From Art Journal 72, no. 3 (Fall 2013)

I delivered a version of this essay as a lecture in Utrecht, on May 26, 2011, for the Performance & Philosophy working group’s panel “Enacting Pasts & Presents in Philosophy & Performance” at the Performance Studies international conference #17: Camillo 2.0. Technology, Memory, Experience. I am grateful to Laura Cull for organizing that panel, and to Esa Kirkkopelto and Brian Rotman for their comments.

I presented the finished version as a lecture at the Krannert Art Museum on February 28, 2013, in the School of Art and Design Lecture Series at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Jorge Lucero read the part of Robert, Roberta Bennet read the part of Suzanne Corkin, and Mike Parsons read the part of H.M.

– 1 –

In order to begin I must tell a horror story. I will try to mitigate the horror, through accuracy of telling, through facts, and through a degree of humility before them. Yet I will acknowledge it. I mean I already have. Horror is not fact.

It is subjective response to fact. Philosophy has a tradition of such beginning, of gleaning insight in destruction’s wake. Neurology, for its part, advances its understanding of general brain function, of memory, through the study of episodes of particular catastrophe—actual brains, actual people. Each new glimpse of memory’s claims provokes a self-correction of consciousness. Anyway, that is the story’s aspiration. It seems a meager hope to take away from the destruction of a life, or a large part of it. That hope arrived by accident, from an accident. If a way exists to soften the blows that commence in 1935, when a bicyclist collides with nine-year-old Henry, who falls and hits his head in Manchester, Connecticut, it is unknown to me and undesirable.

– 2 –

Manchester lies in Hartford County, part of Hartford from its settlement in 1672 until 1783, when East Hartford, including Manchester, separated. In 1823 Manchester became its own municipality. Thus the town in which nine-year-old Henry lay unconscious for five minutes after the bicycle collision in 1935 had the name Manchester rather than Hartford. The place’s significance to the story is less in question than its significance to philosophy. The latter we may call my question. Does philosophy have a place? Does locating it transform it into history? “Each science confines itself to a fragment of the evidence and weaves its theories in terms of the notions suggested by that fragment. Such a procedure is necessary by reason of the limitations of human ability. But its dangers should always be kept in mind.” Alfred North Whitehead said that in a lecture in 1938. By “danger” I think he meant danger to philosophy, for which such patchwork procedure, the necessary fragmentation of the sciences, might acclimate a thinker to a degree of delirium. “Philosophy is the product of wonder,” he said at that lecture’s start.1 Does wonder include horror? The subjective response to fact must remain as a precondition, if philosophy is to be its effective product. Therefore, to begin, I must tell a horror story, and to continue, I must keep the horror near.

– 3 –

At the age of ten, within one year of the head trauma sustained from the accident, Henry had his first minor seizure, called an absence, an episode described by Suzanne Corkin, a neuroscientist from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology: “He would just drop out for a second or two, and then pick up where he left off.”2 What did he drop out of, exactly? In 1942 on his sixteenth birthday he experienced his first major seizure, a generalized convulsion. Epilepsy, to seize, from medieval Latin: ad proprium sacire, “to claim as one’s own.” Epilepsy staked its claim in sixteen-year-old Henry and gripped him ever more tightly as the years passed. It delayed his graduating high school, and when he went to work as a motor winder, the increased frequency of the seizures made him give up that job, rendered any employment impossible, strained family relationships. Anticonvulsant medications carried significant side effects. As Corkin says, his “life prospects were rather dismal.” I offer all of this as setting the stage for the entrance of William Beecher Scoville, head neurosurgeon at Hartford Hospital, and not to excuse as much as to resist the temptations of judgment, to offer Corkin as exemplary of such resistance. What would I have done, I wonder, with these fragments of evidence? Where precisely in the story does the horror lie? Dr. Scoville believed he could cure Henry’s epilepsy by removing the twin parts of the frontal lobe of his brain called the hippocampus, where, he thought, correctly it turns out, Henry’s seizures originated. The cure eliminated part of his brain and part of his name, because thereafter Henry would be referred to by initials.

– 4 –

Dr. Sue Corkin will narrate now.

In 1953, when H.M. was 27 years old, Dr. Scoville performed what he called

a “frankly experimental operation” in which they removed tissue in an area toward the middle of the brain, right above the ears. This was called a “bi-lateral medial temporal lobe resection.” During the operation, Dr. Scoville made two small holes in H.M.’s skull. Through these holes he inserted retractors which he used to lift up the front part of the brain—the frontal lobes. Aspiration requires inserting a small instrument into the intended target and sucking out brain tissue. So Scoville proceeded to remove the hippocampus on both sides along with the cortex surrounding it . . .

