From Art Journal 73, no. 3 (Fall 2014)

Unless otherwise indicated, translations from the Spanish are by the author.

The subtlest of deceptions lies in wait in a “1000 Words” feature on Roberto Jacoby in the March 2011 issue of Artforum.1 Among the article’s accompanying illustrations is a photograph of a seated, shirtless man dressed as a satyr, with horns and a fake beard. It is identified as documentation of one of the foundational conceptualist works in Argentina: Eduardo Costa, Raúl Escari, and Jacoby’s Happening para un jabalí difunto (Happening for a Dead Boar), 1966. Reports of a Happening that never actually happened were distributed to newspapers and magazines, with the artists revealing their hoax in the same publications two months later.2 If there was a Happening, it consisted of the mass reception of the news stories. The project inaugurated a new genre, arte de los medios de comunicación (media art), in which both art objects and events would no longer be necessary. Instead, works of art would subsist entirely within the mass media, existing as information circulated via newspapers, television, or other channels of communication.3 In his 2011 “1000 Words,” Jacoby connects this early project to his contemporary work, garnering valuable attention for both in a major international art magazine. The photograph in question, however, is incorrectly captioned. In the exhibition catalogue for Jacoby’s recent retrospective at the Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, a cropped version of the same image is identified as a detail of the 2010 “materialization” of the 1966 work—forty-four years after the original.4

This microfiction is buried in supplemental information, the accuracy of which is easily taken for granted. If the error was indeed planted by Jacoby when he supplied the magazine with publishable images, it is of a different nature than the hoax at the center of Happening para un jabalí difunto, which the artists made public. In this case, research is required to excavate the mistake. Once unveiled, however, it similarly calls attention to the magazine as a mediating factor—to Artforum’s operations as a tastemaker for global contemporary art. The magazine did not report on Jacoby’s 1960s experiments when he was producing them, but amid the recent surge of interest in postwar Latin American art, he has been (re)covered as a contemporary artist in close dialogue with his past work.5 It is precisely now, at this unique moment of visibility, that Jacoby plants a seed of doubt. What does it mean to have Artforum’s stamp of approval—can the magazine be relied on to get the record straight? Indeed, what would the “straight” record even look like? The caption, after all, is not merely erroneous; it instantiates a collapse of present onto past.

What follows is a consideration of Jacoby’s career that attends to his periodic manipulations of art-historical truth, which have ranged between highly visible and nearly imperceptible gestures. My contention is that from his earliest work through the present day, Jacoby has understood art history, with its organization of facts, dates, and credit, as fair game for intervention and alteration. At times (as in the example above) this has rendered his mass-media and institutional contexts more conspicuous, while questioning the claims of experiential or political authenticity that are frequently attached to Latin American art both past and present. Yet the stakes of this project do not only bear on the wider dissemination of his work today. Artists in Jacoby’s mid-1960s Buenos Aires milieu were preoccupied with their own history even as it unfolded, systematically problematizing authorship, assertion, and documentation. As his recent work has reflected on this era, Jacoby has made pointed references to the interdisciplinary cultural critic Oscar Masotta, a close colleague and mentor of the media-art group. Masotta, who played with minute disjunctions and fictions in the service of his unique approach to “apperception,” is at the center of an erotics of influence that Jacoby has gradually constructed over the last decade. Any contemporary consideration of Jacoby, and Argentine conceptualism more generally, would do well to take his alternative art history and its implications into account.

From Self-Promotion to Apperception

Jacoby’s emergence as an artist coincided with a larger crossroads for Argentina. The country had emerged from the 1950s under the spell of developmentalism, which brought rapid industrialization and the information age in short shrift. Funded by the Di Tella family’s manufacturing wealth, the Instituto Torcuato di Tella provided a centralized venue for the new experimental practices of the decade, supporting artists through prize competitions and group exhibitions that traveled to international venues.6 Amid this cultural efflorescence, the country was politically unstable. Led by the officers who had overthrown president Juan Domingo Perón in 1955 and banned his political party, the military closely monitored elected officials for signs of communist sympathies. Democracy was suspended in 1962 and dispensed with altogether in 1966, when a junta was installed that would remain in power into the early 1970s. Under General Juan Carlos Onganía, intellectuals and youth were particular targets, as when soldiers invaded the Universidad de Buenos Aires and beat up faculty and students who were occupying school buildings in the coup d’état’s immediate aftermath.7 The Di Tella remained a refuge for artistic experimentation, however, so long as political statements were coded rather than explicit.8

In the early years of the decade, Alberto Greco pioneered a self-promotional, expressionist brand of action art that later artists like Jacoby would strip of its shock and references to the body. Greco traveled extensively in Europe and learned of international trends such as Nouveau Réalisme. What Kaira Cabañas has called the “performative realism” of Yves Klein and others informed Greco’s works and publicity stunts.9 When he returned to Argentina in 1958 as an “informalist” and painted some of the country’s first monochromes, he apparently urinated on some of the canvases, as if territorially marking this imported convention.10 He made light of his geographical origin and artistic ambitions in a series of street posters reading “Alberto Greco: El pintor informalista más importante de América” (America’s Most Important Informalist Painter) and “Alberto Greco: ¡¡Qué grande sos!!” (How Great You Are!!), in 1961. The posters can be read as both serious authorial claims and jokes. By this time he had rejected informalism, rendering competition with any other such painters, American or otherwise, a lost cause. Greco’s marveling at his own “greatness” could certainly be taken as further self-mockery, if not for his subsequent Vivo-Dito works, 1962, in which various objects and people in public space were circled and signed by the artist. The Vivo-Ditos imply the possibility of nominating all the world’s people and things as his work, which obviously comes into conflict with similar gestures by other artists, past, present, or future, to do the same.11

