Pedagogies features critical perspectives on teaching and learning where educators share their personal strategies in the classroom, historians consider histories of art education; and artists produce pedagogically inspired artworks.

The sun hung low in the sky, casting a warm and welcoming glow that belied the somber tenor of the spring afternoon as eighteen students stood in front of the memorial garden at Washington and Lee University’s campus, in May 2022. The garden is located along a walkway between two buildings of the historic colonnade and holds the sole marker on campus dedicated to the enslaved individuals once owned and used in the early 1800s by what was then Washington College. Titled “A Difficult, Yet, Undeniable, History,” the historical marker acknowledges the university’s painful past related to slavery.1 Reproduced on the brown metal plaque is the will of John “Jockey” Robinson, the self-made Irish immigrant who bequeathed eighty-seven human beings to Washington College in 1826.2

Front view of the memorial garden with the historical marker acknowledging enslaved people (photo provided by the author)

Detail of the historical marker in the memorial garden. The marker is titled “A Difficult, Yet Undeniable History,” and features a reproduction of the inventory of enslaved individuals in Robinson’s will (photo provided by Kevin Remington)

Unexpectedly, this historical marker—and the history it touches on—became the focus of my 2022 seminar “Forget Me Not: Visual Culture of Memorials.” During the four-week intensive class, students read and examined primary documents related to the ownership and trade of human beings at Washington College. They wrote analytical and personal responses, designed and administered surveys related to Washington and Lee University’s memorials, visited and analyzed memorials in Richmond, Virginia, and spoke with museum directors and public historians. After the first week of intensive study, students in the seminar, who were cross-disciplinarily focused and spanned first years to seniors, felt strongly that it was not enough to study memorials. They felt compelled “to do something” especially in relation to the the historical marker in the memorial garden on campus.3

Here they stood, bravely sharing the fifteen-minute ensemble ceremony we created over the term. The piece, or “ephemeral memorial” as we termed it, was comprised of student reflections, inquiries, and writings related to how and what our university memorializes in relation to its history with enslavement. As the professor of the class, it was important to me that this work was seen for what it was: a well-researched, analytical, and creative act contributing to the institution’s growing dialogue about these troubling histories.4 Below, I share the original concept of the course, the impetus for its 2022 iteration, and the unexpected directions we took together. See here for section on physical campus.

This essay is about pedagogy in practice and brings into focus questions about how we teach with primary sources, material culture, and memorial spaces. As this essay will demonstrate, the course was an effective and powerful exercise in thinking about the forms and functions of memorials. The following focuses on the ways these students activated the memorial garden through the fifteen-minute ephemeral memorial, which was a ceremony open to the college and outside community. The students of the seminar, however, did much more than that: they generated a survey related to on-campus memorials,5 analyzed current legal cases related to Confederate memorials in Virginia, visited museums and spoke with professionals dedicated to public history work, produced an informational pamphlet for the memorial garden, and designed a model for a new campus memorial to enslaved peoples.

The Seminar (and its iterations)

I have been teaching versions of this course since 2013. Each iteration has examined similar issues related to visual culture, memory, and public history within a cross-cultural approach to the world of memorials. The course grew out of my research interests in shrines and memorials in South Asia, so the first course addressed how memorials—secular and sacred—were created and used over time and across regions. Central to that early iteration was the exploration of memory and the ways visual and material culture, along with place and oral history, can reflect, sustain, and control memoryscapes. Some of the memorials we studied were created to commemorate a historic or sacred event. Case studies were paired with theoretical readings about the phenomenology of memory and the power of place to elicit or construct memory.6 Through writing assignments and in-class presentations, students probed the tensions memorials ride between absence and presence, a concern embedded with quotidian interests as much as soteriological. These early courses often ended with students creating a personal memorial or shrine to someone or to an event, loss, or moment in their lives that they wanted to remember and honor.

In each version of this seminar, I used Washington and Lee University’s campus as a case study because it is a powerful example of the ways in which history, place, and hagiography converge in complex ways. Indeed, at the center of much of the university’s identity and memorialization practices are its namesakes: George Washington and Robert E. Lee. It was Lee, the Confederate general, who months after his defeat in 1865 became the president of what was then Washington College. In what is now called the University Chapel (formerly Lee Chapel),7 one will find a larger-than-life marble sculpture of Lee created by Richmond-based sculptor Edward Valentine. The memorial sculpture, commonly referred to as “Recumbent Lee,” was commissioned after Lee died in 1870 and was publicly unveiled in 1883 in the chapel’s newly formed apse, explicitly designed to enshrine the sculpture and the Lee family crypt below.8 Every year, the chapel is visited by thousands of visitors from Virginia and beyond.9 In many ways, this chapel, its cenotaph-like sculpture, mausoleum, and even the preserved spaces, such as Lee’s office in the basement of the chapel, work together to serve as more than a memorial, but a kind of reliquary.10 Consequently, students have a tangible example not only of an active memorial space and its associated iconographies, but the complex ways a secular memorial can become layered with sacred meaning.11

Students visiting Edward Valentin’s Recumbent Lee, University Chapel, Washington and Lee University (photo provided by the author).

Students visiting the Valentine Studio in Richmond. In the foreground is Valentine’s maquette of Recumbent Lee (photo provided by the author).

My students have shown me that analyzing sites on their campus can make a distant and theoretical topic feel immediate and even urgent. Students recognize that these familiar places—seemingly benign as they are part of their everyday routines—are, in fact, intertwined with a complicated institutional history that each student inherits by virtue of association. Through this example, theory and practice merge, which allows students not only to understand, but to experience how memorials function as sites of remembrance shaping both individual and communal memory, and how memory can inform personal and social identities.