– 5 –

The writer Richard Powers, in his 2006 novel The Echo Maker, allows a character a less equanimous rendering of the story.

One summer day half a century ago . . . an ignorant and overzealous surgeon, trying to cure H.M.’s worsening epilepsy, inserted a narrow silver pipette into H.M.’s hippocampus . . . and sucked it out, along with most of his parahippocampal gyrus, amygdala, and entorhinal and perirhinal cortexes. . . . The young man . . . was awake through the entire procedure.3

– 6 –

I do not mean to take sides in this story, if it offers sides, other than H.M.’s, or that of philosophy, to be taken. As I said at the start, the facts make their own demands of humility, of equal-mindedness. What does the taking of the side of philosophy mean after those facts and their unforgiving consequence? Their understanding necessitates their representation, and this constitutes a moment of fragmentation, to use Whitehead’s term. The telling of the story mandates a choice regarding horror, acknowledgement or disregard, and some possibility of communication and reception. Corkin’s version dispenses with horror’s recognition. The fictional neurosurgeon’s ethical outrage presupposes it. What is in the facts that either version, that any story, cannot tell? After we have named what we can name and announced what we can announce, what remains that must be demonstrated?

Corkin continues.

Scoville proceeded to remove the hippocampus on both sides along with the cortex surrounding it—areas that we know today are critical for the establishment of long-term memory. We now know that immediate memory lasts about twenty seconds. H.M. could therefore remember information for about twenty seconds before it was gone forever.

We know those things because Scoville removed those parts from H.M.’s brain. We know because H.M. survived the operation and lived out the next fifty-five years of his life. Corkin says, “The operation resulted in the patient’s losing his capacity to make new memories.” Do we make a new memory the way an assembly line makes a new car, the way Apple makes a new iPhone? Or is the phrase “to make new memories” shorthand, an analogy of sorts, and if it is how do we take the measure of the appositeness of the image it evokes relative to the complex set of actions that it indexes? “We must first make up our minds whether time is to be found in nature, or nature to be found in time.”4

– 8 –

Whitehead considered philosophy the practice of bringing the knowledge of a spectrum of disciplines into alignment with the most advanced among them; so taking the side of philosophy might mean a refusal to fall victim to fragmentation, despite necessity. All must contend with the advances of the others. Another way to say it is, “Philosophy has no knowledge of its own.”5 It has only methods for reconciling the knowledge amassed by other fields. By knowledge I mean aggregates of facts and feelings. I offer this as explanation for the inclusion of two versions of the Scoville procedure. Corkin’s version describes the event in layperson’s language that retains the accuracy of the medical discourse, including acquiescence to its rationalization. The Powers version gives the floor to a fictional mouthpiece who feels few qualms in objecting. The two versions might be said to agree on two propositions. The first is that a second force had claimed a grip on H.M.’s existence, and unlike the first force of the bicycle collision with its resulting rhythms and pressures of epilepsy, this second force would never have occurred by accident. Under no imaginable circumstance could Henry have lost possession of those particular parts of his brain other than the circumstance that he found himself in, as a test subject, of that doctor, at that moment, in that place. That is to say, while the bicycle accident could have happened on any American street, the surgery could only have happened in Hartford in 1953. The second proposition is that we do not know how the present becomes the past, but we do know when, and that is after twenty seconds. The proof of this arrives by way of the observable toll on a human subject. In order to contend with that toll, its facts, and its feelings, philosophy must demonstrate a precise knowledge of what we now call the present. By demonstration I mean the construction of a sharable experience. In so saying, I will not be the first to point out parallels between this task and that of poets. The necessary first question for an understanding of memory and what its collapse reveals is: what is twenty seconds?

– 9 –

One enters the installation titled H.M. by the artist Kerry Tribe through a bright room on the way to a darkened room. The bright room houses two projectors at work, with one film scrolling between them, first through the projector on the left, then across the space of the room and through the projector on the right.

In the darkened room, one sees a screen with the two images running in parallel, projected through a window from the bright room. If one stays for twenty seconds or longer, one may realize that the right image is the time-delayed repetition of the left image. A calculation has apparently been made, one realizes retroactively, that determines the distance between the two projectors back in the bright room as that which will delay the repetition by precisely twenty seconds.

