During the 1950s, after the devastating defeat in World War II, Japan exerted itself to regain political and economic confidence. Arts and culture played a key role in the country’s recovery: the image of a belligerent nation in the recent past needed to be replaced by a new impression of Japan as a peaceful nation of culture; the people were yearning for a return of their cultural life, or simply, entertainments; and, released from the straitjacket that suppressed free expression, artists quickly resumed their creative activities. This essay focuses on one example of the return of arts and culture in activities of the 1950s: the cross-disciplinary, intermedia art collective Jikken Kōbō (Experimental Workshop). For many, this group signaled the rebirth of avant-garde art in postwar Japan.

Jikken Kōbō consisted of fourteen members: the painters Kitadai Shōzō (1923–2001), Fukushima Hideko (1927–1997), and Yamaguchi Katsuhiro (b. 1928); the printmaker Komai Tetsurō (1920–1976); the composers Fukushima Kazuo (b. 1930), Satō Keijirō (1927–2009), Suzuki Hiroyoshi (1931–2006), Takemitsu Tōru (1930–1996), and Yuasa Jōji (b. 1927); the poet and critic Akiyama Kuniharu (1929–1996); the photographer Ōtsuji Kiyoji (1923–2001); the lighting designer Imai Naoji (b. 1928); the pianist Sonoda Takahiro (1928–2004); and the engineer Yamazaki Hideo (1920–1979). From 1951 to late 1957 Jikken Kōbō created a series of works in collaboration with people outside the group and from a variety of creative fields. The members and their collaborators shared the avant-garde spirit, and above all, they were keenly aware of the urgent need for the rejuvenation and enrichment of cultural life in Japan. The list of the Kōbō’s collaborators reads like a Who’s Who of postwar Japanese arts and culture: for example, the acclaimed modern dancers Masuda Takashi and Tani Momoko, the avant-garde film director Matsumoto Toshio, and the actress Kishida Kyōko, recognized internationally for her seminal performance in the film Woman in the Dunes (1964). Jikken Kōbō also created audiovisual work using a slide projector synchronized with a magnetic tape recorder, with the help of technicians who later named their company sony.

Left to right: Ōtsuji Kiyoji, Takiguchi Shūzō (critic), Akiyama Kuniharu, Mrs. Sonoda Takahiro, Yamaguchi Katsuhiro, Sonoda Takahiro, Komai Tetsurō, Fukushima Hideko, Fukushima Kazuo, Takemitsu Tōru, Imai Naoji, Yuasa Jōji, Suzuki Hiroyoshi, Satō Keijirō.

Many exemplary works of Jikken Kōbō emerged against the backdrop of increasingly industrializing and modernizing conditions in postwar Japan, and the group is considered one of the first postwar avant-garde groups to have pursued an amalgamation of art and technology. It has been included in a handful of exhibitions of the postwar Japanese art and has also been itself the subject of exhibitions.1 However, compared to the international fame enjoyed by the contemporary Gutai Bijutsu Kyōkai (Gutai Art Association), Jikken Kōbō remains elusive to many scholars outside Japan. One particular setback causing the delay of scholarship on this group is its strong affinity to progressive artistic movements of prewar European art, such as the Bauhaus. The similarities to the Western artistic trends, styles, and theories tend to overshadow the Kōbō’s uniqueness in the context of postwar Japan. Its interest and involvement in various traditional disciplines of Japanese arts have been largely neglected, despite the fact that an incentive for such an engagement was present for the Kōbō members insofar as they were the product of the specific cultural milieu of 1950s Japan. This article, therefore, concentrates on the discussion of one of the Kōbō’s works, the 1955 contemporary operatic play entitled Pierrot Lunaire (tsuki ni tsukareta piero), which attempted to transgress the boundary between the experimentalism of Western modern arts and traditional Japanese arts that were resistant to foreign influences. The play combined the music of Arnold Schoenberg and the aesthetic of Noh theater. True to the group’s consistent exercise in collaboration, it was created through a collaboration between Jikken Kōbō and the playwright and critic Takechi Tetsuji. This essay aims to reassess this uniquely eclectic band of artists, thus far mainly considered as an ultramodern group with little validity as an independently avant-garde movement with relevance to the cultural reality of 1950s Japan.2, in 1953-nen raito appu—atarashii sengo bijutsuzō ga mietekita/1953: Shedding Light on Art in Japan, exh. cat., 1997 rep. trans. Reiko Tomii (1953; Tokyo: Tama Art University, 1997), 5–11.]

Experimentation and Tradition

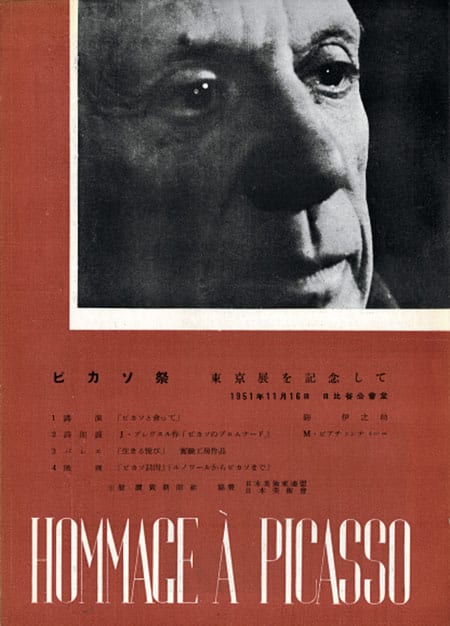

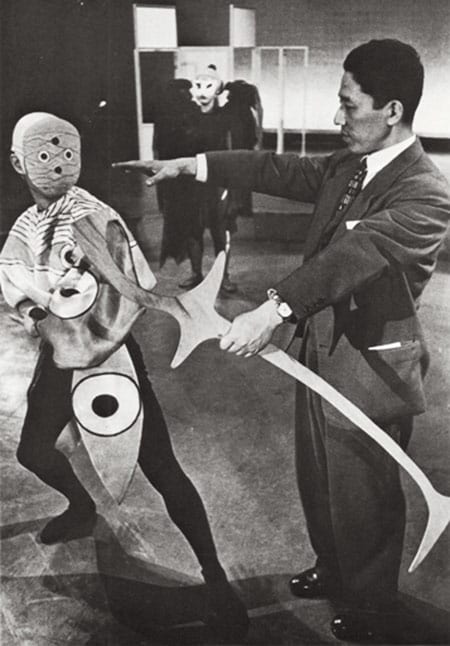

Many of Jikken Kōbō’s works sprung from the members’ interest in Western modernism, ranging from Cubism, Constructivism, and Surrealism, to the Bauhausian pursuit of total art. In fact, the group’s inaugural project in 1951 was The Joy of Life (ikiru yorokobi), a ballet theater work that paid homage to Pablo Picasso’s painting of the same title from 1946. As this modern master celebrated birth, life, and peace in his painting, it was appropriate for the Japanese group to mark the beginning of its collective activity and also to celebrate the rebirth of culture in the postwar environment. In effect, The Joy of Life was Jikken Kōbō’s performative manifesto and reflected some of the ideas that the members expressed in a draft statement written in early 1951 for what they envisioned as their first exhibition:

The purpose of having this exhibition is to combine the various art forms, reaching an organic combination that could not be realized within the combinations of a gallery exhibition, and to create a new style of art with social relevance closely related to everyday life.3

The idea of creating new art together was percolating in the minds of the young artists, and just as they were preparing this statement, a perfect opportunity came to them in the form of a commission from a major newspaper, the Yomiuri Shinbun. This newspaper company was organizing the first Picasso retrospective exhibition in postwar Japan, to open in November 1951, and was creating related programs.

