Oblivion to me is a state when you’re not conscious of the time or space you are in….Places without meaning, a kind of absent or pointless vanishing point.

–Robert Smithson, “Fragments of a Conversation” (1969)1

The apologists for “Big Data” seem to be everywhere these days. In forums ranging from TED talks to marketing campaigns, we are now being bombarded by the just-on-the-horizon possibilities of Total Information. It is no surprise that a particular articulation of these ideas has also surfaced in the world of contemporary art practice. With the promise of accessing a Borgesian map composed of digital data, artists and composers are newly attempting to translate information at a sublime scale for visual and auditory consumption. We may think of these works, animated by evolving visualizations of seismic, atmospheric, or demographic data, as groping toward a new kind of geography, a new way of writing and picturing the world as such. While these projects certainly transcend the boundaries of the self-conceived art world, this discussion will focus particularly on those for which the primary site of reception is a gallery context. This is not to suggest the irrelevance of other examples, but rather that the larger culture of data analytics receives a particular kind of expression when figured as part of an artwork. This narrowed frame allows us to understand the larger stakes of the new data Weltbild all the more clearly.

Artistic data visualizations have indeed become almost ubiquitous within the last few years. While web-based works such as Aaorn Koblin’s Flight Patterns or Fernanda Viégas and Martin Wattenberg’s Wind Map have gained enormous followings through social media channels, other, more traditionally object-based installations have brought large-scale mapping into the space of the museum. One of the first of the present generation of projects is The Place Where You Go to Listen (2008), an installation at the Museum of the North by the Pulitzer Prize–winning composer John Luther Adams that translates information about local geological activity into a constantly shifting visual and auditory environment. More recently, Jana Winderen’s Ultrafield, a sixteen-channel soundscape of the northern waters, represented sonic geography at MoMA’s 2013 Soundings exhibition, while Greg Niemeyer’s Polartide, a visual/aural representation of the data concerning the world’s ocean levels and the profits of the world’s largest oil companies, was on view at the 2013 Venice Biennale. Though one could certainly work toward a more comprehensive list, the projects of artists ranging from Mark Hansen and Ben Rubin to David Bowen, Daniel Crawford, Terreform Studio, Shawn Brixey, and Matt Roberts represent a partial sample of the work being done in this terrain.

While these works address themselves primarily to pressing, contemporary issues—the pervasive sense of disconnection from the natural world, the imminent threat posed by global warming, and of course the rise of Big Data—I would argue that to understand the grammar and ultimately the meaning of these gestures it is necessary to remove them from the immediate present. As a corrective to the kind of presentism that can all too often dominate discussion of this field, this project will present three case studies, unfolding from September to December 2014, that pair contemporary investigations with relevant antecedents. Though much of the work is characterized by a digital cleanness that would have been anathema to earlier producers, many of the most significant predecessors of this new geography can be found in the ferment of the 1960s. While composers such as La Monte Young and Robert Watts sought to transform the processes of the earth into open-ended and largely unauthored pieces of music, other artists such as Nam June Paik envisioned the technological interconnection of the world as a means to bring about the dawning of a new global consciousness. However, the imbrication of contemporary practice within this trajectory of transparency and harmony enables us to see how “the new geography” tends to distance itself from other, potentially relevant histories. Whereas the above projects were animated by a notion of coherence and legibility as underpinning the structure of the world, the work of artists such as Mel Bochner and Robert Smithson were predicated on the idea that the world as a system may not be fundamentally coherent, and it is certainly not legible within its own terms.

The forgetting of the critical distance between terrain and data, between site and non-site, may not be an entirely fair criticism to lay at the feet of practicing new media artists. The computer, after all, is particularly suited for what Bruno Latour has described as “drawing things together,” gathering dispersed sets of information and translating them so that they may be compared with one another2. Nevertheless, the key insight provided by the critical artists and writers of the 1960s is that to arrogate to our own conventions the ability to grasp “the world as it is” is a kind of anthropocentric blindness. What we need is an art, as well as an art theory, that reveals the hidden rhythms of the globe while also pointing toward the contingency and historicity of our present means of picturing them.

Paring 1: John Luther Adams’s The Place Where You Go to Listen (2009) / Robert Watts’s Cloud Music (1974)

Occupying a dedicated gallery at the Museum of the North at the University of Fairbanks since 2008, Adams’s The Place takes input from a wide array of meteorological, atmospheric and seismic activity, and translates it into an evolving visual and auditory installation3. While glass panels that change colors according to the time and season are the main visual elements, the primary sonic features are the Day and Night Choirs—clouds of evolving major-scale tones that shift according to the external light. Bracketing the choirs are the Earth Drums, a set of deep, pulsing bass tones that are regulated by local seismic activity, and the high-pitched Aurora Bells, which capture the pulsing movements of the magnetic field that cause the Northern Lights. The overall effect of the work is akin to a dynamic version of the intermedia presentation of Morton Feldman’s music at the Rothko Chapel in Houston—a diffuse, ethereal evolution of chromatic and tonal clusters that seeks to cultivate a sense of contemplative stillness in viewer-listeners4.