What appeared on the left appears on the right twenty seconds later, with its sound muted but audible. One might have the sense that the image has been traveling for that twenty seconds, silently and invisibly, as the film travels, until it arrives on the right screen, slightly diminished. The image travels like time on a timeline diagram, from left to right, like reading.6

As the left image advances, one might try to retain the sense of that advancement in order to predict what will happen next on the right. At times the appearance of the image on the right is so unexpected that the viewer might think: If I had not seen the physical loop in the bright room, I would believe I am seeing two films. The left image was instantly forgotten, or it passed unnoticed, or its reappearance in juxtaposition with a new left image has completely transformed it. These are the possibilities.

Another phenomenon takes shape in the duration of the twin projections that one might consider interference, or the aggregation of the two projections into a dialogue that does not seem accidental.

– ∞ –

“What we perceive as present is the vivid fringe of memory tinged with anticipation. There is no sharp distinction either between memory and the present immediacy or between the present immediacy and anticipation. The present is a wavering breadth of boundary between the two extremes.”7

– 10 –

The left image states its case as it goes. But when that statement returns, it seems to return as both repetition and as comment on the statement now being made, twenty seconds later. The present is not the left image alone, but both images aligning, as well as the perception of the gap between them.

The present becomes a twenty-second slice of time, bookended by the advancement of the lead apprehension, shall we call it, and the disappearing echo of that apprehension twenty seconds later, which is to say the present includes a recognizable margin of the near past, just as it vanishes into the less-near past. That vanishing, as well as the apprehension of the present in demonstration, makes a guess at something of the experience of the adult life of H.M.

We know this because that life constitutes the subject of the film. The offering, in both the bright architecture of a memory theater and that theater’s darkened, immersive result, comes to us as an instance of analogy. The effects of the analogy include a disorienting and empathic recalibration of reason—a self-correction of consciousness—constrained by the twenty-second measure of the present.

– 11 –

I have borrowed the phrase “effects of analogy” from another resident of Hartford, Connecticut, the poet Wallace Stevens, who used it as the title for a lecture he delivered at Yale in 1948. Here is an excerpt:

When St. Matthew in his Gospel says that Jesus went about all the cities, teaching and preaching, and that “when he saw the multitudes, he was moved with compassion on them, because they . . . were scattered abroad, as sheep having no shepherd,” the analogy . . . is not emotional. On the contrary, it is as if Matthew had poised himself if only for an instant, had invoked his imagination and had made a choice of what it offered to his mind, a choice based on the degree of appositeness of the image. He could do this without being notably deliberate because the imagination does not require for its projections the same amount of time that reason requires.8

– 12 –

Whitehead asserted that “creativity is always found under conditions, and described as conditioned.”9 Maybe creativity, like philosophy, has no knowledge of its own. By creativity I mean acts that combine or recombine instances of perception. The value of the combinations lies in the actuality that conditions them. We can understand Tribe’s installation as the result of a creativity that responds to the conditions of H.M.’s adult life to the extent that those conditions are transferable. By transfer I mean migration, as from one medium to another, the same sort of upgrade I had in mind as the domain of philosophy, as reconciliatory of a range of thought and investigation—an elaborate act of analogy. Analogy, from the Greek: analogos, “proportionate,” literally, “up” + “word,” up to (the limit of) the word, the image at the edge of language. Two rooms, two projectors, one film threading through a twenty-second delay—like St. Matthew’s sheep with no shepherd, the structure does not require for its projections the same amount of time that reason requires. Condition reason in proportion to the actual to quicken it. The reach of its shape is apposite first, emotional second; it yearns for accuracy. Stevens christens analogy a “discipline of rightness.” Then he turns to Whitehead.

The imagination [is] a power within [the poet] to have such insights into reality as will make it possible for him to be sufficient as a poet in the very center of consciousness. This results, or should result, in a central poetry. Dr. Whitehead concluded his Modes of Thought by saying: “The purpose of philosophy is to rationalize mysticism. . . . Philosophy is akin to poetry, and both of them seek to express that ultimate good sense which we term civilization.”10

– 13 –

Is the center of consciousness, the place of the poet, like the center of the brain, the place of the hippocampus? Elsewhere, Whitehead wrote of philosophy’s role in the creation of the future. Philosophy, akin to poetry, centers on a continuum, and “in each case there is reference to form beyond the direct meaning of words.”11 If we claim a kinship between philosophy and poetry, we must note a relation between the product of wonder and that of rightness. Maybe “form beyond the direct meaning” is the proportion of the actual that constrains meaning, that speeds its transit. Wonder, the companion of rightness, follows its lead. I hear an echo of the passage by Stanley Cavell that produced the phrase I have been leaning on.