2022 Seminar

The national discourse in 2017 and again in 2020 revealed that memorials are potent sites that celebrate and honor, but can also be used to intimidate and invalidate groups of people. In the post-2020 era, teaching a seminar on memorials became a very different enterprise, one that demanded a candid conversation about Confederate memorial-making practices. Consequently, in 2022 the course took as its point of departure public Confederate monuments of Virginia. As an art historian of Tibetan and Himalayan art, it was a daunting, if necessary, task to take on this especially fraught epoch of American history. Though outside my temporal and regional focus, I was living and teaching in Lexington, Virginia, a place steeped in Confederate saint-making and relic-use—things I knew well from my scholarly focus on Buddhist art in the western Himalaya.

Here, however, these practices were used to uphold and glorify a narrative of the Confederacy’s just war. Known as the “Lost Cause,” this account of a noble war circulated as early as 1866 and explains the Confederacy’s defeat while upholding white supremacy and validating racial violence in the guise of noble heritage and family honor.12 The seminar took on the weighty responsibility of examining these monuments to ask what is being remembered and what forgotten, how and why. Students were asked to think about treception and visual culture in order to assess the changing meanings of these monuments over time. In the age of fake-news hysteria and amid claims of young minds being indoctrinated by liberal college faculty, this agenda felt challenging yet imperative.

My art historical goals for the class were twofold. As with my previous seminars, I wanted students to be able to analyze a memorial’s form. This included consideration of iconography and visual vocabulary, context of location (including relation to other monuments and cardinal directions), scale, access, circulation, and other formal elements used in the construction and placement of these sites. The second, though not secondary, focal point related to function-—both synchronically and diachronically. Students would examine original and continued donative practices, audience, and shifting reception over time. Some of the core questions leading our investigations were: Who created these monuments and for whom? What are the visual vocabularies and tactics of display? Whose memory and what narratives are being remembered or upheld? How is the public/collective being asked to remember? How does the public monument affect sightlines and circulation? What rituals, songs, events, or other performative expressions are carried out, why, and when? I asked students to grapple with these questions in order to gain a fuller understanding of the historical moments, associated epistemes, and systems of belief that helped to produce and sustain Confederate memorials in Virginia.

To help students better understand the immediate implications and stakes of these issues, I framed our analysis within the context of contemporary legal battles about Confederate monuments. I wanted students to come away with a strong understanding of the legal disputes regarding removal of public Confederate monuments in Virginia. Two lawyers, Kerri Gould (Washington and Lee law school) and Julie Youngman (previous director of the college’s Law Justice and Society program), attended parts of the course, gave presentations, and addressed legal questions regarding modifications and removal of public Confederate monuments.13 As someone who also teaches about cultural heritage, I found the issue of removal of monuments especially important to investigate. Depending on context and content, removal of material culture can be seen as fanaticism or activism. We placed recent court cases related to removal of Virginia monuments within a larger cultural context and history of memorials in the US, in order to understand how this current moment figures into a long history of adoration and anxiety related to memorials. We also addressed legal discussions about the ways in which the iconography and symbolism of Confederate monuments can contribute to the creation of hostile environments.14

Our class visited several museums in Richmond: the American Civil War Museum, the Valentine Studio, and the Black History Museum.15 At each of these institutions, students had the opportunity to speak with museum directors and curators about how museums can function as memorials and the difficulties these institutions face in curating painful pasts.16 These public historians were exceptionally generous and helpful to us as a class. We saw Valentine’s original maquette for the Lee sculpture and spoke with the director and head curator about the museum’s recent efforts to portray Valentine in all his complexity.

Curators of the Black History Museum met with students to discuss issues of curation and audience. The CEO and curators of the American Civil War Museum discussed the museum’s development and questions of how they display and contextualize material directly related to the Civil War. These lessons stayed with students as they pored over primary source material from the early 1800s from the university’s Special Collections and Archives Department: newspaper advertisements, wills, letters, receipts, and contracts, discussed below.

The Covenant

After the second three-hour class of the first week,17 we were only at the beginning of our inquiry, but already students were processing a great deal of historical information that prompted a range of responses including anger, shame, disgust, and confusion. It became clear to me and the students that the nature and sensitivity of the material we were studying necessitated something more than the usual note in the syllabus about classroom etiquette. We crafted a contract/covenant, something I have never done before or since.18 It was a carefully worded document based on a lengthy conversation we held about our intentions and the course’s scope. Each student contributed, read, edited, and signed the document.

The purpose of the document was to establish a set of shared expectations and to set a tone for the class.19 It was also a way to acknowledge positionality—who we were, each of us—coming into this discussion. While we were not sure what would transpire, we expected that the four weeks would require a great deal from all of us. We needed to show up as engaged, informed, and humble as possible, within a safe environment. We also needed to acknowledge our different positions and privileges, which may cause blind spots. This was predominantly, but not entirely, a class of white students with a white professor. My hope was that we could find ways of talking and listening to one another honestly and compassionately about race, identity, and the legacy of slavery.

On Tuesday, April 26, 2022, the whole class worked together to articulate what we felt were important ground rules for healthy and empathetic communication about complex and sensitive racial and sociopolitical issues of this course, and the strong feelings and responses these issues elicited in each of us. We wanted to be sure to have a set of parameters and expectations that would help guide us through potentially challenging discussions and experiences. Every student contributed to the conversation and contributed to the class covenant. On Wednesday, April 27, we read the document together in class and agreed that, with minor changes, it reflected the intent and spirit of the class. It reads:

One of the most important guiding principles is that we do not judge each other. We understand we are all at different points in our awareness of self and social issues. We are learning to express and articulate our thoughts and to understand better our places of privilege. The hope is that everyone comes to the discussion with respect and integrity. While mistakes may be made, we will walk together on this path asking for guidance when necessary. As such, we will all be invested in creating a safe space of trust and empathy; and these things are generated from respect.