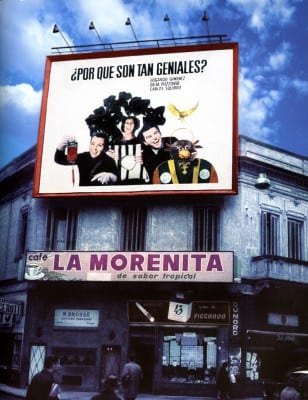

Greco died in 1965, the year that variations on Pop art began to appear in Buenos Aires. A new generation of artists closely supported by the Di Tella drew on Greco’s self-promotional stunts, as when Edgardo Giménez, Dalila Puzzovio, and Carlos Squirru appeared on a billboard on the corner of Avenida Viamonte and Calle Florida in Buenos Aires. Grinning beneath the tagline “¿Por qué son tan geniales?” (Why are they such geniuses?), the artists resembled actors in an advertisement (and the billboard was indeed coproduced by the Meca advertising agency).12 Giménez, Puzzovio, and Squirru preen alongside their own assemblage works of the period, the implication being that the artworks answer the question at hand. As with Greco’s “how great you are,” however, this is a genius borne by the question itself; they are “so brilliant” because the billboard asserts as much on the way to asking why. If this is a campy send-up of advertising, it nonetheless still functions as self-promotion.

Pop also inspired Masotta’s first writings on art. Already established as a literary critic for journals such as Contorno in the prior decade, Masotta discovered Jacques Lacan’s writings in the early 1960s.13 Shortly after, he declared himself a “structuralist” who aimed to introduce Argentine intellectuals to trends in international theory.14 First delivered in September 1965 and published in 1967, Masotta’s lectures on Pop art exemplify his creative approach to reporting on international culture, in this case the works of Andy Warhol, George Segal, and others. In the introduction to the book version of El “pop-art,” he confesses to not having seen the works he lectured on in person, but only through magazine and newspaper articles (some of the book’s illustrations still have captions visible from the original sources from which they were directly reproduced).15 This perhaps contributed to his sense that such works are not so much “about” their message—news events, celebrities, products—as the conditions that make mass communication possible, which he terms codigo, or “code.” For Masotta, Pop artists find ways to draw attention to code over message, breaking up the legibility of the popular image so that its code can be perceived and comprehended.16 Of Warhol’s repetitions, for example, he writes, “His multiplications do not pretend to express, but, I would say, to signify . . . that is that they want to make us feel the presence of the code. . . . In Warhol . . . intention opens onto a field of logical relations, that is to say: onto a code; or indeed that called a structure . . .”17 Masotta calls this process of becoming conscious of the code “apperception,” invoking a Kantian term: “The word refers always, in spite of differences in context, to the idea of a reflexive, highly intellective principle proper to certain mental operations. And it appears also in the psychology of art to designate a certain type of acts of consciousness that are distinguished from perception and imagination, and would realize themselves not so much through a lone act of consciousness but placed in relation to various successive valuated acts.”18 Masotta produced a uniquely creative reading of Pop distinct from that of other contexts outside the United States, where in many cases it was the artists’ political commitment that was up for debate.19 Instead, Masotta saw in Warhol and others a model for art, via apperceptive experience, to train the viewer to look and think critically. This belief informed Masotta’s interdisciplinary practice over the following two years, which included writings, artworks, and perhaps his most important contribution to Argentine art: a collaborative group of like-minded artists, Jacoby among them, that held weekly reading groups and would continue working long after Masotta’s interest in art waned. They would meet at Masotta’s apartment, particularly after he lost his position at the Universidad de Buenos Aires during the military coup.20

The dictatorship’s effects on the group’s experiments are marked by the appearance of deception as a strategy. Masotta first devised the Happening Para inducir al espíritu de la imagen (To Induce the Spirit of the Image) after returning from a trip to New York in April 1966. It was delayed until October because of the coup. One component of the Happening was based on a La Monte Young sound environment Masotta had experienced.21 A group of twenty people, all of whom were middle-aged and shabbily attired, was subjected to abrasive noises and lights for an hour. This was slightly altered from the version planned in April. The participants were originally to have been selected from what Masotta called the “the downtrodden proletariat”—shoeshine boys, beggars, and disabled people. The October version substituted lower-middle-class actors dressed to look poor.22 “Against the white wall,” Masotta writes, “their spirit shamed and flattened out by the white light, next to each other in a line, the old people were rigid, ready to let themselves be looked at for an hour.”23 With this slight discrepancy between actual economic class and dress-up, Masotta turned his participants into a suspect image, a sort of live version of the training in critical thinking that he had previously argued was North American Pop’s objective. The Happening staged an interpellation of one class by another—what he described as “social sadism.” The possibility remained, however, for viewers (or, more likely, the readers of Masotta’s account of the project) to become aware of their own instinct to “code” a given social group based on appearance. The Happening was being reframed in Buenos Aires as representation and fiction rather than presence and authenticity.

Dead Boars

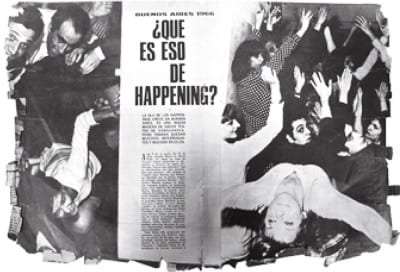

Happening para un jabalí difunto was a collaboration generated by Masotta’s reading groups, and the only project on which Eduardo Costa, Raúl Escari, and Jacoby would all collaborate.24 As Masotta would later attest, Jacoby first proposed the idea of a Happening that would consist only of its own documentation and dissemination in the mass media. Earlier that year, Jacoby had already devised artworks premised on absences—missed encounters with the real, as it were. >em>Maqueta de una obra (Maquette for a Work), 1966, for example, is a preparatory sculpture for a final work that is never produced, “finished” by being forever unfinished. Happening para un jabalí difunto, in contrast, played with the truth-claim of the photographic record. The artists first asked a group of minor celebrities to “invent their own participation in the supposed Happening,” and then had the artist Rubén Santantonín take photographs in various locations that were submitted as documentation: ambiguously chaotic images of youthful exuberance or decadence. They took care to note the circulation of each newspaper and magazine that they were deceiving, as if tracking the possible expanded audiences that the project could have. The deception, in this case, was framed as a kind of sociological experiment, one with a political undertone. Several of the publications the artists used, in particular Jacobo Timerman’s newsweekly Primera Plana, had predicted and applauded the dictatorship just two months earlier, accepting at face value the military’s claim that it was above politics and only concerned with keeping order.25