The task of description, of some so far undefined species, is more fundamental to philosophy, or constant in it, as I care about it most, than the tasks of explanation or argument. Since philosophy has no knowledge of its own, its power must lie in uncovering obviousness, in a sense becoming undeniable.12

At the moment, the obviousness that I aim to uncover I might call neighborliness, or, with a nod to a Cavellian notion derived from Thoreau’s Walden, nextness; that is, to accept the subtle, insistent relation between the closest of neighbors in order to endow proximity with enduring significance, as a minor instance of “that ultimate good sense which we term civilization.”13

– 14 –

On the soundtrack of Tribe’s H.M., Corkin describes something of her childhood.

I grew up in West Hartford, Connecticut. One of my best friends lived across the street from me. Our houses had matching floor plans. We used to walk to school together, play hopscotch together. We even made a walkie-talkie with two tin cans connected by a string that spanned the street. My friend told me that her father was a neurosurgeon but I had no idea what that meant.

Years later, I found myself reading about a brain operation my friend’s father performed on a young man trying to cure his epilepsy. The operation resulted in the patient’s losing his capacity to make new memories. My friend’s father was William Beecher Scoville, and the patient was H.M.

The Book of Deuteronomy says that on the children are visited the iniquities of the parents. To the extent that some version of that remains true, and as long as children grow up across from nearest neighbors, all philosophy will happen someplace. This is my proposal, an attempt at a rationalization of mysticism of a sort. The philosophy that finds its way to us today from Hartford, Connecticut, issues from a horror story. A flick of God’s finger starts a particular world spinning. Another way to say it might be this sentence from Stevens’s “Effects of Analogy”: “For each man, then, certain subjects are congenital.”14

– 15 –

“I met H.M. in 1962,” continues Corkin, “when I was a graduate student. Beginning in 1966 H.M. used to travel up to MIT to the Clinical Research Center where my colleagues and I would test him. So I’ve known him since 1962 and he still doesn’t remember who I am.”

The film reenacts the dialogue that leads Corkin to this conclusion.

SUE CORKIN (VOICE OFF)

Have we met before, you and I?H.M.

Yes, I think we have.SUE CORKIN (VOICE OFF)

Where?H.M.

Well, in high school.SUE CORKIN (VOICE OFF)

In high school!H.M.

Yes.SUE CORKIN (VOICE OFF)

Have we ever met any place besides high school?H.M.

Now I don’t . . . no, I don’t think so.

– 16 –

The neurologist Israel Rosenfield wrote on the case in 1992.

Brenda Milner and W. B. Scoville reported in 1957 that following the surgical removal of an area of the brain called the hippocampus, a patient, H. M., lost recent memories but retained long-term ones. . . . This discovery led to a number of suggestions about how the hippocampus was crucial in the brain’s converting short-term memories to long-term memories. By the 1970s, however, these ideas were abandoned and replaced with other models. . . . It was argued, for example, that the meanings of words and other verbal symbols are stored separately from memories of personal experiences, and that verbal memories enter long-term storage directly, bypassing the short-term memory mechanisms. Oddly, nobody considered that these different kinds of memory might be interrelated and that the neurological “evidence” that they were independent was based on a presumption that when the patient named an object, the name meant to him what it meant to the examiner. The profound changes in the patient’s subjective world were overlooked, especially the deepest clue of all: the patients had lost the sense of time. What did it mean for a patient to “recall” an event from his distant past when he had little or no idea about the present? Even the apparently objective naming of objects was unreliable. What, for example, does a “clock” mean to a patient who has no real sense of time? . . . Not only do objects have temporal associations, but “what they are” to a person cannot be separated from a person’s notion of time.15

That is to say, when H.M. says “high school” how can he possibly mean what Corkin means when she says “high school”?

– 17 –

Rosenfield also wrote:

The hippocampus is closely linked anatomically to parts of the brain that regulate the body’s internal mechanisms such as heartbeat, digestion, and respiration; one might then quite plausibly argue that injury to the hippocampus, in destroying the relation between external and internal stimuli, destroys the ability to create a “memory” that will have a meaningful relation to the self. But long-term memories just as much as short-term ones . . . are created in reference to the self whose memories they are. In what ways is the “self” with long-term memories different from (or similar to) the “self” of short-term memories? Perhaps more important, can we really describe these “selves” as independent? Surely they must depend on each other. The “self” linked to time past is an abstraction of the self-referential “I” that establishes immediate relations to its surroundings.16

