Advice to a Young Black Artist

Howardena Pindell

I am a bit of a dinosaur. I remember the Civil Rights Movement, and when segregation and Jim Crow Laws were in full force in the South. Unfortunately, the North was not much better. I was the only African American in my BFA class at Boston University, and even that made some people uncomfortable. One student’s father went so far as to offer the school money to get rid of me, because he did not want his daughter to be in class with a Black person. Even years later, if a white dealer brought a Black artist into their gallery, fellow dealers would warn them that they were putting off their white clientele. Over the decades, I’ve learned to watch my back, and to be wary of attempts to rob me of my dignity, or my identity as an artist.

Art world shenanigans take many different forms. I have had dealers who have stolen my money. I have had dealers refuse to return my work. I have had dealers ask for exclusive representation while refusing to list me as one of their artists. (This was especially common in the ’70s when the work of artists of color was literally kept in the closet, unlisted and out of view.)

When I was a MoMA employee during the ’60s and ’70s, a New York art dealer gifted a complicated work on paper to the museum—receiving a tax write-off in return. The artist wrote to the museum saying that if the work was displayed, he’d personally come to the museum and take it off the wall. It was his property, and he was never paid for it. To the museum’s credit, they removed the work from the collection and probably returned it to the artist.

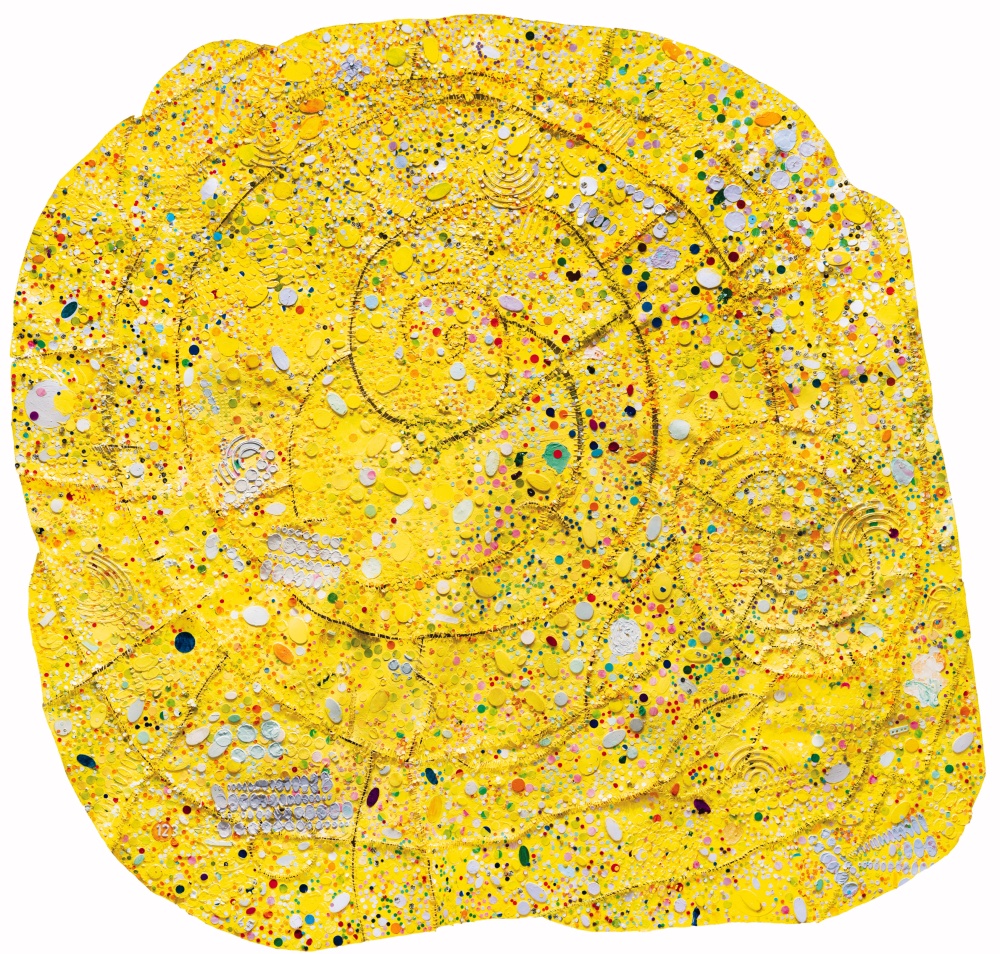

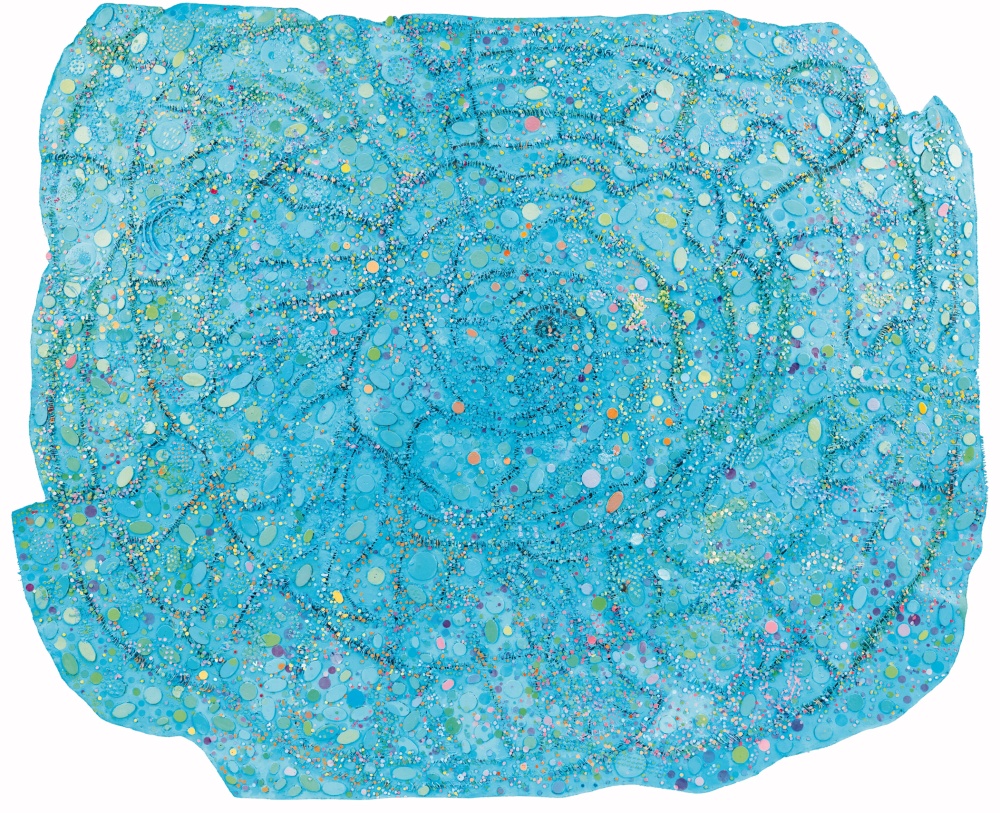

Years ago, when I started speaking out about racism in the art world, I was removed from a show and began receiving harassing phone calls. My more political works were mocked as “shrill.” My abstract works, particularly ones that included glitter, were trivialized. One white male critic for the New Art Examiner said that he wanted to have sex under my paintings.

Museums were not interested in issues of racism, homophobia, or sexism either, and they were particularly unmoved by the abstract work of women and nonwhite artists. Sadly, when white women rose to positions of power, most were just as bad. The white feminist movement made a point of neglecting issues of race. I keep promising myself to write this all down in a memoir before my memory goes off the rails.

