Karen Tei Yamashita: In many ways this conversation between us started many, many years ago.

Boreth Ly: Yes—it was at your home in Santa Cruz, California, in your kitchen. A conversation we had over a lavish breakfast you cooked for us.

Yamashita: So it was. And at that time I also invited three scholars of ancient philosophy and culture. All were classical scholars. I thought that maybe you would have some kind of conversation between you, and I would sit there and get the benefit of it: Gildas Hamel, who is a scholar of ancient Palestine; Roshni Rustomji-Kerns, whose research focuses on classical Greek and Sanskrit literature; and you, Boreth Ly, on ancient Hindu and Buddhist arts of Southeast Asia.

Ly: I remember we had a conversation centered on the question of forgiveness. We explored how cultures have different terms/words for this idea, concept, and process in varied languages. You and I also share a love for the late Toni Morrison’s writings, and we have spoken at length about her lecture on forgiveness, a talk that she gave in Santa Cruz in 2014. Forgiveness is a very important topic, but we don’t have time to go into detail on this theme here. My French and Cambodian friends and colleagues in France are also very interested in forgiveness, so perhaps we can revisit this topic together in the near future.

Yamashita: Can you tell us about your personal journeys to your scholarship and to your research interests?

Ly: I began my academic career writing about ancient Hindu and Buddhist arts of Southeast Asia, especially visual narratives of the Hindu epics The Mahabharata and The Ramayana on ancient Khmer stone temples. However, since I am a survivor of the genocide in Cambodia, that atrocity and its traumatic legacy have always loomed in the background—haunting me. I knew that I had to confront that topic eventually, but I repressed it in order to survive my initial displacement as a refugee in the United States.