Jikken Kōbō’s production of the ballet theater work The Joy of Life was the highlight of these programs and the group’s contribution to this major undertaking in the cultural landscape of postwar Japan.4 Following the ambitious vision of their draft statement, the Kōbō members created everything from the stage sets and costumes to the lighting and accompanying music, while also collaborating with prominent modern dancers of the time, Masuda and Tani. The performance took place on November 16 at the Hibiya Public Hall in central Tokyo, adjacent to the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers at the time.5 The performance was received by a sold-out audience hungry for such a cultural event after years of depravation. On one hand, from the Kōbō’s perspective, the project fulfilled its interest in art that went beyond the confines of “a gallery exhibition.”6 On the other hand, from the perspective of the Yomiuri Shimbun and the cultural history of postwar Japan, the reintroduction of Western modern art indicated an underlying goal of cleansing wartime xenophobia.

The success of their inaugural project undoubtedly encouraged the young artists to continue their pursuit of new art with liberalism and the spirit of experimentation. However, Jikken Kōbō also found inspiration in Japanese traditional culture, not merely as an alternative to the predominant Western influences, but as an area that would most benefit from radical experimentations. In the background of the group’s interest in traditional culture were various Japanese governmental policies that tried to increase the official measures for conserving artistic traditions, including the performing arts. When considering the issue related to Japanese tradition, the legacy of the Occupation in the sociocultural context of the 1950s cannot be ignored. It is also crucial to take into consideration that this legacy did not always reflect what the Occupation authority actually exercised in Japan during its operative years from 1945 to 1952. This legacy needs to be seen as how the postwar mission of democratization and rebuilding of the country as a nation of culture was understood and undertaken by the Japanese themselves.

On one hand, censorship during the Occupation focused mainly on media such as radio broadcasting and newspapers, and activities in the field of the arts received relatively lenient treatment. However, the Occupation did vilify Kabuki plays and famously banned performance of repertoire such as The Revenge of the Forty-Seven Samurai (chūshingura) because it was thought to idealize the feudalistic mentality. The Occupation authority also objected to filmmakers for using images of Mt. Fuji, as it could be seen as a symbol of imperialism.7 Hōkenteki or “feudalistic” became the umbrella word of most stigmatizing criticism through the experience of the Occupation, and it was frequently used by the general public, although the exact definition of the word remained unclear to many.

On the other hand, the Tokyo Shinbun Newspaper’s reporter Ishida Takeo recalled that at least until the early 1950s there was a general tendency among the people to think anything that associated with “old Japan” as a bad omen. For example, traditional Japanese novels, traditional Japanese poetry, and even the Japanese language itself came under attack in this atmosphere. Ishida summarized the early postwar decade as the period “infested with negative statements about ‘Japan.’”8 (Tokyo: Fujiwara Shoten, 1998), 88–95. Ishida was a staff reporter in the Society and Culture Department of the Tokyo Shinbun Newspaper (the present-day Chūnichi Shinbun, Tokyo Headquarters) starting in 1954. From 1984 to 1986 he was the head of the Culture Department.] Succinctly, the film critic Chiba Nobuo analyzed this negativity toward the concept and images of Japan as a result of “unliberated nationalism.”9, in Zoku shōwa bunka: 1945–1989 [The Shōwa Culture II: 1945–1989], ed. Minami Hiroshi and Shakai Shinri Kenkyūjo (Tokyo: Keisō Shobō, 1990), 252.] In a sense, the legacy of the postwar Occupation was apparent in that the people were given the right of free speech to criticize signs of nationalistic or overtly patriotic sentiments.10 Paradoxically, the idea of “tradition” in general suffered from neglect and a lack of serious reevaluation.

However, by the mid-1950s the memory of the Occupation seems to have gradually receded into the realm of the past. Japan’s economic recovery began at the start of Korean War in the summer of 1950, and by the mid-1950s people could directly feel the recouped financial power. According to public opinion polls about the quality of life, from 1954 and thereafter people became less desperate about making ends meet for daily survival and more concerned about psychological fulfillment.11 (Tokyo: Agency for Cultural Affairs, 1999), 12.] Emblematically, in February 1956 the critic Nakano Yoshio published his article entitled “It is no longer ‘postwar’” (mohaya ‘sengo’ dewa nai) in the literary journal Bungei Shunjū. In the essay Nakano proclaimed that it was time for Japan to stop reflecting on the past, but instead, to direct attention toward the future.12, Bungei shunjū, February 1956, 58.] The country’s regained sense of autonomy, both political and economic, gave a boost to its cultural confidence. While construction of the nation of culture was at the core of the democratization of Japan after 1945, from the mid-1950s there began to appear more outward expression of interest in Japanese tradition and culture.

For example, in November 1955, after viewing a series of museum exhibitions focusing on Buddhist arts, twelfth-century paintings, and so forth, the art critic Takiguchi Shūzō commented on the recently increased efforts in reevaluating classical Japanese art: “Lately Japan’s classical art is being retraced. On one hand, it can be seen as a desire to finally regain self-consciousness a decade after the defeat of war; on the other hand, it is in response to a need to rethink tradition from a global perspective due to increased international communication.”13, Yomiuri Shinbun (November 30, 1955), rep. Takiguchi, Ten [Point] (Tokyo: Misuzu Shobō, 1963), 265.] Takiguchi, however, warned at the same time that “tradition always carries a dual meaning of conservation and creation, and if it were to predominantly operate in a conservative manner, it would become cumulative, fall into stagnation, and turn to be oppressive.”14

It was from this condition that the issue of experimentation and tradition emerged as the central focus of many of the postwar artists, and Jikken Kōbō was certainly not oblivious to it. For example, during the mid-1950s, Suzuki Hiroyoshi and Yuasa Jōji, among other Kōbō members, were enthusiastic about investigating Eastern philosophies such as Buddhism, and particularly the sermons of Suzuki Daisetz (D. T. Suzuki, 1870–1966), an international missionary of Zen Buddhism after the prewar period. They were avid readers of this celebrated Zen master’s publications, especially Zen and Japanese Culture (zen to nihon bunka).15 (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1940).] His thesis “underscored the anti-systematic nature of Zen and relentlessly expressed his contempt for Western philosophy . . .”16 (Tokyo: Ongakunotomosha, 1978), 314; and Tanikawa Shuntarō, “Tanikawa Shuntarō ga kiku, renzoku intabyū: dai 4-kai Yuasa Jōji” [Tanikawa Shuntarō: Series interviews number 4―Yuasa Jōji], in Eiga ongaku/Music for Film, vol. 4 of Takemitsu Tōru zenshū/Complete Takemitsu Edition, ed. Complete Takemitsu Edition Editing Room and Ōhara Tetsuo (Tokyo: Shōgakukan, 2003), 244.] The anti-monistic thinking of Zen bolstered the members’ pursuit of the creation of a multitudinous culture, even with predominantly Western influences.