Happening para un jabalí difunto corresponds to the category of the “parafictional” that Carrie Lambert-Beatty identified in 2009 as “an important category in recent art.” She writes, “Post-simulacral, parafictional strategies are oriented less toward the disappearance of the real than toward the pragmatics of trust. Simply put, with various degrees of success, for various durations, and for various purposes, these fictions are experienced as fact.”26 Costa, Escari, and Jacoby’s experiment suggests that Lambert-Beatty’s category is by no means unique to contemporary art. In Buenos Aires in 1966, the parafiction served at least three objectives: to argue that action-based art, as inherited from Northern centers like New York and Paris, was ultimately an effect of its own reportage; to generate apperception of the mass media as a substrate for works of art; and to draw attention to the ease with which falsehoods could be (and had been) circulated via that substrate. Political protest is here synonymous with art and media critique.

Masotta’s 1967 lecture “Después del Pop: Nosotros desmaterializamos” (After Pop, We Dematerialize) served as a summary of media-art experiments between 1965 and 1967. It was written just prior to Lucy R. Lippard and John Chandler’s essay “The Dematerialization of Art,” in which they argued that artists were gradually reducing art to processes and information via “spareness and austerity.”27 Masotta’s desmaterialización shares this logic of reduction, but as a parallel of technological change and media obsolescence. The essay begins by quoting a 1926 text by El Lissitsky—who may have coined the term “dematerialization”—in which he anticipates the replacement of the book by the telephone and radio.28 Masotta discusses how a recent vogue for Happenings in Buenos Aires was in fact an effect of mass-media saturation reporting, which he terms sobreinformación, or “over-information,” rather than reality. This charted the path for a new approach, one that would supersede the Happening or make it outmoded. Effectively hunted down and killed, the “dead boar” of the Happening could be discarded, leaving the mass media as the future conduit of art. “I can affirm,” Masotta writes, “that there was something within the Happening that allowed us to glimpse the possibility of its own negation, and for that reason the avant-garde is built today on a new type—a new genre—of work.”29 In light of Masotta’s invocation of the avant-garde, it makes sense that Happening para un jabalí difunto was at other times referred to as Anti-Happening. Although Masotta had found fruitful tools in Pop, he glimpsed in the Happening a way to escape from dependence on Northern style.

Not all media art was premised on deception. Jacoby’s open- and closed-circuit projects of 1967 are straightforward reflections on how communication technologies function. In this case, an unrealized proposal for Experiments in Art and Technology, made during a trip to New York with Masotta, sets up a relay between television and teletype machines that report only on each another’s transmission of information.30 On the other hand, in the same period, there are indications of Jacoby’s increasing interest in the social upheaval of the era and its communicational tendencies. At a hippie gathering in Central Park, he wore photographs of Mao Zedong and of Perón, who was at that time in exile and believed by the Argentine Left to be a hero who, if he returned, would lead a socialist revolution. Drawn from an actual student chant of the era, Jacoby’s title for this action, Mao y Perón, un solo corazón (Mao and Perón, a single heart), joins the two historical figures through rhyme rather than proof of ideological affinity.31 Pinned to Jacoby’s chest, the two portraits imply mobility, as if they were exchangeable for others. Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s assassination later that year was marked by a commemorative exhibition in Buenos Aires. Jacoby’s contribution, a poster with a the iconic Korda photograph of Che set against a red background and white text that reads Un guerrillero no muere para que se lo cuelgue en la pared (A Guerrilla Does Not Die Just to Hang on the Wall), 1968, sets up a paradox that recalls his Maqueta, pointing out the literal limits of the work of art in the face of political mobilization. The guerrilla does not die just to hang on the wall, but the inspirational poster that delivers the message does have to hang somewhere; it needs some sort of support or exhibition context.

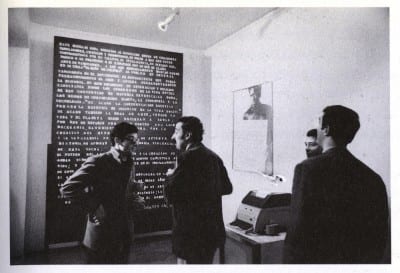

A certain ambivalence can still be detected in Jacoby’s participation in Experiencias ’68 at the Di Tella, the turning point of the entire era of Argentine art. When one artist’s work was censored for garnering antidictatorship graffiti, the rest of the exhibiting artists dismantled their works and left them in the street outside the Institute, forever severing ties. Jacoby’s Mensaje en el Di Tella captured the heightened tensions of the era. It consisted of three elements: a text by Jacoby that was reproduced in large print in the gallery, a photograph of an African-American protester at an antiwar rally in the United States, and a teletype machine feeding real-time information about May 1968, then unfolding in France. The text was displayed using white detachable letters on a large blackboard, with a handwritten signature at the bottom. “The future of art,” it reads, “is not connected to the creation of works, but to the definition of new concepts of life, with the artist as propagandist for these concepts.”32

