For several years, Los Angeles-based artist Math Bass has been building a body of crisp, highly stylized paintings that read like chapters of a book written in a strange font. The paintings—matte gouache on raw canvas—present an assortment of recognizable objects (flowers, cigarettes with plumes of smoke) and simple geometric shapes (circles, zigzags), but the familiarity of these forms is offset by the ambiguity of their relations. They butt up against one another, overlap, twist, and repeat in a way that is anything but linear. Bass’s videos and performances are equally slippery and multilayered, involving herself and others armed with a selection of everyday-looking props (a stick, a tarp, a potted plant), engaging in a series of routine bodily movements. Together, Bass’s works are a lively response to the cultural demand for immediate intelligibility. In the following conversation, Bass and I discuss the impetus behind her approach to “slowing time,” and the value of ambivalence.

– Mia Locks

Mia Locks: The first work of yours I saw was a video called Pass the Line (2011). In it, we see a few distinct cloaked forms—bodies beneath three different striped tarps or tents. They perform a series of movements in relation to a strange audio track that is absent of voices, featuring only musical and ambient sounds.

Math Bass: I used to make a lot of videos. Before that, prior to graduate school, I had a background in live performance. In a way, Pass the Line and other videos from that time were a shift away from the emphasis on my presence and my body as a performer.

Locks: So the body gets hidden beneath a brightly colored, circus-like tent? That’s interesting—a desire to shift away from the body that actually draws attention to its concealment. Like when small children first learn to play hide-and-seek, and they “hide” in the most obvious ways [laughter]. Do you think about withholding or concealing your own body as a kind of a resistance to the ways in which readings of one’s work can get so easily mapped onto one’s personal biography?

Bass: To be honest, it was a sincere attempt to cope with the anxiety and nervousness I was experiencing as a performer. Everyone who performs live has to grapple with that anxiety. You have to bring that ecstatic nervous energy in order to be fully present. For me, it went from being generative and exciting to making me feel depleted. I didn’t want to do it anymore. Now I’ll perform collectively, but it is still really intense for me.

Locks: Can you tell me more about those earlier solo performances? What did they entail?

Bass: There was always some kind of a sound element that was central to the performance. In Another Country (2010), I had my scooter, a wireless microphone hooked up to me, two speakers, and I was wearing my helmet. My voice was both live and projected through the two speakers, located at the other end of the room. A triangular formation was created between me and the pair of speakers, formed by my voice and the two other sound sources. I also held two speakers on the scooter that played a prerecorded vocal track. I was singing this song that I wrote: “I am going to kill you and you are going to make me feel like I am from another country.” Meanwhile, my scooter was running and I was filling the room with carbon monoxide.

Locks: That sounds intense. Where was that?

Bass: In Los Angeles. It was at Human Resources in Chinatown, in their old space before they moved to the bigger space where they are located now. It was part of a performance festival called Perform! Now! Chinatown in 2010.

Locks: This idea that “you are going to make me feel like I am from another country” situates the viewer in a kind of awkward position. It implicates us. It asks us to consider the ways in which looking can be alienating, or can cause others to feel alienated. I’m curious to hear more about other early performances.

Bass: My very first solo performance was called Chickens’ Feed (2004). For that one, I was wearing a cloak, and it took place on a stage where I laid down a bunch of newspaper. There was also a tall ladder on the stage. I brought out two chickens and put them on the ladder, and then I climbed up the ladder with a bucket. When I got to the top, I let the cloak drop and I was naked. I took two handfuls of the food and threw it down at the chickens while I screamed, “chickens, feed!”

Locks: Wait, live chickens?

Bass: Yeah. Those early solo performances were all pretty short. Short but packed! Also funny and playful.

Locks: There’s something about the tone of those performances that seems to resonate in your recent work. There is a desire for playfulness. It’s quick or light, but there is a double register. There’s a seriousness about it, too. It’s not just play for the sake of fun, or a theater of the absurd. I think it has to do with something you once described to me, about holding an image or a form for a moment and it being fleeting, unfixed. That is a kind of parallel to the process of identification (or disidentification) and how identification operates, of trying to discern what something is but not being able to catch it, like grasping for something in motion. That movement and lack of fixity is also a serious critique of identity politics. Does that resonate?

Bass: Definitely. I think a lot about the complex relationship between humor and dead seriousness, or maybe sincerity is a better way of putting it. Serious sounds too, well, serious! All I can say is that I’m not being ironic.

Locks: It sounds like you are saying that comedy and seriousness are not opposite ends of the spectrum, but rather two sides of the same coin.

Bass: Some people will say “that is really funny” when they see my work, and other people not so much. The way the humor presents itself in the work is kind of sneaky. It doesn’t have any clear signal or cues, and it’s not predictable. It emerges through the back door, or something. But there actually is a logic.

