest it engendered, “form[ing] a constellation of disagreements.”5

As a scholar of photography, social movements, and Black diaspora, I was unfamiliar with Schutz’s work until the protest movement brought it to my attention. Alerted to the controversy in this manner, I engaged with Open Casket—like so many of the artists and activists who organized to protest the painting—through the expansive field of visual culture, or what Nicholas Mirzoeff calls a “critical visuality,” rather than the more traditional disciplines of art history and curatorial practice.6 At the intersection of race and visual culture in which I work, alongside other scholars such as Tina Campt, Courtney R. Baker, Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, Shawn Michelle Smith, and the late Maurice Berger, we must consider the ethics of seeing and viewing Black death in our contemporary moment. When does visual representation of Black death become a spectacle for uncritical or merely aesthetic consumption and when does it serve efforts toward justice? What are “appropriate” forms of artistic commemoration of Black lives like Emmett Till’s, ended prematurely by state-sanctioned violence? Who has a right to which memories?

It has long been my contention that memory and memorialization are necessary to projects of political mobilization and redemption and provide a pathway to justice through honest acknowledgment of one’s history—our shared history—in all its beauty and terribleness. In the hands of Black artists and scholars—myself included—photography’s work has been memorial and redemptive. Indeed, my own formulation of “critical black memory,” as found in art and photography, especially the photography of African American freedom struggles, is “a mode of historical interpretation and political critique that has functioned as an important resource for framing and mobilizing African American social and political identities and movements.” I still very much believe in the role of art and photography in critical black memory as offering “a space to organize for the future while making critical assessment of the past.”7

We can consider here the archive of lynching photographs that Schutz engages, however clumsily. Originally produced as testimonies of white supremacy, lynching photographs soon were employed by African Americans in the emergent antilynching movement. Beginning with the pioneering work of activist Ida B. Wells, the first to employ lynching photographs, in her 1893 essay “Lynch Law” and her 1895 pamphlet A Red Record,8 these images appeared in antilynching propaganda and pamphlets of the NAACP and other antilynching organizations, as well as in reports of white mob violence in the Black press. In such contexts, these images transformed the dominant narrative of Black savagery into one of Black vulnerability; white victimization was recast as white terrorism. Though not the producers of lynching photographs, African Americans were nonetheless implicated as objects and spectators, and as such, many chose to respond through appropriating and recontextualizing these images.

For civil rights and Black Power activists, lynching provided a key referent for the continued terror experienced by African Americans, whether in the rural South or the urban enclaves of the North and West. Organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panther Party made use of lynching photography in their newspapers, pamphlets, and posters. And since the formal end of Jim Crow, subsequent African American artists and other artists of color, including Public Enemy, Renee Cox, Hank Willis Thomas, Dread Scott, Pat Ward Williams, Kerry James Marshall, Alexandra Bell, and Ken Gonzales-Day, have returned to these images as a way to repair, redress, and mourn and as a call to action. They have repurposed lynching photographs as critiques of contemporary crises and to draw explicit connections between the end of slavery and the age of Obama, in which the relationship between racial violence and Black citizenship remains an unsettled and unsettling one.

A common feature of these works is the centrality of the Black body; even when muted (Marshall), annotated (Williams), redacted (Bell), or erased (Gonzales-Day), the brutalized body of the lynched remains an absent referent. All this work, from Ida B. Wells to Kerry James Marshall, has fundamentally been a call to a critique of white supremacy. And it has sounded this call through presenting the brutalized Black body as evidence of white supremacy’s violent hypocrisies. That is to say, this is visual work that has aimed to challenge a system of racial oppression while simultaneously asserting the humanity of Black peoples. And indeed, the debates around Open Casket seemed to hinge not merely on the choice of subject matter—the image of a lynched Black boy painted by an adult white woman—but on Schutz’s aesthetic choices as well, specifically her mobilization of the tension between painterly abstraction and figuration. As some argued, the figuration of a face disfigured by violence in a sense abstracted Emmett Till’s murder, and thus Schutz’s work failed precisely because it tried to address white complicity with Black death without attending to the value of Black life.9 In arguing so, these artists and activists have relied on the figure of Blackness, the visual representation of the human.

I want to consider here that perhaps a means of simultaneously asserting Black humanity and critiquing white supremacy is not through the figural or visualizing of the vaunted yet contested category of “the human.” Most basically, the task of visualizing human rights has necessarily entailed visualizing the human. That is, recognizing that those subjects pictured within the photographic frame or on the artistic canvas fit within the often taken for granted, yet unevenly applied, category of “the human.” Caribbean philosopher Sylvia Wynter has argued that not only has Blackness stood outside of the category of human, but also the human as an enlightenment concept is fundamentally formed in opposition to Blackness. As such, the “(Western bourgeois) conception of the human, Man, overrepresents itself as if it were the human itself.”10 For Wynter, our species’ survival depends on rethinking our origin stories, undoing “systems of racial violence and their attendant knowledge systems that produce racial violence as ‘commonsense,’” and retraining what she calls the “inner eyes” that shape how we perceive reality and dehumanize others.11

To retrain our inner eyes, we must revisit the visual structures that disciplined our sight initially. Perhaps the way to commemorate the dead and move toward a more just vision is through the genre of abstraction. “Abstraction,” in its most fundamental definition, means a state of withdrawal from some original point. I propose that abstract art that specifically moves away from figuration potentially offers a means of challenging white supremacy. And I emphasize nonfigurative in part to distinguish from the abstracted but still vaguely figurative work of Schutz’s Open Casket, which returns us to and depends upon the visual presence of the Black body (and the images that cathect around it) without offering a critical reading of systemic racist violence. The controversy around Open Casket brought into sharp relief the ways in which the representational regimes of fine art collide and collude with quotidian representations of Black living and dying. My project here is not to argue for or against the formal merits of Schutz’s painting or her personal racial politics. I wish to start not from her canvas and its “artistic intentions” but rather from the collective organization behind the protests, and to take this public controversy as a demand to think critically about abstraction, figuration, and the representation of Black death that, to borrow from the writing of Christina Sharpe, aspires toward an ethics of seeing and of care and that insists on Black survival (and more).12