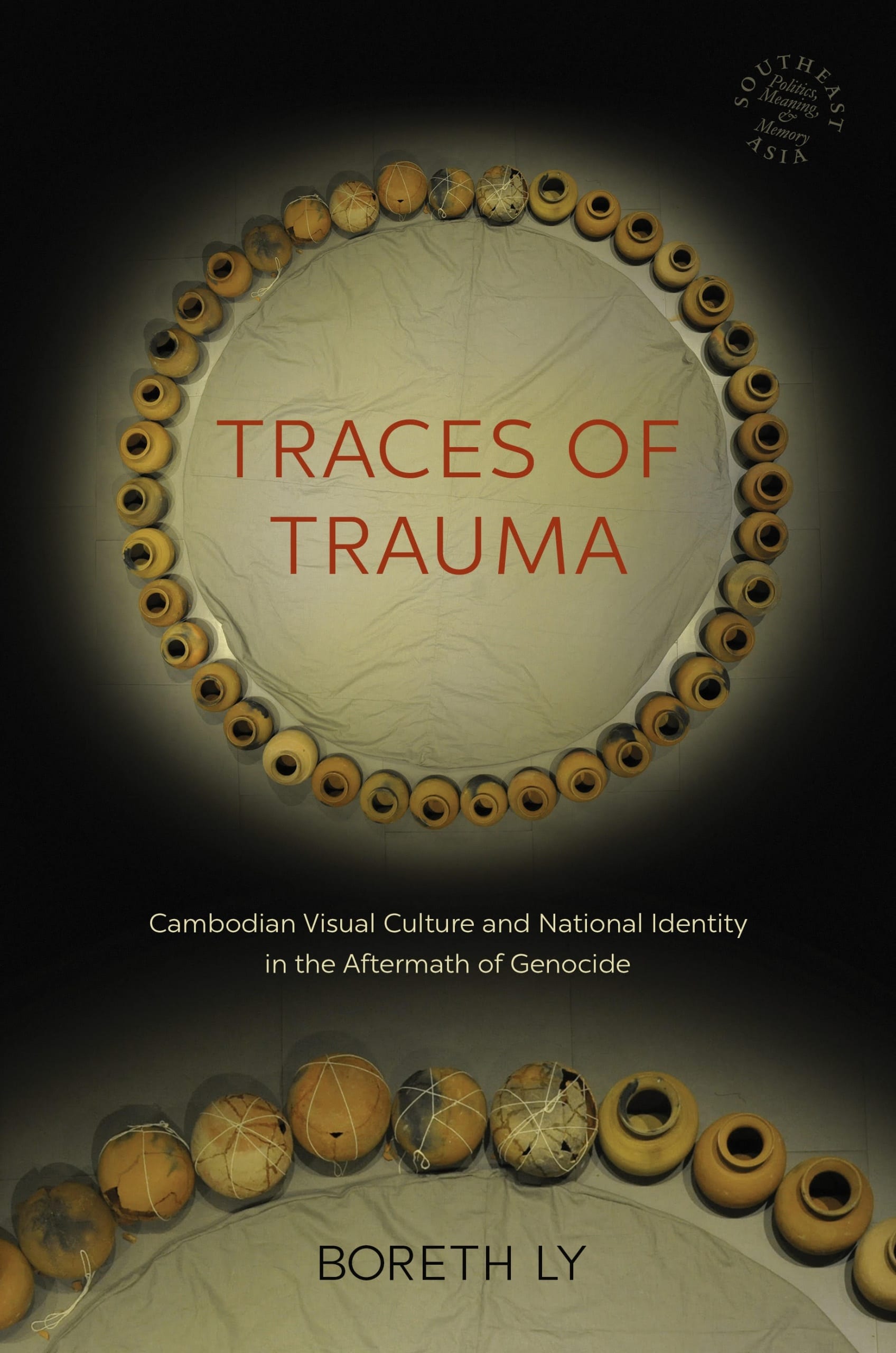

As I mentioned in the preface to my book, Traces of Trauma: Cambodian Visual Culture and National Identity in the Aftermath of Genocide [University of Hawai‘i Press, 2020], in the early 2000s I began to write about my memory, history, and experience of trauma under the Khmer Rouge regime and how that intersected with my melancholia in the United States. This long predated the current popularity of refugee studies. In fact, one of the first essays that addressed the loss of my close family members and childhood was published in a 2003 issue of Art Journal: “Devastated Vision(s): The Khmer Rouge Scopic Regime in Cambodia.” I went on “to experiment with experience,” to borrow a phrase from the English novelist Jeanette Winterson. However, I encountered great discouragement from some of my colleagues in the field of Southeast Asian art history. One of them said that the insertion of my voice interrupted the discussion of—and thus blocked serious analysis of—art objects in the text. After reading “Devastated Vision(s),” another colleague in Southeast Asian studies said, “It is all about Boreth Ly.” By that she meant that I was commodifying my own life, memory, and history. In brief, they found my writing too personal and autobiographical. I am not surprised in retrospect; art historians are academically trained to write “objectively” about the lives of objects and quite often never question their strange fetish for objects, especially art objects from another culture. It really resonates with what the late Edward Said said, in 1978 book, Orientalism: “The East is a career”—a parasitic career.

I mention the discouraging remarks from these two colleagues not because they stopped me, but to create a safe and healthy space for my students and colleagues who might have shared similar experiences. I want people to be able to make sense of their own lives, history, and memory and the art objects that they chose to write about. Moreover, it is my way of reclaiming our humanity and dignity that was discouraged, dehumanized, and erased in the names of science, scholarly conventions, and “objective” styles of discourse. Indeed, our lives matter!

Readers will see that my voice and perspective on the historical events, artists, and art objects form the bookends to the five chapters situated in between. And my voice can be heard like a ghost guide in the background, haunting the pages in different chapters.

I have come full circle because my earlier writings on the two Hindu epics, especially The Mahabharata, helped me think through issues such as collective and individual courses of action and the consequences that are imposed on the collective and vice versa. After all, the philosophical underpinnings of these epic poems are about ethics, morality, conflict, and reconciliation. I was delighted to learn from an interview with the theater director Peter Brook that his film adaptation of The Mahabharata was inspired by the conflict over the Vietnam-American War.

