From Art Journal 80, no. 3 (Fall 2021)

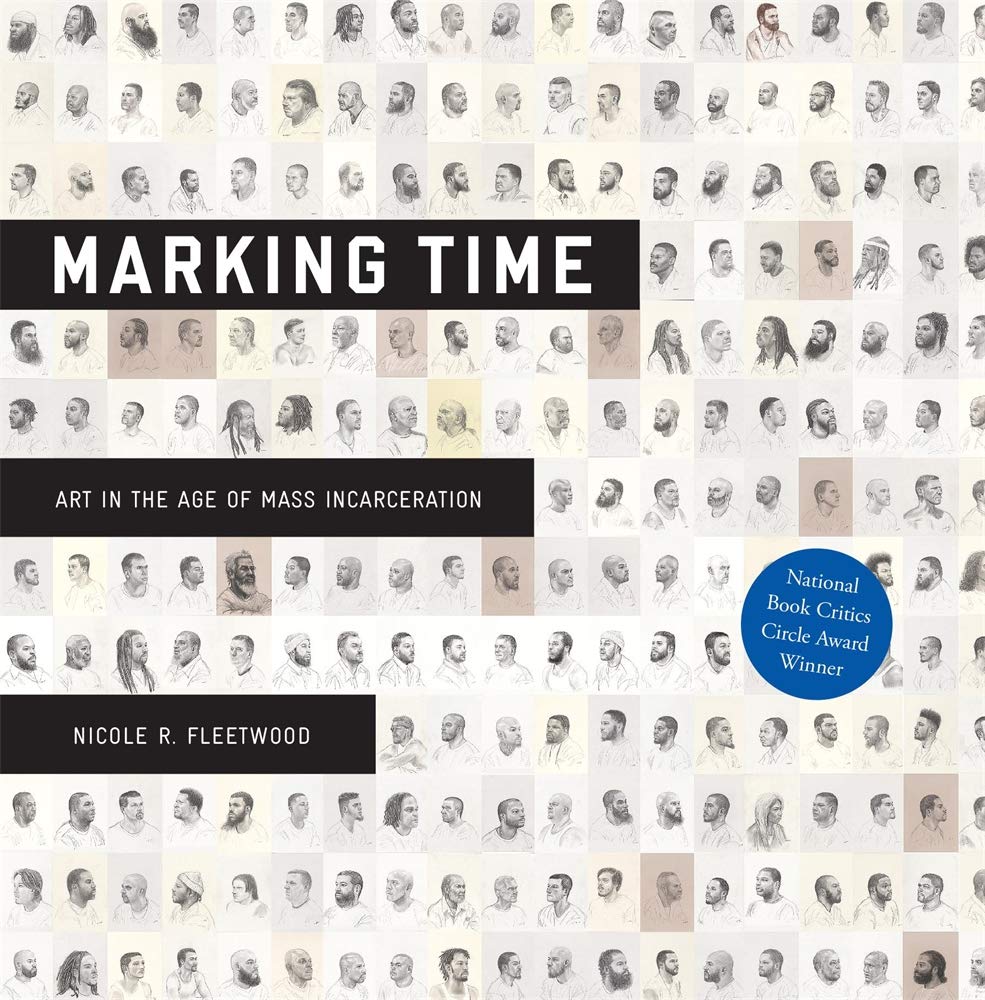

Nicole R. Fleetwood. Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020. 352 pp.; 95 color ills. $39.95

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration. Exhibition organized by Nicole R. Fleetwood. MoMA PS1, Queens, New York, September 17, 2020–April 5, 2021

Marking Time is the shared title of a recent National Book Critics Circle Award–winning publication and an exhibition about prison art. Together, the two offer an extended, innovative model for thinking about the visual culture of mass incarceration and the creative practices of incarcerated artists as well as those who have been touched by the carceral state. From the outset, this approach unsettles the ground upon which more familiar modes of art criticism unfold.1 To talk about one’s approach is to talk about one’s style of intellectual engagement and the social-historical context from which it emerges. There is, of course, no one way of being an art critic these days. And while the book does not intervene in debates between detached observers and those of us more attuned to our relations with art, Marking Time forces all of us to interrogate the notions of freedom, access, and mobility that are foundational to established modes of art criticism, grounded in the idealized image of the self-possessed, discerning critic who gets to determine their relation to their object of study.

