Conversations is a series of critical dialogues between artists, designers, historians, critics, and curators on timely issues in the field.

Rebecca Zorach and Mechtild Widrich share interests in public art and activism that they have had the chance to discuss on various occasions in the last few years, on panels and around dinner tables. On the occasion of the publication of Widrich’s new book Monumental Cares: Sites of History and Contemporary Art, which came out in spring 2023 from Manchester University Press, they sat down for a chat over coffee. Then they began writing an online dialogue that grew to encompass questions of experience and mediation, whether models of care need to irritate, current politics of public space in the city of Chicago, and the interdisciplinarity of these inquiries. How do we think about the current specificities of public art practices between embodied performance, architecture and urban space, and the digital realm? And what do new ways of memorializing have to do with the fall of old monuments and old regimes?

Rebecca Zorach: Reading your book, I’m thinking about recent transformations in how we think about place and its relationship to history, embodiment, and performance. When I think back over the past twenty years, the growing role of social media in how artworks (static or performative) circulate seems pretty decisive. “Public” space was always fraught, but our use of it now doesn’t feel the same as it did in the early 2000s. In 2007 I cocurated a project called Pathogeographies: Or, Other People’s Baggage with Feel Tank Chicago (principally with Mary Patten) that involved all kinds of performances in public space—they were documented, the images were put up on the exhibition website, but there wasn’t the same sense of circulation in Instagram or otherwise. There might have been a Tumblr. But now, it’s as if those projects never happened! At the same time, there was something different about creating a performance that was really for the people who were there. It might be a microaction, but with a different intensity. I was struck by the changes wrought by social media; you also allude to the changes in people’s relationship to public space forced by COVID-19 restrictions, and that seems to go in a similar direction. Many of us lost the habit of public space for a while, whether by choice or not.

Emilio Rojas’s The Grass is Always Greener and/or twice stolen land, 2014 (image provided by the artist)

Alexandra Pirici, If You Don’t Want Us, We Want You, 2011 (photograph by Alexandru Patatics; provided by the artist)

So, I’m thinking about the public for public art, and how social media encourages us to identify in all kinds of ways that are not about where we live. (I’m struck right now by the low voter turnout for eighteen-to-twenty-four-year-olds in Chicago’s recent municipal elections: the political forces that shape experience in site-specific ways don’t seem to be registering as all that important to young people. Though they did vote in greater numbers in the run-off and contributed to the progressive candidate’s win!) If, traditionally, when we think about what art has to say about history, we’ve thought about it in ways that are tied to place, what is happening now? When artists make performative interventions in public space, are they really performing in a place, or just against the place as backdrop? In this respect I might contrast Emilio Rojas’s The Grass is Always Greener and/or Twice Stolen Land (as “in” a place) with Alexandra Pirici’s If You Don’t Want Us, We Want You (as “the place as backdrop”). Rojas works with the landscape in a way that engages with the site—with the land and its definition—in a very direct way. It looks to me as if Pirici’s work didn’t necessarily require being at the site in order to engage with it. But is this a false dichotomy? There are hints in your account of what it might have meant, in a physical or affective sense, for the group to be at the site (e.g., the former presence of armed guards).