Jikken Kōbō was also reintroduced to Zen philosophy in the form of John Cage—who was once a pupil of Schoenberg. After the early 1950s, the group recognized the significant deconstructive force of Cage’s music, which defied the strict temporal rules of classical music, and attempted to hold the first concert of his compositions in Japan. By 1952, Akiyama Kuniharu began direct correspondence with Cage. At this time, an incentive to look at elements in their own cultural tradition was sown in the minds of the Jikken Kōbō members for their future projects. By 1955, another group member, Satō Keijirō, wrote in his article “East in the West: Raison d’être de la musique moderne” (seiyō ni okeru tōyō: tōyō no kanousei), that Cage was the “American composer who [was] investigating a new possibility in contemporary music while taking much inspiration from Eastern music (tāla and nō) and thought.”17, Symphony 1, no. 8 (February 1955): 17.] It is particularly interesting that Cagean music, influenced by Eastern spatio-temporal concepts, reconnected Jikken Kōbō to aspects of traditional Japanese culture.

Together with his fellow group members, Suzuki Hiroyoshi was also well aware of the insular mentality that an essentialist view of tradition could conjure. Thus, writing in 1955 in his crucial article “Rediscovery of the East” (tōyō no saihakken), Suzuki warned that a concept of tradition that neglected to find relevance in contemporary reality would not be able to become a true tradition.18, Symphony 1, no. 8 (February 1955): 5.] His statement recalls the two focal points in many Japanese artists’ goals, experimentation and tradition. A persistent theme in postwar Japanese art, this polarity is succinctly outlined as two distinct vectors: “the ambition for the new, virtually and exasperatingly synonymous with things Western,” and “the aspiration for the authentic, often symbolized by things Japanese or Asian.”19 The two ideals, of things Western and Japanese authenticity, are often conflicting for artists, and the tension between them was felt poignantly in the context of the mid-1950s. However, rather than denying the friction between the two, Suzuki envisioned their coexistence within a single artist’s or group’s creative efforts.

In the case of Jikken Kōbō, such a tension provided a creative impulse that realized the unprecedented production of the avant-garde play Pierrot Lunaire. It was the fruit of a timely collaboration between the Kōbō members, who, from the very beginning in 1951, eagerly sought “an organic combination” of intermedia and interdisciplinary art, and Takechi Tetsuji (1912–1988), a dramaturge, playwright, critic, and aficionado of the traditional arts.20 This collaborator with a personality as “lively as a kaleidoscope” held a specific aim of recontextualizing the tradition of theatrical arts for the contemporary time.21, in Enkei gekijō keishiki ni yoru sōsakugeki no yūbe/An Evening of Original Plays by the Circular Theatre, program brochure (Osaka: Dangen-kai, 1955), n.p.] Working with Takechi on the project, Jikken Kōbō found an opportunity to tackle the issue of experimentation and tradition, and to learn, explore, and absorb not only the visual and spatial characteristics but also the musical and temporal elements that are unified holistically in the world of Noh, one of the most revered traditional Japanese performing arts.

Takechi Tetsuji: The Collaborator

The potential for rebound conservatism in the traditional arts was quite high as the “Cultural Properties Protection Act” (bunkazai hogohō) came into effect in May 1950. The legislation followed the unfortunate 1949 fire that destroyed highly valued mural paintings at Hōryūji Temple in Nara, and the protective law received much attention and underwent thorough revision in the first half of the 1950s. The enforced “Cultural Properties Protection Act” superseded early-twentieth-century legislation, and in May 1954 the law was finally established with a system of four categories: 1) tangible cultural properties, 2) folk materials, 3) monuments, and 4) intangible cultural properties.22 With this new legislation the term “cultural properties” (bunkazai) became a familiar word in Japanese. Moreover, the law not only covered all previously protected categories such as buildings, sites, and objects, but in the fourth category also took into consideration support for immaterial properties.

“Intangible cultural properties” (mukei bunkazai) are defined under this law as “theater, music, craft, and other techniques that are intangible products of cultural significance and that possess highly historical and artistic values for the country.”23, in Nihon no mukei bunkazai 2: geinō [Intangible cultural properties of Japan 2: Arts] (Tokyo: Daiichi hōki shuppan, 1976), 272.] In short, immaterial agencies such as human knowledge and skills may now be taken under the wing of official protection. After the 1954 enactment, Noh dance and music immediately received assessment. The first so-called Living National Treasures (ningen kokuhō) certified in 1955, in fact, included the Noh actor Kita Rokuheita, the fourteenth-generation headmaster (iemoto) of the Kita School.24

The national acknowledgement of the artistic value of the performing arts confirmed such traditions as deeply rooted in Japanese culture. However, it also brought a setback. As the succession of many intangible properties depended on safeguarding a lineage, more emphasis was placed on preserving the trades according to convention rather than on rejuvenating them by constant incorporation of imaginative innovations. The stifling condition in the field of theater made some critics, most notably Takechi, cry out for innovation. In the defiance of this reality of rebound conservatism, Takechi undertook a number of bold experiments that challenged the notion of tradition as something just to be preserved as if it were an ossified object.

Born in Osaka in 1912 as the first son of an affluent architectural engineer, Takechi developed a passion at an early age for traditional arts and culture, including Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) painting, Kabuki, Noh, and Bunraku puppet theaters. When most cultural activities were halted under the militant regime, Takechi privately funded a salon of intellectuals and literary figures named the String Breaking Society (Dangen-kai). He considered it “an artistic resistance movement during the war years.”25, Kabuki no reimei: Takechi Tetsuji gekihyōshū [The dawn of Kabuki: Collection of critical writings on plays by Takechi Tetsuji] (Osaka: Shoritsu Seisensha, 1955), n.p. Dangen-kai’s regular members included esteemed literary figures such as Tanizaki Jun’ichirō and Yoshii Isamu.] The String Breaking Society organized performances of Noh and Kabuki by inviting actors deprived of the limelight and held regular gatherings until the very end of the war in August 1945. In December 1949 Takechi proclaimed the beginning of his Kabuki renaissance movement, known as “Takechi Kabuki,” in order to break the stifling conventions in that genre. In the mid-1950s he also began to strike directly at the heart of the Noh theater world and its anachronistic values, habits, and mores.

At that time, Noh theater was arguably the most respected and most conservative of Japanese cultural genres. In addition to this status quo, one effect of the Cultural Properties Protection Act was to give substantial power to senior actors, who formed the Association for Noh and Noh Music (nōgaku kyōkai) that virtually took charge of deciding the proper tradition worthy of official protection. Some Noh actors of the time felt that the old values and forms called kata, that is, certain conventional mannerisms in performance, were undermining their individual creativity. For example, Kanze Hisao (1925–1978), who was still young and quite rebellious at the time, criticized this condition in 1952:

True theatrical arts have not been achieved in Japan perhaps because there is a lack of continuation of tradition. In order to achieve that goal, we must learn and absorb plays of Europe and other cultures. We must directly interact with them in order to truly carry on our classics. . . . That would be the real way of bringing the tradition of Noh back to life.26, Nō (June 1952); rep. Kanze Hisao chosakushū: dentō to gendai [Complete writings by Kanze Hisao: Tradition and the present time], vol. 3, ed. Minami Hiroshi and Dentō-geijutsu-no-kai (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1981), 136–38.]