Active listening is something we will all try to employ. This means to acknowledge what others have said, to speak to others using our preferred names, and to validate points others have said when it feels correct/appropriate to do so, e.g. things that have made you think, that make you question, feel, reconsider, etc. Agreement is not necessarily the end point, honesty and civility are.

The “Vegas Rule” applies with a modification: we can take the knowledge we have gained from our class and share that with others, but we will not share specific stories, testimonies, or other similar information outside of this class. We take this measure to protect the safe space we create. It is also a way for us to prevent misrepresenting others’ perspectives and stories.

A final guiding principle is that none of us intend to cause harm to another in the class.

I was amazed by how deeply these students held to the covenant, which allowed them to speak to one another from raw places, often exploring uncharted terrains together. It was never about being perfectly articulate or exactly right, rather it was about being honest and safe in what they had created. Indeed, this was no longer a classroom, this was a community.

Primary Sources

With the ground rules for the course well established on the third day of class, we began work in Washington and Lee University’s Special Collections and Archives department housed at Leyburn Library. In preparation, we discussed what it meant to handle and study primary source material that dehumanized groups of people and promoted trafficking of human beings. It was essential that students could see, touch, hold, and scrutinize these original letters, newspaper articles, contracts, ledgers, advertisements, and broadsides from the 1800s. Students’ engagement with indisputable evidence and historical reality became a revelatory experience for them. Many students expressed feeling deceived by the fact that these truths and realities were housed in an archive that they felt was invisible on campus. While the marker in the memorial garden included a replica of a most wrenching document from the archives, students felt it was hiding in plain sight and did not provide enough context to process. Consequently, the seminar spent more time in the archive and at the memorial garden than I had originally planned. This began the process of shifting the course’s trajectory based on student inquiry and need.

