Advice for the Young Artist

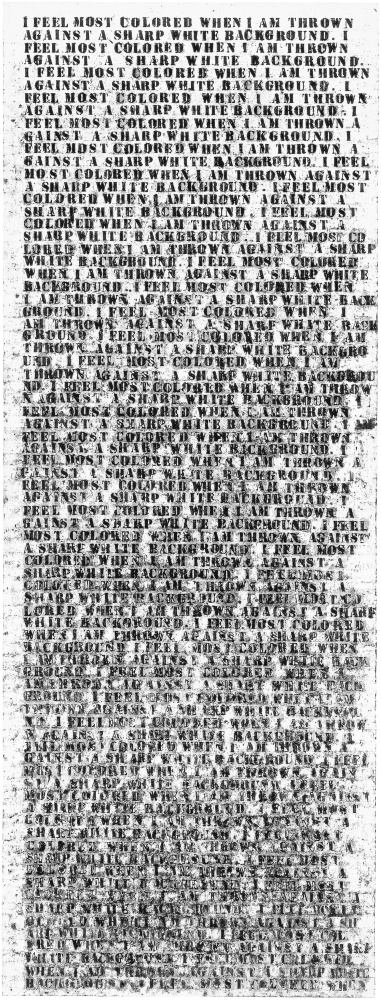

Glenn Ligon

Things people have said to me:

“Ninety-nine percent of your success is because you are Black,” said a fellow artist.

“Oh, you’re the guy that makes that kindergarten art with the letters in it,” said the prominent art critic.

“Our director can’t imagine one of your neons in the lobby,” said the curator on why my neon couldn’t be installed in the lobby of the art museum where I was having a retrospective.

“We only collect local artists. We are not interested in anything social or political,” said the collectors who hosted the dinner after the opening of my retrospective.

“I see they have you tap dancing for your supper,” said the director of an art museum when he heard I was being honored at another museum’s gala.

“Strange that three men were asked to give speeches at this gala honoring three women artists, but you’re Black and gay, so I guess that’s OK,” said the host of the gala table I was sitting at.

“You must not be interested in any of this!” said the collector who had only shown me work by the white artists in her collection. (She then brought me into the kitchen where the work of an important Black woman photographer was hung.)

“We only collect black artists. We don’t know why,” said the white collectors who only collect Black artists.

“I wish I had bought your work sooner. You’re out of my price range now,” said the multimillionaire.

“We’re not sure why you are leaving the gallery. We did all we could for you,” said the dealers whose gallery I left because they thought they had done all they could for me.

“Why is your work so serious?” asked the owner of a gallery where I was having a show.

“We are just not interested in Black people anymore,” said an audience member after a talk at Princeton University.

Folks is crazy. I wish I could say that it gets better the further along you are in your career, but I would be lying. When you have a bit of success, they will find more subtle and creative ways to work your nerves. Keep the focus on doing your work. The rest is noise.

Here’s some advice—hope it helps:

Dealers are not your friends, they’re your business partners. Your friends don’t take 50 percent of your money.

Just because you can sell a piece doesn’t mean you should. Hold back the work that feels important and generative for future directions in your practice.

A booth at an art fair is not a “show.”

Collectors collect your work for all sorts of reasons—some of them are fucked up.

If a collector is in your studio and wants to buy everything, don’t let them: They are just trying to get stuff at wholesale prices.

The small stuff matters. Don’t compromise.

The cliché is true: you have to be twice as good just to get half as much.

Be a little hard at the beginning so they are scared and treat you with the respect you deserve. You can always be nice later on.

Find those curators and writers that love and understand your practice and stick with them.

The idiot curator that hung your work upside down in that group show might end up running a museum. Remember that before you totally curse them out.

