i

The archive, with its icy temperature and motionless repose, may seem like an unlikely place to begin thinking about Occupy Wall Street (OWS), a dynamic and still-unfolding phenomenon whose precise nature appears impossible to determine, let alone file away like a stack of dog-eared documents. Unlikely, if we approach the idea of the archive as a physical collection located in a specific time and place, or as a set of historical documents that uphold this or that interpretive school. But what if we invoke something like an archival agency, something that now and then animates the longue durée of resistance “from below.” After all, things have changed since we witnessed the power-scrubbing of Zuccotti Park’s People’s Library1 and the mulching of the encampment’s hundred-page opus of dissent written on corrugated scraps of cardboard and inverted pizza boxes, some torn, trimmed, or simply folded down into manageable dimensions for extended protest. We witnessed the demolition as an echo of the Baghdad library’s destruction eight years ago, when US and UK troops stood by as that archive was reduced to ashy pulp. 2 It is this we must grapple with and theorize, this residue that authorities determined to be expendable, or even threatening, even if such engagement takes us places we would, under other circumstances, prefer to avoid.

OWS has an odor. Its lustful, repetitious, and messy imagination is articulated not only through fat felt markers on tent flaps and recycled materials, but also on naked bodies, and on moving and dancing bodies, as well as the multicellular superorganism known as the General Assembly. Still, to describe this as an archive—or swarmchive—is to suggest that OWS is more than an accumulation of conceptual, biological, and material textures. It is also something being written, call it a promissory note, an obligation to a future reader from a place already dislocated in time (though admittedly aided by time-bending cybertechnologies like YouTube and Twitter). Not what does, but what will, the archive mean, Derrida once asked, to which he then replied: “We will only know tomorrow. Perhaps.”3 Tomorrow began at 1:00 a.m. on November 15 for OWS, the hour of Zuccotti Park’s brutal erasure on orders given police by Mayor Michael Bloomberg. The NYPD raid seemed to express something else. Call it a repulsion toward damp, cardboardy smells, and commingled sweat, or a fear of the breathy exhalations emanating from the People’s Microphone, with its mandatory intervals of listening and hearing, and its uncanny pantomime of mechanical apparatus as if some inert thing were being jolted back to life. But perhaps most unsettling of all was the way OWS established a link with the dispossessed and discarded, a tactic Mike Davis perceptively contrasted to the university sit-ins of his generation in the 1960s.4 It seems that when creatives rebel, they take no hostages; they make no demands.

So there it was, occupied Zuccotti Park, filling up, hour after hour, with multiple signs of urban dispossession and homelessness, from sleeping bags to makeshift shelters, virtually everything that the “quality-of-life” city detested about the vanquished liberal welfare city, and everything it wanted to forget, including the drifters and hustlers, addicts, and graffiti taggers who are nevertheless continually generated by its deregulatory policies.5 There was no bold objective, such as forcing ROTC off campus, or establishing a Black studies program. Instead, facing inward, the OWS General Assembly painstakingly constructed systems of communication, grew antennae, spawned internal laws and methods of governance, all the while appearing from the outside to be so much dead capital, a homeless hive of unemployed kids with too much time on their (jazz) hands, growing, festering, like a blot or a bruise, directly on the belly of the global finance leviathan. Is it any wonder city patriarchs sent police to punish Richard Florida’s children turned warrior class?

ii

Village of the Damned, dir. Wolf Rilla, 1960

“Leave us alone!” asserts the towheaded cadre of mind-melded children in the 1960 British science-fiction film Village of the Damned. Mysteriously born all at once to the unimpregnated women of a rural English hamlet, the children possess collective powers of telepathy and worse. They also have an enormous appetite for knowledge. A professor played by George Sanders, the one human they tolerate and who serves as their teacher, eventually destroys them in a suicide attack. But even as the final credits roll, we never fully understand who, or what, they were. We never learn what they were after.6

iii

Police, not protestors, were visible on day one of Occupy Wall Street, September 17, 2011. They massed in all directions, ringing Wall Street, shielding storefronts, securing Citibank, Chase, Wells Fargo, and Morgan. And then there were those two, slightly chagrined officers standing watch over Charging Bull, the bellicose bronze sculpture that dominates the northern edge of Bowling Green Park. An irony likely lost on most who passed by is that artist Arturo DiModica’s giant bovine was an unannounced “gift” that he dropped in December 1989 to lift Wall Street’s downcast spirits after the crash of 1987. Initially seized by police as illegal street art, the statue was soon born-again as a seven-thousand-pound photo-op relished by tourists, filmmakers, city boosters, and anticapitalist protestors.