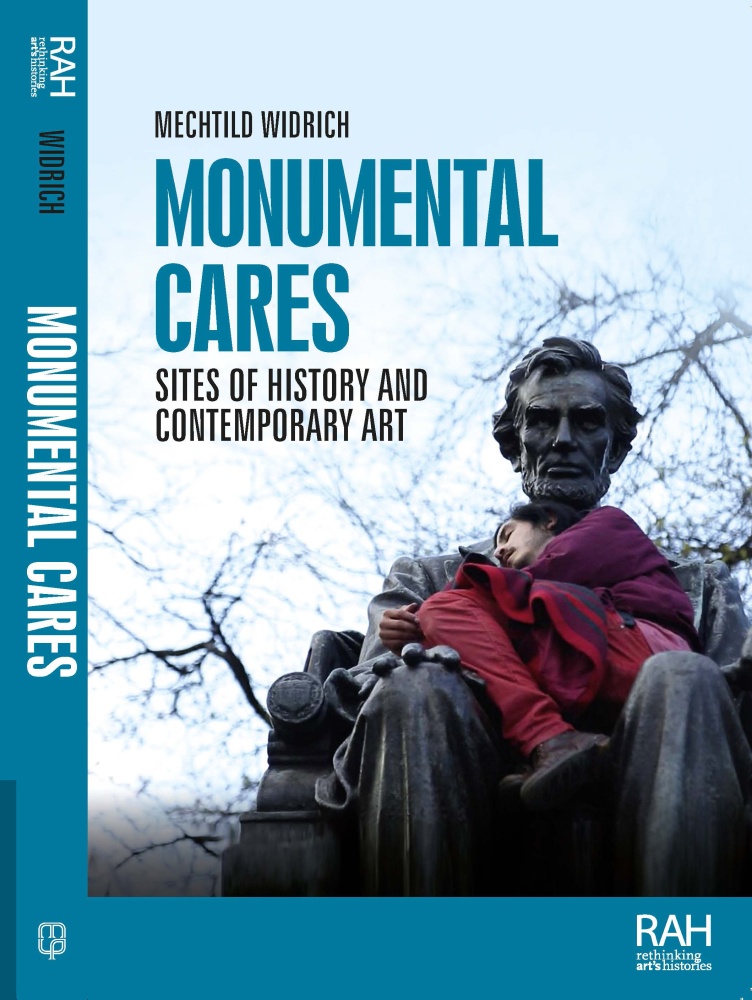

Mechtild Widrich: Thinking about site and place today, as you mention, necessarily includes virtual space and spectators. I think the main difference between these works of Emilio Rojas and Alexandra Pirici is that Pirici’s reacts to a “monument” (Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu’s House of the People, an enormous neoclassical building in Bucharest) visible behind the performers, and Rojas’s asks us to think about unseen history, in a way making it visible: the history of Settler Colonial takeover of land and resources (in this case British Columbia), the changes in the attitude towards nature. As a matter of fact, the two artists also use the opposite strategy: Rojas performing in the arms of one of the most recognizable Chicago monuments, the Lincoln statue (on the cover of my book), and Pirici dancing for the camera on the edge of Bucharest, seen live only by commuters in cars. Here it is mediation, photographic in the first case and then possibly amplified by online dissemination, that allows most of us to even think about the sites and spaces they activate.

It is correct, of course, that Rojas’s video documents a performance of endurance. He told me he estimated the time it would take him to roll and unroll the sod over seven kilometers (over four miles), but was off by a factor of three. The performance took twenty-five hours, his videographer left several times to sleep, his hands started swelling. Pirici uses a whole dance troupe, and carefully chosen cardboard packaging, to intervene. But, because Pirici then circulates the image as a postcard, it has another, pretty physical life. Online uses strike me as physical too! What some people consider dematerialization is really an extension of access: which doesn’t mean it’s always easy or to be celebrated . . . we often look superficially at what’s on our phone, but this is not a necessity.

RZ: Right, I’m not questioning whether it has a physical life—I agree that online experience is embodied. But I am asking about how specific places and the embodied experience of them are politicized differently for people who are frequently present in the space (or even made conscious of not being present) and whose lives are shaped by those spaces, or similar spaces. It feels like the engagement is different in these two types of performance. And there are even differences in this respect among the different instances that make up Pirici’s project that are visible in the postcards she made. I’m thinking about how at some point it seemed imaginable to think about public, site-specific performances as making (even micro-)interventions that addressed specific sites and had the capacity to disrupt the expectations of passersby about what could occur in public space. Now it feels like in many cases (and for many reasons) there aren’t passersby, or the space is so heavily policed that it’s dangerous to do anything out of the ordinary. But artists have also always (well, for many decades!) performed for the camera.

MW: Do we differ in that you see a tension in your last sentence (“But artists have also . . . performed for the camera”), and I see a necessary concomitant to the subtle performative interventions?