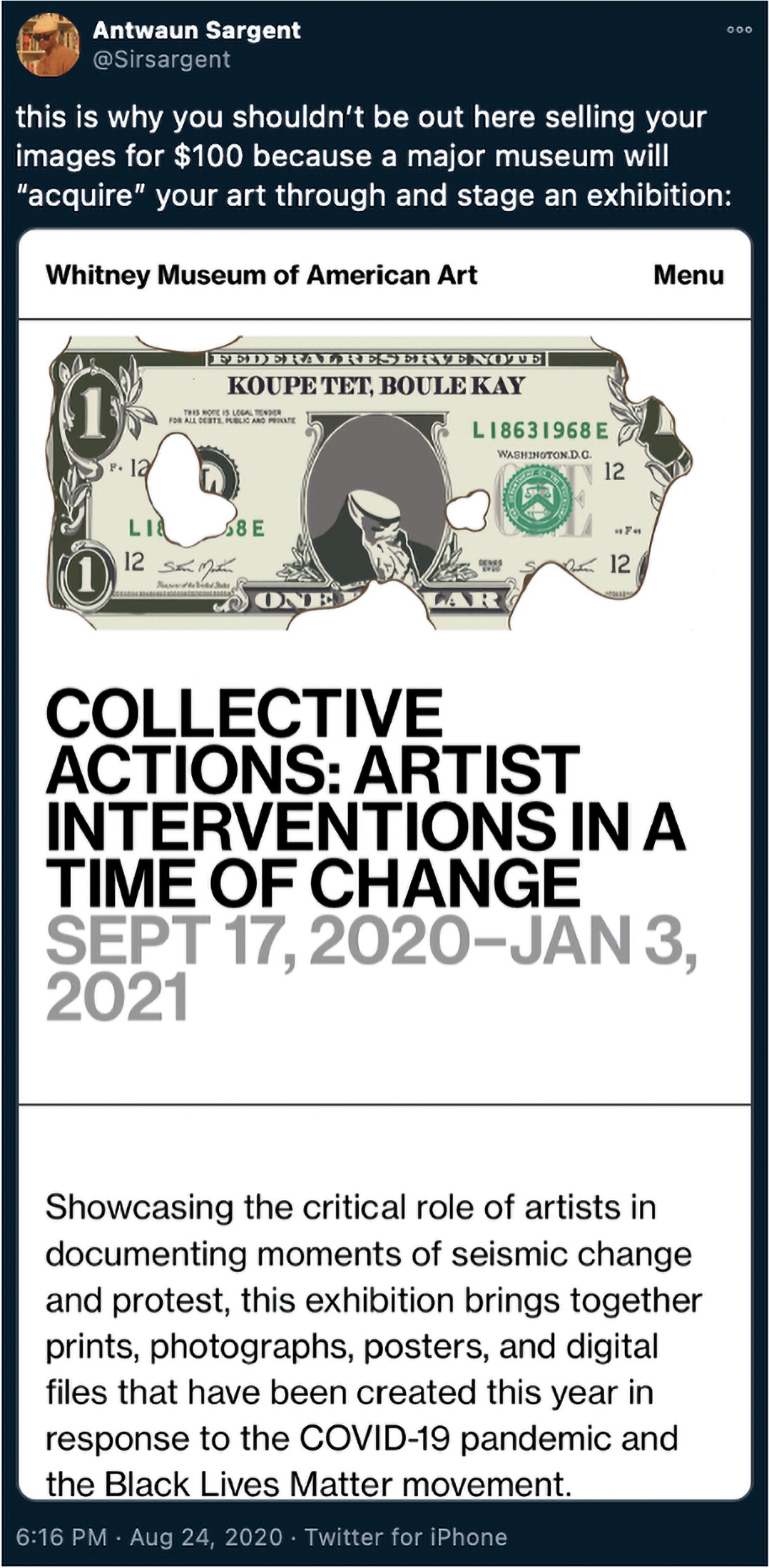

Just because a curator has shown no interest in your work doesn’t mean they won’t ask you to do something to make them look good.

Be careful who you give artwork to—you might see those gifts up at auction years later.

Other artists generally have your back. But sometimes they will stab you in it.

Your time is precious. If someone is asking you to be on a board, participate in a panel discussion, or judge a prize, you better want to do it.

If someone asks you to help them create a program to increase diversity in their institution, tell them, “You don’t have to start a new program to engage women, trans people, and artists of color. You already have one. It’s called the exhibition program.”

Museums and galleries aren’t doing you a favor by showing your work.

Finally, some wisdom from the late curator and writer Okwui Enwezor, appropriate for use in many situations: “‘No’ is a complete sentence. You just have to put a period at the end of it.”

Glenn Ligon (b. 1960) is an artist living and working in New York. Throughout his career, Ligon has pursued an incisive exploration of American history, literature, and society across bodies of work that build critically on the legacies of modern painting and conceptual art.