As a courageously vocal supporter of rejuvenation of the Noh theater, Kanze was frustrated that actors merely followed kata like a diagram of performance handed down from generation to generation for each classic Noh play. Obedience to this dogma led to the dismissal of any involvement by contemporary playwrights, and worse, to complete neglect of the importance of rehearsals.27, Bungaku, May 1954, rep. Kanze Hisao chosakushū: dentō to gendai, vol. 3, 7–19.] Like Takechi, Kanze considered tradition as something constantly evolving and believed in the inherent creative power of Noh. He actively collaborated with Takechi starting in the1950s, when it was still considered sacrilegious for Noh actors to veer away from the time-honored kata.28 Naturally, Takechi’s creative activities that tried to reconnect the lively force of Noh with the equally lively energy of avant-garde art raised eyebrows among those in positions of authority.29 (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1987), 336–81.] Takechi’s conflict with the conservatism of the world of Noh was essentially his struggle with the residue of the old, feudal social construct. Realized in the context of this cultural condition, the 1955 production of an experimental play, Pierrot Lunaire,that incorporated some unique characteristics of Noh theater was truly a groundbreaking avant-garde experiment by Takechi and Jikken Kōbō.

Pierrot Lunaire

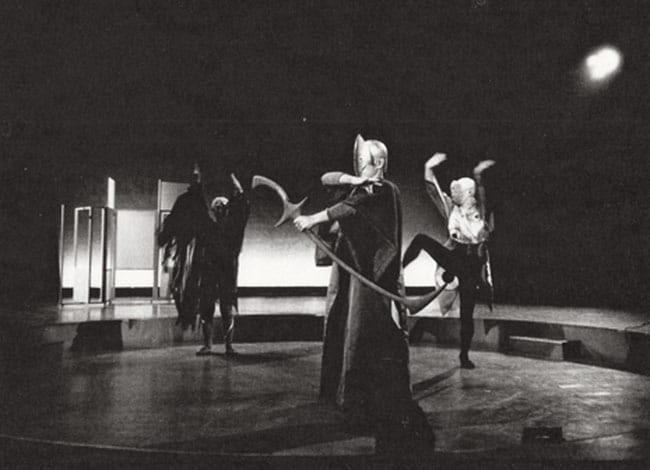

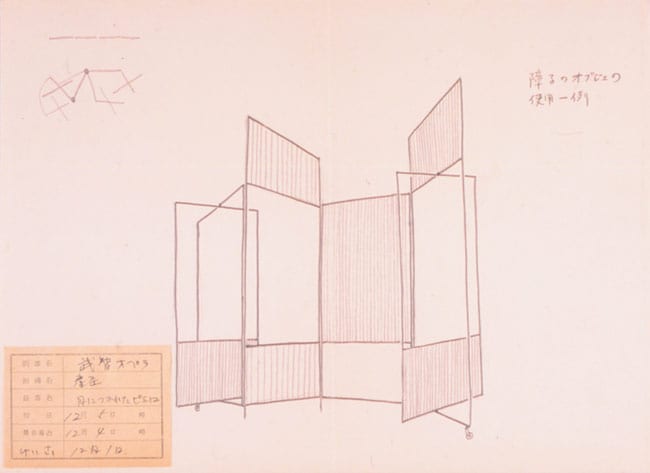

The play Pierrot Lunaire was based on Arnold Schoenberg’s score of the same title composed in 1912. The play was one of two pieces in an event created collaboratively by Jikken Kōbō and Takechi, entitled An Evening of Original Plays by the Circular Theater (Enkei gekijō keishiki ni yoru sōsakugeki no yūbe).30 It took place on December 5, 1955, at the Sankei International Conference Hall in Tokyo. When Jikken Kōbō and Takechi came together to create this play, various preexisting boundaries were challenged, as it incorporated diverse elements.

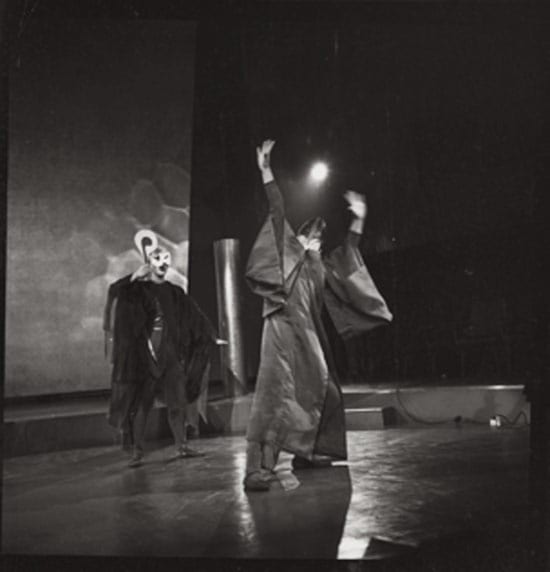

Most notably, Takechi’s vitality and skill as an organizer and stage director brought together three actors from disparate theatrical disciplines on the same stage—an unprecedented event at the time. There were only three characters in Pierrot Lunaire—Columbine, Pierrot, and Harlequin—and they were performed by Hamada Yōko, an actress from shingeki theater that began in the early twentieth century, Nomura Mansaku (1931–2004) from the kyōgen traditional short comedic drama, and the Noh actor Kanze, respectively. Musically, Takechi also bridged Schoenberg’s innovation of Sprachmelodie (spoken melody, more commonly known today as Sprechstimme) with a technique of utai singing used in Noh plays. Although their origins were a world apart, Sprachmelodie and utai both consider the human voice as an amalgam of musical instrument and speech device. Finally, Takechi’s mastery of dramaturgy was fully revealed in his ability to find a common ground in a scientific analysis of human psychology and the nonrealistic approach of the “dreamlike Noh” (yūgen nō). Takechi was not only conversant in the aesthetic of traditional theater but also competent in applying the theory of psychoanalysis and Surrealism in his discussion about the theater of anti-illusionism in which he found the future of the field.

The playbill of Pierrot Lunaire only introduced fragments of the plot, and much was left to the imagination of the viewer. It reads:

Pierrot suppresses his desire and love for Columbine—

Soon, Harlequin appears and tricks Pierrot; being in his element, Harlequin betrays Columbine. Taunted by Harlequin, Pierrot stabs her to death. Yet, Columbine remains alive for eternity within Pierrot himself.31

The story is simple: Pierrot falls in love with Columbine, only to be rejected by her; Harlequin inflames Pierrot’s frustration and tempts him to murder Columbine. However, the more carefully one reads the plot, the more convoluted the context of play becomes: the basis of Pierrot’s longing for Columbine is not clear; Harlequin may be an alter ego of Pierrot; and finally, the whole narrative might be just imagined by Pierrot, a poet intoxicated by wine and the mystifying effect of moonlight. This dreamlike ambiguity of where the subject starts and ends, and who is actually a living being on stage, is analogous to the dramaturgy of a classical Noh play.