– 18 –

Rosenfield challenges the definition of memory as information storage, considering it instead the ongoing restructuring of oneself in relation to patterns of the changing continuum of the present; that is, the capability to imagine a consistent self, legible to consciousness, in a complex network of relations. Another way to understand Rosenfield’s reframing of H.M.’s condition might be to ask why eliminating the capacity to make a new memory also eliminates the capacity to trigger a seizure. What is the relationship between epilepsy and memory? Why does seizing the moment, claiming it on a continuum with the moment just past, share a neurological neighborhood with the seizing up of the body, the dropping out of the mind? Scoville’s cure for dropping out rendered that condition permanent—as a loss of the temporal link between physical sensations from one moment to the next. Remove the body as continuous point of reference, and there can be no temporal flow. With the loss of continuity of brain function comes the loss of the continuity of time.

– ∞ –

“The mere fact of memory is an escape from transience. In memory the past is present. It is not present as overleaping the temporal succession of nature, but it is present as an immediate fact for the mind. Accordingly memory is a disengagement of the mind from the mere passage of nature; for what has passed for nature has not passed for the mind. It is impossible to meditate on time and the mystery of the creative passage of nature without an overwhelming emotion at the limitations of human intelligence.”[17 Whiteread, Concept of Nature, 68 and 73. ]

– 19 –

A boat ferries a selected load from the near shore of now across the river of time and deposits it on the far shore of then, and returns for another. The boat is called hippocampus, Latin for “sea horse,” since that fish is what the anatomist Julius Caesar Aranzi thought the shape of that little piece of the brain resembled when he named it in 1564. He adopted the name from an imaginary creature of Etruscan mythology, the hippocamp, with the foreparts of a horse and the hindquarters of a fish; these creatures pulled the carriage of Poseidon, god of the sea and of horses, across water and land alike. But H.M. has no hippocampus now. Like the famous geese observed by Konrad Lorenz, “The death of one member of the pair leads to a search for the missing partner that can last for days. So the brain is searching for a solution to problems that cannot be solved.”17 Something has vanished from the brain’s ecology, and now this brain’s life is defined by a search for the unfindable. How can the brain conceive of that loss? It no longer has seizures, but neither does it connect itself to time. In fact both shores seem equally distant now, equally obscure. The mind stands in the river, and the river is a film that keeps running. It runs on one shore twenty seconds before it runs on the other. The imperative urge is to find the missing pieces. They must be here somewhere. The ferry has simply capsized. It might yet be raised and brought back into working order.