Here I will focus on the assemblage work of African American artist Samuel Levi Jones and the video work of white American data artist Josh Begley, each of whom creates art in memoriam to victims of police brutality that turns viewers’ attention away from Black bodies and the burdens of representation those bodies are made to bear. Instead, Begley and Jones redirect us toward the systems of power that produce Blackness as fungible commodity and Black life as expendable. Through different though “classic” forms of abstraction—Jones’s employment of the grid and Begley’s use of the map, specifically the technology of Google Maps—each challenges the ways we are disciplined to “see like a state.” And by seeing like a state, I am referring to anthropologist James C. Scott’s study in which he identifies the ways states work to simplify and make their societies legible through “remarkably visual aesthetic terms”: the creation of the “standard grid” through which complex bureaucratic and other functions can be “monitored and recorded” or the ways in which maps or orderly and controlled systems “that when allied with state power would enable much of the reality they depicted to be remade.”13

Blackness and Abstraction

Let me offer two distinct but interrelated ways that I am thinking about abstraction in relation to the representation of Black life: first as a specifically aesthetic problematic and second as a legal and theoretical category—that is, the concept of abstract personhood.

The longue durée of Black representation has often been cast as one of ongoing and uninterrupted struggle, a now hidden, now open fight between abjected Black subjects, banished to the margins of affirming representational forms (like portraiture) or iconized as ludicrous or louche, vile or villainous.14 In this history, Black peoples have invested in the “positive image”—the True, the Good, the Beautiful—as a means of gaining social equity and recognition as well as reprieve from the prison house of representation. In the realm of the visual, all that was required were successful images that defeated a seemingly endless march of images of failed Blackness. Black representation is understood, then, as doing specifically political work, uplift work. And thus figuration—in the form of portraiture or sculpture, for example—has been central to this sort of representational project, what Stuart Hall called the “relations of representation.”15

Following the denouement of the social movements of the 1960s, the rise of multiculturalism opened up spaces for new and multivalent expressions of Black identity that would have great import for Black representation. Hall famously announced “the end of the innocent notion of the essential Black subject,” in which we witnessed a shift away from “a struggle over the relations of representation,” defined by countering Black invisibility and exclusion with mere presence, replacing derogatory images with “positive” ones; and a move toward “a politics of representation itself” that must contend with the increasing hypervisibility of Black bodies, that challenges not merely the fear and loathing of Black subjects but their fetishization as well, and that seeks to read Blackness as a series of signs rather than as essence.16 Hall recognized an awakening away from an ardent faith in the singularly defined Black representation that would challenge and overthrow a sordid and oppressive history of media marginalization.

Black artists and cultural producers have offered a multitude of challenges to the failures of Black representation. During the mid-twentieth century, at the height of Abstract Expressionism, a number of Black artists engaged in a range of nonrepresentational practices. The abstractionist paintings of Norman Lewis and Frank Bowling, the sculptural works of Fred Eversley and Tom Lloyd, the collages of Romare Bearden and Howardena Pindell—each offered images of Black life and feeling without recourse to the figurative. In the era of multiculturalism, some artists openly rejected the strictures and structures of traditional representation: for example, the “anti-portrait” as presented in the work of conceptual artist Glenn Ligon or the refused gaze at work in Lorna Simpson’s oeuvre. But the pull has largely been to the redemptive and oppositional image, as in the work of Betye Saar or Carrie Mae Weems.

Another route has been fantasy and fabulism—modes that highlight the fictions that undergird our concepts of race in the very first instance. Put another way, if Blackness is itself an imago, a fantasy woven out of the anecdotes and stories, fears and desires of a dominant society, then perhaps the best way to represent that Blackness is not through a turn toward verisimilitude. Rather, one might consider those excessive performances—camp, science fiction, Afrofuturism—that represent Blackness not as a true likeness but as an always already invention, Blackness not as a finite answer but as an endless series of questions.

Abstract art, especially mid-twentieth-century Abstract Expressionism, was celebrated by critics as art in its purest form, unencumbered by the burdens of the figurative, freed from political distractions, and divorced from socialhistorical context—that is, separate from the world beyond the gallery. While art critics, theorists, and historians have since pushed back against this sort of high formalism—we might think here especially of work by Kobena Mercer, Adrienne Edwards, Okwui Enwezor, Chika Okeke-Agulu, Mary Schmidt Campbell, Stephen M. Best, and others—Black art as confined to the policed boundaries of “Black representational space,” to borrow Darby English’s term, is not always afforded such leeway.17 As these scholars have shown us through careful studies of Black artists overlooked and/or excluded from the abstractionist canon, abstract works made by Black artists place pressure on the desired stability of “Black Art” as a category.18 Even further, these works destabilize the notion of certitude attached to visualizing racial Blackness: What is it that (we think) we actually see or know about Blackness when looking at a nonfigural work of “Black Art”?

If abstract art (including its many historical subfields like Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, Conceptualism, and so on) has been a genre from which Black artists have been excluded or at least marginalized, this is at least in some part tethered to the notion of abstract personhood, in which whiteness is considered universal and all others racialized, specific, particular.19 Here, we must consider the concept of “abstract personhood” that forms the basis of US law and functions as law’s ideal subject. From the moment of the nation’s founding, that subject was understood as white landowning men. Subsequently, this subject served as the basis for assessing human value and worth.

Yet, simultaneously, abstract personhood has been marshaled against Black persons, “annulling their humanity,” dehumanizing and “thingifying” them in such a way as to render them as a general category suitable for enslavement, while underscoring a national personhood elevated to the universal from which Black people are for the most part excluded. Cultural theorist Phillip Brian Harper writes, “Social-politically . . . by the late eighteenth century abstraction constituted the cognitive mechanism by which persons of African descent were conceived as enslaveable entities and commodity objects, and yet paradoxically denied the condition of disinterested personhood on which U.S.-governmental recognition has been based.”20 Blackness in its visualizable specificity itself becomes an abstraction, a removal away from “the human.”