Last, as I also point out in my book—the compartmentalization and periodization of art history and focus of the discipline is very Western. It is ironic because the term “interdisciplinary” has been discussed in European American approaches to the study of art history, and yet there are so many constraints and boundaries imposed upon our approaches to writing about art, subjectivity, gender, sexuality, and race.

Yamashita: Rithy Panh, the filmmaker, whose work you discuss, says he makes his films because he has lived to tell the story. He is Ishmael. And so he has this responsibility. Can you talk about responsibility?

Ly: I think many survivors of totalitarian regimes and genocides shoulder the burdens and responsibilities of narrating and making sense of these violent events and what impact their traumatic legacy has on their respective communities and ethnic groups. Recently, I rewatched Rithy Panh’s 2018 film, Graves without a Name, in which the director attempts to tell the story of how he participated in a Khmer Buddhist memorial ritual in order to make peace with relatives who died in the genocide and who were buried in unmarked mass graves. Likewise, my responsibility is to make peace with the ghosts of my close family members and many Cambodians who died unjustly. My book centers on how Cambodian artists in the homeland and diaspora come to terms with these restless ghosts; the traces of their remains are scattered in the land, and they continue to haunt me and us.

Yamashita: I’d like to talk about the art that graces the cover of the book. This is the work of Ly Sundari, or Amy Lee Sanford, her American name. She was a young girl saved and sent to the United States for adoption. Many years later, her adopted mother gave Sanford her father’s letters to read, and she began to discover another story about herself, encouraging her to return to her childhood village. There, she began to make these pots. As you can see, she made but also broke them, and then carefully reconstructed them again. I was reminded of Ai Weiwei’s broken vessels and his breaking of vases, but I can’t imagine Ai Weiwei reconstructing every pot. You write in this context about the Khmer word baksbat, which I understood to mean “broken body.” Can you speak to the broken body and to Sanford’s work?

Ly: As I have discussed in my book, the Khmer term for trauma is baksbat, a broken body that leads to a broken spirit. Amy Lee Sanford’s 2012 installation/performance Full Circle captured poignantly this local Khmer perspective and understanding of trauma and the broken body. It is about her need to return to her place of birth and to make peace with her father’s ghost. She went to Kampong Chhnang, a village in Cambodia well known for the making of clay pots. Kampong Chhnang is also where her father came from. She turned forty that year, so she arranged forty clay pots in a circle. She stood in the middle of the circle and picked up one pot at a time and dropped it on the ground so that it shattered into pieces. Then she sat in the middle of the circle and glued the pieces of each pot back together. The painstaking labor and endurance of time in piecing these fragments back together, knowing that some broken pieces are irreparable and that the pot can never be completely be whole again, capture poignantly the Khmer Rouge genocide or “autogenocide.” Moreover, the artist’s endurance represents resilience.

Yes, I agree with you that Ai Weiwei in his performance broke his antique pots as a statement questioning the value of art in a consumer society, but he does not have to be burdened with mending them. In Sanford’s performance, however, the broken pots represent the burden of Cambodians at home and in the diaspora having to mend the pieces of these broken pots as an attempt to be whole again. Of course, we know that it is impossible. We are compelled to live with this obdurate scar of trauma. Sadly, the next generation, especially Khmer Americans in the diaspora who were born in the refugee camps, inherited this trauma due to their parents’ displacement.

Yamashita: I think what’s powerful about Sanford’s work is a desire to repair and to heal—and so then to reconstruct the pots. In her work, I found great hopefulness along with your ideas of repair and resilience, and I thank you for that.