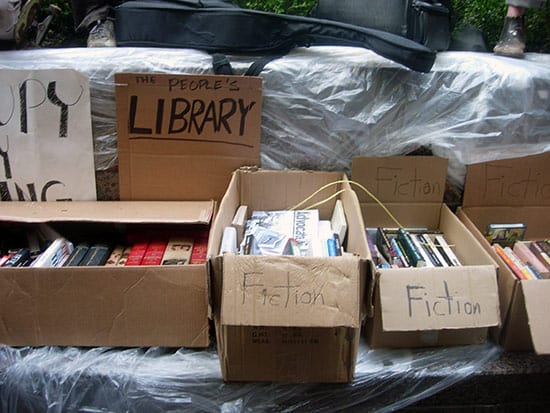

One intrepid demonstrator stood out on the first day. She carried, sandwich-board style, a photographic reproduction of Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God, the diamond-spattered platinum skull allegedly valued at over 50 million pounds. No other statement or slogan was present, as if the no longer “Y” British artist’s profligate memento mori was the indisputable portrait of our epoch. But only a few days into the occupation at nearby Zuccotti Park—the privately owned public space that demonstrators ultimately settled into after failing to take possession of Wall Street proper—a functioning commonwealth had germinated. It was complete with daily meetings aimed at self-governance; food and trash services; recycled gray-water treatment systems; a generator-powered digital media station; and an expanding collection of books and publications dubbed the “People’s Library,” nestled in rows of boxes with handwritten labels like International Relations, Music, Religion, Fiction, Non-Fiction, Feminism, and Racial Justice. (According to movement librarians, an estimated five thousand volumes were located at Zuccotti Park prior to the NYPD raid of November 15.)7 The encampment also gave life to dozens of smaller subdivisions, including Jail Support, Medics, Direct Action Painters, and one of the largest: Arts and Culture, with its own subdivisions, including Arts and Labor, Alternative Economies, and Occupy Museums. Among other immediate necessities is restoring knowledge of past attempts at organizing cultural workers such as Art Workers’ Coalition, Artists Meeting for Cultural Change, Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D), and Group Material. Much of this history has been shorn from the record to form a missing mass or cultural dark matter. The articulation of this shadow history is now taking place through teach-ins, e-mail exchanges, and archival websites, all of which are, so far, beyond the reach of police.

iv

“What do they want?” demands the mainstream media. OWS has no response. No policies, no demands, and only a stated desire to be left alone. “The 1% is just beginning to understand that the reason Occupy Wall Street makes no demands is because we aren’t talking to them. The 99% are speaking and listening to each other.”8 Zuccotti Park: Das Unheimliche.

v

Scrawled dollar signs, credit cards, monstrous octopi, mutated American flags: like pages torn from a faded copy of The New Masses (rather than Adbusters), Zuccotti Park’s artistic iconography was replete with anticapitalist slogans, clenched fists, and top-hatted millionaires.9 But this time the slogans were a great deal cheekier than those printed in the radical Leftist magazine of the 1920s and 1930s, and the fists were attached to people wearing Guy Fawkes V for Vendetta masks rather than muscular “workers.” Meanwhile, the millionaire—pulled down from his pedestal, bearded and broke—did not refer to the sketchbooks of Communist artists William Gropper or Hugo Gellert, but was appropriated straight from Parker Brother’s Monopoly board game. One sign simply implored “Occupy through Art.” Yet, despite the twenty-first-century self-consciousness, OWS released a repertoire of protest tropes that, like a grammar of dissent waiting in the wings, came to the fore as the encampment participants discovered they were legally bound to pre-electronic forms of protest. Thus there were citations, statements, manifestos, and entire letters directed to the public. “Did you lose your home? Wall Street stole from you.” One text with blue-on-red writing exclaimed tragic loss as a leftover handhold from what was once a cardboard box floated off to the side like an errant exclamation mark. Along with the ubiquitous beige of cardboard signage there were silk-screened T-shirts, a few oil paintings, and professionally designed typographic posters by Adbusters, the Vancouver-based culture-jamming magazine that first called for a Wall Street occupation on September 17. Shepard Fairey, of Andre the Giant stencil-art fame, morphed his own controversial Barack Obama election poster “Hope” into an explicit reference to Anonymous, the online hacktivist entity strongly associated with new forms of digital civil disobedience. But the President wearing a Guy Fawkes mask with the tagline “We Are the Hope” simply did not go over well with some OWS organizers. Fearing that Fairey’s graphic promoted links to the Democratic Party, the former street artist was taken to task and asked to revise his design in what amounted to a series of online studio critique-sessions: long-distance learning, OWS-style. “While it definitely looks cool, whether intended or not, this sends a clear message that Obama is co-opting OWS.”10 The movement may not have demands, but it is exceedingly conscious of its image, as befits a twenty-first-century rebellion.