Such abstraction also extends to the violence enacted through the technologies by which the state orders itself and its subjects. Both maps and grids function to impose order and structure, whether on unruly systems or the vast “apparently limitless space of the known world.”21 Maps and grids then are often records of power and domination; they are projections of belonging and subjection. And when such technologies announce themselves so seemingly unequivocally, we know they are hiding something. “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism,” wrote Walter Benjamin. “And just as such a document is not free of barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another.”22 Maps and grids also invoke the limits of knowledge and the failures of sight (following Anne McClintock), the perils of margins and thresholds in a world of terrifying ambiguities, whether it is a “dark” continent, a wild frontier, or an as yet ungentrified neighborhood.23

Ultimately, the question that drives this inquiry is how to represent white supremacy? How to see it, name it, indict it; to call it to light and call it to task? And how to do so in a way that does not rely on empathy, the limits, the dangers of which Saidiya V. Hartman has so powerfully articulated for us? As an explanation for her choice of Emmett Till as subject, Schutz averred, “I don’t know what it is like to be black in America but I do know what it is like to be a mother. My engagement with this image was through empathy with his mother.”24 Hartman rejects the ways such a gesture of empathy, “the endeavor to bring pain close . . . does so at the risk of fixing and naturalizing this condition of pained embodiment,” rather than focusing on the conditions that produce, “fix and naturalize” Black suffering.25

To turn to abstraction, for me, then, is to turn to the problem of whiteness, to the structures of power that delimit Black possibility, that at once predict and preordain premature Black death. To turn to abstraction is not a replacement for the figural or a means of avoiding embodiment, especially the pleasures and dangers of Black embodiment. Abstraction is an incredibly capacious category that can mean and do many things. Rather, I am searching for a means to challenge the structures of white supremacy that, following Tina Campt, does not force us as Black people to manage our emotional responses to the frequencies and precarity of Black life,26 that does not make mourning the work of Black people alone, that does not eclipse anger while only foregrounding and replaying our grief. More than this, I am seeking a critical visuality that offers respite and reprieve from the demand to publicly perform such grief and mourning as an acceptable path to citizenship and recognition of humanity. Or, to paraphrase artist and theorist Torkwase Dyson, this project is one of surviving abstraction through abstraction.27