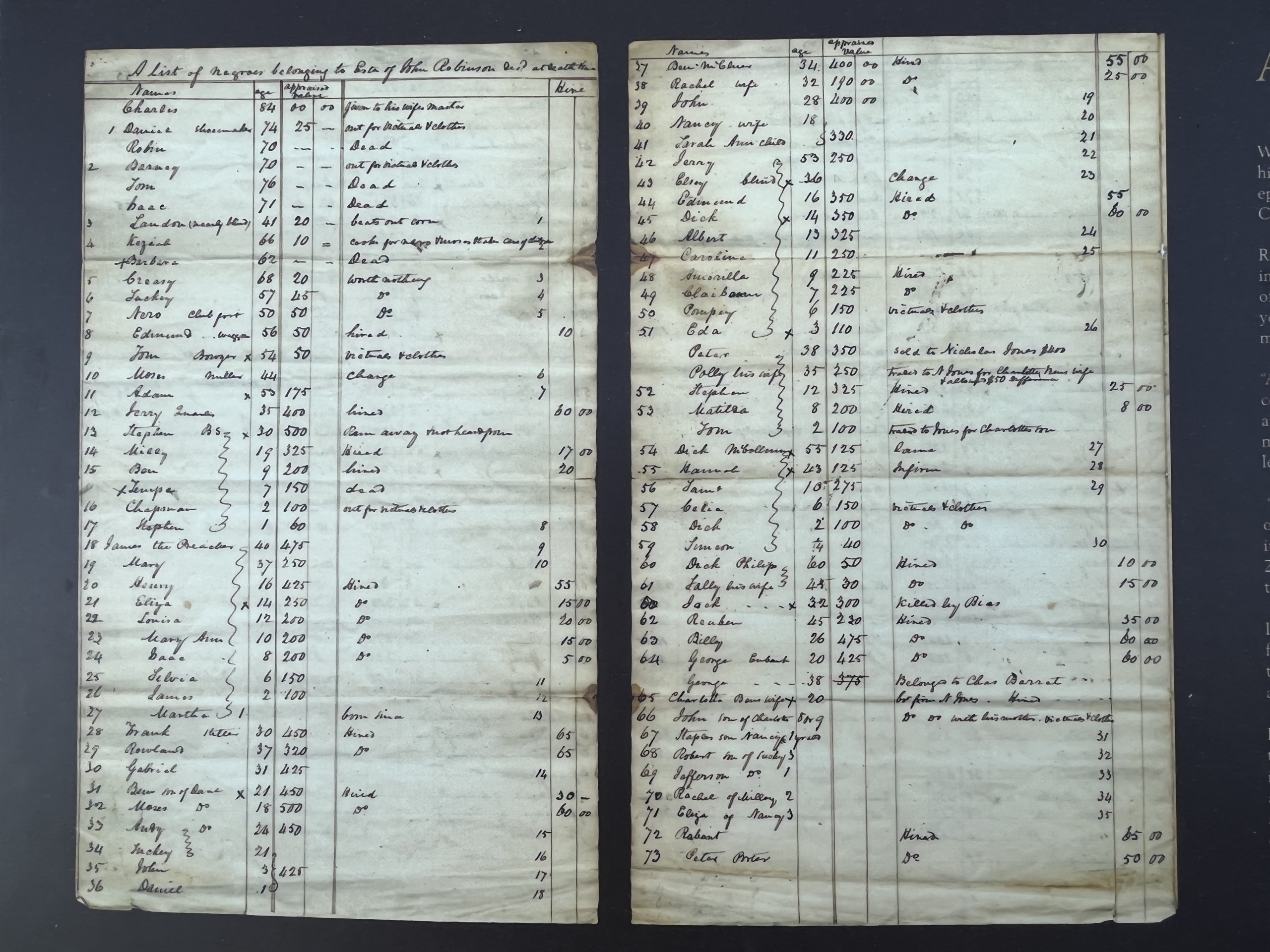

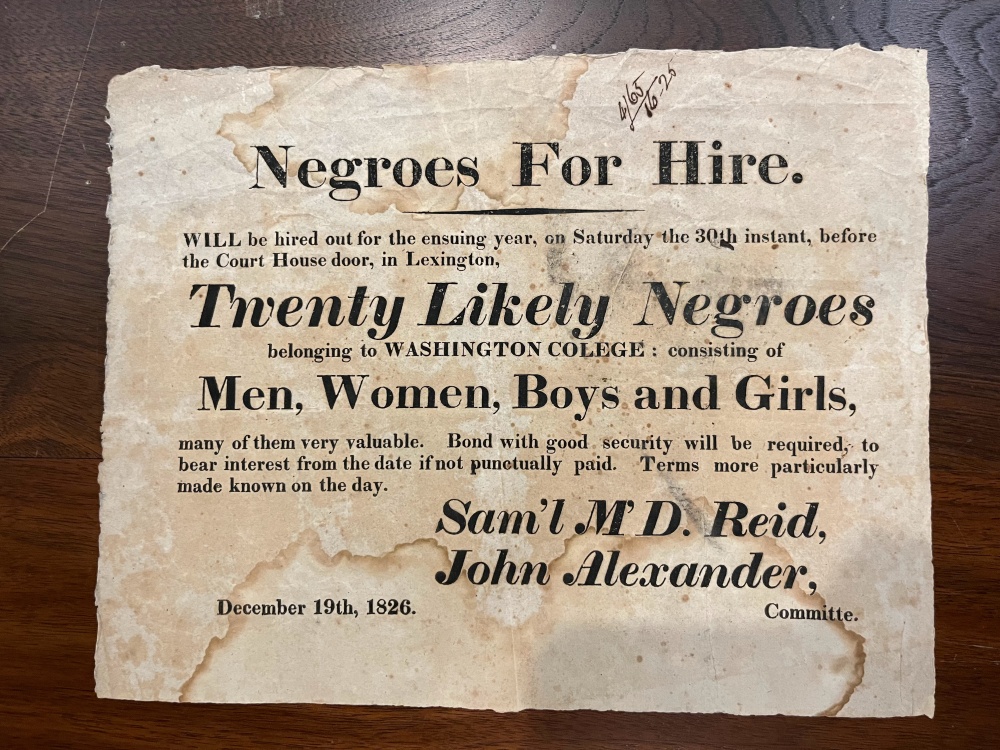

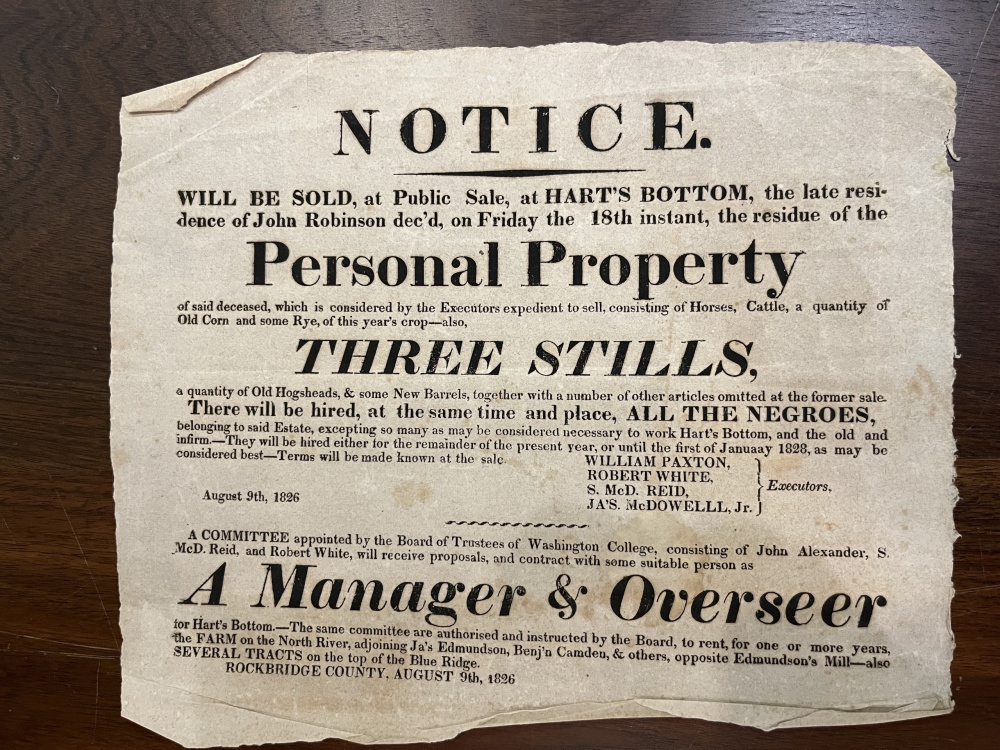

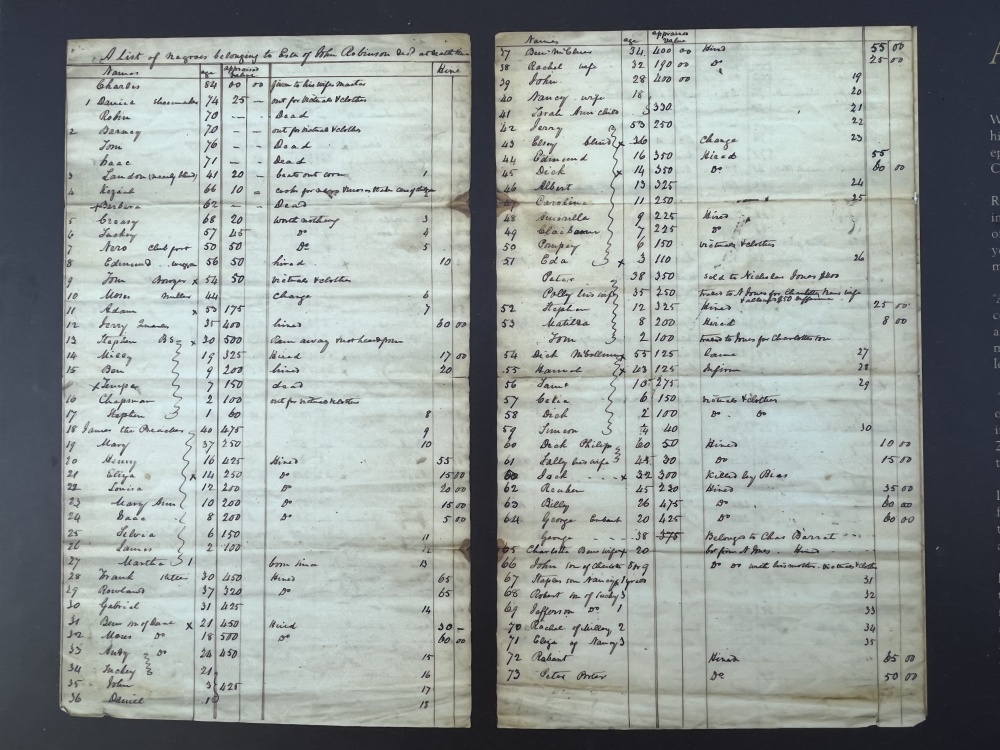

Below are a few of the documents that prompted poignant responses from students, which served as the basis for the ephemeral memorial project. Some of these documents relate directly to Washington College, while others pertain to the town of Lexington or surrounding Rockbridge County. Some of the most unnerving documents were broadsides in local papers from the early 1800s advertising the lease and rent of slaves.

Advertisement in local paper for the hire of enslaved individuals, 1826 (photo provided by the author)

Advertisement in local paper for the hire of enslaved individuals, 1826 (photo provided by the author)

The documents above directly link former trustees of Washington College to these practices. In both cases the enslaved individuals were part of John Robinson’s estate in what is now Buena Vista (then known as Hart’s Bottom). It was he who “gifted” Washington College over eighty enslaved individuals, who the college rented out as laborers after 1826, as these broadsides indicate. Robinson’s will outlines his wishes, and an inventory carefully notes the names, ages, condition, and cost of each person, including children under a year old.20

