To read the first episode of “Knight’s Heritage: Karl Haendel and the Legacy of Appropriation,” click here.

Episode Three, 2013

Since the rise of appropriation in American art of the 1980s, the strategy has become so commonplace as to evade continued examination as a unique vein of artistic practice. At the same time, recurrent intellectual property battles around appropriative gestures in contemporary art have threatened its viability, giving rise to CAA’s important report published in February 2015, the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts. This three-part essay on the work of Karl Haendel, an LA-based artist best known for his arrangements of meticulously rendered drawings of found photographic imagery, connects three episodes in his early career related to issues of artistic and cultural heritage and power. The first two episodes involved knights. “Episode One” considered Haendel’s project of reconstructing works by the minimalist sculptor Anne Truitt, including Knight’s Heritage (1963). “Episode Two” concerned Haendel’s confrontation with a second artist of an older generation, the early postmodernist Robert Longo, through the artists’ drawings of the same source image of a knight. This third, final episode focuses on the relationship of Haendel’s particular mode of appropriation to contemporary image culture. Taking Haendel’s work as a point of departure and considering the digital turn, the essay as a whole examines how the operations, effects, and reception of appropriation have changed in recent decades and discovers what may be the strategy’s longest-lasting politics of signification.

“Any genuinely new trend is a knight’s move, a change of shadows, a shift that displaces the mirror.”

—Vladimir Nabokov

The year 2013 found one of Karl Haendel’s drawings of knight’s armor hanging amid a room-sized installation of several drawings mounted by the artist at the Indianapolis Museum of Art. Haendel’s display was part of Graphite, a group show focused on artists who work in various ways with that material: carbon in crystalline form. His drawings were hung corner to corner, edge to edge in a wonky daisy chain of images that meandered from side to side and floor to ceiling across the four walls of the semi-enclosed gallery. The idiosyncratic arrangement willfully avoided conventions of height and spacing, and the painted walls—three in varying shades of deep, warm gray and the fourth a lurid bubble-gum pink—emphatically treated the drawings as part of a cohesive program rather than a succession of singular pieces.

As I argued in “Episode Two” Haendel’s practice of arranging drawings in loosely associated groupings follows a kind of knight’s-move thinking—indirect, even devious in its linking together of disparate things—that hopes to coax certain meanings from a body of visual material, both appropriated and self-made. Haendel’s Indianapolis installation was no exception, and it furthermore advanced his project of investigating contemporary models of masculinity and male subjectivity. In the show, Knight #1 (2010), one of a series of eight life-sized drawings of medieval armor that Haendel produced as a meditation on the debilitating effects of emotional distancing in men, appeared alongside a series of other drawn images that collectively evoked the fragility of male power. Towering over Knight #1 to the drawing’s left was an enormous upright rocket that was actually a grossly oversized rendering of a toy model. Two smaller drawings were mounted below, their edges touching those of the grandiose knight and rocket, yet they offered unconvincing support—one a pathetic-looking Humpty Dumpty figurine perched atop a fence, the other the amoeboid form of a broken egg. On the wall opposite, Haendel arranged scenes, icons, and language around the theme of hands and manual forms of labor: an abstract scribble, a longshoreman’s union poster featuring a clenched fist, a hand reaching down to “stretch” a can of sugar in a bit of WWII propaganda promoting wartime rationing. Two soot- or graphite-blackened hands, presumably the artist’s own, were depicted resting passively atop a spread of unmarked paper. Pairs of ampersands featured as well, an alliterative underscoring of the theme of hands as well as a reminder of the associative logic at play throughout.