Burning All Illusion: Samuel Levi Jones

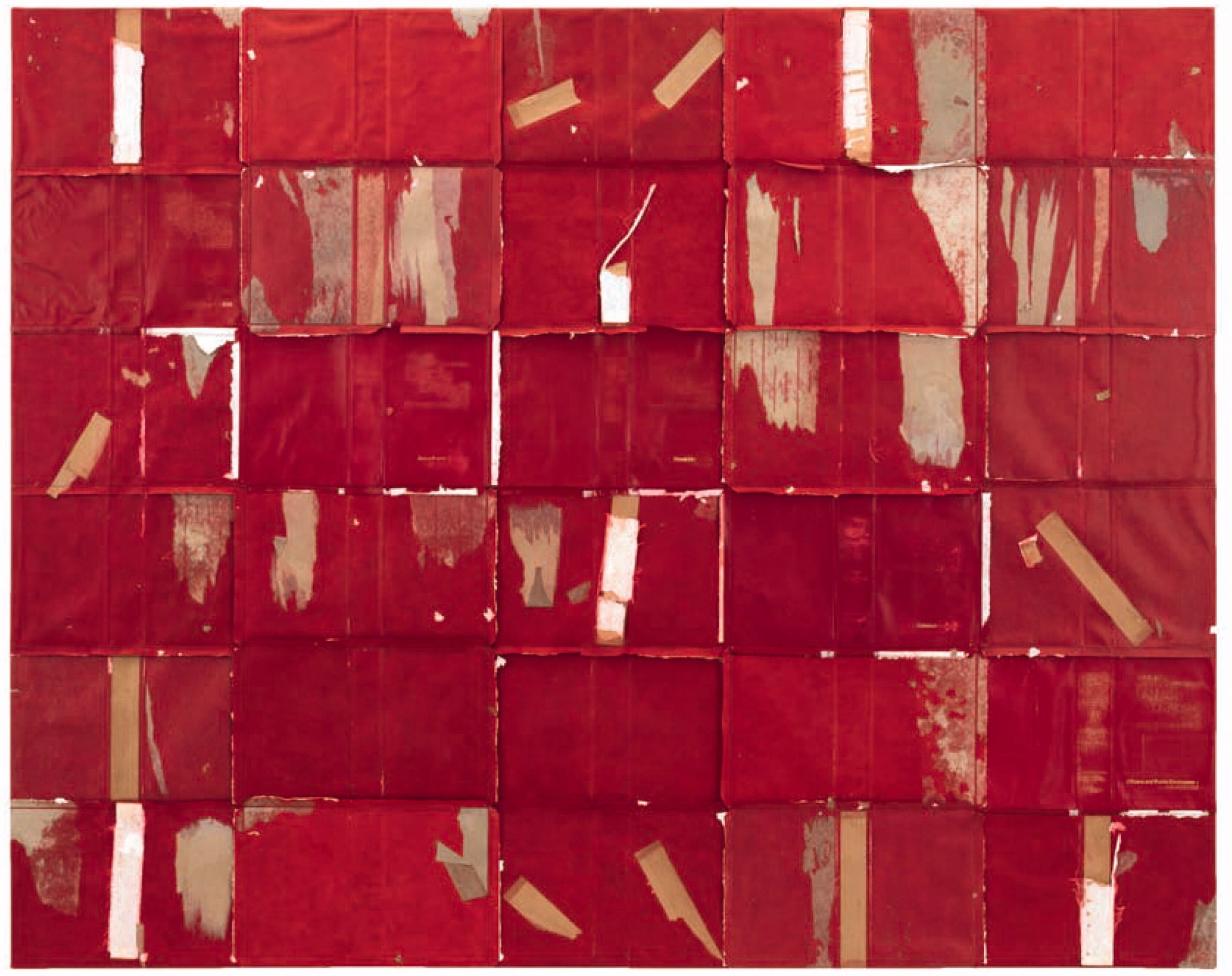

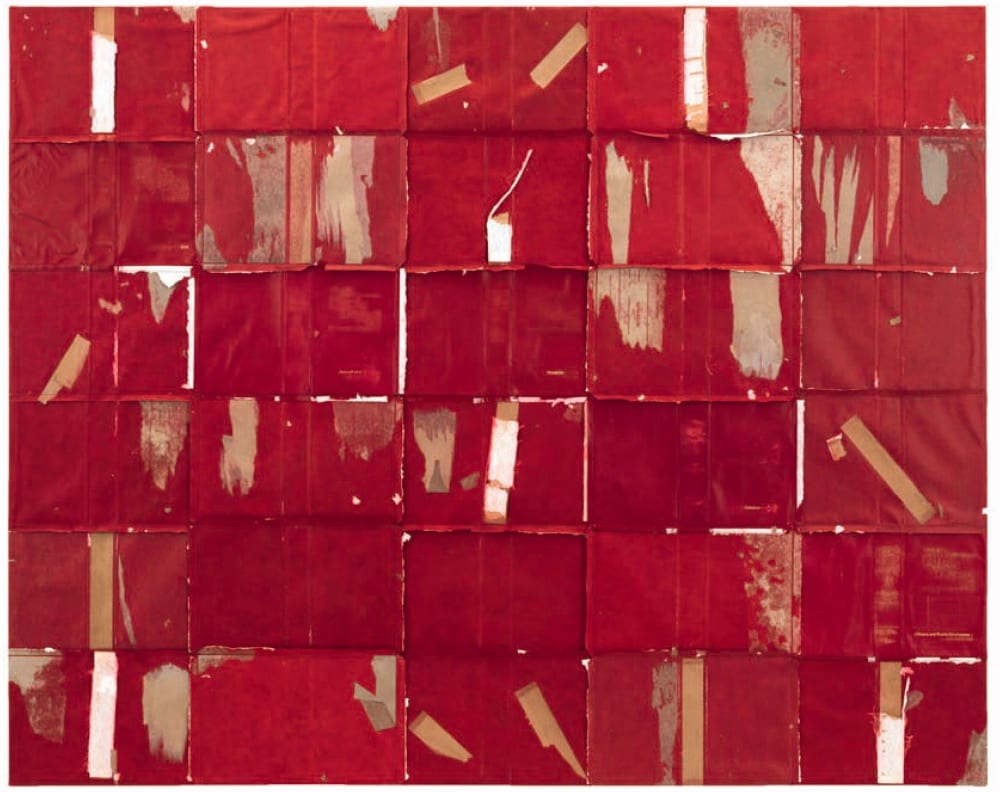

Samuel Levi Jones has variously described himself as a photographer, an activist, a desecrater, and a multidisciplinary artist. His current practice involves the destruction of historical source materials and then manipulating, stitching, and reimagining them as large-scale abstract design. Jones’s solo exhibition Burning All Illusion ran at Galerie Lelong in New York from December 8, 2016, to January 28, 2017. The show consisted of a dozen works ranging in scale from 38½ x 43 inches (98 x 102 cm) to the massive Talk to Me (2015), comprising thirty-three panels, each 41 x 38 inches (104 by 96.5 cm).

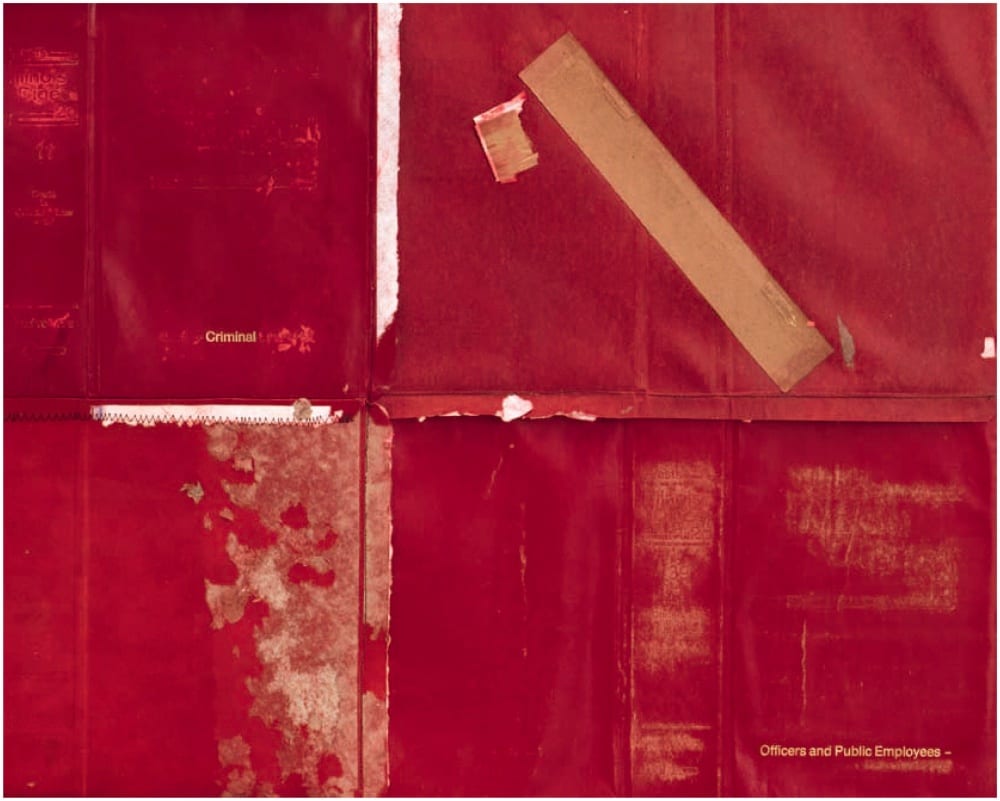

Jones’s process is at once destructive and meditative. First, Jones disassembles the encyclopedias, law books, and other reference materials by removing the covers with an X-Acto knife and separating out the pages within. Also removed are the thin layers of cardboard that give the covers their firm unyielding body. The covers are soaked in water to soften them.28 The books are torn apart, leaving the heavy cloth covers and their versos worn, scarred, exposed. Jones then assembles these covers, which he refers to as “skins,” into grids, arranging them first onto canvas before stitching them together into mostly monochromatic works via sewing machine. This latter part is particularly time-consuming and results in physically substantive and deeply contemplative works, in which there is uniformity but clear distinction: each panel reveals where it was handled, where it was broken, and where it was put back together.

Critics have described Jones’s process as “muscular”29 and even “violent,” in that it rips the books apart with strength and force. And indeed, these thickbound hardcover volumes can be disassembled only with force. They are not so easily undone.

The work is an act of destruction and also of transubstantiation, because in their unmaking as books they are remade into grids—three-dimensional handheld objects transformed into sprawling two-dimensional display. In Talk to Me, for example, the law books resemble different skin tones, and one might draw parallels to Byron Kim’s Synecdoche (1991–present). Jones seeks to understand how knowledge is produced and entrenched. He takes the vessels in which knowledge is housed—by which I mean sheltered, protected, walled off, entombed, and rendered unimpeachable—then dismantles them, exposing them, unmaking them. The racial foundations of US law, when laid bare in this way, reveal all of its colored and scarred parts. Knowledge and history, unbound and restitched, suggest beauty without hiding the wounds.