Locks: What kind of logic?

Bass: I think it’s more productive to not scrutinize the internal logic, and to just let it wash over you as a viewer.

Locks: You would rather viewers weren’t trying to “crack the code,” so to speak?

Bass: It is frustrating when people ask me, “What does this mean,” whether it’s a symbol, an element within a painting, or the painting itself.

Locks: You mean a desire for locating a fixed meaning?

Bass: As a culture, I think we’re trained to decode visual language instead of just experiencing it. My approach to making art is coming from a place of being interested in the experiential, and just letting something be what it is, instead of trying to nail it down and hammer it into place. I’m most excited when something feels very active and slippery.

Locks: Are there other artists whose work really resonates with your thinking about your own work?

Bass: I like the way that the filmmaker Lucrecia Martel utilizes sound as the framework for her films, how she essentially starts with a sound-based score and facilitates subtle inversions with sound. The results can be terrifying. I love Leonard Cohen and how the human voice for him is a wavering, breaking one that he uses to spell out eloquent prose. His lyrics pull themselves apart in the most concise ways! There is some amazing documentation of corporeal mime pieces by Etienne Decroux that are exciting to me. There is a constant shifting of weight, balance, and isolation of the body into these slight movements, and some earlier works involve trippy, Bauhaus-inspired costuming. For contemporary art, Shannon Ebner’s work is really inspiring. I love how she is working with the weight of language, its physical structure and sculptural potentials, and also its disability. And, of course, the work of Charles Atlas, Michael Clark, and Yvonne Rainer is important to me. I am also deeply connected to the work of MPA, K8 Hardy, A. L. Steiner, Eve Fowler, Erika Vogt, Lauren Davis Fisher, Tracy Rosenthal, Alex Chaves, Sara Clendening, Ivan Morley, Lee Maida, Leidy Churchman, Sanya Kantarovsky, and Samara Golden, to name just a few.

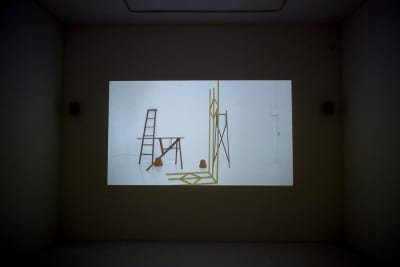

Locks: I am particularly interested in how your works create meaning when presented together. This is an obvious thing for a curator to say, but it’s important in terms of the reception of your practice as a whole. You have worked in a variety of media, starting with performance and video, then moving into painting and sculpture. In the exhibition we did together at MoMA PS1, Off the Clock (May 3–September 7, 2015), we tried to create specific moments where particular visual forms recur across works, often across two and three dimensions, to highlight the possibilities for multiple readings. Sometimes a circle is an eyeball, sometimes it’s a shadow, or maybe a hole, or the center of a flower. Or maybe it’s always all of these things at the same time?

Bass: I am interested in relationships that deal directly with multiplicity—the physical and psychic relationships between objects and images. It was exciting working together to try and find these configurations where different works were pointing at each other in discrete moments, or when they might become one singular thing, at least for a second. It’s equally interesting to me when that singularity starts to dissolve into more ambiguous signals.

Locks: What do you mean by singularity?

Bass: I think it’s circular. There are singular forms that expand through repetition and in relation to each other, and then there are these convergences where the relationships between the images and symbols step forward as a definitive moment.

Locks: There are a few key threads I see in your work. One is the ineffability of the body: how certain aspects of bodily or lived experience are inexpressible in words. Your visual vocabulary seems to approach that question, or maybe it’s more apt to say that the formal language you have developed is a possible answer. The body appears and disappears, emerges and retreats, throughout your work. When it does make itself present, however provisionally, it insists on different physical positions and angles, different orientations. To be specific, your waxed steel sculptures and your draped canvas sculptures suggest that the body doesn’t only walk, sit, and stand (like a children’s book might suggest), but it also bends, leans, splays, and crawls.

Bass: I have been thinking a lot lately about the tension between movement and stasis. The body moves; it is active and acted on.

Locks: The body is never just an image or an object, but an action or a possible action?

Bass: The body is a location. For me, there is an ongoing desire for the body to be both present and absent at the same time, or to be present in its absence.

Locks: I’m thinking back to what you said about the side of reception and feeling like there is a constant desire to find meaning that’s singular and unambiguous, so viewers can feel like they “get” it. This is a larger issue in contemporary art, but I think it’s also specific to your work, which is consciously and intentionally ambiguous. Which is not to say that your work is trying to refuse that desire, but rather that it enacts a kind of counter-ethics. It insists on multiplicity. It seems like there’s something about creating that space, about opening up possibilities, that comes from a specific place of thinking about queerness.