In a lot of ways, though, things are better than they were in the past. I’ve finally found a dealer I can trust who actually pays me! His staff is also very supportive. The art world, in general, is more supportive. Ann Temkin, the new chief curator of the MoMA, has successfully integrated the collection, placing the works of the African American sculptor Mel Edwards in the same room as those of Jackie Winsor. (When I recommended Edwards while serving on an NEA committee in the Virgin Islands decades ago, the committee chairman just said, “We’ll have none of that!”) Jack Shainman Gallery now represents more than thirteen African and African American artists. My own, Garth Greenan Gallery, now represents eight Native American artists. That was unheard of in the ’60s, and probably even in the ’90s.

Perhaps most importantly, your generation now has the tools to support each other. You and your fellow artists can warn each other on social media about abusive dealers, institutions, and practices in ways far more powerful and far-reaching than telephone calls, snail mail, and word of mouth.

With all that in mind, here are some simple pieces of advice from one artist to another:

- Whenever lending art to a dealer or art consultant, protect yourself with a consignment agreement. It should be signed and dated by both of you. Agree on the amount of time they can hold the work. Make sure they have insurance.

- Be wary of private dealers. They frequently borrow work without returning it. If you do not have a formal arrangement with someone, do not let them mediate someone else’s purchase of your work. Unless you have a formal contract, let them bring the interested buyers to your work, and not the other way around.

- Keep high-quality images of your work. Remember that digital media is not archival. Keep a physical backup.

- Document your works’ locations. In the old days, I’d use large format index cards and note the title, date, medium, size, and, if sold, to whom. Write down the buyer’s contact information. Also list any exhibitions the work has been in, as well as noting if it sold through a particular exhibition.

- Use archival materials. Do not hang works in direct sun as it will bleach some materials. While working in a museum for twelve years, I watched some works deteriorate in real time.

- Keep in touch with dealers and individuals who hold your work, particularly if they don’t have a gallery.

- Keep your CV updated. It’s not only useful when communicating with dealers, galleries, collectors, press, and museums, it’s an important record that can protect against people taking credit for your ideas.

- If you sell your work, make sure the sale is documented with artwork details, price, date, and contact information of the collector. Keep copies of these invoices for your tax records.

A number of African American artists and I were approached by a private dealer who took our work. He’d periodically send us small amounts of money then, one day, disappeared with all of our work. He was never heard from again. A different white dealer, who was always bad about paying us for our work but who was otherwise very nice, killed himself out of the blue, just two weeks before my show. He’d recently purchased a Maserati and presumably had been overwhelmed by debt. His wife returned our work and tried to pay us, which was a nice gesture for a woman in such a difficult position. She could have just as easily decided to use our work to pay off their debts.

Finally, be cautious about who you let in your studio. They may be grazing for ideas, knowing that they will have an easier time getting the work out. The comedian Jerry Lewis would go to African American comedians’ shows and would steal their material. White art historians have done similar things to Black art historians. A white woman artist I knew—who was dating a famous white male artist at the time, and so had an easier time getting exhibitions—did this to another white woman artist after visiting her studio. It broke the other artist’s heart and she moved out of New York. It was particularly painful as they were both involved in the women’s movement.

While the art world has come a long way, I know you will still face many challenges. I don’t highlight these problems to discourage you, but to prepare you. If I could make it through all those barriers, so can you. Art world “scams’’ will continue to evolve, but your generation of artists can use social media to warn each other and work together. Most importantly, never give up!

Born in Philadelphia in 1943, Howardena Pindell studied painting at Boston University and Yale University. After graduating, she accepted a job at the Museum of Modern Art, where she worked for twelve years, finishing her tenure there as an associate curator and acting director in the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books. In 1979 she began teaching at the State University of New York, Stony Brook, where she is now a Distinguished Professor. Throughout her career, Pindell has exhibited extensively. Most recently, her work appeared in We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–1985 (Brooklyn Museum, 2017). Her 2018 retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, titled Howardena Pindell: What Remains to Be Seen, traveled to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (2018) and the Rose Art Museum (2019). Pindell’s work is in the permanent collections of major museums internationally, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen, among many others.