Talk to Me is a somewhat more hopeful work, one the artist has described as an open invitation to a conversation about race and history. Jones had been explicitly political since the start of his career more than a decade earlier and across his practice in photography, sculpture, video, and installation. But it was a harrowing police encounter that prompted a more unequivocal turn, as Jones began creating the canvases that make up the bulk of Burning All Illusion. Justice for Few was named right after Jones, while driving, was cut off and then pulled over by an off-duty out-of-uniform police officer when he was living and working in Chicago. Though Jones was a longtime activist and also the great-nephew of Abram Smith—one of the victims of the 1930 Marion, Indiana, lynching made iconic in the Lawrence Beitler photograph—this encounter signaled a new direction in his work.

First, Jones began to name his works more pointedly. Titles like Expendable, Gauging Vulnerability, Justice for Few, and Selective Proof of Facts make clear the artist’s commentary on the unequal application of the law. These titles gesture to the notion that some lives are more worthy of protection, more worthy of the rights and privileges afforded to citizens, than others. Law, with its attendant concepts of truth and right that undergird it, is not neutral.

Take for example the death of Joshua Beal, an Indiana man fatally shot by off-duty police officers as he was attending the funeral of his cousin in Chicago in November 2016. In a situation not unlike Jones’s own encounter, Beal’s sister’s car was cut off by an off-duty police officer. Beal got out of his own car, both to check on his sister and confront the perpetrators. In what witnesses describe as a chaotic scene, a fight ensued, and Beal was slain by eleven police bullets.30

In 2016, the murder count in Chicago was the city’s highest ever, 762, a 50 percent increase over 2015. We have to ask: What role does the state play in creating conditions that lead to such outrageous numbers? What is the role of the state in the death of Malissa Williams, who along with her boyfriend, Timothy Russell, died in 2012 in a hail of 137 bullets fired by Cleveland police officer Michael Brelo, who was ultimately acquitted? What of Tarika Wilson, who was shot in Lima, Ohio, in 2008, while holding her fourteen-month-old son, by authorities who raided her home to arrest her boyfriend on drug charges? What of the funeral that ends in a police shooting death?

In the images of broken Black bodies, it is very easy to see like a state: to question what the victims “did” to end up like this, to take a forensic inventory, to accumulate evidence. This is the process that is produced by and within Jones’s source law books: how to identify and prosecute homicide, assault, criminality.

As Black feminist geographer Katherine McKittrick has averred, the enumeration of Black death does not actually bring us to an understanding of Black lives.31 Indeed, enumeration is a form of evidence that is itself a mode of abstraction. And we might understand the grid as doing this work of enumeration without redress. The grid becomes “a way of abrogating the claims of natural objects to have an order particular to themselves,” as art historian Rosalind Krauss has written; or we might understand that the grid “assimilates and thus literally cancels the figure, in an instance of . . . ‘annihilation,’” as Phillip Brian Harper has written. Or we may think that the grid is itself an aspiration to the Universal that necessarily turns its back on the concrete.32

In a 2015 interview, Jones’s mentor, the African American abstractionist Mark Bradford, asked Jones, “If the modernist grid declares the autonomy of art, do you see your work in any way removing its source material from the social realm?” Jones replied, “For the most part, the shape of the material lends itself to a grid format. In some of the most recent work I have broken the material down further to get away from the grid a little. These works that do not fall into a grid format are simply about pushing the work visually.”33 Jones’s response can be pushed further in that his work reminds us that the source material is always already of the social realm and will make itself known.

But in naming grids Joshua, Malissa, and Tarika, Jones draws our attention to how a system orders Black life both collectively and individually. Jones simultaneously memorializes Joshua Beal, Malissa Williams, and Tarika Wilson. But rather than reproducing images of their corpses, he offers us instead postmortems of a structure and system that is itself broken. Here also the evidence in the stitching, raised and prominent, alerts us to the constructedness of this system in order to denaturalize it. We see its “visible seams” and its “frays,” available to be pulled and undone.34 And in this we begin to see the “contradictions that the grid sustains rather than resolve[s] . . . holding in tension what it would seem visually to repress.”35 Jones encourages us to see like a state and also to see and name those racially profiled, those brutally abjected, marginalized by the state and its representatives, in order to see the state itself.

Josh Begley, Officer Involved

Data artist Josh Begley has long been concerned with how to register and thereby counter the banalization of violence that is at once enabled and normalized by digital technologies. His Metadata app, for example, sent a push notification to users’ smartphones every time the news reported a US military drone strike in the world.36 Begley wants us to consider what we do with that information; how does that knowledge transform the rhythm of our day? Begley is one of a number of contemporary artists who aim, in the words of artist Richard Mosse, “to use the technology against itself to create an immersive, humanist art form.”37