The aim of Nicole R. Fleetwood’s project is twofold: she seeks to foreground prison art as central to the contemporary art world and to demonstrate how it emerges as both a manifestation and a critique of the carceral state. She draws on scholarship from Black studies, visual culture studies, and the burgeoning field of critical prison studies to develop a conceptual language for addressing a range of creative practices that arise from conditions of unfreedom. Her approach is deeply informed by a tradition that finds an earlier emanation in the pages of the 1831 slave narrative The History of Mary Prince: “‘To be free is very sweet,’ I said.”2 Prince articulates a knowledge of freedom that, according to Fred Moten, “is highly mediated by deprivation and by mediation itself, and by a vast range of other actions directed toward the eradication of deprivation.”3 The creative practices that Fleetwood addresses in the book bear this knowledge of freedom and are directed toward the dissolution of the punitive captivity that is its condition of emergence.

Fleetwood’s central claim is that “prison art is not simply influenced by but is part of the black radical tradition” (31, emphasis in original). This explains why we hear an echo of Cedric Robinson’s famous assertion that “black radicalism is a negation of Western civilization” in Fleetwood’s conceptualization of “carceral aesthetics,” which frames prison art as a set of creative practices “that do not aim to reproduce or preserve prisons, but to visualize the end of human captivity, devaluation, dispossession, and the carceral logics that tether bodies to penal systems” (26). Rather than serving as a call for the recognition or valorization of “prison art” as a categorical description or for its incorporation into the scholarly lexicon of art history, Marking Time is driven by a broader intervention most starkly conveyed in Fleetwood’s argument that “carceral aesthetics, as relational practices, repositions the viewing and discerning subject away from Western racial hierarchies to create affective possibilities of belonging, collectivity, and subjecthood from positions of unfreedom” (31, emphasis added). This “repositioning” implies a reordering of the visual field, a reconstruction of the very grounds of aesthetic discernment, and a reconception of the practice of art criticism—which is to say, more generally, what it means to think with and among other persons and things. This key aspect of carceral aesthetics cannot be confused with the postmodernist trope of “decentering of the subject,” which merely evacuated difference in the service of reproducing the universalizing discourse that this seemingly radical gesture sought to renounce. Rather, repositioning entails something like seeing the white cube not as a timeless space or an ideological construct but as what it is: a node embedded in an expansive landscape shaped by punitive captivity, racial violence, and the mass removal of millions of people from public life.4

Marking Time examines artworks and creative experiments by incarcerated artists as well as their collaborative projects with nonincarcerated artists, who use their craft to explore the carceral state’s expansive reach beyond prison walls. The book opens with a preface and a note on method that underline the Black feminist conception of relationality at the heart of Fleetwood’s project.5 The practices of care, regard, and mutual support through which Black women continue to sustain intimate and social bonds under the terror and duress of mass incarceration provide Fleetwood with a blueprint for navigating the numerous institutional, logistical, and physical barriers that limit access to incarcerated artists and relegate incarcerated people outside of the view of the public. “This power to reveal and hide prisons and the imprisoned,” Fleetwood writes, “has an enormous influence on how the larger public comes to understand the function of the prison and to justify the removal and incapacitation of millions” (15). Confronted with the carceral state’s control of the field of vision (i.e., “carceral visuality,” 87), Fleetwood relied on networks of currently and formerly incarcerated artists, activists, educators, attorneys, and family members to access the art she studies. From the outset, this approach to prison art as a fundamentally collaborative endeavor runs in conflict with the image of the art critic as a free, singular being unencumbered by the material conditions of thought. What accompanies and animates the many contributions Marking Time makes to art history, Black studies, and visual studies is an intellectual style that proceeds by way of thinking with others.

Each chapter explores different genres, forms, and practices of art making that emerge from imprisonment while explicating the historical, political, economic, cultural, social, and psychic dimensions of punitive captivity that incarcerated artists bring into view. Fleetwood’s illuminating analysis of Ronnie Goodman’s 2008 self-portrait San Quentin Arts in Corrections Art Studio in the introduction to the book effectively demonstrates her sophisticated engagement with the material, compositional, and formal dimensions of works of art, then moves on to considerations of the carceral logics that justify the warehousing of people in prisons, severing of intimate and familial bonds, ongoing decimation of communities, and stigmatizing of entire lifeworlds. For Fleetwood, Goodman’s depiction of a solitary figure looking at a print while standing in a large workspace is an “act of self-invention in which Goodman inserts himself into a studio art tradition” (1). The high ceiling and open floor plan, along with the portraits, prints, and landscape paintings displayed on the wall in the immediate background, depict “an idyllic scene for the creation of art” that stands in stark contrast to the small cells in which Goodman and other incarcerated people are confined (1). Similarly, the fine details of Todd (Hyung-Rae) Tarselli’s realist portrayal of a chipmunk painted on a maple leaf reflects incarcerated artists’ limited access to art materials and serves as a testament to his dedicated practice of painting and drawing nature scenes during his years in solitary confinement. Through this and other forms of prison art we gain access, if only speculatively, to the creative experiments and practices of living forged amid the quotidian violence of the carceral system.