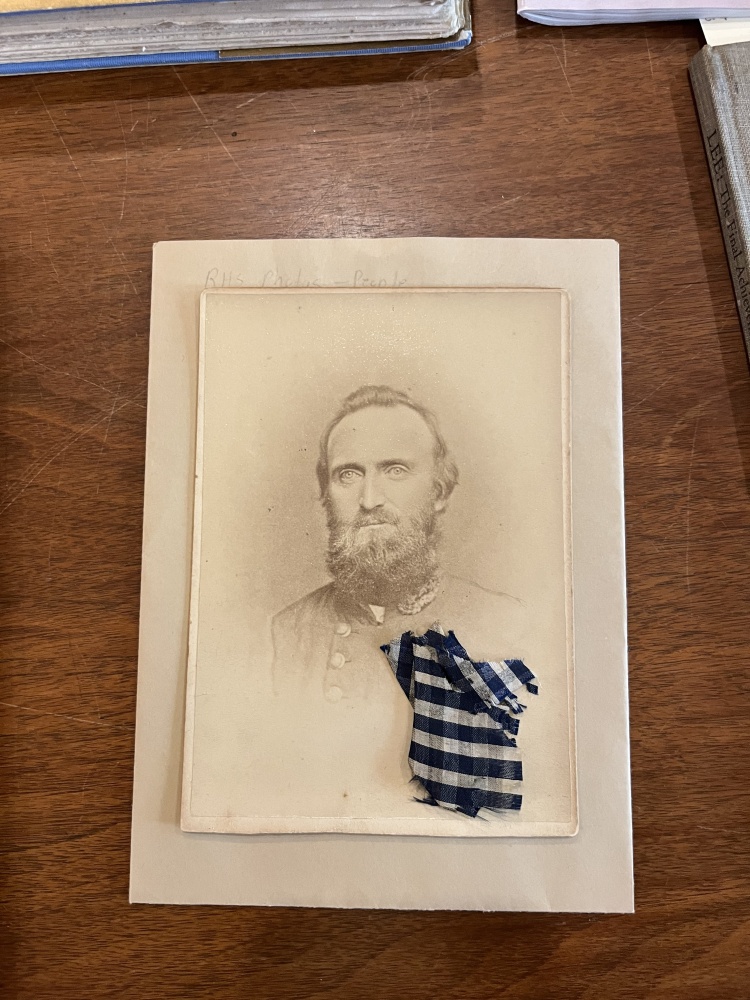

Other objects in the archive evince practices of making saints of Confederate generals, such as Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. The portrait below shows a piece of blue-and-white-checked cotton cloth, supposedly worn by Stonewall in battle. The cloth was sewn to a sepia tone photograph of Stonewall thereby creating a new object, one that enmeshed memory, personal object, likeness and presence, and anticipated the beholder’s tactile engagement. The result was a touch relic for those who wanted to hold Stonewall Jackson close in his absence. While Stonewall does not have a direct relationship to the university, he did live in Lexington, even for a short time on the Washington College campus (not in service of the college, but because he was married to the daughter of Washington College president George Junkin). Despite not having an official connection to the university, Jackson’s name was used alongside Lee’s on one of the most important buildings of campus: Lee-Jackson House, the administrative center of Washington College. Eventually, it became the office of the college deans of Washington and Lee University, and in 2019 was renamed the Simpson House.21

Immediately following the years of the Civil War, newspapers such as the Gazette Banner (1866–69) ran pithy announcements to inform, but also sometimes to incite. For instance, one note reads:

“Noble—We understand that a respected man of color in our town is raising a fund to be used for the benefit of the families [Confederate]soldiers who have gone to the war. Yankees, put that in your pipes—slaves are contributing.” While a great deal can be said about these two sentences, I include it to demonstrate the range of material we encountered in the seminar, which the students sought to contextualize and process.

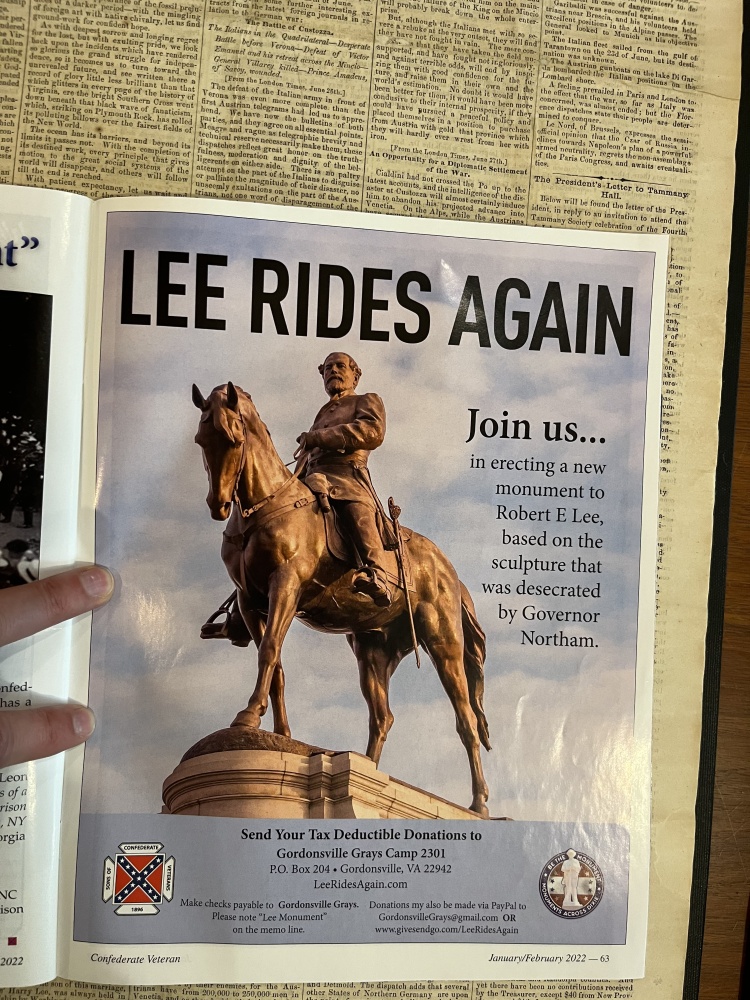

The archive also included materials from the recent past, such as a copy of the Confederate Veteran magazine (2022), which ran an advertisement by the Sons of Confederate Veterans to raise money for a replacement statue of Robert E. Lee in Richmond. The words “Lee Rides Again” are writ large at the top of the page with an image of the Richmond bronze equestrian statue of Lee. These efforts continue to prop up tired but enduring ideas of the Confederacy’s Lost Cause. “Heritage not Hate” is a common refrain of the Sons of Confederate Veterans and others who share a similar sensibility.

These documents raised questions for me about how to teach with objects that have such histories of violence and degradation. Knowing we could not turn away from what we were learning, the question persisted about how best to move forward.22. Were there modalities the class could employ to gain insight from this painful past? I was reminded of Susan Sontag’s provocative quotation, which resonated differently in this situation. In Regarding the Pain of Others, she writes:

Perhaps too much value is assigned to memory, not enough to thinking. Remembering is an ethical act, has ethical value in and of itself. Memory is, achingly, the only relation we can have with the dead . . . Heartlessness and amnesia seem to go together. . . . There is simply too much injustice in the world. And too much remembering (of ancient grievances: Serbs, Irish) embitters. To make peace is to forget. To reconcile, it is necessary that memory be faulty and limited.

Forgetting was not an option now.

Ephemeral Memorial

I explored with students the notion of ethical remembering. 23 What would it mean if remembering became an ethical act? An ethics of remembering asks what is or is not being remembered and why. Who has been omitted from our memoryscapes and why? I presented the possibility that if memorial sites and practices uphold ideologies diminishing the humanity of others, extoll the value of one group over another, engender intolerance and hate, and/or incite violence against a people, such memorials actively work against care and maintenance of civil communal connections.24 By this logic, such sites potentially degrade moral behavior and social responsibility. Given this standard, such memorials would fall outside an ethical practice of remembering. The pedagogical question for me became how the class might use the archival materials to create a more ethical memoryscape.