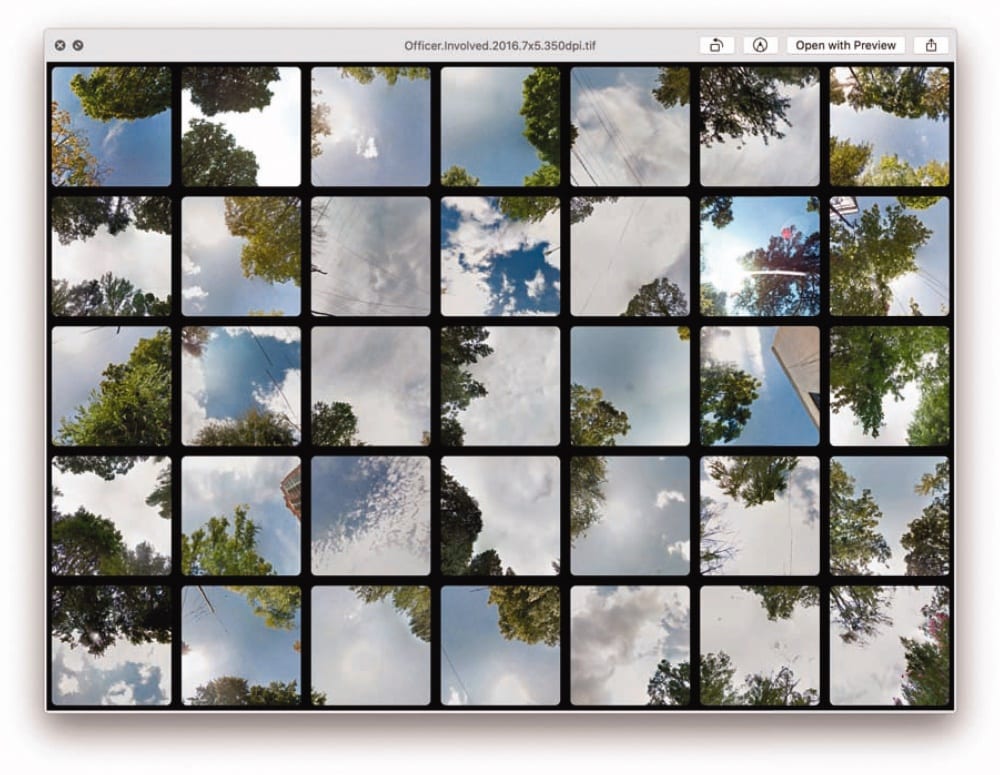

Officer Involved 2015, 2016, and 2017 are part of a body of Begley’s work that uses Google Maps against itself—or at least to tell a different story.38 For Officer Involved 2015, Begley cataloged all the sites in the United States where police killed civilians that year. Based on the published databases of the Guardian and the Washington Post, Begley took “the geographic coordinates of all these places and [ran] them through a script that returns an image for each location.” He then arranged the images, bird’s-eye or street-level views, into a grid of landscapes, mostly devoid of people. When we toggle over an image, we get the name of the person killed and the city and state in which this site is located.

If we click on the image, we get a closer view of these landscapes, and now we can see clearly the Google stamp and copyright. For much of the satellite work in other projects, Begley removes the logo. But “in this case,” he says, “I think it is important to keep. Retaining the logo reinforces the idea that these are images made by machines—what Teju Cole called the ‘all-seeing eye of Google.’ Also because the ‘camera,’ so to speak, is not mine—I am simply an amateur network technician.”39 We are seeing as well “the last thing that some other human being saw,” as Teju Cole wrote of the project. “It is an immersion in the environment of someone’s last moments.”40 This history and these memories are written in the landscape—we just have to know how to read it. It also reminds us that not only is the technology not neutral, but the technology is witness to a crime.

Officer Involved 2016 is a sort of reprise, a means to recognize and record the “ditto ditto” of the archive.41 Significantly, 2016 moves from a static grid formation to film. In one minute and twenty seconds, we now have a sense of movement as well as a soundtrack. “Police violence in this country can feel almost metronomic,” Begley has written.42 In the turn to film, the artist at once invokes this beat—persistent, unrelenting—but also troubles and disrupts it. Whereas a metronome is steadying, Begley’s film is disorienting, nauseating even, reminiscent of Frantz Fanon’s descriptions of “the embodied psychic effects of surveillance . . . nervous tensions, insomnia, fatigue . . . lightheadedness.”43 These sensations are amplified by the use of music: consider the way the artist has chosen to repeat and draw out André 3000’s lyric in the Frank Ocean song “Solo”:

So low that I can admit

When I hear another kid is shot by the popo

It ain’t an event no more

(No more no more no more) 44

“No more no more no more” is slowed down to the point of distortion; these become the final words that ride us out through the remaining half of the film. This is where Officer Involved 2016 finds us and leaves us: in the place where the metronome of banality becomes refusal and turns instead to a slow recitation of protest.

If the rate of death at the hands of police is metronomic, the Black male victim has become metonymic. In what is understood as a crisis almost exclusively confined within Black and Brown communities, and almost exclusively to Black and Brown men, the Black body has come to stand in for or represent what is truly a widespread problem of policing. These groups make up about 23 percent of the deaths represented in Officer Involved 2016, clearly still out of proportion to their numbers in the population at large. However, such metonymy hampers our means of understanding the police power as a systemic feature and key structure that orders American life along axes of race and gender and class. As a form of organizing, such metonymy allows these systems to perpetuate themselves by minoritizing the movements against them. That is to say, understanding this as an issue experienced by Black people alone potentially isolates Black movements (like Black Lives Matter) and thus widespread support for the issue (in part because many white people act in their own self-interest).

This is not to disavow the especial vulnerability of Black and Brown people to a racial profiling that has led to a one-hundred-year-plus epidemic of murder at the hands of state representatives. Rather, it is to highlight how the turn to figuration and the value placed on certain notions of the recognizable and representable human in order to make claims on the state can potentially fall short when such recognition relies on valuing the portrait of Black life alone, without seeing and giving shape to an abstracted whiteness that creates conditions for living, breathing freedom that are impossible for a range of subjects.45 Further, such intense focus on the picture of Black suffering not only allows whiteness to remain shadowy and amorphous but also allows white people to deflect and defer personal action, to mistake empathy for sustained structural critique.

So, how to represent such abstracted whiteness? What is a “true likeness” of white supremacy?

Officer Involved 2016 outlines such a portrait through a perspective change, altering what Google refers to as “pitch” by ninety degrees. Begley again: “Much of my work involves satellites: assembling images from what can be seen by looking down at the landscape, looking down at dots on a map. But what happens when the data points look back? . . . What if Street View cars could be scripted to look skyward?”46

This turn skyward is more than clever technical manipulation. I imagine this shift as turning us in four ways. First, it turns us away from the earth and the body. The turn skyward is the refusal of an imperial gaze and a “visible spatial project” that makes all of us available for consideration, documentation, surveillance, emplacement. As McKittrick writes, “Practices of domination, sustained by a unitary vantage point, naturalize both identity and place, repetitively spatializing where nondominant groups ‘naturally’ belong,” which “determines where social order happens.”47 In turning so, Begley’s images function as a sort of antiportrait, a refusal to participate in the performative fiction of the portrait, with its promises to reveal a subject’s interiority and depth and its aspirations to recognition and reciprocity. As an antiportrait, this turn offers space, breathing room to Black people. If we understand the structuring logic of Google Maps and the broader surveillance state that undergirds it as fundamentally doing racialized work—making bodies Black, “coding [those bodies] for disciplinary measures that are punitive in their effect,” then Begley’s work challenges that logic by making the technology see and say differently. It is an act of what surveillance studies scholar Simone Browne calls “dark sousveillance.” Building on the idea of “sousveillance” as the “active inversion of the power relations that surveillance entails,” Browne defines dark sousveillance as the “tactics employed to render one’s self out of sight, and strategies used in the flight to freedom from slavery as necessarily ones of undersight. . . . Dark sousveillance,” she continues, “plots imaginaries that are oppositional and that are hopeful for another way of being.”48