vi

“i’m not a smooth writer and am barely managing to focus now on something i need to finish,” writes the Egyptian artist Maha Maamoun in an e-mail. “but in general, positions, attitudes and temperaments are changing here with every headline. its a constant tug and pull. a constant recalibration of expectations. many players rising that were not known before, and many known ones falling. its interesting to see this ‘organic’ process play out. its not easy. every detail is a battle. . . .its definitely taking a huge amount of time away from work. most of our time is spent following the news in every form. resulting eventually in loss of concentration and burnout. personally, i feel that previous drives in my work have been halted or changed. there is some kind of rupture but its not clear where exactly and what it will lead to. result is a need to be quiet and research and find one’s (new) center of gravity . . . i think activists and artists, and those who are both, are all putting in time and effort when and how they can. and since this is a prolonged situation, it is understandable that participants come in and out of action depending on their ability and time. burnout is experienced by all, and thus the need to take time out in order to be able to come back in. that is to say, divisions of roles are not so clear.”11

If a real-world crisis politicizes artists and cultural workers, sometimes to the point that they abandon their studios and galleries to engage in agitation, organizing, the production of ephemeral street art, or direct action, then is this to be understood as an aesthetic lacuna similar to a mason throwing cobblestones at soldiers, or a seamstress smuggling food to demonstrators in the hem of her skirt? Or is art’s occasional venture into radicalism something else altogether, perhaps an inescapable phase of aesthetic investigation that ironically must jettison aesthetic investigation itself (or temporarily seem to discard it)? Must it be the case that when artists take their turn along the barricades, along with the partisans and oppressed, the dispossessed and the evicted, they are there because, aside from playing for the enemy, they simply have nowhere else to go? Or are they, along with the practice of aesthetics itself, a kind of blockage or lesion found within society’s disciplinary structures, only functioning fully as a grammar of dissent in times of crisis?

vii

I visited the encampment again on October 1. Immediately following the evening’s General Assembly, OWS protestors streamed out of Zuccotti Park and swarmed up Broadway. Within the torrent of handmade protest placards—“Workers Rights are Human Rights,” “Jail Bankers, Not Protesters,” “Occupy Everything”—I spotted a trio of art students (they must have been art students), who lofted what looked like an abstract painting over their heads. Watery, colored shapes have soaked into a rectangle of beige cardboard. In truth, it was an elegantly odd picket sign that looked a bit like a DIY Arshile Gorky, and was oddly fragile, bobbing up and down in the crowd. A short time later OWS flocked onto the Brooklyn Bridge, where seven hundred demonstrators were arrested. God only knows what became of the corrugated Gorky.12

viii

Take another look at the infamous University of California, Davis, pepper-spraying video on YouTube. Watch it to the end to see the power reversal that follows the abusive violence. Students surround police. After the crowd uses the People’s Microphone, one student begins to chant, “You can go.” Others gradually follow in unison, “You can go.” You can go.” “You can go.” Like a colony of insects guided by pheromones, the police turn and march away. Applause.

ix

Capitalism, like nature, has no “history,” hisses the ghost of Milton Friedman from the great beyond. Perhaps this explains why the city of disorder—Alex S. Vitale’s sarcastic moniker for post-Giuliani New York—loathes the archive. It’s too ungainly for a town that is always investing in its present, a city that worships the erotics of gentrification and delights in the joyful liquidation of memory. In truth, this state of affairs may have been perfectly acceptable for a generation of precarious workers, artists among them. Until recently, the creative “cognitariat” demanded neither a past, nor a future, but only an opportunity to be productive all the time, 24/7, as a mode of life. That was tolerable, until capital placed its boot on the big hand of time. Suddenly both history and hope lurched into view, and memory, an archaic vestige, was foisted onto them like a millstone. Liberating the future becomes the logic of the archive, and perhaps this is why the political scientist Jason Adams argued that OWS is “increasingly complicating static images of space: it is, in short, occupying time.”13 If encampments at Zuccotti Park and other squares and public spaces around the globe marked nothing else, they marked the lawlessness of the law, or what passes for law. The real crisis is less about finance than about the social ruins that are no longer allegorical memories archaically dotting a forward-looking, modernist landscape, as Walter Benjamin held dear. Nor are they merely ungovernable disaster zones or self-contained spaces of decay within stateless states and collapsed cities. In short, ruins have become our destiny. Do you remember Occupied Berkeley and its revolt of anointed intellectual heirs decrying their education as a necrosocial graveyard “of liberal good intentions, of meritocracy, opportunity, equality, democracy”?14 Despite batons, pepper spray, rubber bullets, buckshot, tear gas, polycarbonate shields, orange dragnets, and military sound amplifiers, what has been occupied is the long duration of resistance: Trenton’s Army of Unoccupation, the Flint Michigan sit-down strike, the Woolworth cafeteria sit-in strike, Berkeley’s “plant-in” at People’s Park, an attempted occupation at New Hampshire’s Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant, the Seneca Women’s Peace Encampment, Tompkins Square “Guilianiville” in New York, as well as Seattle, Genoa, Iran, Tunisia, Egypt, Greece, Spain, Wisconsin, Wall Street—all impure, repetitive, and often self-mythologizing, occasionally sentimental, sometimes resentful, even reactionary. It is the murmur of the other archive, with its excesses, and magic gift-economies, its aesthetics of attraction, and its reanimation of dead time. Now there is only after OWS, no longer is there a prior to.

