To read “Knight’s Heritage: Karl Haendel and the Legacy of Appropriation, Episode Three, 2013” by Natilee Harren, click here.

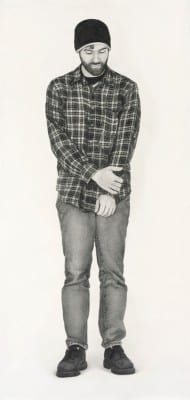

In the conclusion of her essay, Natilee Harren recounts a dramatic moment in 2013 when Karl Haendel received a copyright cease-and-desist letter from the photographer Robert Schultze, after the artist had used one of Schultze’s photos as the basis for the drawing Man (2010). It is through this confrontation that Harren reveals Haendel as a card-carrying member of the postmodernist club: an artist skeptical of the very construct of authorship, who believes that “images comprise a language as communal as the spoken and written word.” At the core of this philosophy lies an insistence on the inherent instability of the image as a “fixed” representation. Until fairly recently, this philosophy has rubbed up against copyright law’s upholding the stable image, which it couches in terms of a distinction between an idea and its expression. While an idea (such as a type of “man”) is not copyrightable, a particular expression of such an idea (Schultze’s photo) warrants protection.

This understanding begs still another question, one that Patrick Cariou’s lawyers posed to Richard Prince during his testimony at the outset of Cariou v. Prince: of all the available images that fit the need, why did the artist choose this one? In Prince’s case, it was simply a matter of whether he “love[d] the way [the image] looked.”1 No doubt the intellectual sensitivity of Haendel’s artistic rationale far surpasses that of Prince. As Harren aptly describes, Haendel is a considerate appropriationist. Yet if “all ‘types’ of images have already been produced,” as Haendel states, and therefore no one type is better than another, then the ultimate choice must be considered as one made through artistic prerogative. This freedom of choice, championed by so many artists, forms the core of an image neoliberalism. But like the related economic philosophy, it can sound much better in theory than it works in practice. Anxiety within the commercial photography industry today, for instance, has much to do with the loss of licensing revenue due to the technologically enabled free flow of images.

The good news for Haendel and artists like him is that with the recent rise of a “transformative” fair use discourse in copyright jurisprudence, the law is now more amenable to appropriation practices than it has ever been. We are witnessing what I call copyright’s “postmodern turn.” Twenty-first-century copyright doctrine may well be catching up to the sensibilities of late-twentieth-century, postmodernism. As we account for more subjectivist approaches in contemporary appropriation art, it is incumbent on artists to examine their roles as image recyclers in such a way so as not to weaken the privilege of authorship they hold dear.

Nate Harrison is an artist and writer working at the intersection of intellectual property, cultural production, and the formation of creative processes in modern media. His work has been exhibited at the American Museum of Natural History, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Los Angeles County Museum of Art;and Kunstverein, Hamburg, among others. Harrison has several publications current and forthcoming, and has lectured at a variety of institutions, including Experience Music Project, Seattle; Art and Law Program, New York; and SOMA Summer, Mexico City. From 2004–2008 he codirected the Los Angeles project space ESTHETICS AS A SECOND LANGUAGE. Harrison received the 2011 Videonale Prize and the 2013 Hannah Arendt Prize in Critical Theory and Creative Research. Harrison earned his doctorate from the University of California, San Diego with his dissertation “Appropriation Art and United States Intellectual Property Since 1976.” He received a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of Michigan and a Master of Fine Arts from California Institute of the Arts. Harrison serves on the faculty at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and lives in Brooklyn, New York.

- Greg Allen, ed., The Deposition of Richard Prince (Zurich: Bookhorse, 2012), 192. ↩