As stated earlier, my ultimate goal is not to turn us away from the joys and pleasures of (Black) embodiment. Nor is it to deny the traumas and scars that Black bodies bear. There is knowledge and memory in the body. Nor is my goal to devalue or dismiss figurative art practices. But following James Baldwin, Black folks can’t be free until white folks can free themselves from the structures and systems of privilege that bind them and subsequently the rest of us. For this to happen there needs to be not less embodiment but a moment beyond the complex constellation of visibility in which Black people remain “a fixed star . . . an immoveable pillar,” to use Baldwin’s incisive description, to clear the way for the honest and rigorous solidarity and organizing work upon which true structural change is built.49 Thus, the second turn is away from the kind of embodiment or empathetic sight that Teju Cole notes as a feature of Officer Involved 2015. We are no longer immersed in the last moments of someone else’s life, facing a landscape written in blood. Instead we are made to watch and listen to a fairly indistinguishable sky. We are in a kind of new unknowable. It is the achievement of the Hartman-inspired move away from a liberal-humanist empathetic hand-wringing that prompted Begley from the start.

In removing the body from sight and shifting our gaze, we must ask ourselves, with whose eyes are we seeing? When turned this way, the images become abstracted, and the technology is forced to look back at itself. This third turn we might identify as one toward a forced self-portrait of power: a self-portrait of a structure in which it reveals itself.

And in its place we are returned to our own sensations, the “certain uncertainty” of the “bodily schema.”50 It is this skyward look that alerts us that the all- seeing eye of Google has been abstracted but that it is the human who sees and makes meaning: humans who code and humans who kill. The skyward look induces physical sensations—of nausea, motion sickness, eye tics, and disorientation—and these sensations remind us that though we may see with a god-eye, we are not god.

Officer Involved 2016 offers a 360-degree turn, a “considered choreography” that begins with the Black body and returns us to our humanity.51

After the Fires

I first started writing this essay in the early months of the quickening durational catastrophe that is the Trump presidency. It was clear then as it is now that we are in a moment of great urgency. White supremacy, in all of its manifestations as, and intersections with, xenophobia, capitalist domination, violent patriarchies, dangerous mastery of the environment, and rampant fascism, needs to be dismantled. Just to be clear, white supremacy is a disease that is killing all of us and this planet above all. I believe with all my heart that art and visual culture are imperative, if not central, to this fight. That is, art and visual culture are fundamentally necessary to decolonizing our sight. The protests surrounding Open Casket demonstrate that the stakes of this work are high. Our work is to recognize how white supremacy functions as a way of seeing that any person of any race or positionality can work to undo. Our work is to identify and interrogate, challenge and dismantle the systems that make fear and hate, injustice, and expendability possible and profitable—that discipline us to see like the state and forget our own humanity.

Leigh Raiford is an associate professor of African American studies at the University of California, Berkeley, where she teaches and researches about race, gender, justice, and visuality. She is the author of Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle (University of North Carolina Press, 2011) and coeditor, with Heike Raphael-Hernandez, of Migrating the Black Body: Visual Culture and the African Diaspora (University of Washington Press, 2017).

- See Richard Pérez-Peña, “Woman Linked to 1955 Emmett Till Murder Tells Historian Her Claims Were False,” New York Times, January 27, 2017. Bryant recanted her story in an interview with historian Timothy B. Tyson, fully explicated in his book The Blood of Emmett Till (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2017). ↩

- Teju Cole, “Death in the Browser Tab,” in Known and Strange Things (New York: Random House, 2016). ↩

- See Hannah Black, “Open Letter,” printed in Alex Greenberger, “‘The Painting Must Go’: Hannah Black Pens Open Letter to the Whitney about Controversial Biennial Work,” ARTnews, March 21, 2017. See also Aruna D’Souza, Whitewalling: Art, Race and Protest in Three Acts (New York: Badlands, 2018). ↩

- Black, “Open Letter.” ↩

- Aruna D’Souza, “Who Speaks Freely? Art, Race, and Protest,” Paris Review, May 22, 2018. On a “constellation of disagree ments,” see Gregg Bordowitz’s comments in “Cultural Appropriation: A Roundtable,” Artforum, Summer 2017. ↩

- See especially Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011). ↩

- Leigh Raiford, “Photography and the Practices of Critical Black Memory,” History and Theory (Winter 2009). ↩

- Ida B. Wells’s short essay “Lynch Law” was published in the collection The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition. ed. Wells (1893; reissued in a volume edited by Robert W. Rydell, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999). The image is a drawing made from a photograph; because white audiences doubted the veracity of that drawing, Wells reproduced the photograph itself in the pamphlet A Red Record (1895). ↩

- Siddartha Mitter, “‘What Does It Mean to Be Black and Look at This?’: A Scholar Reflects on the Dana Schutz Controversy,” Hyperallergic, March 24, 2017. ↩

- Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument,” New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (Fall 2003), 260. ↩

- Katherine McKittrick, “Yours in the Intellectual Struggle: Sylvia Wynter and the Realization of the Living,” in Sylvia Wynter on Being Human as Praxis, ed. McKittrick (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 3; Sylvia Wynter, “‘No Humans Involved’: An Open Letter to My Colleagues,” Forum NHI: Knowledge for the 21st Century 1, no. 1 (Fall 1994): 44. ↩

- “Aspiration is the word that I arrived at for keeping and putting breath in the Black body.” Drawing on Black feminist scholarship, most notably Patricia Hill Collins’s Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (New York: Routledge, 1990), Sharpe insists on an ethics of care as a means of “reimagin(ing) and transform(ing) . . . spaces where we were never meant to survive.” And she argues for an ethics of seeing that “refuse(s) . . . to frame someone else’s not seeing, to abet our thingification.” Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 130, 131, 133. ↩