In my earlier work I showed how careful documentation can provide access to what you call microinterventions, and thus turn ephemeral acts into more lasting ones.1 In Monumental Cares, I connect this with recent returns to terms that have long been held in suspicion, transparency and realism. Transparency can seem very literal, even as a metaphor, related to the lens, to mediation, and the moment a space is transported into a different medium. Pairing it with realism allows for a productive distortion, where the mechanism through which we see is taken into account, so we see (as it were) both it and its subject. Realism does not mean that artists have privileged access to what is “real” (or authentic), but that artists reflect on conditions in the world, be it history, social tensions, marginalization, etc. I discuss Honoré Daumier’s lithograph of the Rue Transnonain as work of realism at the intersection of activism and commemoration, and its circulation in print journalism. Where is the space in question? Is it the one that is shown in the work, the aftermath of a deadly intrusion of the national guard into a private home? Or the space of the magazine that distributed the lithograph to its subscribers? I discuss Ai Weiwei’s film CoroNation and Catherine Opie’s The Modernist in similar terms, because they use media self-consciously to reflect on the world, getting to the general through very specific, even eccentric spaces. Returning to your point, the mediated space will never be identical to the lived one: but the gaps, if one is aware of them, can add to the depth of the engagement.

RZ: Chicago, the city we both live in, has numerous early twentieth-century monuments that tell a certain (white, male, settler colonial) story of history, and more recent public artworks that seem to operate along the lines of Miwon Kwon’s “community of mythic unity” (even if I would argue that the work she coined that phrase to describe, Suzanne Lacy’s Full Circle, doesn’t fit the description so neatly).2 We don’t have a lot of physical memorials or monuments that really contend in an intentional way with traumatic political histories (of course we have some that perform those histories in retraumatizing way). We do have the recent Chicago Monuments Project, a group commissioned by the former mayor to produce a report confronting some of the problematic older monuments. The group’s report also expressed optimism about the possibility that new public artworks—as well as reframings of some of the older works that can’t be removed—might result from the conversations they have tried to spark.3 Certainly there have been performances that intervene in these questions. I’m thinking of the “Whose Lakefront?” project, a performance that reminded us that Chicago sits on Native land and that, in fact, the Potawatomi have staked a well-founded (if not yet successful) legal claim to much of the city’s lakefront.4 but how does the brief temporality of the performance contend with the rhetoric of permanence of the monumental?

MW: Chicago reinvented itself in the early twentieth century with an urban plan inspired by Paris, as a European city on the Plains. I am currently working on two monumental equestrian statues, The Bowman and the Spearman, in the center of Chicago framing the lakefront. Depicting naked native Americans on horses, they were produced in the 1920s by Ivan Mestrović, a Croatian artist. He reached back to a repertoire of Slavic heroes; for the Chicago commissioner (the Ferguson Fund of the Art Institute), the concept of a “vanished race” at a time when the vicissitudes of the reservation system triggered protest, and an unprecedented rigorous study of the Native American social situation, the Meriam Report (The Problem of Indian Administration), 1928. The monument was perfect to render such tensions “invisible” while evoking romantic clichés. This is, understandably, one of the monuments that the Chicago Commission from the Chicago Monuments Project would like to see contextualized, a position I heartily endorse. Of course, there is “mythic unity” at work here, but also mythic conflict, mythic decline, and so on. What I find interesting, as you yourself hint in not fully agreeing with the critique of Suzanne Lacy, is how public art intervenes in mythic thinking, even if only as an irritant, getting people who argue about a monument or its subject to study the history or issue represented.

I’m a strong believer that art has to get us to seek such deeper engagement to history, rather than being able to deliver it through some avant-garde formula, like being “agonistic.”

RZ: I completely agree—I think the agonistic formula has embedded in it a certain understanding of who is the audience for art, and it’s not necessarily people who would object to some of these problematic monuments, or who may find them, in fact, incredibly aggressive, and engage in activism to have them removed or reframed. (By the way, Problematic Monuments was the title of a freshman seminar I taught this year! In the end it felt unsuccessful because the issues seemed repetitive, which is another reason I like the real variety of engagements with monumentality by contemporary artists that you study in your book.) At the same time, I think you are (as I am as well) a bit suspicious of sites that appear too seamless—either a romanticization of beautiful nature or the kind of evacuation of the specificity of industrial or corporate sites that you note in Carey Young’s work. Do we want something of an “irritant” role for art, if not an agonistic one?