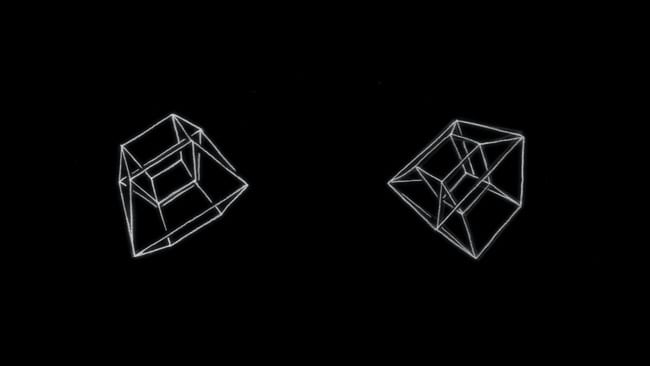

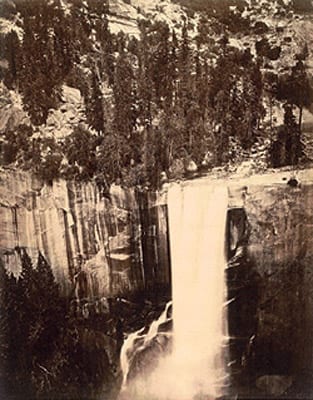

Or say it this way. The quality of H.M.’s consciousness that Tribe’s installation captures is not precisely the loss of time, but the loss of the capability to place the self in relation to time. The lost ability to grasp the elusive near-at-hand as it passes by leaves the impression of a possibility of grasping, of repair, or of relearning the missing skill, dimly remembered. So the search continues, the search that looks like a loss of short-term memory, and all life becomes searching—for time, pattern, self, twin sea horses. The film keeps running, echoing itself. Near the end, a voice-over states, “Those who know H.M. report that he’s always observing them, trying to gauge what is expected of him, what is appropriate. What would it be like to live without recourse to the past? . . . Time would not be linear and fixed but liquid. Malleable.” The image shows an animated rotating tesseract, an attempt at a linear illustration of the four-dimensional shape analogous to a three-dimensional cube. It seems a peculiarly mathematical choice, yet one that suggests the limits of the human mind. Another filmmaker, Hollis Frampton, once invoked the tesseract in describing a wet-plate collodion photograph from the 1870s by Eadweard Muybridge, of a Yosemite waterfall, “long exposures of which produce images of a strange, ghostly substance that is in fact the tesseract of water: what is to be seen is not water itself but the virtual volume it occupies during the whole time-interval of the exposure.”18 The visual trace of the time passing speaks to the capacity to hold duration in the mind as a four-dimensional manifold, like the volume bracketed by Tribe’s twin projections. The effort to sustain such volumetric perception raises questions of the shifting subjects within the work’s analogous shifts of reception: When we step into the stream of this work, what responsibility do we accept? Who can we be said to become? A double answer offers itself, reflecting the work’s dual degrees of immersion. In the dark room, I am the patient; in the bright room, the doctor. A horror story unfolds. I may step into it. I may step out of it. In one place I am a scientist, constrained by ethics. In another I am a philosopher, subjected to horror, to wonder, to overwhelming emotion. In a third, at some remove, I become a poet, attuned to rightness. The choice is mine.

– 20 –

SUE CORKIN (VOICE OFF)

You like to do crossword puzzles, don’t you?H.M.

Yes, I do.SUE CORKIN (VOICE OFF)

Why’s that?H.M.

Because sometimes I remember words. And sometimes I don’t have to look them up. I remember them.SUE CORKIN (VOICE OFF)

You are terrific at remembering words.H.M.

Well . . . I used to do them too, before I was sick and everything.SUE CORKIN (VOICE OFF)

And what kind of sickness was it?H.M.

They called it “epilepsy” at the time.SUE CORKIN (VOICE OFF)

And how did it affect you?H.M.

Well, I knew that if I had it, it would be cured sooner or later. And that’s just what I had to look forward to, in a way. I knew they would do something to me and I would be cured. And get my—well, parts of my memory back.

After repeated trials on the same crossword, H.M. would sometimes learn to fill in the right answers. For a time, he would retain factual post-1953 information. Corkin suggested that this learning involved weak signals from brain tissue around the missing hippocampus. 19 Most notable perhaps are H.M.’s repeated attempts, his crossword practice, as if other parts of the brain could acquire the skills of the hippocampus. “Appetition,” noted Whitehead, “is immediate matter of fact including in itself a principle of unrest, involving realization of what is not and may be.”20

– 21 –

“Consciousness is dynamic, and memory is part of the dynamics of consciousness.”21 With each retrieval of a fact, there is an updating and reshaping of that fact, and a corresponding process of continual reconsolidation of the self. To make a new memory is to make a new self. H.M. remained stalled at the brink of this process, and the post-1953 crossword answers faded. What is lost with the loss of one’s relation to time is process itself, the becoming of experience. A further problem then arises. If the recollection of each so-called long-term memory relives that memory, or remembers it as if for the first time, as if it were a new memory, and if H.M. has lost the neurological capability to make new memories, then even the old memories will degrade over time. What becomes of the past without the present?

MALE V/O

While H.M.’s declarative memory from the years prior to his surgery in 1953 appears to be largely intact, scientists were surprised to discover that, in recalling his own past, H.M. appeared to be reporting the gist of things that he knew to have happened, rather than reexperiencing or reliving his life.INT. CORKIN LAB, MIT, 1992—DAY

SUE CORKIN (VOICE OFF)

And what is your favorite memory that you have of your mother?H.M.

Well, that she’s just my mother.SUE CORKIN (VOICE OFF)

But can you remember any particular event that was special?H.M.

Of course, she’s my mother.

– 22 –

What words remain at the end of the imagination, in the dream of the present without a past? I look down and find myself dressed in something like a hospital gown, and:

all the skill I have

Remembers not these garments.I think I should know you.

I say to my daughter. And then:

You are a spirit, I know: when did you die?

But she is not dead, although she will die soon, and then I will cradle her in my arms, and will oddly exclaim:

my poor fool is hang’d!