- James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), 4, 3. ↩

- “Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on . . . an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.” Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party (1888; orig. 1848), in Karl Marx, The Revolutions of 1848: Political Writings: Volume 1 (London: Penguin Books, 1973), 68. ↩

- Stuart Hall, “New Ethnicities” (1989), repr. in Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, ed. David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen (New York: Routledge, 1996). For more on the limits of “positive images,” see Michele Wallace, “Negative/Positive Images,” in Wallace, Invisibility Blues: From Pop to Theory (New York: Verso, 1990). ↩

- Hall, “New Ethnicities.” ↩

- Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007). ↩

- English continues an interrogation of the limits of “Black Art” as a category, particularly as it adheres to and diverges from abstractionist art, in a later study, 1971: A Year in the Life of Color (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016). These debates, of course, took place in real time. See artist Raymond Saunders’s pamphlet Black Is a Color (1967), reprinted in Darby English, 1971. The pamphlet was an abbreviated version of an essay Saunders had written in response to poet and novelist Ishmael Reed’s championing of the explicitly nationalist Black Arts Movement; see Saunders, “The Black Artist: Calling a Spade a Spade,” Arts Magazine, May 1967, 48–49. In 1971, Tom Lloyd, whose abstractionist light sculptures were featured as the inaugural exhibition of the Studio Museum in Harlem, edited and published Black Art Notes. With contributions from Amiri Baraka, Jeff Donaldson, and others, Black Art Notes is not only interested in the forms “Black art” might take but argues for the need to dismantle a Eurocentric arts world—critics, curators, museums, arts councils, art historians—that excludes Black artists from the financial and cultural access afforded by institutional recognition regardless of the art they make. Tom Lloyd, Black Art Notes (n.p.), 1971. ↩

- Ann Gibson, Abstract Expressionism, Other Politics (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997). ↩

- Phillip Brian Harper, Abstractionist Aesthetics: Artistic Form and Social Critique in African American Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2015), 4. See also Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), in which she writes, “Citizenship presupposed the equality of abstract and disembodied persons, and this abstraction disguised the privileges of white men,” 153. ↩

- Jerry Brotton, A History of the World in Twelve Maps (New York: Viking, 2013), 2. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 256. ↩

- Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Conquest (New York: Routledge, 1995). ↩

- Randy Kennedy, “White Artist’s Painting of Emmett Till at Whitney Biennial Draws Protests,” New York Times, March 21, 2017. ↩

- “However, what I am trying to suggest is that if the scene of beating readily lends itself to an identification with the enslaved, it does so at the risk of fixing and naturalizing this condition of pained embodiment and . . . increases the difficulty of beholding Black suffering since the endeavor to bring pain close exploits the spectacle of the body in pain and oddly confirms the spectral character of suffering and the inability to witness the captive’s pain. If, on the one hand, pain extends humanity to the dispossessed and the ability to sustain suffering leads to transcendence, on the other, the spectral and spectacular character of this suffering, or, in other words, the shocking and ghostly presence of pain, effaces and restricts Black sentience.” Hartman, Scenes of Subjection, 21. ↩

- Tina Campt, “Black Visuality and the Practice of Refusal,” Women and Performance: Ampersand, February 25, 2019. ↩

- Torkwase Dyson, “Black Interiority: Notes on Architecture, Infrastructure, Environmental Justice, and Abstract Drawing,” Pelican Bomb, January 9, 2017. See also Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, “African American Abstraction,” in The Routledge Companion to African American Art History, ed. Eddie Chambers (New York: Routledge, 2019), 159–73. ↩

- See Antuan Sargeant, “Striking Deconstructed Book Paintings Challenge American History,” Vice, December 29, 2016. ↩

- Leah Ollman, “Unbinding the System,” Art in America, April 2015, 96. ↩

- Rosemary Regina Sobol and Grace Wong, “Officer Fatally Shoots Man after Road Rage Incident in Mount Greenwood,” Chicago Tribune, November 5, 2016. ↩

- See Katherine McKittrick, “Mathematics Black Life,” in “States of Black Studies,” special issue, Black Scholar 44, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 16–28. ↩

- Rosalind Krauss, “Grids,” October 9 (Summer 1979): 50; Harper, Abstractionist Aesthetics, 46. See also Lex Morgan Lancaster, “Feeling the Grid: Lorna Simpson’s Concrete Abstraction,” ASAP/Journal 2, no. 1 (January 2017): 131–55. ↩

- Naima J. Keith and Dana Liss, “Artist x Artist: Mark Bradford and Samuel Levi Jones,” in Studio: Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine, Winter/Spring 2015, 49. ↩

- On “visible seam,” see Nicole Fleetwood, Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality and Blackness (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). On “fray,” see Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art and Textile Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017). ↩

- Lancaster, “Feeling the Grid,” 138. ↩

- Josh Begley, “After 12 Rejections, Apple Accepts App That Tracks U.S. Drone Strikes,” Intercept, March 28, 2017. ↩

- Richard Mosse, Incoming, Barbican Centre, London, February 15–April 23, 2017. ↩

- I focus here on the 2015 and 2016 iterations. ↩

- Josh Begley, email message to author, December 23, 2016. ↩

- Teju Cole, “Officer Involved,” Intercept, June 9, 2015. ↩

- “The details and the deaths accumulate; the ditto ditto fills the archives of a past that is not yet past.” Sharpe, In the Wake, 73. ↩

- Josh Begley, “Officer Involved 2016,” Intercept, December 21, 2016. ↩

- Frantz Fanon, quoted in Simone Browne, Dark Matters (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 21. ↩

- James Blake Litherland, André Benjamin, and Christopher Edwin Breaux, “Solo (Reprise),” performed by Frank Ocean, track 10 on Blonde, Sony, 2016 (lyrics © BMG Rights Management, Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC). ↩

- Sharon Sliwinski, Human Rights in Camera (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). ↩

- Josh Begley, email message to author, December 23, 2016. ↩

- Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xv, xiv. ↩

- Browne, Dark Matters, 17, 19, 21. ↩

- James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (1962; repr., New York: Vintage, 1993), 9. ↩

- Frantz Fanon, “The Fact of Blackness,” in Black Skin, White Masks (1967; repr., New York: Grove Press, 2008), 110. ↩

- Jasmine Elizabeth Johnson, Rhythm Nation: West African Dance and the Politics of Diaspora (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming). ↩