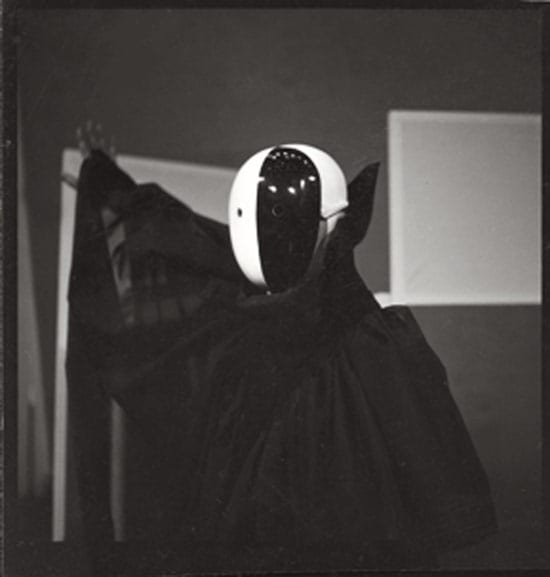

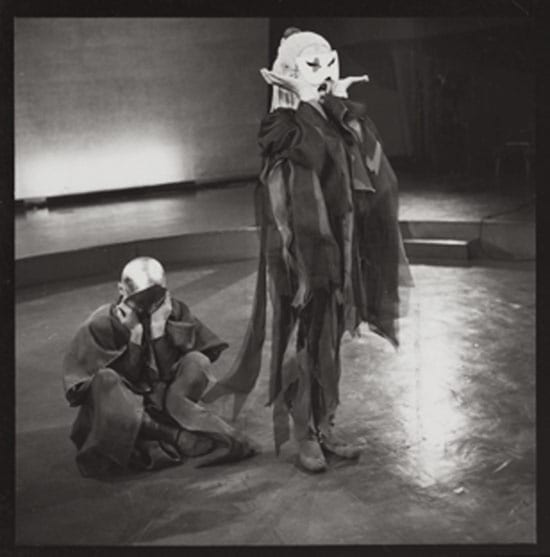

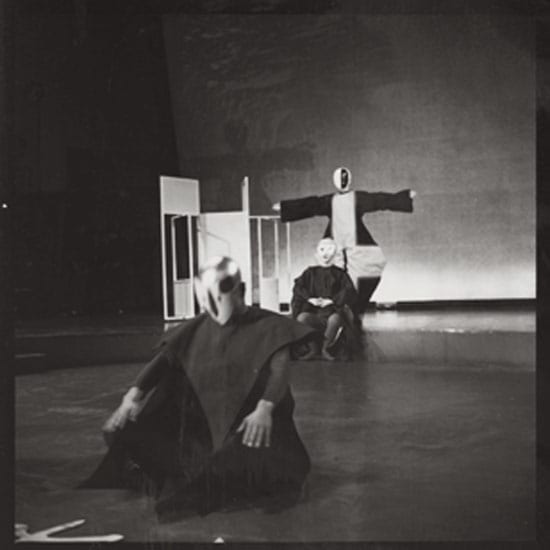

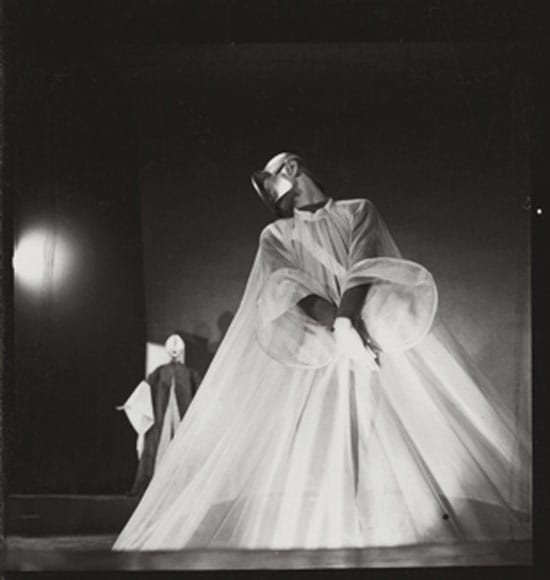

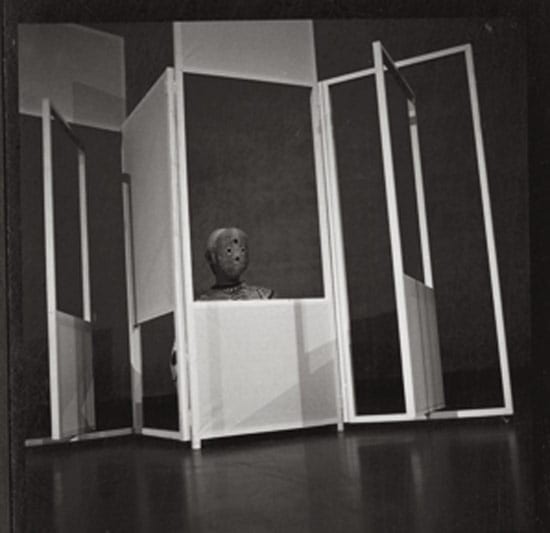

The dreamy atmosphere was visualized on stage by Jikken Kōbō. Within the dim ambient light designed and controlled by the Kōbō’s lighting designer, Imai Naoji, the circular stage appeared to float above the ground, as if to reify the world beyond consciousness. Spotlights in shifting colors guided the viewer’s eyes and illuminated the masked characters.