As a practice of ethical remembering, the class began to analyze Robinson’s will, to ask questions about the individuals in it, the relationships among these people and to begin connecting with the humanity of these people who were otherwise reduced to being part of a commodified list. A good number were children younger than ten years old; one child was an infant only three months old.25 From these exercises came the body of writing for the ephemeral memorial that students performed in front of the memorial garden in May 2022.26 The ceremony script, titled “Forget Me Not: A Memorial Organized and Written for the Enslaved Women, Men, and Children of Washington College,” is based on discrete student writings, brought together to tell a story focused on the power of acknowledgement and accountability, and how these things can potentially lead to healing. The information included in the ceremony below, such as names, ages, and relationships—is factual and derived from primary sources studied by the students, central among these being the nineteenth-century last will and testament of John Robinson.

Students from the seminar gathered around the memorial garden to read sections of the script. There was a lightly choreographed flow of students moving back and forth and through the space.

History Marker Ceremony, May 19, 2022.

Student Valentina Giraldo Lozano (photo provided by Kevin Remington)

As students read the names of the people included in Robinson’s inventory, a Shasta daisy for each individual was set on the brick wall of the memorial garden. It left a powerful trace of the ephemeral memorial on the dark brick wall. The last image of the space after the ceremony was the line of white daisies against the garden that students had helped to beautify by working with university facilities to replace the broken glass lantern, to weed, replant flowers, and mulch. Indeed, the students animated the space in many ways.

Flower offerings made during the memorial (photo provided by the author)

The memorial garden after the ephemeral memorial (photo provided by the author)

These students created a richly layered memorial based on their research, fieldwork, and analysis, and in so doing made visible and audible a painful history anemically taught and memorialized on Washington and Lee’s campus. What these students revealed is that the act of remembering is not simply concerned with the past; it conditions our futures. Through this ceremony, students created a moment and place of ethical remembering that was witnessed by many and created a sense of community beyond the class.27 It happened that the final week of spring term coincided with the week that the university’s trustees would be on campus. Students invited university president Will Dudley to the ephemeral memorial. He graciously attended along with the Board of Trustees’ Rector, Michael R. McAlevey. Several other trustees joined as did the dean of the college, the associate dean, and the provost. Students, professors, staff members, and people from the Lexington community were all in attendance to witness the students’ memorial. This participation at all levels demonstrates the community’s investment in acknowledging and healing this painful past.

Leading this four-week intensive seminar, I learned as much as I had hoped the students, to whom I am so grateful, would. Among the insights, it confirmed for me the most important one was this: painful pasts can be taught, can be learned from, can be a way to deepen the humanity of our futures.

Epilogue

It has been two years since the seminar concluded, and the lessons from our course have stayed with each of us in poignant ways. Haleigh Tomlin ’22 recently wrote me to say: “I’ve thought of this class very often over the past few years. I cannot stress enough the impact it had on me. I still tear up when I share the story of reading the court record descriptions of freed black men, women, and children in Lexington. I’ll never forget sitting on the bench with you after class and describing that experience. I’ll also never forget how clear it was that you were feeling those emotions with us the entire semester and processing it with us.”

Haleigh’s insight captured well the intensity of engaging the archives. While I was aware of the university’s complex history through my work on the Commission on Institutional History and Community,28 there was something altogether different about experiencing this raw and cruel history with students. History became immediate for them—within their hands and under their feet. As another student of the seminar, Jackson Flower ’25, explained that the course asked each student to address “how to grapple with a past that contradicts modern values.” He continued, “As I enter my final year at W&L, I can’t help but feel moved by the legacy of our work, and that our work has stirred an important discussion on campus.”

Though ephemeral, our memorial did indeed inspire and stir conversations and is part of living memory on campus; faculty and students continue to discuss the ceremony in classrooms and refer to it as a model for other ceremonial and rededication practices. I mentioned this when I recently gave a talk to a seminar on memorials at the College of New Jersey. Faculty at the lecture were keen to know if Washington and Lee University had promised resources to create a permanent memorial to the very individuals we honored, or if any effort were afoot to move this memorializing beyond the ephemeral.29 I could only offer that, at present, no plans have been publicly announced for the creation of a permanent memorial (as opposed to historical marker) to the nineteenth-century enslaved individuals at Washington College.

Acknowledgments

I thank all the students in the course for their outstanding work and contributions, and for their permission to use photos and video in this article. I’m also grateful to several colleagues: Dr. Liz Matthews, who helped students create the survey, apply the Likert scale, and process results; Dr. Janet Boller and Professor Judy Dworin, who kindly read and provided much-needed advice on an earlier draft of this paper. I am also grateful for the thoughtful feedback I received after I presented a version of this paper to Dr. Deborah Hutton’s seminar entitled Monuments, Memorials, and Belonging at the College of New Jersey in April 2024 and at the College Art Association in February 2024.

Melissa R. Kerin is the incoming director of the Mudd Center of Ethics at Washington and Lee University. Kerin is also an associate professor of art history focusing on South Asian art and material culture from the medieval and modern periods. She has authored Artful Beneficence (2009) and Art and Devotion at a Buddhist Temple in the Indian Himalaya (2015) and is currently finishing a manuscript, Bodies of Offerings: The Materiality and Vitality of Tibetan Shrines, which received an American Council of Learned Societies Fellowship and a Howard Foundation Fellowship. Kerin’s second research project, Turbans and Turquoise: Patron Portraits in Ladakh’s Basgo Village, wassupported by a National Endowment of the Humanities Summer Stipend (2023). Since joining the faculty of Washington and Lee’s Art and Art History Department in 2011, Kerin has taught a range of courses related to the interconnections among art, architecture, memory, and cultural heritage. Kerin holds a PhD in Art History from the University of Pennsylvania and an MTS from Harvard Divinity School.