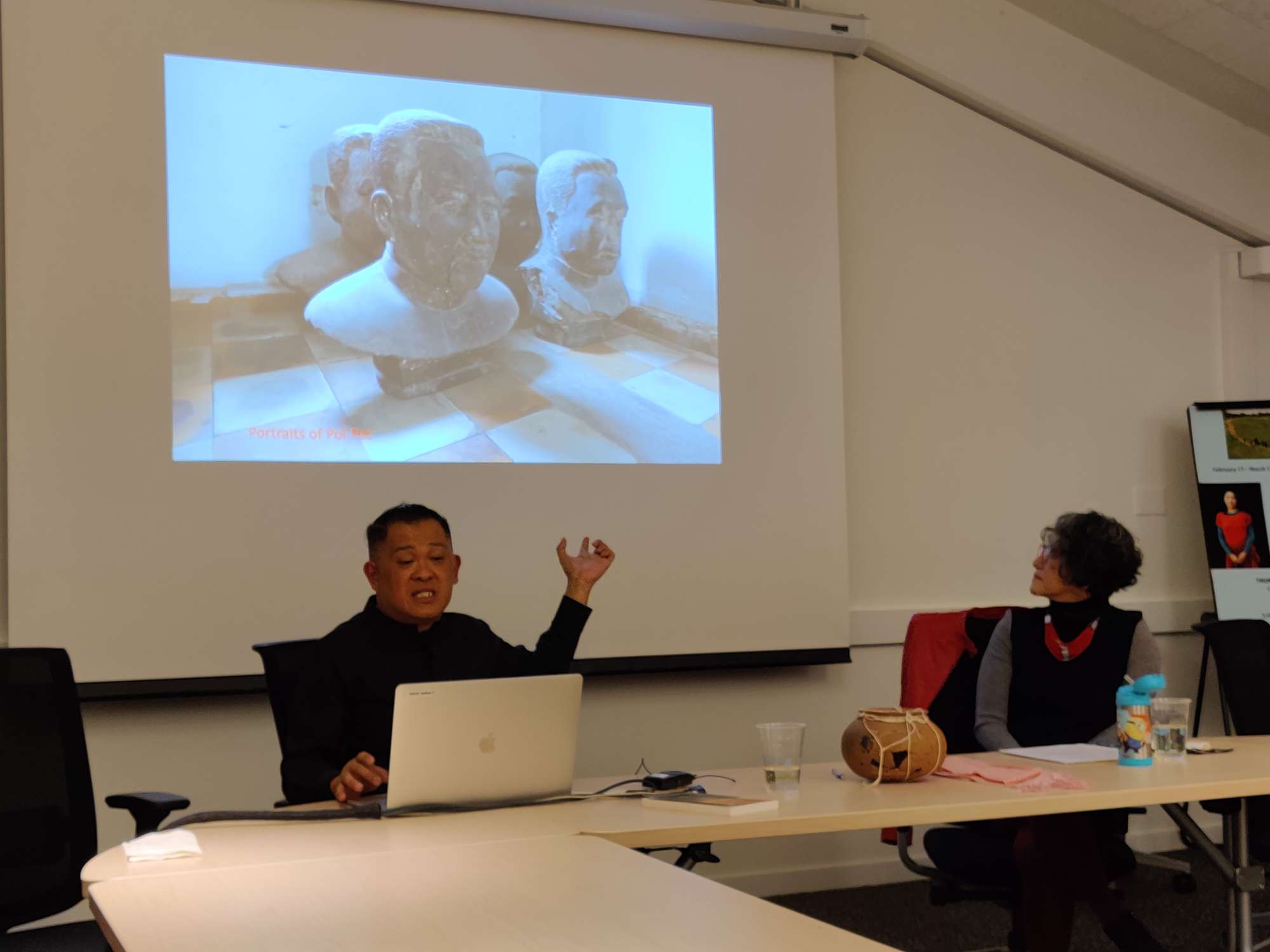

Now, I want to move on to politics—in the case of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, the power of politics to control art. One of the ironies you speak of is that some of the artists who were in prison during the regime were saved because they could reproduce a portrait of Pol Pot. What would you conclude about art and politics and the danger of their merging?