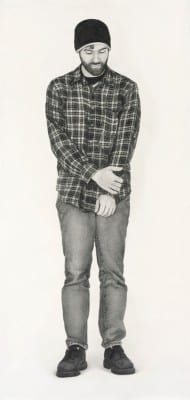

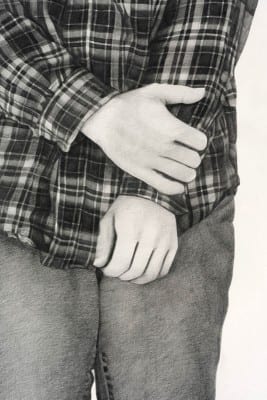

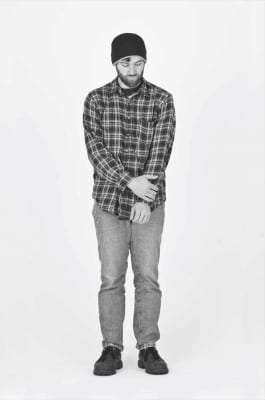

In aggregate, these visual details conjured a model of American masculine identity and attendant forms of manual labor that have been undermined in our neoliberal age by the outsourcing of manufacturing jobs from this country and the transition to an information and service economy. Haendel pictured the affected demographic explicitly. Leaning against the wall at floor level among the grammar of hands was a drawing of the very figure of the young worker—a bearded man wearing a wool cap, flannel shirt, jeans, and work boots. Gazing despondently at the ground as he clutches one slack arm close to his body, his posture is one of defeat. His hands are not occupied by work. What’s more, the paper on which the image is drawn was mounted bare and unframed on a panel, propped against the wall as if uncertain as to its final placement.

This man—Man (2010)—was in a sense the corollary to Haendel’s knights. Although opposite to the knights in the figure’s posture of vulnerability, Man nevertheless signified for the artist a similar subject position—damaged, weak, unheroic. Man is “a common and somewhat impotent-looking guy.”1 The drawing is based on an image taken by the San Francisco–based photographer Robert Schultze that Haendel found on the Internet, not even on Schultze’s own website but from some long-forgotten intermediary site where it had been reposted. It is unsurprising that Haendel was attracted to the image, not just because it so well personified a certain model of male subjectivity the artist was exploring at the time, but because it already looked uncannily like a Haendel graphite drawing with its rich gray tones highlighted against a stark white backdrop.

Before Indianapolis, Haendel’s Man had already appeared in a 2012 solo exhibition at Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Informal Family Blackmail, where it was similarly meant to evoke contemporary experiences of emasculation. There, it was positioned directly across from a life-size drawing of an item of contemporary women’s fashion, a military-style floor-length coat, which invited projective imaginations of what kind of woman might wear such a high-powered piece of clothing. The juxtaposition of Haendel’s Man and Long Black Coat (2012) begs comparison to Robert Longo’s Untitled (Adam and Eve) (discussed in “Episode Two”), which would appear later that year at Art Basel Miami Beach. Both duos reproduce gender stereotypes loosely indexed to the periods in which Longo and Haendel came of age. The gendered power dynamic symbolized by Longo’s male knight and female bombshell is in Haendel’s oeuvre inverted, with the dejected Man playing the counterpart to the Long Black Coat, a stand-in for those legions of empowered, bread-winning women who have spelled our age’s celebrated/reviled “End of Men.”2

In both appearances of Haendel’s Man, in Los Angeles and Indianapolis, the drawing stood for a type of man and an associated notion of masculinity. As we know of Haendel’s images, drawn—in two senses: both culled and reproduced—from an archive organized according to a constantly expanding typology (Ampersands, Cracked Eggs, Doodles, Exclamation Points, Hands, Politicians, and so forth), such a man takes his place as one type among many other generic types of things, objects, concepts, people, or beings. Haendel’s practice of exhibiting drawings in carefully arranged groupings serves to highlight certain connotations of individual images, and these connotations can shift depending on the overall composition of the group—both its content and how that content is arranged. In Los Angeles, Man’s role as an emblem of contemporary masculinity was contrasted with a vision of contemporary femininity, while in Indianapolis, that same emblem of masculinity took its place among varied representations of blue-collar labor. Man stands for more or less the same type in both cases, but Haendel is asking us to think about it from different points of view.