There was not just one “message” in this work, but at least three: Jacoby’s call to dissolve art into life, the text on the protester’s sign, and the streaming information of France-Presse. Each message relied on a different medium: Jacoby’s prefabricated letters on the blackboard, the journalistic photograph of the protester, and the telex for the news. The artist made his aims clear in a shorter message, placed next to the telex machine: “I want to point out that the content [of the three messages]—especially that which is explicitly ideological or social—possesses a material reality in the consciousness of the receivers.”33 This logic echoes Masotta’s apperception, in which messages are fragmented, emptied, or falsified for the sake of such “consciousness” of code or media. Rather than voiding his messages outright, however, Jacoby played a balancing act. His passionate argument for moving beyond “aesthetic contemplation” was written with interchangeable letters, as if hinting that it was only one of other possible sentiments. As much as the telex brought news of revolutionary change into the gallery setting, it also arrived as information spit out mindlessly by a machine. The photograph of the black protester, like the open-ended signifiers of youth and creativity in the Happening para un jabalí difunto photographs, has an ambiguous interpretation depending on the viewer’s ideological perspective (one need only think of the polarizing effect of Muhammad Ali, who had refused to be drafted into the US Army one year earlier); simultaneously emblem of the international proletariat and target of those in power. Mensaje en el Di Tella is poised between analysis of propaganda and the uncritical use of propaganda.34 Jacoby oscillates between political commitment and voided messages that make conspicuous the media conditioning and delivering them. Mensaje en el Di Tella additionally poses the question of art history’s relationship to history proper: “The avant-garde is the intellectual movement that permanently repudiates art and permanently affirms history.”35 Like Masotta before him, Jacoby draws on a history of the avant-garde that dictates art’s future. This self-conscious turn in art history and the “history” being photographed and reported over the wires here share common ground not in life or action itself, but in their materialization as messages.

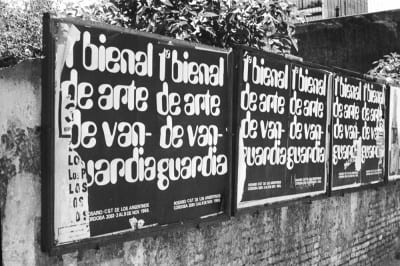

In August 1968 Jacoby was integral in the group discussions that led to the November opening in Rosario of the exhibition Tucumán Arde (Tucumán Is Burning). A protest environment installed in a union headquarters, Tucumán Arde bombarded those who entered it with overwhelming textual, photographic, and audiovisual evidence of the dictatorship’s economic crimes in the northwestern province of Tucumán. The organizers, who included journalists and union activists as well as artists, described the environment as a circuito sobreinformacional, using the same term Masotta used a year earlier to describe the media’s obsession with Happenings.36 In this case, sobreinformación was framed positively: the overload of information was to reiterate the message to the point of incontrovertibility. The project used a media-art-style deception, too, publicizing a fake “biennial of avant-garde art” to provide cover for the environment. Rather than imparting apperception for its own sake, however, this strategy was now ostensibly in the service of a larger ideological end; propaganda appeared to have won out. Yet given Jacoby’s connection to media art, it is interesting to consider alternate readings of, for example, the photography that was employed in Tucumán Arde to document rural poverty. Could even Tucumán Arde, in its own right, have contained some reflection on its own truth-effects—on the photography of proletarian subjects taken back to a city to inspire an educated public? The majority of the artists associated with this project subsequently took long hiatuses from making art, some permanently. Jacoby’s lasted roughly twenty years, during which time he trained and worked as a sociologist at the Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Viruses

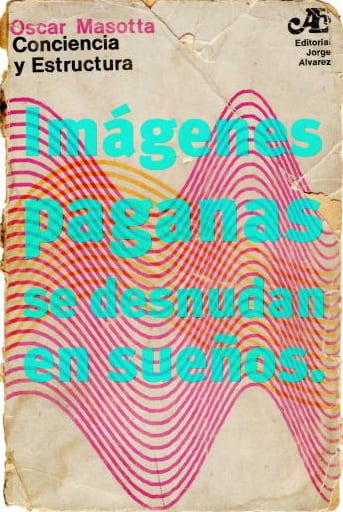

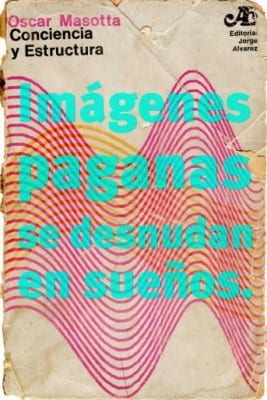

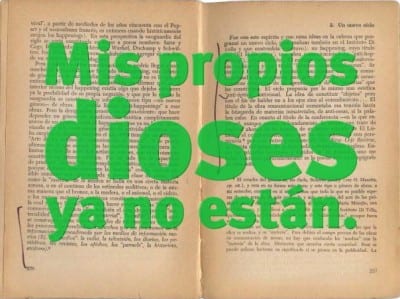

Jacoby’s 1968: El culo te abrocho (1968: I Do Your Ass), was first shown in 2008, at the short-lived Galería Appetit in Buenos Aires. It is a series of thirty digital prints of objects from the artist’s personal archive, among them photographs, typed notes for works, newspaper and magazine clippings, leftist cartoons, and pages of books. Dating between 1966 and 1970, the archival images are overlaid, via photo-print, with brightly colored texts consisting of quotations and excerpts from Jacoby’s later writings from the 1970s through the present. The combinations of text and document superimpose more recent quotations onto the material surface of the late-1960s archive. Jacoby includes two images of the same book, Masotta’s Conciencia y Estructura (Consciousness and Structure), in which Masotta’s lecture “Después del Pop: Nosotros desmaterializamos” was first published.37 This is a curious inclusion, given that Conciencia y Estructura is not a precious or rare archival document—it was a widely published text. One image is of the cover, while the other shows pages 226 and 227, where Masotta identifies media art as a specifically Argentine mode of dematerialization.

The texts surprinted on these two images are lyrics from the song “Imágenes Paganas,” by the pop group Virus, for which Jacoby wrote songs in the late 1970s and 1980s. With a homosexual lead singer and bold performance aesthetic, Virus was a rebuke to the military junta that had taken power in 1976. At a moment of profound national despair and at the risk of its members’ own lives, Virus embodied what Jacoby would later call “la estratégia de la alegría,” or “the strategy of joy,” championing disco-era hedonism and sexual liberation as a radical alternatives to authoritarian control. “The ‘strategy of joy,’” Jacoby reflected in 2000, “manifested in musical styles, in forms of presentation, in stage sets, clothes, and makeup: free movement, games with identity, ludic transformation of the environment. Bodies rediscovered the possibilities of entering or creating fictional spaces, visiting alternate, imaginary realities where the crystalline world of solitary and obligatory behavior kept eroding.”38 This was concurrent with the Proceso de Reorganización Nacional, the campaign of torture and disappearances—possibly as many as thirty thousand—carried out by the regime. “Joy,” in a time of crisis, sounds like a fiction, but of a utopian variety: a radical disavowal of present conditions.39 1968: El culo te abrocho figuratively maps Jacoby’s activity during a period in which he was not a practicing artist onto his 1960s archive—albeit, in this case, onto a book written by someone else. Juli Carson, who exhibited 1968: El culo te abrocho in the United States, reads this in Lacanian terms, arguing that Jacoby operates on the “primal scenes” of conceptualism to preserve the possibility of a contemporary “critical aesthetics.”40