Ly: In Traces of Trauma, I referenced what Walter Benjamin wrote in his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” He pointed out that under Fascism, there is an “aesthetic of politics,” but under Communism, it is about “the politics of aesthetics.” Furthermore, your question reminds and cautions us that when the production of art is engineered to serve a specific political ideology, the consequences can be deadly.

Yamashita: When I think about ideology, I think ideology is a desire to make order. But for anything to be ordered, you have to leave some things out. And I think we need to be very wary of that. Some things have to be disposed of. One of the documentary films by Rithy Panh is about Duch, the director of S-21, the Tuol Sleng prison in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. At the time he was still alive, in prison, given a court trial. Duch says this: “Ideology is criminal. We went down this road to the end. Wickedness and cruelty aren’t ideological. I want to make two things clear. What I did was criminal, but I was serving ideology. I was ordered to commit these crimes.”

Ly: This is an interesting and complex question and I will try to answer it concisely. Recently, I reread the late Doris Lessing’s 1962 novel, The Golden Notebook, in which one of the characters utters in passing, “Something is cracking.” By this, she hints at the shattering and fracturing of a collective utopian vision after the fall of Communism. Lessing, who was born in the racially segregated colonial Rhodesia, became a fan of Communism in the 1950s upon her return to England. In an interview, she recalled her disappointment and how painful it was for her to accept the fall of Communism in the Eastern Bloc. Her way of responding to this shattering of a social utopian ideology was simply to hint at it in the narrative of her novel, as I mentioned.

Likewise, many Khmer intellectuals of the generation of Saloth Sar (aka Pol Pot) who went to study in Paris were introduced to and subsequently became enamored with Communism and later Maoism. They returned to Cambodia and tried to implement these utopian ideas of egalitarianism; the result was a failed revolution that ended with a genocide that killed 1.7 million of Cambodia’s population. I recall you once said to me in one of our conversations, “One person’s political utopia is another person’s genocide.” Indeed, one of the central points of my book is precisely about this political dogmatism: the danger of moral self-righteousness and the disastrous consequences of an individual ideological purity and political fanaticism. Despite my lived experience of the horrific Khmer Rouge revolution, I still believe in a socialist state. In short, it is the corrupt leadership that is to be blamed and not the idea.

Yamashita: I want to go back to one thing about Pol Pot and this policy called kamtech, which is to “wipe out the past.” So you start at zero with an agrarian revolution in Cambodia. There’s kamtech, and everything that’s gone before is wiped out—the history, the colonization by the French. But what is kamtech? I mean, in a sense, it’s another colonization. What would you say?

Ly: Yes, one can read it that way. Of course, the irony about the Khmer Rouge revolution (or, any political and cultural revolution) is they thought they were getting rid of the feudal society of Cambodia by advocating and implementing an agrarian revolution. In that sense, it is a colonization of the urbanites. Furthermore, what is most interesting to me is how the present leadership and elite families who share current governing powers have returned to the same old feudal ways of life, a patron-clients way of sharing power and wealth in contemporary Cambodian society. In brief, nothing has changed—or as the French say, “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.”

Yamashita: Panh’s films are amazing. There is the social documentary about Duch, but there’s also a kind of reenactment of the guards and those men who were survivors of his death prison. In one film, survivors (many of them were artists) and guards meet and go through their daily routine as they worked in the prison at the time. Then there’s a conversation between them, and that was very powerful. Did this encounter achieve any kind of reconciliation?