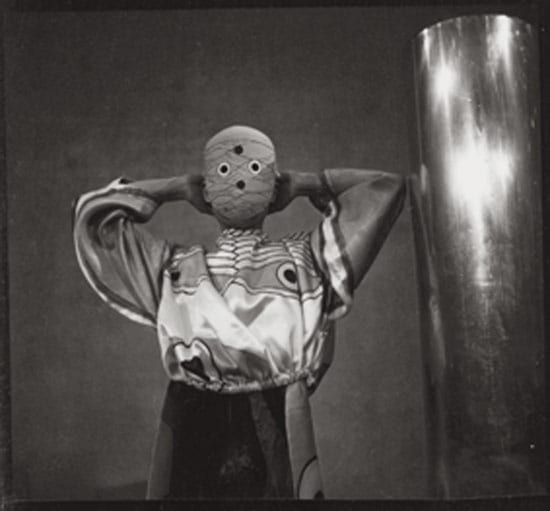

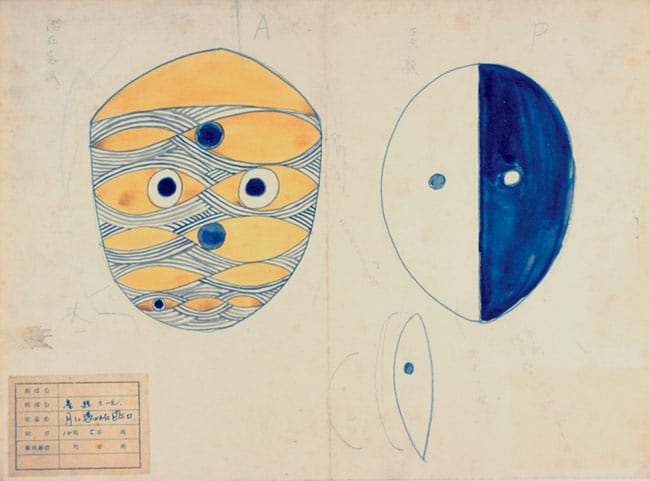

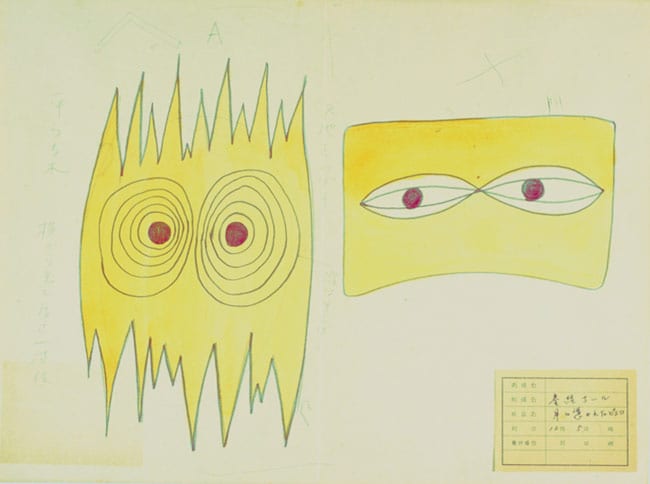

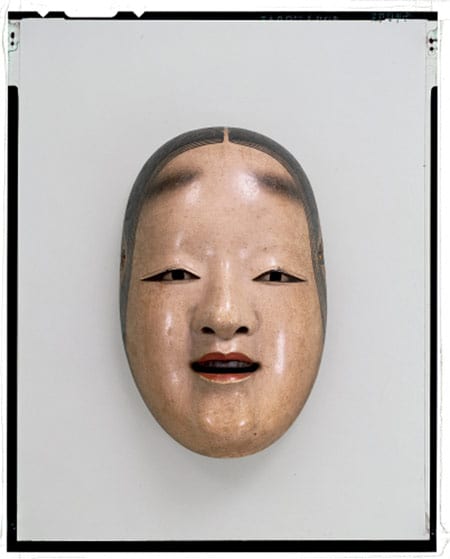

Kitadai Shōzō’s modern mask designs reinterpreted the abstraction of human emotions, a characteristic often mentioned with regard to Noh masks. Highly abstract in form and color, the masks intensified the symbolic nature of the drama. Kitadai believed that faces rarely express people’s true feelings; more often than not, they camouflage the irrationality of human psychology. By dehumanizing his mask designs, Kitadai eliminated realism and its falsehood. The fluidity of expression in the Noh mask of a woman that at first glance is devoid of emotion may have inspired Kitadai’s designs.

In addition, slow choreography created by Takechi in Noh style amplified the physical presence of the actors, while the modern costume designs by Fukushima Hideko orchestrated that effect. The voluminous costumes added a degree of abstraction to the actors’ bodies. A costume for Pierrot, for instance, was made of sheer cloth, and it floated over the actor’s physical contour, fluting out at the bottom hem and attached to a large wire loop. Pierrot’s extremely slow gestures were echoed and amplified by the quivering movement of this dress, expressing the character’s psychological turbulence in a symbolic manner.

In fact, the visual language used to narrate the story throughout the staging of Pierrot Lunaire was more symbolic than mimetic. In the early postwar years, theater was dominated by shingeki, the new theater of realism popularized in the early 1900s during the period of Westernization promoted by the Meiji government (1868–1912). At the time, the traditional Noh play was considered high art that was only performed occasionally, for elite audiences. On the other hand, shingeki was a form of popular theater for the general public. It still exists today as “a theater of dialogue” and realism that relays social issues to the public.32 In stark contrast to the realist approach predominant in the 1950s, Pierrot Lunaire was for the most part a mime that abandoned all conventional plot and a logically developing drama. Instead, Takechi and Jikken Kōbō offered an abstract glimpse into human psychology. Just as a dream unravels hidden human emotions, yet remains incoherent in parts, Pierrot Lunaire was filled with signs that required imaginative interpretation by the audience. For both Takechi and Jikken Kōbō, theater was not an easily consumable form of entertainment. Rather, it provided an emancipating space for the suppressed subconscious.

A stabile made of paper screens by Kitadai Shōzō was one of the few stage sets, and it indicated no specific time and place. The actors’ bodies and the paper-thin stabile painted shadowy patterns on the floor and against the walls, yet those patterns were as hard to grasp as the meaning of the actors’ gestures, as the lighting shifted its color and focus in the flux of time. The sense of being suspended in some amorphous state was heightened by unfamiliar sounds of atonal music. The lyrics, sung by a masked woman, Columbine, added further mystery to the play:

me de nomu sake o / yoru / tsuki ga / nami ni sosogu / shibuki wa / shizukana / suiheisen o / oou / karada wa hageshiku / itaku / hateshinai umi o sagasu / sora o aogi / koe naku / inori nagara / shijin wa/ yoromeki / yoishireru / (yome wa sake o nomu) / tsuki ga sosogu / aojiroki yoru no umi no nioi / tsuki ni you

(The wine which through the eyes we drink / Flows nightly from the moon in torrents, / And as a spring-tide overflows / The far and distant land. / Desires terrible and sweet / Unnumbered drift in floods abounding. / The wine which through the eyes we drink / Flows nightly from the moon in torrents. / The poet, in an ecstasy, / Drinks deeply from the holy chalice, / To heaven lifts up his entranced / Head, and reeling quaffs and drains down / The wine which through the eyes we drink.)

kuroi / ōkina chōno mure / hikari o koroshita / fushigina / hon wa tojirareru / hakaba kara / nioi ga hirogaru / kuroi chō ga / taiyō o koroshita

(Heavy, gloomy giant black moths / Massacred the sun’s bright rays; / Like a close-shut magic book / Broods the distant sky in silence. / From the mists in deep recess / Rise up scents, destroying memory. / Heavy, gloomy giant black moths / Massacred the sun’s bright rays.)33

The lyrics of Schoenberg’s music, originally written in French by the Belgian symbolist poet Albert Giraud (1860–1929), were translated into Japanese for the play by Akiyama Kuniharu. The mezzo-soprano voice of the shingeki actress Hamada achieved the effect of Sprachmelodie, whose purpose was to move away from Western musical convention by assimilating the temporal irregularity, the intonation patterns, and the spontaneity of human utterance. Schoenberg’s experimental use of the human voice, in turn, proved to have an affinity with utai, a vocal accompaniment of Noh performance. Keenly observing the affinity, the Kōbō member Yamaguchi Katsuhiro stated that Sprachmelodie would come vividly alive, when contrasted with Takechi’s Pierrot Lunaire in the abstract visual and gestural style of Noh, just as utai, by subtly drifting above the mechanical nature of instrumental music, functions to keep the audience aware of tension between the earthly world and the otherworldly realm of the spirits commonly portrayed in Noh plays.34, Bijutsu hihyō 49 (January 1956): 11.]