Although from the same song, the lyrics printed over the two images of Conciencia y Estructura are distinct. Over the cover of Masotta’s book, one reads “Imágenes paganas se desnudan en sueños” (Pagan images disrobe in dreams), while the text superimposed on pages 226 and 227 laments, “Mis propios dioses ya no están” (My own gods are no longer). The former conveys erotic desire, the latter a sense of loss that might be associated with Masotta, who died in 1979 (the original song adds, “espejismos,” or mirages). But if Masotta was indeed a “god,” he has been profaned. Jacoby alters, even violates, this trace of his colleague’s work, as he does with so many images from his own archive. The title of the series adapts an Argentine expression of contempt for anything that rhymes with “abrocho”(abrochar means “to sew up” or “to fasten”). The archive “1968” is figured as a body with a rectum that can be fastened, sealed off. In this interpretation, the artist is sewing up the productive capacity of the archive, perhaps in an effort to halt the historical conversation it generates. The rhyming words of the title, “Sesenta y ocho, el culo te abrocho” momentarily empty the entity “1968” of its meaning, instantiating the loss of the date’s spectral power and the inauguration of new, expressly contemporary functions for the archive.41 Abrochar can also mean to “to struggle” or “to wrestle” with something, and in its popular slang use—one always implied in the children’s rhyme from which the title derives—to “take” or to “fuck” someone else.42

This bodily logic was anticipated in La castidad, a 2007 collaboration in which Jacoby and Syd Krochmalny, a young art student, entered into a widely publicized “platonic relationship,” complete with the production of platonic dialogues. Given that some of the texts were published in a porn magazine, the project attracted skepticism from all quarters—the general assumption was that the commitment not to have sex was a fiction. One section of the dialogues reads:

Syd: Tell me about bodies, about all the bodies that attract and confuse you, asphyxiate and invade you. Of the bodies that we are and through which we endure indecent dreams . . . of the bodies in which we wake up, howling with terror.

Roberto: This will take us a ways, are you up for it?

Syd: Walk, I long for your words.

Roberto: We have already begun. Perhaps you didn’t hear me?

Syd: Sure, but perhaps we’re not speaking? I am giving you my full attention.

Roberto: So my voice has penetrated you. Something from my body—the fine grain of my voice flew up to the window of your ears and entered into you without opening your gates to me.43

A similar erotics is in play in 1968: El culo te abrocho. A “voice”—this time a written text—“invades” and infects each archival artifact. If the historical object originally had influences or collaborators, these authorial subjects are confused, intertwined.

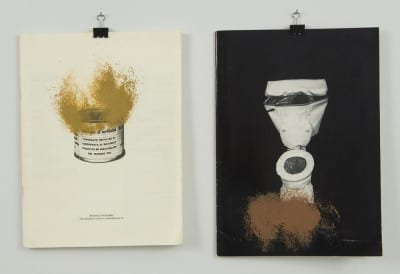

The series also shares affinities with 77 Testicular Imprints, an artist’s book and series of works on paper by Nicolás Guagnini that Jacoby saw in New York in 2007. Dipping his testicles in bright paint and applying them to collectors’ items such as first editions of philosophy books, vintage magazines, rare posters, and ephemera, Guagnini contaminated the archival purity of his objects through indexical traces of his own body. In his introduction to the “1000 Words” text of 2011, Guagnini remembers that when he was a child in Buenos Aires, Jacoby played a game with him in which they cut the captions out of comic strips to switch the identities of the heroes and the villains to “make the bad guys win.”44 A child’s version of Jacoby’s critique of political rhetoric in the late 1960s, this trick meant something altogether different in 1976. Guagnini’s father had been “disappeared” by the dictatorship, and Jacoby was acting as a substitute, providing guidance, while poetically accounting for a world in which the bad guys were indeed winning.

In 1968: El culo te abrocho, the chief object of archival anxiety has become the artist’s own past self as represented by archival relics, while the material record of the artist’s erogenous zone has been exchanged for the quotation: language that, even if originally produced by one author, can be excerpted and recontextualized (many of the texts are Jacoby’s quotations of other authors). In the two images based on Conciencia y Estructura, it is as though Jacoby blurs the boundaries between his past and present selves with that of Masotta, himself no stranger to the vagaries of authorship. In his 1965 essay “Roberto Arlt, yo mismo,” Masotta wrote about his own recent discovery of Lacanian psychoanalysis instead of about Arlt, the fiction writer who was his ostensible subject.45 A closer inspection of Jacoby’s photo-printed image of pages 226 and 227 reveals that the Masotta text is not identical to the original edition of 1969. Jacoby has turned endnote 7, which credits him alone with the invention of media art, into a footnote, so that it appears on the same page. The material veracity of the archive has been tampered with in the service of a certain truth, one that aims to sew up forever any debates about credit. In the process, Jacoby has leveraged a different truth: the collaborative nature of almost all the initial salvos of Argentine conceptualism.