x

Immediately after the police raided Occupy Oakland, a protester spoke to a radio reporter and assured her that OWS had been dispersed for now, but would soon collect again in other locations, “like water.” Spores, buds, mushrooms, swarms, rhizomes, air, water; the swarmchive has emerged as a thing that seems to ask: What Am I? The answer is very simple: You Are the Swarmchive. You Are the Social.

—December 14, 2011

Gregory Sholette is a New York–based artist, writer, and founding member of Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D: 1980–88), and REPOhistory (1989–2000). His recent publications include Dark Matter: Art and Politics in an Age of Enterprise Culture (Pluto Press, 2011); Collectivism after Modernism: The Art of Social Imagination after 1945 (with Blake Stimson); and The Interventionists: Users’ Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life (with Nato Thompson). An assistant professor of sculpture at Queens College, City University of New York, he is involved in the experimental program Social Practice Queens, an MFA program focused on new forms of public art; he is also a member of Gulf Labor Coalition, the Institute for Wishful Thinking, and the Arts & Labor Working Group of OWS. He is currently creating a new installation for the Queens Museum of Art’s New York City Panorama, as well as cocurating with Oliver Ressler the exhibition It’s the Political Economy Stupid! for the Austrian Cultural Forum, New York. www.gregorysholette.com and darkmatterarchives.net

- See the People’s Library own archive of recent events. ↩

- Not all of the OWS proto-archive was destroyed. Some museums began collecting OWS protest signs and other material culture from Zuccotti Park before the police raid, see for example: Christian Salazer and Randy Herschaft, “Occupy Wall Street: Major Museums and Organizations Collect Materials Produced by Occupy Movement” (Associated Press), in the Huffington Post, December 14, 2011. ↩

- Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 36. ↩

- “One of the most important facts about the current uprising is simply that it has occupied the street and created an existential identification with the homeless. (Though, frankly, my generation, trained in the civil rights movement, would have thought first of sitting inside the buildings and waiting for the police to drag and club us out the door; today, the cops prefer pepper spray and ‘pain compliance techniques.’)…The genius of Occupy Wall Street, for now, is that it has temporarily liberated some of the most expensive real estate in the world and turned a privatized square into a magnetic public space and catalyst for protest.” Mike Davis, “No More Bubble Gum,” Los Angeles Review of Books, October 21, 2011. ↩

- According to the latest report by Coalition for the Homeless, the number of homeless families is now 45 percent higher than when Mayor Bloomberg first took office. ↩

- Village of the Damned was based on the novel The Midwich Cuckoos by John Wyndham, and was first made into a film in 1960, directed by Wolf Rilla, followed by a 1963 sequel entitled Children of the Damned by Anton Leader, and a 1995 remake of the original by John Carpenter. ↩

- The librarians are quoted in “Destruction of Occupy Wall Street ‘People’s Library’ Draws Ire,” The Guardian, November 23, 2011. ↩

- Editorial,“We Are Free People,” The Occupied Wall Street Journal, November, 20, 2011. ↩

- See the album of remarkably apt images from New Masses, 1926–48. ↩

- “After Conversations with Occupy Wall Street Organizers, Shepard Fairey Releases Revised ‘Occupy Hope’ Design,” Occupy Wall Street News. ↩

- From two e-mails to the author dated August 6 and August 7, 2011. ↩

- For more about painting, activism, and art education, see Gregory Sholette, “After OWS: Social Practice Art, Abstraction, and the Limits of the Social” (password-protected). ↩

- Jason Adams, “Occupy Time,” Critical Inquiry, November 16, 2011. ↩

- “Occupied Berkeley, ‘The Necrosocial,’” November 18, 2009. ↩