Ly: Yes, I remember watching those chilling reenactments performed by former prison guards. I call them the dance of cruelty. These perpetrators’ bodies remember the torturous acts they carried out in those haunted rooms. I think what the perpetrators, artists, and survivors learned was not so much about reconciliation, but that they were victims of a dogmatic political ideology that was vertically imposed upon them. I think this question of and potential for a reconciliation is related to Theodor Adorno’s questions that I quoted in my book. The ethical and moral compass that guided daily human actions has completely turned upside down in the aftermath of this genocide or autogenocide. It is about a difficult dialogue that needs to take place between survivors and perpetrators. I remember meeting a young Khmer colleague in Cambodia who said to me: “Brother, you are not a survivor, we are all survivors; the perpetrators are also victims.” I was flabbergasted! It returns to the question of accountability and forgiveness that we talked about earlier. Clearly, there is a need to hold those responsible for the genocide accountable. With regards to the need to forgive: I am still pondering this question. In Buddhist ethics, there is no need to forgive, because one’s karma is determined by one’s action and so karma is the judge of one’s evil deeds and actions. In brief, it is beyond one’s needs to forgive or not to forgive.

This “beyond forgiveness” in Buddhist philosophy might explain why Kaing Guek Eav (aka Duch), the director of the Tuol Sleng prison S-21 whom you mentioned earlier, converted to Christianity. He read his Bible religiously in his detention cell during his tribunal hearing. In the Christian religion, one can be forgiven for one’s evil deeds, but not in Buddhism. I doubt that he was sincere about his new faith. I am cynically inclined to think it was a political move on his part. At any rate, he died a natural death at the age of seventy-seven on September 2, 2020.

I can only raise this question of forgiveness in my book; the answer remains for the individual and the collective to decide. Clearly, there is no easy answer, especially in the context of a tragedy of this magnitude when 1.7 million people were murdered. As I have discussed in my book, the arts can only help to engage us in this difficult dialogue and serve as catharsis, but they cannot solve this moral and ethical conflict or provide complete healing for the wound.

Again, I am still reflecting and thinking through this question of forgiveness.

I know that the issue of reconciliation is part of your family history and memory of the Japanese American internment camp during World War II in the United States. You wrote about this experience in your 2017 book, Letters to Memory. Do you think reconciliation is possible between the US government and Japanese Americans? What about forgiveness?

Yamashita: I suppose you could say that a reconciliation between Japanese Americans and the American government has occurred, given the redress and apology signed into law in 1988. Although, by 1988, most issei and many nisei who had been imprisoned in those years had already died, and those Japanese immigrants living in Peru who were also expedited to US internment camps were not included. The community itself had to overcome internal differences and to compromise to find a common purpose; what individual members understand about this “reconciliation” is complicated. My generation was largely born after the war, and as you know, we have inherited the trauma of this memory. I think perhaps that reconciliation is an ongoing process of education and understanding. It cannot be finished but must find a space of meeting, a tentative peace, on alert, because as my folks would say, this history must not be repeated.

Forgiveness is another response. It was Gildas Hamel who made me aware of forgiveness—“a very powerful idea,” he said. In writing about my father, his experience of the war, and its aftermath, I realized his profound belief in the power of forgiveness, that it was necessary in order for him to continue to live and work after the sorrow and horror of war.

Ly: Again, we can revisit this poignant topic in the near future.

Yamashita: If I remember correctly, a section of Traces of Trauma was about the re-creation of the fabric and patterns of krama, used in the scarves appropriated by the state and used by the people. I think you talked about national identity in relationship to krama. This made me think about the idea of a national and/or cultural identity. In order to mobilize a group of people, they would have to be bound by an identity. But the participation in the self-destruction of that group in order to “purify” that identity had deathly consequences. It becomes impossible to walk away from such participation and identification without wondering who we have become. When Hannah Arendt speaks of the “banality of evil,” it is about an identity that we name monstrous even as we do not think of ourselves as monsters. Who have we become? Participants and onlookers. Does this make sense?

Ly: In a chapter of my book, I discussed the politicization of krama, a checkered scarf made of cotton that serves multiple purposes. This piece of clothing originated in villages. When the Khmer Rouge came to power, they appropriated it. Subsequently, it became one of the indispensable components of their black pajama uniforms. Interestingly, contemporary Cambodian society has co-opted it as one of the symbols of Khmer national identity. In fact, in 2018, Cambodia set the Guinness World Record for the world’s longest handwoven krama. The scarf measured 1,149.8 meters long and it is now on display at the National Museum in Phnom Penh.