Zombies

In the aforementioned “1000 Words,” Jacoby addresses his censored project for the 2010 Bienal de São Paulo, El alma nunca piensa sin imagen (The Soul Never Thinks without an Image). A collaborative endeavor, the project was cut short because of its apparent support for Dilma Rousseff’s presidential candidacy, which was in direct violation of the event’s regulations (it is literally a crime in Brazil to use government-appointed funds in favor of any specific political party). The Brigada Argentina por Dilma, the group of intellectuals who accompanied Jacoby to São Paulo and who could not vote in the election, held a series of “ludic pedagogical workshops” within the exhibition space until the project was shut down. The Bienal’s theme was, ironically enough, that art and politics could not be separated, a familiar refrain among the many recent biennials that have added to the reputation of Latin American conceptualism as authentic, participatory, and political, “thriving on adversity,” in Hélio Oiticica’s famous words.46 Regardless, the curators released a statement insisting that they had had no idea what Jacoby had planned to do. “The artist,” they wrote, “asserted that he intended to use a fictitious and hypothetical campaign as a platform for reflection upon electoral processes in general. . . . On the opening night of the 29th São Paulo Biennial (September 21), contrary to the assurances made to the curators, Mr. Roberto Jacoby and the rest of his ‘Argentinean Brigade for Dilma’ not only distributed campaign pamphlets in favor of Dilma Rousseff, but ran video footage featuring declarations of support for the candidate.”47 The video in question includes a series of poorly produced “testimonials” from various artists and intellectuals in Buenos Aires, some of whom pledge their support for Rousseff half-heartedly, as if they are not quite sure to whom they are referring. The ambiguously optimistic images and rhetoric in the video recall Happening para un jabalí difunto. Jacoby appears at one point with a beneficent smile, addressing the viewer in “Portuñol,” a combination of Spanish and Portuguese—something of a fictional language. He claims to be the representative of a “new Argentine cult, the movement of the Devil,” and speaks of Rousseff with idealistic praise.

“Was this a real electoral campaign,” says Jacoby in Artforum, “or an artistic fiction? Isn’t the art institution the space that confers the status of ‘the ideal’ on any image or process that develops within it?”48 He claims that El alma nunca piensa sin imagen was “not very different” from Tucumán Arde, likening the icon of Latin American political conceptualism to a cleverly engineered scandal—yet perhaps he was not merely being irreverent. This reflection could be understood as locating Masotta’s apperception in Tucumán Arde’s surfeit of propaganda, so that even the latter becomes a reflection on activist art and its media, despite its sincere activism. El alma nunca piensa sin imagen, in turn, critiques how a new canon of political art in Latin America is being used to build an art market and an internationally powerful set of institutions in the region today.49 It also served as an effective way to distinguish Jacoby from surviving rosarino colleagues from Tucumán Arde, who have continued to historicize and promote the project as a traveling archive that has been installed in various biennials and gallery exhibitions. This is not to say that Jacoby is no longer interested in politics, however. One of his most recent works, 14Bis Panfleto de la Extrema Democracia (Pamplet of Extreme Democracy), 2011, involved the obsessive reproduction of a little-considered passage in the Argentine constitution that protects dignified working conditions, access to adequate housing, and other social rights—in this case, a utopian fiction, rendered into law, that remains in potential as reality.

At a roundtable on Argentine contemporary art at the Americas Society in New York in 2007, Jacoby declared the 1960s version of himself “dead.” He wanted to stop having to answer for his earlier self’s actions, he explained, asserting that he is now a contemporary artist like any other, focused exclusively on the concerns of the present.50 Certainly, in the last twenty years, in addition to his own artistic production, Jacoby has been one of the most influential figures in Buenos Aires art, using his own funds to support contemporary art spaces that have shaped successive generations of new artists. In the process, these artists have formed substantial international networks, becoming “amigos de Jacoby,” to quote the phrase that circulated in one such initiative, Tecnologías de Amistad (Technologies of Friendship), 2006, and through alternative spaces such as Belleza y Felicidad, run by Fernanda Laguna in Buenos Aires from 1999 to 2007.51 His most recent institutional project is the Centro de Investigaciones Artísticas, or C.I.A., in Buenos Aires, 2009–present, for which all collaborators and participants are given the title of agente, or agent.52 This contemporary activity, however, is unimaginable without Jacoby’s identity as a now-canonical 1960s artist—an association that he reconfigured and revitalized in 1968: El culo te abrocho. If the 1960s Jacoby is dead, this corpse still engages in zombie aesthetics, feasting on living and defunct alike.

Daniel R. Quiles is an assistant professor of art history, theory, and criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he teaches courses on the theory and history of postwar art of the Americas. He is currently writing a book manuscript titled “Ghost Messages: Oscar Masotta and Argentine Conceptualism.”

This essay originally appeared in the Fall 2014 issue of Art Journal.

- Nicolás Guagnini, “1000 Words: Roberto Jacoby Talks about El alma nunca piensa sin imagen (The Soul Never Thinks without an Image), 2010,” Artforum International 49, no. 7 (March 2011): 248–50. ↩

- Eduardo Costa and Roberto Jacoby, “Realización de la primera obra,” in Happenings, ed. Oscar Masotta (Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Álvarez, 1967), 113–18. ↩

- Eduardo Costa, Raúl Escari, and Roberto Jacoby, “Un arte de los medios de comunicación (manifiesto),” in Happenings, 119–22. ↩

- The exhibition took place at the Reina Sofía between February 25 and May 30, 2011. See Roberto Jacoby, El deseo nace del derrumbe: Roberto Jacoby; Acciones, conceptos, escritos, exh. cat., ed. Ana Longoni (Barcelona: Ediciones de La Central/Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2011). A blog posting with color photographs of the 2010 event identifies the satyr as “Sátiro Gabínides,” here, as of November 24, 2014. The artist identified him as Horacio Gabin, a clown and performer, in an e-mail of December 1, 2014. ↩

- The present wave of interest in Latin American modern and contemporary art arguably began with Héctor Olea and Mari Carmen Ramírez’s 2000 exhibition Heterotopías: Medio siglo sin-lugar 1918–1968 (Heterotopias: A Half-Century without Place) at Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid (restaged as Inverted Utopias when it traveled to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 2004), which represented a major departure from a previous, essentialist canon that privileged the “fantastic.” Olea and Ramírez instead focused on expressionism, abstraction, and participation, calling particular attention to the media and political emphases of the region’s conceptualism. See Heterotopias: medio siglo sin-lugar, 1918–1968, exh. cat., ed. Ramírez and Olea (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2000). ↩