As becomes clear from the example of these two installations, the connotations of Haendel’s drawn types are elaborated and nuanced in various ways as they fit into different exhibition configurations. But they remain, after all, types. There was, however, at least one visitor to Graphite for whom Man absolutely could not be perceived on such an abstract register, and that was the very man who had posed for the original photograph from which Haendel made his drawing. That man happened to visit the show only to find, to his surprise, a life-size photorealistic drawing of himself. One imagines the encounter was at least as affecting and uncanny as when Haendel encountered for the first time, similarly without anticipation, Anne Truitt’s sculpture Knight’s Heritage (1963), which the artist had laboriously reconstructed during his graduate school days without the benefit of ever seeing the work in person (discussed in “Episode One”).

Following the man’s unexpected encounter with his drawn image, the original photographer, Robert Schultze, decided to confront Haendel about his brazen appropriation. In August 2013, a man identifying himself as Schultze’s agent sent a cease-and-desist letter to Haendel’s Los Angeles gallery, copied also to the director of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, which argued that Haendel’s drawing constituted copyright infringement. The agent demanded Haendel either “recall any and all copies of the artwork and send [the] original and any and all editions to Mr. Schultze,” or pay a one-time licensing fee of $10,000. “Frankly this painting used by Mr. Haendel is a dead ringer for Mr. Schultze’s Photograph,” the letter stated, further citing precedent intellectual property cases from the 1990s (Pasillas v. McDonald’s, 1991, and Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. Penguin Books, 1997). “The rendering by Mr. Haendel is literally an identical copy is [sic] almost every detail, in that the perspective, pose of the model, setting, lighting, and color of the background and overall esthetic are virtually the same.” Remarkably, while the letter obsesses over the details of the visual correlations between Haendel’s drawing and Schultze’s photograph, it speaks nothing of their material differences and repeatedly misidentifies Haendel’s drawing as a painting: “There is no question that the lay observer would recognize Mr. Haendel’s painting as having been appropriated from the Mr. Schultze photographic image.”3

We have seen similar confrontations before, from the high-profile litigation brought in recent decades against appropriation work by Jeff Koons and Richard Prince to the debates that unfold daily in our classrooms. Artists and art historians with aspiring commercial photographers among their students commonly witness a version of this standoff in the course of discussions of appropriation art of the 1980s and beyond. Schultze’s position holds that a visual expression belongs unequivocally to its author, while from the perspective of Haendel’s practice, images compose a language as communal as the spoken and written word. Haendel claims to maintain a thoroughly postmodern skepticism toward the construct of authorship, presuming that artistic expression is always-already a reconfiguration of existing tropes and that meaning is derived predominately from the work’s context of appearance. In the oft-cited words of Douglas Crimp, “Underneath each picture there is always another picture.”4 What is new, as Nate Harrison has argued (and as I discuss in “Episode Two”), is that the canonization of the appropriative practices of certain high-profile artists has led to “the reassertion of authorship in postmodernity”—a belated instatement of a metaphysics of presence centered paradoxically on the deconstructionist operations critics had once claimed for this work.5

The opposed attitudes about authorship and appropriation represented by the positions of Schultze and Haendel in this case (which I am suggesting may not in fact be so far apart) have only become more extreme in today’s image-saturated culture. If appropriation has become easier due to the proliferation and dispersion of visual material through digital means, intellectual property litigation has only become more aggressive.6 To give a most famous example, at the time Haendel was considering how to respond to Schultze’s demands for remuneration, the Second Circuit court case was unfolding between the French documentary photographer Patrick Cariou and Richard Prince, who had appropriated Cariou’s photographs of Rastafarians for his Canal Zone series of paintings exhibited in 2008 at Gagosian Gallery, New York.7 The case, initially lost by Prince, was successfully appealed by the artist and his gallery in April 2013, with the court ultimately finding twenty-five out of thirty of Prince’s appropriations acceptably transformative. Five works deemed not sufficiently transformative were remanded to district court for further deliberation, but the case was ultimately settled out of court in March 2014.