I somewhat agree with Hannah Arendt that we are all implicated in the working of political ideology and in that sense we are all “monsters.” However, there are exceptions. A case in point is when one considers transnational identity, especially individuals who are biracial and bicultural. For example, the late Vietnamese Cambodian artist Lê Huy Hoàng (1967–2014) created an installation, Krama, in 2009. It is about his struggle with his biethnic and bicultural identity and his longing and belonging to both nations. He belonged to both ethnic groups, but he was never accepted by either one of them. The artist used palm sugar, cane sugar, and used coffee grounds as materials to paint a large checked scarf on the ground of a gallery in Hanoi. The artist compared his Khmer ethnicity to palm sugar and his Vietnamese side to white cane sugar, and the used ground coffee represents his bitterness at being excluded by both ethnic groups. This installation addresses the issue of belonging and unbelonging to a nation state. It is about citizenship, identity, inclusion, and exclusion.

Yamashita: Talk a little bit about dance and the meaning of the dance called “Neang Neak,” because I think its meaning is perhaps at the center of the book. Its representation of the serpent and her poisonous tail involves a mythic story about the Cambodian nation.

Ly: In the last chapter of my book, I discuss the founding myth of Cambodia. Neang Neak, the mythical mother of the Khmer ethnic group, is a serpent princess who married a Brahmin from India. The couple gave birth to the Khmer race and thus the Khmer Kingdom. In 2005, a Khmer court dancer and choreographer named Sophiline Cheam Shapiro, who was living in the Cambodian diaspora of Long Beach, California, created a dance called Seasons of Migration comprising four sections. One of these segments is titled “Neang Neak,” and the story references this myth of creation. This extraordinary dance narrates the tale/tail of how Neang Neak immigrated to the United States. In it, we see Neang Neak dressed in glittering court costumes and wearing a golden serpent headdress as she performs a dance that narrates her tale of cultural displacement. Moreover, it tells how she negotiates her cultural identity in a foreign country. She realizes that she is different in that she has a tail. Subsequently, she makes multiple attempts to get rid of it, but she fails. The segment concludes with Neang Neak embracing and accepting her tail/tale and thus her ethnic and cultural identity.

I think one can read this mythical mother figure as a metaphor for the traumatized Cambodian nation and its regeneration after the genocide, like the serpent who is both poisoned and poisonous, yet capable of shedding her old skin. The Cambodian nation can reinvent its identity in the aftermath of this genocide. Furthermore, this tale is reenacted in every Khmer wedding so it also signifies procreation and regeneration of the populations in the aftermath of genocide.

Yamashita: So I’ll quote this from your book: “The experience of trauma is neither poison nor cure, but can contain both poison and remedy. I believe that the same is true of the traumatic experiences that artists expressed in their works and produced in the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge genocide in Cambodia, and its diaspora. They are the poison-cures.” Art as poison-cure. My reading here is that art is necessary as an inoculation of memory to resist repetition, and to resist the erasure of one’s moral and ethical compass. Myth, as it is transformed into dance and story and art, can save us.

Ly: Yes, artists are healers of their own trauma and the collective trauma in their respective communities and nations. I am not saying they are magicians and can provide complete healing; arts have their limitations.

Yamashita: I wanted to end by saying that, while I knew you had to disappear for a time to write, I didn’t know this was your subject—I thought you were doing something else. And you were hidden away writing this. I also thought that of anybody, you would know why my grandmother started to take sumi-e painting lessons while she was incarcerated those years in the internment camp.

Ly: Indeed, you wrote about her art making in the camp in your book, Letters to Memories. The power of art as expressions of trauma and catharsis is part of this legacy of trauma.