- See Andrea Giunta, Vanguardia, internacionalismo y política: Arte argentino en los años sesenta (Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2001), later published as Avant-Garde, Internationalism, and Politics: Argentine Art in the Sixties, trans. Peter Kahn (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007). ↩

- Among other sources, see Liliana de Riz, Historia argentina: La política en suspenso 1966 / 1976 (Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2000), 42–58; and David Rock, Argentina 1516–1987: From Spanish Colonization to Alfonsín (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 333–58. ↩

- For an exhaustive history of political content in 1960s Argentine art, see Ana Longoni and Mariano Mestman, Del Di Tella a “Tucumán Arde”: Vanguardia artística y política en el ’68 argentino (Buenos Aires: Ediciones El Cielo por Asalto, 2000). ↩

- Kaira Cabañas, “Yves Klein’s Performative Realism,” Grey Room 31 (Spring 2008): 6–31. ↩

- Such reports about Greco’s methods were exhaustively chronicled for his retrospective in Spain. A specific claim that Greco urinated on his canvases was made by Luis Felipe Noé for a tribute exhibition in 1970. See Noé, “Alberto Greco: A cinco años de su muerte,” in Alberto Greco, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Galería Carmen Waugh, 1970); and Alberto Greco, exh. cat., ed. Francisco Rivas (Valencia: Fundación Cultural Mapfre Vida, 1991). ↩

- The title Vivo-Dito combines the Spanish word for “living” and the Italian word for “finger.” Greco’s strategy parallels that of many other artists at this moment, including Klein (selling air), Piero Manzoni (signing live models’ bodies), and, in Czechoslovakia, Stano Filko and Alex Mlynárčik, who declared all of Bratislava an artwork in their Happsoc I, 1965. Taking up Peter Bürger’s pejorative moniker “neo-avant-garde,” Benjamin H. D. Buchloh has argued that such gestures accompanied knowing repetitions of prewar avant-garde strategies. Buchloh did not address the possibility that such repetitions, when exaggerated, create a space for critique by artists from peripheral centers. Buchloh, “The Primary Colors for the Second Time: A Paradigm Repetition of the Neo-Avant-Garde,” October 37 (Summer 1986): 41–52. ↩

- See Rodrigo Alonso and Paulo Herkenhoff, eds., Arte de contradicciones: Pop, realismos y política Brasil-Argentina 1960, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Fundación Proa, 2011), 164–75; and Edgardo Giménez, ed., Jorge Romero Brest: La cultura como provocación (Buenos Aires: Edición Edgardo Giménez, 2006), 300–1. ↩

- For an overview of ,em>Contorno, see Oscar Terán, Nuestras años sesentas: La formación de la nueva izquierda intelectual en la Argentina 1956–1966 (Buenos Aires: Puntosur, 1991). ↩

- Oscar Masotta, “Roberto Arlt, yo mismo,” in Conciencia y Estructura (Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Álvarez, 1968), 177–92. ↩

- For example, see the illustration of Andy Warhol’s Green Coca-Cola Bottles, 1962–1963, Oscar Masotta, El “pop-art” (Buenos Aires: Columba, 1967), 87. ↩

- My forthcoming book manuscript, “Ghost Messages: Oscar Masotta and Argentine Conceptualism,” will trace this strategy of deliberate miscommunication throughout the work of Masotta, his colleagues, and subsequent Argentine conceptualists from the mid-1960s through the early 1970s. ↩

- Masotta, El “pop-art,” 65, emphasis in the orig. ↩

- Ibid., 73–74. “Apperception” as a philosophical and pedagogical concept goes back at least as far as Immanuel Kant, who differentiated between “empirical” (corresponding to changing states in the present) and “transcendental” (corresponding to experience as an a priori category) modes of apperception. Read through Masotta’s interest in Lacan, Kant’s “self-consciousness” would need to pass through the linguistic structures that constitute the decentered self. Hence the use of the term “apperception”: self-knowledge here is manifested through recognition of the codes that structure the surrounding, subject-constituting linguistic field. ↩

- Several recent exhibitions, including the upcoming International Pop at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (April–September 2015), have begun the work of comparing receptions of Pop in different global contexts. See also Alonso and Herkenhoff, Arte de contradicciones. ↩

- See Juan Andrade, Oscar Masotta: Una leyenda en el cruce de los saberes (Buenos Aires: Capital Intelectual, 2009), 115–32. ↩

- Happenings, 162–67. ↩

- Ibid., 199. ↩

- Ibid., 200, emphasis in orig. Spanish text. This can be likened to Masotta’s take in El “pop-art” on George Segal, whose cast-based sculptures he describes as “masks in reverse” that empty out the individuality of sitters into conventional gestures. In the conclusion of the book Masotta extends the argument to Pop as a whole, arguing that it is a response to the deindividualizing effects of North American capitalism. Masotta, El “pop-art,” 102–12. ↩

- Costa and Jacoby worked together on other projects, including Primera audición de obras creadas con lenguaje oral (First Recital of Oral Language Works), 1966, with Juan Risuleo, which featured tape recordings of everyday spoken language presented as “literary works.” See Jacoby, El deseo nace del derrumbe, 57–59. ↩

- This was invariably the position of the right-wing secret societies in the military that periodically organized coups in Argentina throughout the postwar period. See David Rock, Authoritarian Argentina: The Nationalist Movement, Its History, and Its Impact (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993). ↩

- Carrie Lambert-Beatty, “Make-Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility,” October 129 (Summer 2009): 54. ↩

- Lucy R. Lippard and John Chandler, “The Dematerialization of Art” (1968), rep. Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 46–50. ↩

- El Lissitzky, “The Future of the Book” (1926), rep. New Left Review 1, no. 41 (January–February 1967): 39–44. Masotta quoted Lissitzky in “Después del Pop: Nosotros desmaterializamos” (1967), in Conciencia y Estructura (Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Álvarez, 1968), 218–44; rep. as Oscar Masotta, “After Pop, We Dematerialize,” trans. Eileen Brockbank, in Listen, Here, Now! Argentine Art of the 1960s: Writings of the Avant-Garde, ed. Inés Katzenstein (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2004), 208–16. ↩