Conclusion

In Pierrot Lunaire, Jikken Kōbō and Takechi contested modern rationalism by abstracting all referential elements to the maximum degree: in the play’s narrative aspect, through the physicality of the space of performance and the dancer’s body, and in its temporal element of movement. In addition, it was critical for the Kōbō and Takechi to engage the imaginative power of the spectator. In a defiant tone, Takechi asked his audiences, “The experiment of masked dance in the-theater-in-the-round—freed from a frame and freed from actors—what sort of play would emerge from it? What influence would it have on the future of playwriting? And how would it save us from the sickness of typical drama?”35, in Enkei gekijō keishiki ni yoru sōsakugeki no yūbe, n.p.]

Specialists and performing arts critics had long been oblivious to such “sickness” and initially denied the creative potential of this play. Yet artists and art critics who were involved in avant-garde art offered high applause. Takechi felt warm encouragement from the positive reception of the avant-garde artistic circle, and he seems to have particularly appreciated the recognition of the art critic Takiguchi Shūzō. In his 1958 publication My Discussions about Drama (Watashi no engeki ronsō), Takechi quoted Takiguchi’s comment from his “Closed and Open Classics” (Tozasareta koten to hirakareta koten) at length:

Finally, I must address an experimental work which in the most concrete way presents the problem of tradition and creativity. The work is Takechi Tetsuji’s production of “Original Plays for a Circular Theater.” . . . Some have criticized this as pastiche, grafting trees with bamboo. In the world of Noh and Kabuki, where ancient traditions are preserved in the flesh, no amount of abstract speculation on tradition versus creativity will get very far. Aren’t experiments like these, grafting trees with bamboo, exactly what is called for? The real significance of these productions is that they are essentially different from attempts at compromising modernizations on the order of “modern Noh” or “New Japanese whatever.”36 (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1958). The quoted section is reprinted in Teihon, Takechi kabuki: nō to zen’ei, 140. Takiguchi Shūzō’s “Tozasareta koten to hirakareta koten” originally appeared in Bijutsu hihyō, January 1956, 77–81. This English translation of the article is from Experimental Workshop, ed. Satani Gallery (Tokyo: Satani Gallery, 1991), 21.]

Takiguchi understood Takechi’s achievement not as a compromise but as the creation of a new type of lyrical play. The element of lyrical play, to Takechi, was inherently present in the true essence of Noh. In other words, Takechi explained that he was not superficially adopting the existing formula of Noh to create a new play but trying to imagine the way that Noh would have developed, if it were not limited within the sectarian system of iemoto or other organized institutions such as the Association for Noh and Noh Music.

However mixed the reception, the authorities could not ignore Takechi’s avant-garde collaborative work with Jikken Kōbō forever. The renowned historian of early modern Japanese popular culture Nishiyama Matsunosuke noted that Pierrot Lunaire was an enlightening avant-garde experiment that startled the audience. He also credited Takechi for his “theory of denial” (hitei no ronri), that is, rejecting the conventional format of stage, dramaturgy, music, and the use of the actors’ bodies, and, above all, denying the tradition of Noh as an impenetrable and fixed remnant of the past.37, in Dentō towa nanika [What is tradition], vol. 1 of Dentō to gendai [Tradition and the present time], ed. Minami Hiroshi and Dentōgeijutsu-no-kai (Tokyo: Gakugei Shorin, 1968), 200–4.] Similarly, Kawatake Toshio, a great-grandchild of the late nineteenth-century Kabuki dramatist Kawatake Mokuami, stated: “It was from after 1955 that the new, modern people in Japan began to recognize surprisingly many super-modern elements in traditional theatrical arts. . . . I think much initiative was taken by Mr. Takechi Tetsuji, and he was influential.”38, ed. Geijutsushi Kenkyū-kai, vol.10 of Nihon no koten geinō [Classical arts of Japan] (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1971), 170.]

Pierrot Lunaire attested to an eclecticism and experimentalism only possible through collaboration among the avant-garde artists, the actors from the different backgrounds, and the energetic creator and producer Takechi. Working closely together, they united the avant-garde essence of Schoenberg’s music, the modern analysis of the human mind, and the nonmimetic, minimalist aesthetic of Noh theater. The collaboration ultimately created a new type of drama or engeki that challenged various boundaries within Japanese theater, and opened up engeki to culturally diverse elements, not for the sake of denying tradition but for the sake of releasing it from its preserved condition so that it could be revitalized as a living cultural identity.

Strong conservatism in the traditional theatrical arts was an unfortunate byproduct of postwar national preservation efforts in arts and culture, but it was also a perfect adversary for those with experimental minds in the following decades of the 1960s and 1970s. In fact, the activities of Jikken Kōbō and Takechi might have given an impetus to the 1960s avant-garde performing arts movement, the shō-gekijō (small theater) movement, that produced such visionary dramatists as Terayama Shūji, Suzuki Tadashi, and Ninagawa Yukio, to name just a few.39 To the eyes of this later generation of dramatists, Pierrot Lunaire is “the classic of the avant-garde play” that marked the beginning of the search for cultural identity in the postwar theater art.40

Miwako Tezuka is an associate curator at Asia Society in New York. A specialist in Asian contemporary art, she cocurated Yoshitomo Nara: Nobody’s Fool (2010) and curated U-Ram Choe: In Focus (2011), among many other exhibitions. She is also a cofounder of PoNJA-GenKon (Post-1945 Japanese Art Discussion Group), a global online network of over one hundred fifty specialists and students working in the field of contemporary Japanese art.

In this article, Japanese names are written in order of the family name followed by the personal name, according to the East Asian convention. All translations, unless otherwise noted, are mine. I would like to thank Dr. Tomii Reiko for her sage advice, and also Dr. Nishizawa Harumi for sharing research materials related to Jikken Kōbō and information regarding the most current studies on Jikken Kōbō, including her own, “1950-nendai o chūshin to suru bijutsu to butai-geijutsu ni kansuru kenkyū” [Art and performing arts in 1950s Japan] (PhD dissertation, University of Tsukuba, 2010). Most recently, Dr. Nishizawa presented on the topic of cross-genre collaborations in Takechi Tetsuji’s experimental theater of the 1950s at the symposium “Takechi Tetsuji—Tradition and Avant-Garde,” June 12, 2010, Meiji Gakuin University, Tokyo.