- In 2013, Washington and Lee University President, Kenneth Ruscio, created a working group to examine the history of African Americans at the institution. This marker, which was named and erected in 2016, was one of the results of the committee’s work. ↩

- Washington and Lee University was known as Washington College from 1813–70, after which it became Washington and Lee University. ↩

- This was the phrase students kept repeating during that first week of classes. ↩

- Though faulted as slow-going by some and too radical by others, the institution has taken steps since 2013 to document and analyze its relationship to race. In 2017–18, incoming president Will Dudley formed the Commission on Institutional History and Community at Washington and Lee University. In May 2018, the commission produced a report that proposed thirty-one recommendations for the Board of Trustees to implement. ↩

- The survey was used for our seminar, and as the Assistant Provost of Accreditation and Institutional Research explained through e-mail communication: “In your case, the results are intended for a class project (which may include a limited presentation to the W&L community) and, as such, your project does not require IRB approval.” ↩

- Edward Casey, Remembering: A Phenomenological Study; Steven Hoelscher and Derek H. Alderman. “Memory and Place: Geographies of a Critical Relationship.” Social & Cultural Geography 5, no. 3 (2004): 347–55. ↩

- The name of the chapel changed in 2021 from Lee Chapel to University Chapel. During Lee’s lifetime the chapel was known as College Chapel. ↩

- See here for more on the history of the chapel. Lee was originally interred in the chapel basement. ↩

- Based on data from Robert Forsberg, manager of Washington and Lee University’s Visitor Services and Operations, the average number of visitors to the chapel from 2014–19 was 37,000. This number drops to 9,700 per year due to closures related to the pandemic and renovations. ↩

- It should be noted that since 2020, changes to the chapel’s interior were implemented. While more could be written about these alterations, this discussion is outside the parameters of the seminar and this paper. For more on Valentine’s sculpture see Christopher R. Lawton, “Constructing the Cause, Bridging the Divide: Lee’s Tomb at Washington’s College” in Southern Cultures, vol. 15 (2009). ↩

- Indeed, this chapel has been called the “Shrine of the South.” See Pamela Simpson, “The Great Lee Chapel Controversy and the ‘little group of willful women’ who Saved the Shrine of the South,” in Monuments to the Lost Cause: Women, Art, and the Landscapes of Southern Memory, eds. Cynthia Mills and Pamela Simpson (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2003). ↩

- Karen Cox, No Common Ground: Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 15–16. ↩

- City of Charlottesville et al vs. Payne. See Amanda Lineberry, “Payne v. City of Charlottesville and the Dillon’s Rule Rationale for Removal” in Virginia Law Review, vol. 104. ↩

- Deborah R. Gerhardt, Law in the Shadows of Confederate Monuments, in the Michigan Journal of Race and Law 27, no. 1 (2021). ↩

- I am deeply indebted to Dr. Rob Havers, President and CEO of the American Civil War Museum, who had a keen interest in the course. He facilitated connections with the Black History Museum and the Valentine Studio. ↩

- Tim Gruenewald, Curating America’s Painful Past: Memory, Museums, and the National Imagination (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2021). ↩

- Washington and Lee University’s Spring term courses are demanding with at least nine hours of face time a week. ↩

- Northwestern professor Dr. Sarah Jacoby shared the idea of a class covenant with me during the Q&A after I delivered the Myers Foundation Lecture at Northwestern University. “Coming and Going: Marble Sculpture in the Creation and Memorialization of Lives in the Western Himalaya and the US,” April 21, 2022. ↩

- In this way, the agreement was different from a “learning contract” used in self-directed learning environs. Moreover, it was not heavily religious in nature, as is common in covenants within religious programs or institutions. The following essay, though related to a very different topic, was useful in thinking about covenants in relation to painful pasts. Stephanie M. Crumpton, “Trigger Warnings, Covenants of Presence, and More: Cultivating Safe Space for Theological Discussion about Sexual Trauma,” in Teaching Theology and Religion 20, no. 2 (2017): 137–47. ↩

- Images of these documents and transcriptions of them can be found on the working group’s website. ↩

- Simpson House Dedication Address, May 3, 2019. ↩

- Brett Crawford, Diego M. Coraiola, and M. Tina Dacin, “Painful Memories as Mnemonic Resources: Grand Canyon Dories and the Protection of Place,” Strategic Organization 20, no. 1 (December 2020) ↩

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador, 2003), 115. ↩

- Avishai Margalit, Ethics of Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002). Margalit postulates that caring is connected to attention, memory, and ethics. See p. 38. ↩

- University of Maryland College of Education, “Difficult History Project: Teaching with Primary Sources.” ↩

- For notions of memoryscapes, see: Toby Butler, “Memoryscape: How Audio Walks Can Deepen out Sense of Place by Integrating Art, Oral History and Cultural Geography” in Geography Compass 1, no. 3 (2007). ↩

- Students spoke about the possibility of this memorial affecting a greater change and perhaps leading to wider on-campus acknowledgement and healing, and perhaps to a permanent memorial. ↩

- See note 4. ↩

- Dr. Piper Kendrix Williams asked this question of me and suggested I write a coda to provide current information. ↩