In chapter 1, Fleetwood develops her concept of carceral aesthetics as “the production of art under the conditions of unfreedom” and introduces the related concepts of penal space, time, and matter (25). Turning to the work of theorists like Kandice Chuh, David Lloyd, Jacques Rancière, and Fred Moten, Fleetwood draws attention to how associations of aesthetics, freedom, and subjecthood in Western thought are at the foundation of the racializing discourse and systems of classification that legitimate state power and empire. From the perspective of the regulative discourse on the aesthetic formulated by Immanuel Kant, the incarcerated artist is categorically impossible. “For Kant,” as Fleetwood explains, “the mobile and discerning observer, the man of freedom, is the progenitor of aesthetic discernment and valuation” (29). Russell Craig’s 2013 painting State ID featured in this chapter poses a direct challenge to Kant’s policing of creative capacities, as this enlarged version of his prison ID “reconstitut[es] his criminal index as a portrait of an emerging artist” (25). Craig’s appropriation of his ID as a technology of surveillance and an assertion of a creative capacity that emerges out of a state of punitive captivity not only moves against philosophical discourses on aesthetics foundational to Western thought but also repositions the viewing/discerning subject that those discourses imagine within the “carceral geographies”—to borrow a term from one of Fleetwood’s main interlocutors, Ruth Wilson Gilmore—that leave no corner of the United States untouched.

Chapter 2 reads as robust engagement with the third term in Fleetwood’s triangulation of penal space, time, and matter. Penal space refers to the myriad ways prisons regulate contact and intimacy, within as well as beyond the built environment, while penal time “encompasses the multiple temporalities that impact the lives of the incarcerated and their loved ones” (39). Penal matter at once encapsulates (1) the material infrastructures of the penal system, (2) the regulation of the incarcerated artist’s access to material and supplies, and (3) the body in punitive captivity. In addition to the use of found objects and ephemera, the chapter details how artists acquire and repurpose state goods as part of their art-making process despite the personal risk of being charged with a disciplinary infraction. Fleetwood takes up the language of “mushfake” and “procurement” to describe how artists like Dean Gillispie and Daniel McCarthy Clifford transform penal matter into art. “Mushfake,” Fleetwood explains, “is a type of bricolage in which imprisoned artists reinvent penal matter to create possibilities and experiences connected to their lives outside prison” (64). Gillispie’s mini replicas of a diner and a 1960s Airstream camper are constructed from refashioned discarded objects and items usually found in commissaries, such as soda cans, backs of notebooks, and foil wrappers from cigarette packs. His intricate details often gesture to an elsewhere, like the handwritten sign on the door of the camper that reads “Closed/Gone fishing,” which Fleetwood aptly reads as “gesturing to life off the grid, leisure, and an unboundedness unavailable to those held in punitive captivity” (68). Clifford’s One Ton Ježek (2018), a large “anti-monument” that rests on an angle like a toy jack, highlights the entanglements between militarism and the prison industrial complex, as the food trays stacked inside the sculpture’s large metal frame originate from two facilities that imprisoned political activists and dissenters in World War I. The latter half of the chapter demonstrates how the repurposing of state goods for art making oftentimes depends on and facilitates relationships between the incarcerated. Here, Fleetwood turns to the multiracial Fairton Collective, consisting of Gilberto Rivera, Jesse Krimes, and Jared Owens, as an example, describing the shared interest in conceptual art and abstract painting that they cultivated among themselves. This investment in each other’s artistic development not only is reflected in some of the themes, techniques, and repurposed materials that appear across their works but also is central to how Rivera came to understand his frequent, punitive transfers coordinated by prison authorities as opportunities to access supplies and acquire new art skills. Together, these stories of appropriating, repurposing, and refashioning one’s own status as state goods complicate the prevailing narrative of found objects and ephemera in contemporary art. The unrealized creativity usually attributed to raw materials awaiting the genius of artists is impossible to distinguish from the creative capacities of incarcerated artists, which are devalued as “lawless” and, as such, never waiting to be found.