I have not found a satisfactory explanation for the strange last moments of King Lear. Why refer to his daughter as his Fool? I am partial to one historical theory. In the original production, the same actor played both parts. It is true that Cordelia and the Fool never occupy the stage simultaneously, and do not share a single scene. Let’s say Shakespeare folded that doubling into the writing, into Lear’s delirium, and his search for sense, that is, for the past, in the fragmentary present. As Rosenfield writes, “To make a distinction between long- and short-term memory or between abstract and immediate knowledge may be useful clinically, but . . . we must try to understand that our relation to the world is not ometimes abstract and sometimes immediate but, rather, always both.”22 Wallace Stevens wrote a poem titled “A Clear Day and No Memories.” It begins with a line worthy of Lear: “No soldiers in the scenery. . .” The late poem was included in a posthumous collection. Posthumous indeed; “after earth.” What words remain at the end of the imagination, in the dream of the present without a past? Think of the Fool as Cordelia, repeated at something like a twenty-second delay. What might that formulation allow to appear?

– 23 –

At the end of H.M. Tribe confronts us with the remarkable texts of H.M.’s sleep studies. Tribe wrote me:

Everything that is said in my film is historically accurate (i.e., H.M. really said all those things). . . . I did work very closely with Suzanne Corkin (that is her in the voice-over—not an actor), and she generously shared transcripts of these “inconclusive” sleep studies you asked about. They are “inconclusive” because it’s not known if he’s really reporting dreams, as he claims, or memories from before his procedure. I chose to use those particular reports . . . because they seemed allegorically significant in relation to my project.23

In one such dialogue, H.M. denies he is either dreaming or remembering. He says he is simply thinking.

– 24 –

H.M.

What’s the matter?ROBERT

Were you dreaming?H.M.

No.

Where is this?INT. SLEEP STUDY FACILITY, MIT, 1977—NIGHT

ROBERT

You’re at MIT.H.M.

Huh?ROBERT

OK. You didn’t dream.H.M.

No. Thinking.ROBERT

What were you thinking then?H.M.

The thought I had . . . well, was I was causing interference? . . .ROBERT

Where?H.M.

Well, in the machine. It would be a combination of one thought being twice. Of course, it was the same thought right next to itself, you might say.ROBERT

What is it you’re talking about now?

Are you talking about the electrodes?H.M.

Just putting it on, and a double put-on one time. One side was put on but the other wasn’t. That’s what I mean by the double.ROBERT

OK. But you weren’t dreaming.H.M.

No.

– 25 –

How is this dialogue possible? Could H.M. dream the image and describe it within the span of twenty seconds? Or could he retain a (clairvoyant) pre-1953 thought so lucidly? One is tempted to propose a new category of memory that makes itself known from associations, dreamlike if not exactly dreams. However irrational the facts, elusive the feelings, and inchoate the expression, the thought and the thinking we recognize as beginning from the place of the poet or philosopher. That is to say, if only for a moment, H.M. appears to grasp a sense of self in relation to time, reconfigured through the effects of analogy. This self speaks as from the double bind of being an object of scrutiny, trying to gauge what is expected of him, constantly being asked: Who are you in time, this time? So we may ask in the end: where precisely can we place the horror of the story? It is clear by now that H.M. has no sense of horror as such, only of a new chance of life. He does not tremble before his fate, but strives to overcome it. We look at any part of the story, and horror recedes from it. Yet we know it is there, and will remain there, at least for us. We sense it as we place ourselves in these rooms, as if we can inhabit memory and its rupture at once. This work grants us this superhuman license even as it submits us, like H.M., to tests of perception. It asks us to try to keep pace with the twenty-second tesseract of the present, continually unfolding from itself, folding into itself, and disappearing. This test is an extended act of empathy. In the dark room, in H.M.’s place, we perceive in a way analogous to his perception. The present on display is not any present, but a version of his life, analyzed, explained, and depicted. Is this recursion—of a life watching itself watching, or a mode of watching watching the explanation of itself as a mode—a further test of empathy, of H.M.’s double bind, the life lived in infinite regression?

– 26 –

We experience this work as a violence done to time, a machine to prevent the formation of a coherent self. The ordeal awakens the anxiety of the question of how, or where, we can invest such an unsettled self in any act in the present. The film ends with Corkin’s statement that H.M. “has never been filmed, photographed, or videotaped.” We have been watching an uncanny portrayal by an actor (Darrell Sandeen), as well as a series of reconstructions of scenes, drawn from medical transcripts. Something of the science project becomes apparent now. A distancing effect draws this impossibly private struggle for existence into communal forum, as if to share the unsharable. Maybe this is precisely what has returned these facts to horror’s orbit: not horror-in-general but this horror, always only apparent in relation, in duration, in motion.