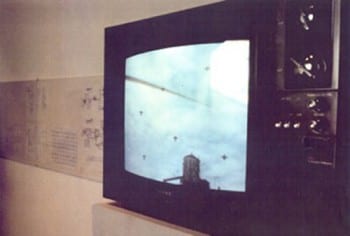

While the technology and the ambition of Adams’s work mark its difference, his process of music generation via meteorological input is remarkably parallel to that employed by Robert Watts in his 1974 Cloud Music. Produced in collaboration with the video engineer Bob Diamond and the electronic music pioneer David Behrman, Watts’s Cloud Music built on the interest in art/science pervasive at the tail end of the 1960s. While John Cage had produced music by intercepting random radio waves at the Experiments in Art and Technology Evenings, Watts’s piece aimed for a soundscape generated by arbitrary sampling of natural rather than technological artifacts. A work that is both an experimental musical composition as well as a performative sculpture, Cloud Music was composed of a camera pointed at an open patch of sky, a video analyzer that follows the fluctuations in sky brightness, and a custom electronic sound synthesizer that generated de novo music from input coming from the video analyzer5. Six speakers, mounted around a video monitor displaying the live video feed, play an ongoing set of ethereal, ambient tones—reminiscent of the electronically inflected drone of La Monte Young’s music—that subtly shifts in response to passing clouds6.

Cloud Music is in many ways a striking precursor to Adams’s The Place. Both pieces capture and analyze information about the Earth’s natural flux, and translate data into coordinated auditory and visual presentation. These installations, whether they may seek to expose their inner workings like Cloud Music or attempt to present a seamless exterior like The Place, emphasize both the liveness of the data and the lack of intentional, authorial orchestration of the material presented. However, questions of intention and meaning point to subtle but nonetheless important distinctions between the pieces. For Adams, the site of his installation—and its connection to a set of Native American histories—has important ramifications for how The Place is to be understood. The title itself derives from an English translation of Naalagiagvik, a place on the coast of the Arctic Ocean where, indigenous traditions holds, an Inupiaq woman could go to hear and understand the soundscape of the natural and supernatural worlds7.

In essence, Adams’s The Place seeks a return to this condition of geological, ecological, and spiritual comprehensibility. Though the wider arc of his composition is structured by a fascination with the way in which wild spaces register certain rhythms and textures, the installation at the Museum of the North represents an insistent, almost mystical faith in what we might describe as the legibility of the local. As the Inupiat had Naalagiagvik to tap into the deeper alignment of the world as expressed in sound, museumgoers have The Place to absorb the earth’s processes, reproduced as visual and aural harmonies. By contrast, Cloud Music foregrounds its visual and sonic arbitrariness. The sounds it generates are not intended to reveal a truth about the clouds that pass in front of its lens. Rather, the clouds serve as a means of “disauthoring” the music, of allowing a chance procedure to produce aesthetic results without top-down interference from a “composer.” The difference, in essence, is between a creation that holds the Earth’s processes as a means of randomization and one that understands them as means of signification.

A specially designed video system scans the sky. An electronic sound system translates changing cloud formations into music.

This question, of the semantic possibility of the world as such, was extremely important to the larger intellectual history of the 1960s. Longstanding beliefs in the communicative potential of the natural world, exemplified in this discussion by the Inupiaq legend of the Naalagiagvik, appeared increasingly untenable in a postatomic, postexistential culture that held mankind to be fundamentally alone in the universe. This shift was articulated in any number of places, though one of its clearest expressions was in the writings of the French novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet. “The world around us,” insisted Robbe-Grillet in 1963, “once again becomes a smooth surface, without signification, without soul, and without values, on which we no longer have any purchase.”8 While Robbe-Grillet’s charge—for cultural producers to come to grips with the fundamental incommunicability of the environment—was taken up by a significant number of artists, the work of Mel Bochner and Robert Smithson is particularly germane to the present history of artistic attempts to know and picture the world in toto.

The next pairing in this series will be Jeremy Wood’s The Permissible Edge (2013) and Mel Bochner’s Measurement Room (1969)

Mike Maizels is teacher, curator, and scholar interested in the long tail of the artistic innovations of the 1960s. His first book, forthcoming from the University of Minnesota Press, focuses on the artist Barry Le Va. A second book, currently in progress, will examine the intersection of experimental art and music in the 1960s. More recently, his research has lead to a larger interest in newer forms of “variable media,” including electronic and digital art. Maizels’s other academic interests include the histories of science and subjectivity, as well as the intersection of art criticism and art history. He is currently the Mellon New Media Curator/Lecturer at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College.

- Interview with Wilhelm Lipke. Reprinted on Robert Smithson estate website, from http://www.robertsmithson.com/essays/fragments. Also available in Jack Flam, ed. Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. ↩

- Bruno Latour. “Visualisation and Cognition: Drawing Things Together.” Knowledge and Society: Studies in the Sociology of Culture and Present 6 (1986): 1–40 ↩

- See Alex Ross, “Song of the Earth: The Arctic Sounds of John Luther Adams,” in Listen to This (London: MacMillan, 2010), 176–87. See also Daniel Crawford, A Song of Our Warming Planet (2013), video at http://ensia.com/videos/a-song-of-our-warming-planet, as of 10/14/14. ↩

- Adams was in fact deeply influenced by Feldman’s Piece for Four Pianos (1957). See John Luther Adams, Mixtapes: Music to Leave this World (WKCR Artist Profile Series, 2013), at http://www.wqxr.org/#!/story/music-leave-world-john-luther-adams, as of 10/14/14. ↩

- For more information, see web documentation related to the recent reinstallation of Cloud Music at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, http://www.si.edu/tbma/saam_cloudmusic, as of 10/14/14. ↩

- See also the David Bowen’s project Cloud Tweets, in which software scans images of clouds and then, in response, types the letters on the keyboard over which the clouds would have passed. The results are posted to Twitter. http://dwbowen.com/cloud_tweets.html, as of 10/14/14. ↩

- Ross, 176. ↩

- Alain Robbe-Grillet, For a New Novel, trans. Richard Howard (Evanston, Il.: Northwestern University Press, 1992), 71. See also Justin Schorr; “Problems of Criticism VII: To Save Painting,” Artforum 8, no. 4 (December, 1969); 60. ↩