For several days in 2000, William Pope.L sat enthroned on a towering toilet, contemplating and quite literally consuming The Wall Street Journal, dusted with white powder and surrounded by the great American fluids—milk and ketchup. This performance grew from an earlier 1991 version, staged on the street, and the artist has reenacted the performance several times since, most recently at the New Museum in New York in 2010. This most recent version was performed by multiple participants in Obama masks, complicating the original issues of race and money with reference to a black American president. At this writing, in late 2011, the performance has taken on a fresh urgency and relevance in the light of a new political wave encompassing Wall Street and far beyond, one that seeks to displace and shatter the illusions of high finance’s importance that grip us so powerfully.

The issue of reenactment drives much of contemporary discourse on performance art, and it is the central subject of Amelia Jones’s round table on performance. Do new contexts reanimate past performances, or are historical reenactments zombie reincarnations, risen from the dead at the behest of the museum? The participants strenuously test the implications of Jones’s questions; most pressing perhaps for scholars is whether to focus on the live event or on the traces, documents, and histories that accumulate around it. For artists, the question may be broader; as Pope.L asks in his contribution, is performance art the canary in the coal mine?

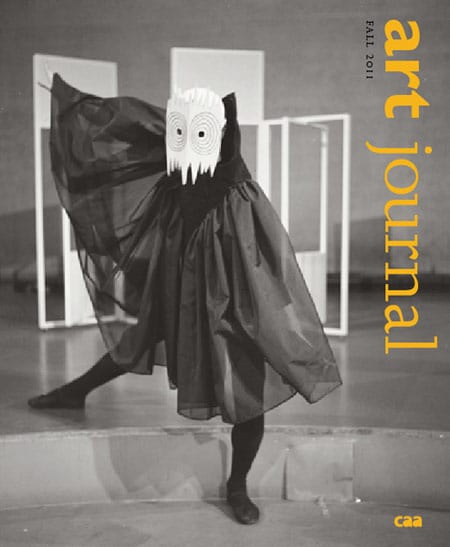

Miwako Tezuka’s essay on the Japanese postwar avant-garde collective Jikken Kōbō is one of the most interesting and original I have had the privilege to publish. The intersection of avant-garde experiments in theater, dance, music, and art created striking imagery and concepts; it is hard to imagine that this work was often overlooked as derivative—repetitive—of earlier European art. As the contemporary critic Takiguchi Shūzō observed, “Aren’t experiments like these, grafting trees with bamboo, exactly what is called for?”

Sarah Kanouse makes a case for radio as another medium suited to live or performance art as a kind of public art. Because the regulated nature of this form of communication—radio-as-art usually means pirate radio—the medium forces artists to consider their work’s political implications. Many of the artists she discusses further turn radio into a two-way, participatory medium, with two or more agents acting on each other, rather than playing the usual roles of broadcaster and listener.

Finally, Krista Thompson writes the Centennial essay for this issue, an overview of African diaspora art history. Masterful in its history and historiography, and critical in its account of the institutional elision of African diaspora and African art histories, Thompson’s essay brings us to the question of Africa itself as a receding source. She argues that the “African” is often impossible to see and definitively locate in the diaspora and its art, and there has been a disciplinary turn toward emphasizing the dominant “Western” art context for diasporic subjects, following the black Atlantic model of the scholar Paul Gilroy. As befits the breadth of her scholarly perspective, Thompson explores the various aspects of this conumdrum.

Pope.L seems to comprehend both possibilities and find the connections between them. In an essay titled “Bocio,” after a West African ritual object, he critiques the possibility of his own relation to African sources and the tendency of scholars to relate him to Africa as a black artist. Conversely, he locates the magical thinking—with the WSJ as ritual token—in modern capitalism. In reenactment—even in reproduction—the power of the of the work lives.