Had Haendel’s confrontation with Schultze taken place in the wake of full public awareness of the Cariou v. Prince outcome, he may have found surer legal footing from which to rebuff Schultze’s threats of litigation.8 For in that case’s appeal, the court decided that most of Prince’s works in fact did qualify as fair use “despite the fact that both the collage and the original photographs served similar expressive purposes, albeit in very different manners.”9 In the Harvard Law Review’s analysis, the court’s broadened definition of fair use effectively relaxed “the requirements for transformativeness such that a work need only show ‘new expression, meaning, or message.’”10

Still, law scholars have seen Prince’s win as a mixed blessing. Although he prevailed, it was only on the basis of a side-by-side visual comparison between Prince’s works and Cariou’s photographs. The logic of that evaluative procedure—referred to as the Cariou test—is problematic in that it “reduces the inquiry to a facial examination of the physical differences between two works.”11 The result is an overly literal understanding of what qualifies as a transformative act of appropriation, and thus a potentially limiting precedent set for future artists working in this mode. Furthermore, as the Harvard Law Review states, “There is no clear, workable distinction between the amount of new expression sufficient for copyright protection and the level of new expression, meaning, or message sufficient to render a piece transformative under the Cariou test.” A wary conclusion follows: “The Cariou decision itself represents a tonal shift in the approach of the Second Circuit toward appropriation art, and the majority was willing to note that the art community at large has embraced the genre. However, there is no guarantee that the milieu will not tilt back in the other direction.”12 Indeed, despite this shift in the interpretation of fair use ostensibly in favor of appropriation practices like Haendel’s, the artist’s private confrontation with Schultze resulted in skeptical questions from some of his supporters about the necessity of the bald appropriation tactics arguably crucial to his practice, with some calling for more obvious gestures of transformation. To take a cynical view, this may be a partial explanation for the recent turn in Haendel’s work toward irregularly shaped frames, the translation of drawings into sculptural objects, and increasingly experimental installation programs.

While these legal debates can be fascinating, I want to turn to more aesthetic and semiotic questions that might be asked of Haendel’s work. Mainly: what exactly was Haendel copying in his appropriation of Schultze’s image? Surely from what we know of his practice, the gesture cannot be reduced to the re-presentation of an image merely in its denotational sense. As I have already argued, Haendel’s grouped drawings invite us to see everyday images through the matrix of general categories or types which we may then compare, one type to the next. What Haendel appropriates is not only an image in and of itself but also its metonymic relations to an entire class of like things. For example, via his Little Legless Longos (miniaturized copies of Longo’s Men in the Cities drawings, discussed in “Episode Two” of this series), Haendel is able to incorporate into his image inventory the entire practice of Longo, as well as its aesthetic and historical implications. Through the addition to an exhibition grouping of a single one of these drawings, Haendel can evoke all at once and in an extraordinarily succinct manner the entire genre of appropriation art, the medium of drawing, and his own place within art history as a second-generation postmodernist. In this way, Haendel invites the viewer to consider quite singular images as iconic representations of a type. In his words, “I never looked at Robert Longo and was like oh, someone else has done big black and white drawings, so I better not. It was like well, I can pick up a Robert Longo book. I can listen to NPR. I can open a newspaper. I can watch football. They’re all equal. They’re all input. Robert Longo is the same to me as turning on a television.”13 While Haendel’s images are ripped from their original, immediate contexts, he is not interested in leveling meaning or obliterating their referential value (although this can sometimes be the effect of a particularly weak or obscure grouping). Rather, his practice of arranging images anew seeks to reframe them as part of a much broader cultural imaginary.