MW: It is noteworthy that what the eighteenth century wanted from natural environments and aesthetic ones like gardens—the transmuted threat of romantic sublimity—often strikes us as problematic now in a monument, or a critical response to it. Still, I do not attempt to diagnose one universal problem or to isolate an aesthetic effect that always succeeds in monument discourse, because I just don’t think that the variety of needs addressed by monuments will admit of even that much uniformity. It’s not that monumental art isn’t allowed to be beautiful—nor is irritation always unproblematic, as witness the reception of Ai Weiwei’s performance evoking the drowned boy Alan Kurdi.5. I think you have your finger on the issue when you note the divergence of audiences: what is irritating to one group (let us call them the general public) is soothing to another (the art audience who expects agonism). That is one reason I have partly looked beyond the shock tactics of much 1960s performance, inherited from the classical avant-garde, and explore in the book various ethics of care, which need not be sentimental, formless, or moralistic. Also, I think it is part of our job as researchers and writers to open up the discussion around monuments or effective critiques of them, but not to tell everyone what “works” and what “doesn’t.”

In that spirit, you have published on Chicago-based activism in the 1960s6 and are preparing a manuscript that addresses public art here—for me, the two go together naturally, because I am interested in the interaction between art and its audience. In this sense, every monument also needs to be seen from a presentist perspective. Not to occlude its history (I am a very committed historian), but because it will work differently at different moments. How do present concerns inform your own ongoing work on public art and monuments?

RZ: I love your focus on the ethics of care, and this and related questions (how we show care, why we care), are going to continue to inform my thinking on how and why we make monuments and their analogues. I feel like I used to hear a lot more challenges to historical work that was thought to be overly “presentist” and perhaps that doesn’t bother people as much now—I certainly think it’s important to convey history in accurate and responsible ways, but the things we find interesting and important in history have always been conditioned by the urgencies of the present, and I don’t think we should apologize for that. They inform each other. You have to do responsible history to understand the concerns that drove monument campaigns of the past—that helps us better understand and explain why the resulting monuments continue to pose problems today.

My forthcoming book circles around monuments (as yours does) and around Chicago—admittedly, it circles pretty widely, but keeps returning. One of the things this conversation has made me aware of is how much the projects I’m writing about, at least in the second half of my book, are about the absence of human beings—for any number of reasons (murder, displacement, incarceration, violent border regimes). On some level this is baked into the traditional logic of the monument as memorial: we monumentalize people who aren’t there anymore. But we can also ask questions about whether artworks naturalize that absence or not.

MW: It is interesting that you speak about the absence of humans. Commemoration often refers to trauma; it can also be used to initiate concrete amends or healing. History can and should allow a new generation to access the past, in particular if it is traumatic. Some critics think this requires figurative representation of those silenced. I respect that, but cannot always agree that a bronze stand-in for a displaced person, say, provides the most meaningful access to history. I discuss such choices in the book, in connection with Yael Bartana’s Orphan Carousel for instance, which puts emphasis on the absence of play by inviting it, in contrast with figurative statues of displaced or murdered children. The most imaginative work in this sense is often urbanistic in scope.

RZ: The question of figuration can get very complex, but I agree with you that the figuring of absence through absence can be more meaningful than an attempt at recreating those who are missing. Thinking of emptiness, I also found myself—unexpectedly, since it was not really part of my training—addressing architecture and landscape architecture. That also reminds me of one of the things I admire about your book, which is the way you fold questions of architecture as monument into the consideration of sculptural monuments and the performative works that address them both (as in your discussion of the Alexandra Pirici work we mentioned earlier). In the discussion of the removal or reframing of monuments in the US we rarely talk about buildings, though I think a case could be made that there are buildings that should also be subjected to this kind of attention.

MW: I find my training in the architecture department at MIT comes in handy here. I see monuments as objects similar to buildings, occupying space as well as generating images in other media. From there, treating performance photography monumentally was a logical step (as I do in my first book, Performative Monuments). But my interest in spatiality started earlier. My PhD work at MIT helped me understand what I was already trying to do in the master’s thesis on Nancy Spero, thinking about political art in its spatial relations. Spero’s wall pieces of women from different times and places was where my interest in power, sites, and representation started. One nagging question there is how these works function differently—say, on the roof of the hallway of the Harold J. Washington Library [Chicago’s central public library]—than they do on a gallery wall or page. In some ways, “on-site” (on the wall), they are harder to perceive, and are missed by many: so there must be some intended gain, a function of spatial experience, motivating them.