Yamashita: I’ve gotten to the end of my thoughts, but one last thing. At first I thought you didn’t have to write this book—that you could have written about Angkor Wat or something distant and esoteric. But then I read your book, and I realized that Ronaldo Oliveira, my husband, was right when he said, “Only Boreth could have written this book.” So you took on that responsibility to write about contemporary artists and trauma.

Ly: It is interesting that you thought I would devote my scholarly career to write only about canonical Cambodian art. I concur with Amy Lee Sanford’s perspective when she told me that she “needed to go backward in order to move forward.” I feel the same. The publication of this book enables me to move forward because I have fulfilled my moral obligation and responsibility in telling the story of how memory, history, trauma, family, and the Cambodian nation and its diaspora intersect and intertwine. More important, I wanted to show how artistic expressions can help open up conversations and heal this personal and collective wound.

I have always been very interdisciplinary in my approaches to writing about art history and visual culture. My book attempts to answer difficult questions by drawing from many types of objects ranging from poetry, film, court dance, and fashion to ancient and contemporary Khmer art. Again, there is a tendency in academia to be so discipline focused that one risks not seeing the “big picture.” Of course, some of these issues can be attributed to insecurity and envious scholars who guard their territories and serve as gatekeepers to their fields and disciplines. Perhaps the late George Steiner might have been right when he said we are living in “the age of envy.”

Last, I have been employing different styles of writing throughout my career. For instance, “Devastated Vision(s),” the article I published in Art Journal in 2003, is structured after the four movements of Gustav Mahler’s Fourth Symphony. Likewise, another essay, “Buddhist Walking Meditations and Contemporary Art of Southeast Asia,” published in positions in 2012, ends with a walk on the serene and beautiful campus of UC Santa Cruz. I believe that different themes, subject matter, and objects require different styles of writing and one must nurture them accordingly. In sum, there is plenty of room for creativity in so-called serious and dense academic writings. To this end, one of my favorite novelists is Italo Calvino; I love his last and posthumously published essays titled Six Memos for the Next Millennium (1988), especially the one, “Lightness.” Contrary to its title, “Lightness” is a very dense essay.

Yamashita: Thank you for your courage and your personal sustenance in this. Thank you. It’s a gift to all of us. And we promised not to cry. Thank you.

Ly: Yes, we made it without crying. I remember you phoned me up after you finished reading my book and you were so sad and moved that you sobbed on the phone. I said, you may not cry because if you cry, I will cry, too, and we won’t go anywhere in the scheduled public conversation.

Thank you.

Note: We would like to thank the History of Art and Visual Culture Department at UC Santa Cruz and Art Journal Open for sponsoring this interview/conversation, which took place on January 28, 2020, at UC Santa Cruz. In addition, we thank Tosh Tanaka for his help with the recording and transcription of the live version of this interview. Many thanks to Nicole Archer and Mirren Theiding for reading drafts of this interview. Finally, we are grateful to Amy Lee Sanford, Anders Jiras, Catherine Ries, Nguyễn Mạnh Hùng, and the University of Hawai‘i Press for granting us permission to reproduce their photographs here.

Boreth Ly is associate professor of Southeast Asian art history and visual culture at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She coedited, with Nora A. Taylor, Modern and Contemporary Southeast Asian Art: An Anthology (Southeast Asia Program Publications, 2012) and is the author of Traces of Trauma: Cambodian Visual Culture and National Identity in the Aftermath of Genocide (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2020). In addition, she has written numerous articles and essays on the arts and films of Southeast Asia and its diaspora. Academically trained as an art historian, Ly employs multidisciplinary methods and theories in her writings, depending on the subject matter.

Karen Tei Yamashita is the author of seven books, including I Hotel (2010), finalist for the National Book Award; Letters to Memory (2017); and her newest, Sansei and Sensibility (2020), all published by Coffee House Press. Recipient of the John Dos Passos Prize for Literature and a United States Artists Ford Foundation fellowship, she is Professor Emerita of Literature and Creative Writing at the University of California, Santa Cruz.