- Masotta, “After Pop, We Dematerialize,” 213. ↩

- Jacoby, ,em>El deseo nace del derrumbe, 78–79. ↩

- Perón’s return to Argentina in 1973 was marked by conflict and increasing repression of the far-left radicals who had supported him in absentia. When he died in 1974, his wife Isabelita organized the Alianza Anticomunista Argentina, a military death squad, to target the Montoneros and other revolutionary guerrillas. ↩

- Roberto Jacoby, “Message in the Di Tella” (1968), trans. Marguerite Feitlowitz, Listen, Here, Now!, 290. See also Jacoby, Media Art / Arte de los medios 1966–68, CD-ROM published by Jacoby, section on Mensaje en el Di Tella. ↩

- Jacoby, El deseo nace del derrumbe, 117. ↩

- As Longoni and Mestman report, this faith in aesthetics would be a source of conflict throughout the Tucumán Arde collaboration of 1968 that I discuss in the next paragraph, and a reason for the departure from the project of artists such as Margarita Paksa and Ricardo Carreira. The participating Buenos Aires artists were generally more disposed to retain elements of aesthetic reflection in the project, while artists from Rosario favored a more direct, propagandistic approach. See Longoni and Mestman, Del Di Tella a “Tucumán Arde,” 150–69. ↩

- Jacoby, “Message in the Di Tella,” 288. ↩

- See María Teresa Gramuglio and Nicolás Rosa, “Declaración de la muestra de Rosario,” in Del Di Tella a “Tucumán Arde,” 233–35. ↩

- Oscar Masotta, Conciencia y Estructura (Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Alvarez, 1968). Jacoby has championed this text as predating Lucy Lippard’s “The Dematerialization of Art” by a year. See Roberto Jacoby, “Después del todo, nosotros desmaterializamos,” Ramona 8–9 (December 2000–March 2001): 34–35. ↩

- Jacoby, “La alegría como estrategia” (2000), rep. El deseo nace del derrumbe, 411. ↩

- Jacoby incorporated a similar strategy more than a decade later, when the AIDS crisis struck Buenos Aires. A T-shirt campaign that drew on Jacoby’s work in advertising, Yo tengo SIDA (I Have AIDS), 1994, is another play on a doubtful claim. In this case, Jacoby devised a simple gesture that produced commonality between infected and healthy during the worst years of the epidemic. ↩

- Juli Carson, “Roberto Jacoby’s 1968: El culo te abrocho,” exh. brochure (Los Angeles: University Art Gallery, University of California, Irvine, 2009), n.p., at http://uag.arts.uci.edu/sites/default/files/RobertoJacoby_0.pdf, as of November 24, 2014. ↩

- It is important to point out that in its colloquial form, the phrase is expressly childish and nonsensical—an excuse to utter the word culo, with equivalents for other numbers such as “nueve, el culo te llueve” (nine, your ass rains) and “diez, el culo al revés” (ten, upside-down ass). ↩

- As Carson writes, “desire itself is at once the archive’s secret that dare not speak its name and its driving force.” Carson, “Roberto Jacoby’s 1968.” ↩

- Roberto Jacoby and Syd Krochmalny, “La Castidad” (2007), rep. El deseo nace del derrumbe, 445–49. ↩

- Guagnini, 248. ↩

- Masotta, “Roberto Arlt, yo mismo” (1965), 177–92. ↩

- See, among many other examples, Frederico Morais, ed., I Bienal de Artes Visuais do Mercosul, exh. cat. (Porto Alegre, Brazil: Fundação Bienal de Artes Visuais do Mercosul, 1997); Roger M. Buergel, ed., Documenta 12, exh. cat. (Cologne: Taschen, 2007); and Eungie Joo, ed., The Ungovernables: 2012 New Museum Triennial, exh. cat. (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2012). ↩

- See Moacir dos Anjos and Agnaldo Farias, “São Paulo Is Burning: A Response,” Chtodelat News, at http://chtodelat.wordpress.com/2010/10/13/sao-paulo-is-burning-a-response/, as of June 14, 2014. The curators are responding to an initial protest at the censorship by Jacoby. See also Brigada Argentina por Dilma, “Arde San Pablo: El fantasma de la política en la Bienal,” September 23, 2010, in Spanish and English at www.ramona.org.ar/node/34050, as of November 12, 2014. ↩

- Jacoby quoted in Guagnini, 250. ↩

- These range from market-driven initiatives such as the PINTA Art Fair, which took place in New York for several years and presently has versions in both Miami and London (see www.pintalondon.com/ and http://pintamiami.com/, as of November 11, 2014), to the radical archive research of the Red Conceptualismos del Sur (which, not insignificantly, helped to organize and sponsor Jacoby’s retrospective at the Reina Sofía; see Southern Conceptualisms Network, “Micropolitics of the Archive,” Asia Art Archive Field Notes 2 (December 2012), at www.aaa.org.hk/FieldNotes/Details/1208, as of November 25, 2014, and Ana Longoni et al., “Forum: Red Conceptualismos del Sur/Southern Conceptualisms Network,” Art Journal 73, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 14–115. ↩

- The panel included the curator Victoria Noorthoorn and the artists Marta Minujín, Judy Wertheim, and Marina de Caro, and I was the moderator. It was organized in conjunction with the exhibition Beginning with a Bang! From Confrontation to Intimacy: An Exhibition of Argentine Contemporary Artists, 1967–2000, which took place at the Americas Society, New York, in 2007. ↩

- See Syd Krochmalny, “Tecnologías de la amistad: Las formas sociales de producción, gestión y circulación artística en base a la Amistad,” ramona, at www.teoriasdelaamistad.com.ar/pagina5/Unidad10/Tecnologiasdelaamistad.pdf, as of November 12, 2014. ↩

- See http://ciacentro.org.ar/, as of November 12, 2014. For full disclosure: I gave a series of four seminars at Centro de Investigaciones Artísticas in the summer of 2013, on the theme of fiction in postwar and contemporary art. ↩