In Monumental Cares, I try to even go beyond buildings: I introduce geographical thinking, informed by the radical geography of the 1970s. The shifting and malleable constructions that comprise real territory or sites, their imagination and representations in various media can be seen through a geographical lens, one including different temporalities and spatial scales. It also opens up the discussion of natural resources and their depletion, an important but daunting task. I had to wrestle with that for a long time. A short book, a pamphlet really, by Kathryn Yussof, A Billion Black Anthropocenes Or None (2018) allowed me to first see that. How to get from the monument debate to climate change? It’s not just a matter of representing the latter, notoriously an amorphous process, but of the very labor and energy-intensive materials (stone, steel, bronze) and the maintenance they require. Extracting recklessly and constructing celebratory history denying the damage to humans and the planet emerged as obvious partners in crime.

Like you, I think reflection on the current condition needs to be figured into our making of history through objects. But that makes alternative solutions more pressing, rather than requiring us to lapse into silence.

RZ: The question of materials and their sourcing is part of what makes the Doris Salcedo work you discuss in your conclusion so compelling, where the act of recycling materials is itself part of the point of a memorialization process that is as much about the future as about the past. But that project also makes me wonder about the point you make at the very end of the conclusion. I love the idea of multiple non-competing ways of understanding and inhabiting the world. But to get to that place (so to speak) would seem to require contestation and dissent, right? When some ways of inhabiting the world are actually dangerous or even deadly to one’s own, it’s hard to think of them as noncompeting. (I don’t think we disagree on this!) It makes me think of the “one no and many yeses” of the counterglobalization movement. We want to get to the many yeses. But what about the no?

MW: Salcedo’s project is certainly one of my favorite works in the last few years. She had surrendered FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) firearms melted down, and, with the collaboration of women who had suffered sexual abuse in the decades-long conflict, hammered them into sheet metal, then used the sheet metal to design and line the floor of the memorial space, Fragmentos, in Bogotá. There is reuse (recycling, if you wish), healing, anger, and the fact that history will stay with us—we can’t simply overcome it with art. You can still take sides, you can scream, be angry at the conflict, patriarchy, rape culture, and everyone should be. This work is so full of conflict that it becomes a physical emotion. At the same time, one can hardly call the intricate planning, building, or even the communal discharge of emotion and its documentation, irrational or naive: it is all done with great thought and care, and constitutes articulate political argument, an informed and principled No. The care is the decision to take the weapons out of the circulation of violence. This can change the future. “No” can therefore be a productive refusal that cares for the future in a broad sense. Then it’s a Yes.

Mechtild Widrich researches art in public space, participatory practices, and the theory of the public sphere. Widrich is the author of Performative Monuments: The Rematerialisation of Public Art (Manchester University Press, 2014) and Monumental Cares: Sites of History and Contemporary Art (Manchester University Press, 2023). She is a professor in the Art History, Theory and Criticism Department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and guest professor at the University of Chicago in fall 2023.

Rebecca Zorach is Mary Jane Crowe Professor of Art and Art History at Northwestern University, where her teaching focuses on art, ecology, and politics. Her books include Blood, Milk, Ink, Gold: Abundance and Excess in the French Renaissance (University of Chicago Press, 2005), The Passionate Triangle (University of Chicago Press, 2011), and Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago 1965–1975 (Duke University Press, 2019).

- Mechtild Widrich, Performative Monuments. The Rematerialisation of Public Art (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press), 2014. ↩

- Miwon Kwon, “From Site to Community in New Genre Public Art: The Case of ‘Culture in Action,’” in One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 100–13. ↩

- See Chicago Monuments Project, Final Report, August 2022. ↩

- Background information and documentation appears at “Whose Lakefront” accessed May 21, 2023. ↩

- See for example Karen Archey, “For photo op, Ai Weiwei poses as dead refugee toddler from iconic image,” e-flux conversations. ↩

- Rebecca Zorach, Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965–1975 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019). ↩