- Recent exhibitions include Art, Anti-Art, Non-Art: Experimentations in the Public Sphere in Postwar Japan, 1950–1970, Getty Center, California, March 6–June 3, 2007; and Experimental Workshop: Japan 1950–1958, Annely Juda Fine Art, London, October 29–December 18, 2009. Catalogues accompanied both exhibitions. The latter includes essay contributions by Jasia Reichardt, Obinata Kin’ichi, and Ōtani Shōgo. ↩

- See Minemura Toshiaki, “Sōjo” [Introduction ↩

- Satani Gallery, ed., Dai 11-kai omāju Takiguchi Shūzō ten: Jikken Kōbō to Takiguchi Shūzō/The 11th Exhibition Homage to Shuzo Takiguchi: Experimental Workshop, trans. Tom Spilliaert (Tokyo: Satani Gallery, 1991), 102. ↩

- The performance was followed by the screening of two films, Visite à Picasso and De Renoir à Picasso, both from 1950, by the Belgian filmmaker Paul Haesaerts. ↩

- For details about the Allied Occupation, see Takemae Eiji, The Allied Occupation of Japan (New York: Continuum, 2002). ↩

- Another significant example of Jikken Kōbō’s transgressive activity involving dance is its production of the experimental ballet theater work The Future Eve in 1955. Developed in collaboration with the dramatist Kawaji Akira and the Matsuo Akemi Ballet Company, it was performed at the Haiyūza Theater in Tokyo and ran for three days, March 29–31, 1955. The story was based on the French science-fiction novel L’Ève future, written in 1886 by Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam (1838–1889). ↩

- See Donald Richie, “The Occupied Arts,” in The Confusion Era: Art and Culture of Japan during the Allied Occupation, 1945–1952 (Seattle, London: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and University of Washington Press, 1997), 12. ↩

- Ishida Takeo, Haisen kokumin no seishinshi: bungei kisha no me de mita 40-nen [Psychological history of the defeated people: Forty years of observation from a cultural journalist’s perspective ↩

- Chiba Nobuo, “Eiga—rekishi to shinri” [Movie—a history and psychology ↩

- The critical view on the legacy of the Occupation in postwar Japanese arts and culture became a central issue in the late 1970s through the polemics of critics such as Etō Jun. See, for example, Etō’s “The American Occupation and Postwar Japanese Literature: The Impact of Censorship upon a Japanese Mind,” Hikaku bungaku kenkyū 38 (September 1980). ↩

- See Agency for Cultural Affairs, ed., Atarashii bunka rikkoku no sōzō o mezashite—bunkachō 30-nen shi [Toward founding of a new cultural nation—the thirty-year history of the Agency for Cultural Affairs ↩

- Nakano Yoshio, “Mohaya ‘sengo’ dewa nai” [It is no longer ‘postwar’ ↩

- Takiguchi Shūzō, “Koten geijutsu no saihyōka” [Reevaluation of classical art ↩

- Ibid., 265–66. ↩

- Suzuki Daisetz, Zen to nihon bunka [Zen and Japanese Culture ↩

- Bernard Faure, “The Kyoto School and Reverse Orientalism,” in Japan in Traditional and Postmodern Perspectives, ed. Charles Wei-hsun Fu and Steven Heine (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995), 246.This reference to D. T. Suzuki was made during the author’s interview with Yuasa (January 26, 2001) and was frequently repeated by the Kōbō members elsewhere. See, for instance, Akiyama Kuniharu, Nihon no sakkyokukatachi: Sengo kara shinno sengotekina mirai e [Japanese composers: From the postwar period to the true postwar future ↩

- Satō Keijirō, “Seiyō ni okeru tōyō: Tōyō no kanōsei” [East in the West: Raison d’être de la musique moderne ↩

- Suzuki Hiroyoshi, “Tōyō no saihakken” [Rediscovery of the East ↩

- Nakajima Masatoshi and Tomii Reiko, “Readings in Japanese Art after 1945,” in Japanese Art after 1945: Scream against the Sky (New York: Abrams, 1994), 380. ↩

- See Satani Gallery, 102. ↩

- Toita Yasuji, “Kakezan no omoshirosa” [The fun in multiplication ↩

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Chapter 8: The Administration of Scientific and Cultural Affairs, Section 2, The Protection of Culture and the Administration of Cultural Affairs, Subsection 4, The Protection of Cultural Properties, available in Japanese at www.mext.go.jp/hakusyo/book/hpbz198103/hpbz1981032215.html. ↩

- Honda Yasuji and Ishizawa Masao, eds., “Mukei bunkazai hogo no gaiyō” [Summary of measures to protect the intangible cultural properties ↩

- Ibid., 97. ↩

- Takechi Tetsuji, “Jo” [Foreword ↩

- Kanze Hisao, “Korekara no nō” [Noh of the future ↩

- See Kanze Hisao, “Genzai no nō to Zeami no nō” [Today’s Noh and Zeami’s Noh ↩

- The veneration with which the old formulas were maintained, in fact, resembles a religious fervor. Headmasters of Noh schools even held the right to excommunicate any disciples who disrespected the principal traditions of their schools by experimenting with new ideas. When Takechi directed another operatic work, Nō-style Yūzuru (Nō-style Night Heron), in 1954 with Kanze as one of the performers, the Association for Noh and Noh Music opposed the Noh actor’s involvement in the production. ↩

- That these authorities in their devotion to the preservation of tradition held nearly tyrannical powers was a frequent topic of criticism among more liberally minded individuals, such as Kanze and Takechi. The journal Kagaribi (Bonfire), first published in April 1949 by a group of liberal actors including Kanze Hisao and Kanze Shizuo, among others, and the musical drama critic Yokomichi Mario, published critical debates on the system of iemoto and on the generally bigoted purism of the field. For more on contemporary Noh theater, see Yokomichi Mario, Nishino Haruo, and Hata Hisashi, eds., Nō no sakusha to sakuhin [Noh playwrights and their works ↩

- The format of circular theater, or enkei gekijō, which required no proscenium arch (gakubuchi butai), was frequently employed, for instance, by the theater group of Waseda University because the common lack of theater facilities in the early postwar years necessitated a makeshift stage environment. ↩

- Enkei geikijō keishiki ni yoru sōsakugeki no yūbe, n.p. ↩

- See Ōzawa Yoshio, “Shingeki’s Restless Century,” UNESCO Courier 50, no. 11 (November 1997): 19. The introduction in Japan of plays by Henrik Ibsen, such as John Gabriel Borkman (premiered in 1909) and A Doll’s House (1911), marked the beginning of the modern theater movement (shingeki undō). Shingeki not only popularized theater but also opened the field for female actors, who had been banned from the traditional stages of Kabuki and Noh. ↩

- The sections quoted here are from Akiyama Kuniharu’s fragmentary Japanese translation of Giraud’s Pierrot Lunaire in Bijutsu hihyō 49 (January 1956): 6 and 8. For these two stanzas, entitled “Moondrunk” and “Night,” respectively, I referred to Cecil Gray’s translation in the notes with a CD, Arnold Schoenberg, Pierrot Lunaire, op. 21 (Koch International, CD 310 117 H1), n.p. The rest of the stanza “Night” continues as: “And from heaven earthward bound / Downward sink with somber pinions / Unperceived, great hordes of monsters / On the hearts and souls of mankind . . . / Heavy, gloomy giant black moths.” ↩

- See Yamaguchi Katsuhiro, “‘Tsuki ni tsukareta piero’ jōen o megutte” [On the performance of Pierrot Lunaire ↩

- Takechi Tetsuji, “Enkei gekijō no kokoromi” [Experiments in a theater-in-the-round ↩

- Takechi Tetsuji, Watashi no engeki ronsō [My discussions about drama ↩

- Nishiyama Matsunosuke, “Sengo dentōron o furikaette” [Reviewing the postwar theory of tradition ↩

- Kawatake quoted in Hikaku geinō ron: nihon to sekai no geinō [A comparative study on arts: Arts of Japan and the world ↩

- See Senda Akihiko, Performing Arts Now in Japan: Trends in Contemporary Japanese Theatre (Tokyo: Japan Foundation, 1994). ↩

- Takechi, Teihon, Takechi kabuki 207. ↩