In Haendel’s post–Pictures Generation logic, visual culture is comprised of a series of ‘codes’ that are or can be made “mutually accessible, navigable and understandable.”14 His image constellations confront us with the very processes of discernment by which we recognize, distinguish, and interpret the rich image ecology that surrounds us. This is what is meant when Haendel’s practice is described, as it often is, as syntactical. His work distills visual narratives and associations that have been spun in popular culture and delivers them back to us as a newly perceptible code. Haendel’s mode of appropriation helps us see the semiotic operations of image culture through an ostensibly simple act of repetition, as an infant’s doubling of phonemes—ma and pa into mama and papa—marks the passage from babble into language.

But how, more precisely, do we discern the meaning of an image, particularly one that asks to be read as a type? To discern is to observe the limit between a thing and its other or outside. Discernment involves a process of abstraction, of removal or extraction, in which a thing is considered theoretically, apart from its immediate context, as we relate it to our prior knowledge of like and unlike types. It is in terms of such processes of abstraction that I want to understand the transformative quality of Haendel’s appropriations, as well as the difference between Schultze’s image and Haendel’s Man: the former becomes the latter via a gesture of abstraction, as Haendel calls us to discern Man as a type, a metonym for a larger category of subjects. Recall, as I stated in “Episode One”, how Truitt’s early fence-like sculpture First (1961) defined for us a model of metonymic abstraction “in which the abstract becomes a synonym for the generic, a model in which form—for Truitt, shape in concert with color—becomes typological, stripped of all but its most essential, characteristic elements in order not to transcend the world but to relate ever more capaciously to it.”15

There is no more problematic arena in which we discern and discriminate, of course, than in and through our encounters with others. The individual person subject to an abstracting regard is so often the victim of an act of symbolic if not real violence. Thus it should not be surprising that in so many of the fair use cases that have touched on the art world, the accusation of copyright infringement has centered on works that feature the human figure. This was certainly the case with Man. Framed by Haendel as a type—the young worker—for Schultze and his model the image remains absolutely singular, indexed to the body of the man who had posed for the original photograph.

Yet, the abstraction of subjectivity into types, categories, profiles, or demographic data points able to circulate in a monetized information economy is a phenomenon and process in which twenty-first-century subjects increasingly, willfully participate. We have arrived at a moment in which the subject matter we consider art-historically to be most resistant to abstraction—the human figure—has been rendered thus in the terms given to us by our contemporary political economy, and artists, Haendel among them, have begun to register this in their work. As George Baker writes, “While we are increasingly surrounded by all sorts of representational images . . . in contemporary art, what we are in fact surrounded by are abstractions, as blank and as open as the monochrome was in another, now increasingly distant, historical age.”16 Baker convincingly draws on Fredric Jameson’s theorizations of the relationship between the cultural and economic forces of postmodernism and finance capital to explain what has made these hermetic modes of what we might call “figurative abstraction” possible. “Modernist abstraction comes about only in a social situation of incomplete abstraction, while the postmodern return to figuration is the cultural expression of an epoch of total or complete abstraction (although this totality can in turn be questioned), an expression of the new freedom to recode and, to use the Deleuzian word that Jameson chooses, deterritorialize all residual content.”17