Chapters 3 and 4 focus on two prevalent visual forms in prisons: photography and portraiture. Noting photography’s extensive career as a technology of surveillance and tool of state power, Fleetwood offers examples of photo studies that attempt to counteract the criminal index represented by mug shots and prison ID cards. Projects such as Sara Bennett’s Life After Life in Prison: The Bedroom Project (2017–19), which consists of photographs of women’s bedrooms after their release from prison, and Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick’s collaborations, focusing on those affected by the penal system in Louisiana, work in traditions of documentary photography to capture the diffuse reach of the carceral state. Fleetwood also notes how imprisonment shapes the constant negotiation between the photographed subject and the photographer interested in documenting their captivity or the continued effects of incarceration. In light of the few examples of photography programs in prisons that depart from rehabilitative models, Fleetwood’s earlier discussion of Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter’s video triptych Ain’t I a Woman (2018) represents the possibilities of experimental video art. The piece shifts between a restaging of the artist’s giving birth in captivity to images of public schools and neighborhoods where she once lived, with lyrical overlays that evoke the Middle Passage, linking the memory of slavery to mass incarceration and what Fleetwood terms as the “afterlives of captivity,” in which many remain tethered by carceral governance and under the stigma of criminality (39).

Alternatively, portraiture, as Fleetwood explains, “counterpose[s] against the large state archive of mug shots and criminal indexes” (124). One of the most common forms of art making inside prisons, portraiture exists as an entry point for aspiring incarcerated artists, a form of currency, and a way of visualizing kinship and intimate bonds disrupted by the carceral state. Mark Loughney’s Pyrrhic Defeat: A Visual Study of Mass Incarceration (2014–present) serially deploys the genre’s venerating effects with his drawings of the hundreds of people housed with him in a Pennsylvania prison facility. This ongoing project conveys the burgeoning numbers of people locked away in prisons and responds to how prisons deeply shape the visual field.

I lifted the title of this review from the second line of A. B. Spellman’s “When Black People Are,” featured in the 1971 anthology The Black Poets, edited by the famed Dudley Randall. When they appear on the other side of the break that opens the poem—“when black people are/with each other”—the three words convey a relational mode that is untethered to any particular subject. This mode returns at the poem’s end, which describes a collective survival in which “strength flows/back & forth between us like/borrowed breath.”6 It is difficult to square the interdependency and conspiratorial quality of that “borrowed breath” with Spellman’s letter to the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) ten years later as the director of the National Endowment for the Arts’s expansion program, which Fleetwood quotes in chapter 5. Rejecting the coalition’s request for the continued funding of BECC’s Prison Arts Program, a regretful Spellman cites the shifts in funding policies under the Reagan administration with a sentiment that conveys the complex power structures, dynamics, and “fraught imaginaries” that prison arts programs and collaborations between incarcerated and nonincarcerated artists have been forced to maneuver (158). Fleetwood’s discussion of political prisoner Ojore Lutalo’s art-making practice in solitary confinement in chapter 6 speaks to the afterlife of Spellman’s earlier radical vision of Black solidarity. These mostly black-and-white collages, which the artist describes as “visual propaganda” in allusion to Emory Douglas’s political aesthetics, record the isolation, sensory deprivation, and disorientation that he endured while segregated from the general prison population for the infraction of allegedly promoting radical political ideas. Consisting of cuttings from newspapers and legal documents, these collages were at times correspondences with nonincarcerated people and constructed a “provisional public” advocating for his release across carceral geographies (25, 214)

In the final chapter of the book, Fleetwood offers parts of her own experience of visiting family members in prison as an autobiographical example of the power of vernacular prison portraits to visualize attachments between the incarcerated and their nonincarcerated loved ones across time and space. In addition to the distinctive backdrops of these portraits, which both signal and conceal the carceral setting, the photographs’ composition, circulation, and haptic qualities enable practices of belonging, rendering them into complex artifacts that mark the different ways those inside and outside prison experience the passage of time. Through her story, Fleetwood offers an instructive account of the “event of photography,” with descriptions of how the staging of a photo shoot creates a site where posers can potentially find small, intimate moments of contact while following a photographer’s direction.7 Under conditions of unfreedom, the touch of the photograph, the touch that photography enables across penal time, space, and matter, radically pronounces an affectively charged domain where the intimate ties severed by the carceral state intermingle and congeal into emblems from another world, where prisons have ceased to exist.