Bass: It probably does, but that is inside of the work, you know? It is in the work, not on top of it. It isn’t the mission of the work, but this queerness is coming through. I am queer, and I have resisted a lot of costumes and posturing that I was supposed to do in my life, or things I was supposed to stuff myself inside of. When I think of my life thus far, it was always too hard to do things that I didn’t want to do. There was an unyielding discipline that I always seemed to lack in my early years that I have been trying to reinstate in my adult life, but I don’t quite know how to do it. It doesn’t come naturally to me to fit inside any predetermined box.

Locks: I am thinking about queerness—not as an identity, more as a space for interrogating the contours of identity itself—in relation to your work because of the space that it creates. That it insists on, even. We have talked about your interest in what are actually called “ambiguous images”—the most famous examples being the duck/rabbit image, or the old woman/young woman image, or that recent Internet meme with the black-and-blue/white-and-gold dress. Your works, the paintings in particular, produce a similar ambiguity or uncertainty for viewers. Reading the work is a self-driven process, necessarily open-ended. I see it as a generous approach that is both specific and flexible.

Bass: I am thinking of queerness as a space of generosity as well: giving people space to move through the work and space to, in some respects, project themselves into the work. This is important. I think there is usually a way that the viewer’s body becomes central to the movement of the exhibition, for example, in Off the Clock.

Locks: Is it useful to think about queerness as an ethics?

Bass: I think it is.

Locks: In my own research and work as a curator, I am particularly interested in the ways that desire and the sexual operate beyond explicit depictions. Desire is everywhere. It inscribes itself in everything.

Bass: Desire is everywhere! There was a time when table legs used to signal the erotic because people were so pent up. It is weird to be living in these times when everything is hypersexualized and detached. Sometimes I feel like I am making images to slow things down, to slow down the image. That is where my desire starts to really funnel in: the desire to expand time, to slow time, and to be present, which is unmanageably hard at times.

Locks: The evocation of bodily positions and relations in your work immediately calls to mind questions of desire. This is not to say that what potentially emerges between these relations is necessarily sexual or gendered, though that argument could certainly be made. But it’s the emergence itself, the potentiality, which is a form of pleasure, at least for some of us.

Bass: I see the body in a lot of things. I guess I am looking for it as well. There is something very erotic about our eyes touching everything around us all the time, and also something unsettling about it because that power can be so easily abused.

Locks: I want to focus for a moment on your Newz! series of paintings. They are pared down and tightly composed. The fact that all of these paintings share the same title—Newz! with an exclamation point—seems kind of humorous. It’s as if the paintings are enthusiastically declaring their “newness” when the imagery is actually always very similar and repetitive, and thus they have a relatively limited vocabulary. Do you care about “the news” or about newness?

Bass: I am thinking more about information and how it is like this theater of images. I think about my paintings as spatial templates. I’m interested in how the shapes and colors vibrate in relation to each other, and how they create moments of tension and awkwardness against the groundless, raw surface. It makes sense that they would be encircled under this title that nods to the shifting of information. I find the title to be humorous. Maybe they have some weird relationship to popular news. I don’t know. It is about the generation and regeneration of images. Developing this visual vocabulary deploys a certain autism that is in a lot of the work.

Locks: In the way you have always described your process to me, it feels like the symbols coalesce into an image, and then a painting happens. This possible arrangement or orientation can occur again and again, in almost endless combinations. The repetition and multiplicity connects back to our earlier discussion of the body, identity, and a lack of fixity.

Bass: That is what keeps me interested in the series: the change through repetition and the unfixed relationships. It’s what gets me going.

Math Bass lives and works in Los Angeles. She received her MFA from UCLA. Recent solo exhibitions have been held at MoMA PS1(2015) and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles (2014). Bass’s work has also been presented at Cooper Union, New York (2015); Tanya Leighton, Berlin (2015); Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2014); White Flag Projects, St. Louis, Mo. (2014); Andrew Kreps, New York (2014); Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm (2014); and Silberkuppe, Berlin (2014).

Mia Locks is a curator based in New York. She is co-organizing the 2017 Whitney Biennial with Christopher Y. Lew at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Previously, she was Assistant Curator at MoMA PS1, where she organized exhibitions including Math Bass: Off the Clock (2015), IM Heung-soon: Reincarnation (2015), Samara Golden: The Flat Side of the Knife (2014), and The Little Things Could Be Dearer (2014). Locks co-organized Greater New York (2015), with Douglas Crimp, Peter Eleey, and Thomas J. Lax, which is currently on view at MoMA PS1 through March 6, 2016.