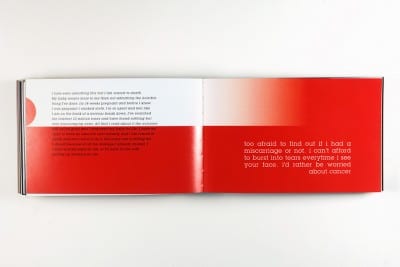

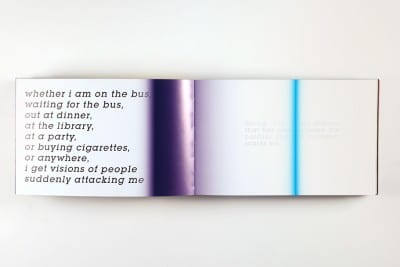

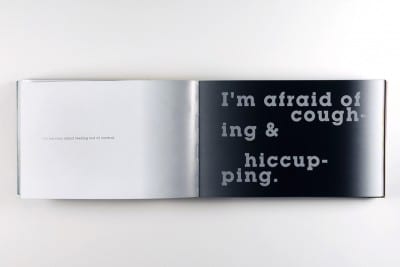

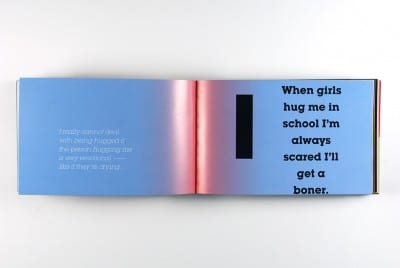

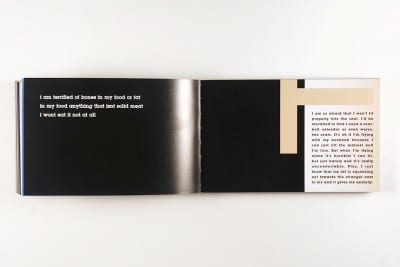

In this genre of artwork, the codes that structure our reception of (mainly) photographic images are mined and reconfigured in illuminating, peculiar, and, at best, critical ways. We see this not only in Haendel’s work in the ways I have already described, but in the uncannily depleted, quasi-anonymous still-lifes and portraits that populate the photographic work of Haendel’s Los Angeles contemporaries such as Charlie White, Matt Lipps, and Elad Lassry, or that of an older generation including Christopher Williams and Barbara Probst.18 (Less compelling versions of this phenomenon can be found in the randomized, Tumblr-esque aesthetic of much so-called Post-Internet art.19 ) Often borrowing the language of commercial photography, these artists picture in various ways the flattening of identity into many categories, types, demographics, and profiles—many iterations of the human subject submitted to some process of abstraction into a type, whether economic, social, cultural, racial, etc. In his artist books Fear (2013) and Shame (2014), Haendel has also explored the effects of this condition on language, communication, and intimacy by surveying online discussion forums and anthologizing the highly personal and emotional confessional statements disclosed by users only under the cover of anonymity. When reading highly personal accounts that have been dislocated from their authors, the reader finds him or herself imagining the type of person to which each statement belongs. Haendel has furthermore arranged the statements in progressions that invite comparative, evaluative modes of reading.

In his cease-and-desist letter to Haendel, Schultze’s agent explicitly references the 1991 copyright infringement case Pasillas v. McDonald’s, whose verdict refers to a procedural “intrinsic test,” first established in 1977, for determining whether copyright infringement has occurred. An intrinsic test “focuses on similarity of expression and asks whether the ordinary reasonable person would find ‘the total concept and feel of the works’ to be substantially similar.”20 It is on the basis of this language that the agent’s letter declares, as quoted above, “There is no question that the lay observer would recognize Mr. Haendel’s painting as having been appropriated from the Mr. Schultze photographic image.”21 However, elsewhere in the Pasillas v. McDonald’s verdict it is stated that “no copyright protection is afforded to elements of expression that are indispensable or standard in treatment of idea.” Theoretically, if we understand Haendel’s strategy to be one of collecting and recontextualizing generic types already locatable within the image ecology, such a defense could be made of his appropriations. All the visual elements of the figure depicted in Man, along with the original photograph’s existence as part of a readily accessible image commons, are what make it “standard” in the terms set forth by Haendel’s practice. If a type is defined by the very indispensability of its standard set of features, then the characteristics isolated by Schultze’s agent as the photograph’s unique and thus copyrightable features—“the perspective, pose of the model, setting, lighting and color of the background and overall esthetic”—are recognized by Haendel as being, in fact, not unique at all. Simply ask yourself: How many times have you seen this man before? Or a version of him?