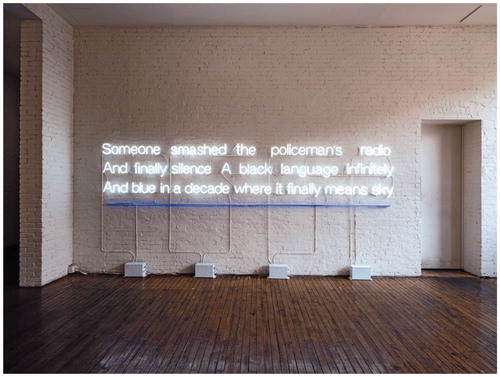

The book ends where the MoMA PS1 exhibition begins—with the thought-provoking work of interdisciplinary artist and writer Sable Elyse Smith. Fleetwood’s conclusion focuses on the ways Smith, who has spent much of her life visiting her father in prison, uses her art to “highligh[t] both the disruption that prison causes for black family life and social identity, and the intimacies of gendered and sexual formation in the diaphanous and highly regulated lenses of carceral visuality” (257). Affixed to one of the white brick walls in the foyer of the MoMA PS1 main building, Smith’s Landscape V (2020) was the first piece that visitors encountered. The title of this neon-text work alludes to the Western tradition of landscape paintings while at the same time recalling the prison visiting rooms where paintings of dreamlike vistas serve as the backdrops against which the incarcerated pose for photographs with family and friends. From the outset of the exhibition, the repositioning that Fleetwood theorizes in her text was already underway, as Smith marked the convergence of these two white cubes—the prison visiting room and the exhibition space—with neon-lighting tubes bent and arranged to spell out a poetic vision of abolition that plays on the level of the senses:

Smith attunes the viewer to what the sound of the police, as carceral visuality’s corollary and accompaniment, seeks to drown out: a knowledge highly mediated by the conditions of unfreedom from which it emerges. To embrace this knowledge is to realize that one is embedded within a landscape shaped by punitive captivity, racial violence, and the mass extraction of millions. It is this repositioning that animates Fleetwood’s book, her curatorial sensibility, and her intellectual style. Her project invites viewers of prison art to follow the approach of the visitor, a style of thinking and being known well by those of us familiar with the touch of carcerality.8

Ultimately, this last note is one of gratitude. I have never written about prisons or shaken the intellectual isolation engendered by the particular stigma I am describing as the touch of carcerality. The gift Fleetwood gives is the acknowledgment that many of us visitors—those of us who know the number five as a shibboleth—are already here, with each other. I have to also thank Devon Wade, Amanda Alexander, and Julia Mendoza, along with my students and friends who have taught me what it means to be a visitor.

Nijah Cunningham is an assistant professor of English at Hunter College, CUNY. His teaching and research focus on African American and African diaspora literatures and culture. His writing has appeared in platforms such as Small Axe, the New Inquiry, ASAP/J, and PMLA, and he has a forthcoming catalog essay for Samuel Levi Jones and a book project titled “Quiet Dawn.” He is the curator of Hold: A Meditation on Black Aesthetics (Princeton University Art Museum, 2017–18) and, alongside David Scott and Erica Moiah James, cocurator of Caribbean Queer Visualities (Small Axe Project, 2016) and The Visual Life of Social Affliction (Small Axe Project, 2019–20).

- For Nicole R. Fleetwood’s brilliant reflections on the question of approach, see “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration Book Launch,” featuring Fleetwood, Fred Moten, Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter, and Jesse Krimes, MoMA PS1, April 28, 2020, Vimeo video, https://vimeo.com/416021133.

- Mary Prince, The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, Related by Herself, with a Supplement by the Editor (1831), reprinted in The Classic Slave Narratives, ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. (New York: New American Library, 1987), 208.

- Fred Moten, “Knowledge of Freedom,” CR: The New Centennial Review 4, no. 2 (Fall 2004): 303.

- This assertion is my attempt to at least gesture toward some of the burning questions that Marking Time has engendered in me as a reader. And while it may go beyond the scope of a book review, one of these questions should at the very least be put in the air: Is the contemporary art world—as well as art criticism and art history—capable, ready, or willing to approach prison art?

- In her thoughtful review of Marking Time, Jackie Wang rightfully states, “It is important to remember that the seeds of the police and prison abolitionist movement were planted long ago, as far back as the struggle to end slavery. In recent decades, Black women have tended these seeds by developing the conceptual framework for the movement (think Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Mariame Kaba) and by performing the care labor of holding together communities that have been convulsed by mass incarceration.” Fleetwood’s work is an extension of this ongoing struggle for Black freedom from plantation slavery to the contemporary carceral state. See Wang, “Carceral Aesthetics: The Conditions of Making Art in Prison,” Art in America, June 18, 2020, https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/marking-time-art-age-mass-incarceration-nicole-r-fleetwood-prison-1202691575/.

- A. B. Spellman, “When Black People Are,” in The Black Poets: A New Anthology, ed. Dudley Randall (New York: Bantam Press, 1971).

- See Ariella Azoulay, Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography (London: Verso Books, 2012).

- See United States v. Casas, 356 F.3d 104 (1st. Cir. 2004), US App. LEXIS 763 (2004). Citing my father’s case poses a profound epistemological challenge that I cannot begin to unravel here.