– 27 –

“Consider a Christian meditating on the sayings in the Gospels,” wrote Whitehead. “He is not judging ‘true or false’; he is eliciting their value as elements in feeling.”24 If modern neurology has a gospel, it is the book of H.M. Tribe’s work uncovers its value beyond the disturbing and baffling facts and their contested theories and propositions, in what haunts and animates them—less in what they tell than in what they demonstrate. To realize them is to admit them into feeling: of wonder in the presence of time as it passes, of horror at the dissolution of the self. In dreams at last, call them “sleep studies,” or in analogy, the human intelligence can still escape its limits, and fabricate—from the matter-of-fact of its own absence—reprieve, or even, to some degree of rightness, redemption.

– ∞ –

A Clear Day and No Memories

No soldiers in the scenery,

No thoughts of people now dead,

As they were fifty years ago:

Young and living in a live air,

Young and walking in the sunshine,

Bending in blue dresses to touch something—

Today the mind is not part of the weather.Today the air is clear of everything.

It has no knowledge except of nothingness

And it flows over us without meanings,

As if none of us had ever been here before

And are not now: in this shallow spectacle,

This invisible activity, this sense.25

Matthew Goulish is dramaturg for Every house has a door. His books include 39 Microlectures (Routledge, 2000), The Brightest Thing in the World (Green Lantern, 2012), and Work from Memory, a collaboration with the poet Dan Beachy-Quick (Ahsahta, 2012). He teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

This essay originally appeared in the Fall 2013 issue of Art Journal.

- Alfred North Whitehead, “Nature Lifeless,” in Modes of Thought (1938; New York: Free Press, 1968), 131 and 127. ↩

- Suzanne Corkin quoted in Kerry Tribe, H.M., unpublished screenplay, 2010. All further quotations of Corkin and of her dialogues with H.M. are from Tribe’s text. Since the completion of Tribe’s installation and the writing of this essay, Dr. Corkin has published her definitive account of Henry’s case. It will clearly become a key source in the literature, and many passages from Tribe’s screenplay occur almost verbatim in the book: Suzanne Corkin, Permanent Present Tense (New York: Basic Books, 2013). ↩

- Richard Powers, The Echo Maker (London: Random House, 2006), 359. ↩

- Alfred North Whitehead, The Concept of Nature (Cambridge, UK, New York, and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 65. ↩

- Stanley Cavell, Little Did I Know (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010), 65. ↩

- My college philosophy professor, Dr. John B. Spencer, lingered on the question of how to diagram time’s movement, or direction, in his representations of Whitehead’s speculative process philosophy. Some languages are read from right to left, others from top to bottom, but a line of the major cultural language of the United States, English, as well as one in most mathematical equations, is read from left to right. This therefore determined the direction of time on a chalkboard in our classroom in the year 1981, but not without due consideration, which seems relevant to the movement of the film in Kerry Tribe’s H.M. ↩

- Whitehead, Concept of Nature, 73 and 69. ↩

- Wallace Stevens, “Effects of Analogy,” in The Necessary Angel (New York: Vintage Books, Random House, 1951), 113–14. ↩

- Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York and London: Free Press/Macmillan, 1978), 31. ↩

- Stevens, 115. ↩

- Whitehead, “The Aim of Philosophy,” 174. ↩

- Cavell, 250. ↩

- Stevens, 116. ↩

- Ibid., 120. ↩

- Israel Rosenfield, The Strange, Familiar, and Forgotten: An Anatomy of Consciousness (New York: Knopf, 1992), 70–71. ↩

- Ibid., 71. ↩

- Israel Rosenfield, The Invention of Memory: A New View of the Brain (New York: Basic Books, 1988), 65. ↩

- Hollis Frampton, “Eadweard Muybridge: Fragments of a Tesseract,” On the Camera Arts and Consecutive Matters: The Writing of Hollis Frampton, ed. B. Jenkins (Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 2009), 27–28. ↩

- See Benedict Carey, “No Memory, but He Filled in the Blanks,” New York Times, December 7, 2010, D3, online at www.nytimes.com/2010/12/07/science/07memory.html (as of October 9, 2013). ↩

- Whitehead, Process and Reality, 32 and 166. ↩

- Rosenfield, The Strange, Familiar, and Forgotten, 140 and 107. ↩

- Ibid., 80. ↩

- Kerry Tribe, e-mail to the author, November 20, 2010. ↩

- Whitehead, Process and Reality, 185 and 188. ↩

- “A Clear Day and No Memories” from Opus Posthumous: Poems, Plays, Prose by Wallace Stevens, copyright © 1989 by Holly Stevens. Preface and Selection copyright © 1989 by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC. Copyright © 1957 by Elsie Stevens and Holly Stevens. Copyright renewed 1985 by Holly Stevens. Used by permission of Vintage Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC.

All rights reserved. ↩