In a recent meditation on the meaning of appropriation for the field of art history in general, Elizabeth Edwards writes, “Photographs accrue meanings as they move through different spaces, for, after all, appropriation entails the politics of categories.”22 If photography is a medium historically associated with the documentarian’s desire to catalogue and control, Haendel’s constellations of images redrawn from photographs engage similar procedures, but in an experimental manner that probes the limits of common understandings of what images can mean, both singularly and in relation to one another. This was no more evident than in Haendel’s recent series of yoga drawings featured in a 2015 solo exhibition at Los Angeles’s Night Gallery, Unwinding Unboxing, Unbending Uncocking. In these works, roughly life-size drawings of women holding different yoga poses are contained in irregularly shaped frames. The women’s highly sculpted bodies conform awkwardly to the abstract geometries of their containers, with the frames cutting into their bodies in some instances and avoiding contact with them at others. The frames render the contours of the poses into tidy, iconic shapes, graphic imprints that visualize very plainly how abstract forms of discipline and control—here the New Age dispositive of yoga as it has been received in the United States—literalize themselves in, on, and through the body.23 Haendel shows us the impossible gap between the human subject and the abstract types we have been conditioned to aspire to and identify with.

Haendel’s work is most difficult to apprehend in these moments, when it seizes on cultural meanings that have not quite achieved the status of type, or when the social dynamics and aesthetic imaginations they disclose are so basic to contemporary experience that they remain nearly invisible to us. But, remarkably, Haendel’s odd framing of the women’s bodies helps us begin to see them as if from a historical distance, in advance of the time when such distance becomes possible. I want to argue, finally, that Haendel’s image arrays stage an encounter with types in becoming, or the becoming-type: the process by which an image becomes a generic type, the process by which a form begins to imply a whole class of forms, objects, people, or things. The work confronts us with the processes of abstraction by which we come to systematize and formalize as knowledge what mass culture has already taught us intuitively, processes that establish the recursive pathways for future thought and forms of being. “Any genuinely new trend is a knight’s move,” Nabokov wrote, “a change of shadows, a shift that displaces the mirror.”24 In their least compelling moments, Haendel’s appropriations and recontextualizations simply reinscribe the brutish contours of cultural stereotypes or threaten to cashier meaning and referentiality altogether. At their best, however, they remind the individual viewer of his or her power to actively intervene in culture’s knight’s moves.

The epigraph is from Vladimir Nabokov, The Gift, trans. Michael Scammell (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1963), 228.

To read Nate Harrison’s response to this essay, click here.

Natilee Harren is assistant professor of contemporary art history and critical studies at the University of Houston School of Art. Her research engages experimental, interdisciplinary practices after 1960, with particular emphasis on intermedia art and theories of translation between artistic mediums and disciplines; the role of notations, scores, and diagrams in conceptual and performative art practices; institutional critique; social practice; and theories of appropriation. Her current book project, “Objects without Object: Fluxus and the Notational Neo-Avant-Garde,” examines the work of the international, neo-avant-garde Fluxus collective amid transformations of the art object wrought by score-based practices of the 1960s and the epochal shift from modernism to postmodernism. Harren is also coeditor of a critical anthology, forthcoming from the Getty Research Institute, which surveys and theorizes a range of twentieth-century experimental notations from the fields of performance art, dance, literature, and music within a media-rich digital platform. Her essays and criticism have appeared or are forthcoming in Art Journal and Getty Research Journal, among other publications, and she has been a regular contributor to Artforum since 2009.

- Karl Haendel, unpublished transcript of a lecture delivered in the Visual Arts department, University of California San Diego, 2013. ↩

- Hannah Rosin, The End of Men: And the Rise of Women (New York: Riverhead Books, 2012). ↩

- Letter from Norman Maslov to Karl Haendel, August 20, 2013. ↩

- Douglas Crimp, “Pictures,” in Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation, ed. Brian Wallis (New York: New Museum, 1984), 186. ↩

- Nate Harrison, “The Pictures Generation, the Copyright Act of 1976, and the Reassertion of Authorship in Postmodernity,” Art&Education Papers, at http://www.artandeducation.net/paper/the-pictures-generation-the-copyright-act-of-1976-and-the-reassertion-of-authorship-in-postmodernity/, as of July 22, 2015. ↩

- Siva Vaidhyanathan, Copyrights and Copywrongs: The Rise of Intellectual Property and How it Threatens Creativity (New York: New York University Press, 2001). ↩

- Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694 (2d Cir. 2013). ↩

- Haendel was able to settle with Schultze out of court for a far lesser sum than the $10,000 the photographer demanded and without having to relinquish any of his artwork. Haendel’s recent efforts to reconnect with Schultze to open up a dialogue between the two artists around the publication of this essay received no response. ↩

- “Cariou v. Prince: Second Circuit Holds that Appropriation Artwork Need Not Comment on the Original to Be Transformative,” Harvard Law Review 127, no. 4 (February 2014): 1228. ↩

- Ibid., 1228. ↩

- Jonathan Francis, “On Appropriation: Cariou v. Prince and Measuring Contextual Transformation in Fair Use,” Berkeley Technology Law Journal 29, no. 4 (2014): 710. Francis’s arguments advance, in the wake of Cariou v. Prince, claims made compellingly by Laura A. Heymann in her article “Everything Is Transformative: Fair Use and Reader Response,” Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts 31 (2008): 445–66. Interestingly, Anne Truitt has compelling wisdom to offer on the problem of divorcing works of art from their discursive contexts and evaluating them at face value: “No one questions the fact that verbal language has to be learned, but the commonplaceness of visual experience betrays art; people tend to assume that, because they can see, they can see art.” Anne Truitt, Daybook: The Journal of an Artist (New York: Scribner, 1982), 133, entry dated 17 Feb 1975. ↩

- Nate Harrison makes a set of related observations in his recent essay “What is Transformative,” Enemy Reader 2, no. 2 (2015), at http://theenemyreader.org/what-is-transformative/, as of September 22, 2015. ↩

- Karl Haendel and Aram Moshayedi, unpublished conversation, May 7, 2013. ↩

- Haendel, “Complicated Sneakers,” 83. ↩

- Natilee Harren, “Knight’s Heritage: Karl Haendel and the Legacy of Appropriation, Episode One, 2000,” Art Journal Open, at http://artjournal.collegeart.org/?p=6929, as of June 13, 2016. ↩

- George Baker, Gerard Byrne: Books, Magazines, and Newspapers (New York: Lukas and Sternberg, 2003), 42. The main Jameson text to which Baker refers is “Culture and Finance Capital” (1996), The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983–1998 (London: Verso, 1998). ↩

- Baker, 77–8. ↩

- Recent exhibitions including Perfect Likeness: Photography and Composition (2015), curated by Russell Ferguson at the Hammer Museum, and Ordinary Pictures (2016), curated by Eric Crosby at the Walker Art Center, have offered welcome opportunities to think through these questions and comparatively evaluate this body of work more closely. ↩

- I am thinking, for example, of much of the content one finds on the digital platform DIS Magazine (http://dismagazine.com), or the individual practices of artists such as Yung Jake, Petra Cortright, Ryan Trecartin, and Lizzie Fitch. Elsewhere, I have expressed my reservations about the (anti-)politics of the collaborative work of the latter two artists. See Natilee Harren, “Ryan Trecartin & Lizzie Fitch at Regen Projects,” Artforum (January 2015): 219–220. ↩

- Pasillas v. McDonald’s Corp., 927 F.2d 440, 442 (9th Cir. 1991). ↩

- Letter from Norman Maslov to Karl Haendel, August 20, 2013. ↩

- Elizabeth Edwards, “Notes from the Field: Appropriation: Back Then, In Between, and Today,” Art Bulletin 94, no. 2 (June 2012): 171. ↩

- For Michel Foucault’s elaboration of dispositive, see Foucault, “The Confession of the Flesh” (1977), in Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 194–228. ↩

- Vladimir Nabokov, The Gift, trans. Michael Scammell (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1963), 228. ↩