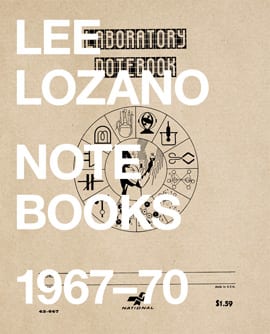

Lee Lozano. Lee Lozano: Notebooks 1967–70. New York: Primary Information, 2010. 224 pp., 108 b/w ills. $24

Lee Lozano. Lee Lozano: Notebooks 1967–70. New York: Primary Information, 2010. 224 pp., 108 b/w ills. $24

“HISTORY DRAGS.” Of the many shrewd observations and witticisms that Lee Lozano (1930–1999) recorded in her notebooks, this one strikes deepest when considering the revival of interest in her work. Of course, we’ll never know her opinion on the widespread, international attention that has been lavished on her art and life over the last decade. Or whether she’d care much about the recent, high-profile exhibitions of the works she made during her short career in New York, from the mid-1960s to 1972. But it’s doubtful that she would. Indeed, it’s hard to think of another artist who has been so fervently resuscitated and yet who so decisively rejected fame, a career, and the art world. Perhaps her phrase “Win First Don’t Last, Win Last Don’t Care” might seem a more appropriate starting point, but one wonders what Lozano would think of that one, too, since it was used for the title of one of her posthumous retrospectives.

The story of Lozano’s rejections and her art-historical status is not my interest here. Eight years ago in these pages, Helen Molesworth aptly charted those waters, noting how Lozano fell into “art world obscurity” when she abandoned the “institutions of art buttressing her activities.”1 Lozano is known, if at all, for her mythic and extreme performances: She announced her staged withdrawal from the art world in her General Strike Piece, 1969, and dropped out completely around 1972 to move to Dallas. Molesworth argued, “It is only now, with the excavation and attention of curators, critics, and art historians, that her work can be recognized and legitimated.” And this is what has happened.

Over the last decade Lozano has been featured in several major museum surveys and their accompanying catalogues—from WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution to High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting 1967–1975. There have also been three large-scale solo exhibitions devoted to her work: at MoMA PS1 in 2004, at Kunsthalle Basel in 2006, and most recently at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 2010. All this attention raises some questions: What lies behind the peculiar process of recovery and the pressure to amend the art-historical canon? And what are its costs? Has Lozano’s “enigma,” which is so often evoked, been undermined through these exhibitions and publications? If so, how can we now address the demand for privacy that, I would argue, informs her best-known works? What might this dialectic between the individual’s need for privacy and the art world’s reliance upon publicity help us understand about Lozano—and other artists like her—who ultimately withdrew from art into life?

These thoughts came to mind when the small nonprofit imprint Primary Information published a compilation of Lozano’s “laboratory” notebooks in March 2010 with the permission of her estate at Hauser & Wirth.2 The simple, no-frills volume comprises only scanned selections from her notebooks, and therein a number of complicated, telling, and diaristic observations recorded by the artist between 1967 and 1970. It also includes studies for her abstract paintings, many of her decisive Language Pieces, and brief notes, such as this emblematic entry: “FEB 3, 68: I HAVE STARTED TO DOCUMENT EVERYTHING BECAUSE I CANNOT GIVE UP MY LOVE OF IDEAS” (the book is not paginated).

Of the three notebooks that Primary Information has reproduced, one is marked “private.” This might seem a minor point to dwell on, given that several of the works in this particular notebook have already been exhibited and reproduced in catalogues. But as it appears in the Primary Information reprint, a whole notebook rather than single works, it poses a significant problem for Lozano’s revival: that of finding a balance between the artist’s wishes—or the tropes of privacy and the personal within the work—and the demands of the historian, the art market, and the estate. What is one to make, for example, of the recent publication by A.R.T. Press of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s snapshots of his cats, apartment, toy collection, and trips to Florida?3 On the surface, these are less confidential than Lozano’s notebooks, yet the personal and brief observations that he wrote on the back of the photographs resonate deeply with her observations. Did Gonzalez-Torres want these to be published? And thus, are these “works”? We’ll never know.

Posthumously published writings—from Van Gogh’s letters to Steven Parrino’s No Texts—are undoubtedly useful and insightful, as they offer a glimpse into the artist’s internal monologue. Yet they also call into question the way personal writings and ephemera—basically everything—become public over time, or as Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner argue, “There is nothing more public than privacy.”4 Why do artists keep journals? On the one hand, the urge to record thoughts is a natural impulse, and on the other, it seems that some diaries are meant to be seen and are made, perhaps, in service to the archival impulse.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. In this particular notebook is Lozano’s Dialogue Piece, 1969, which is emblematic of her need both to record and to keep some aspects of her life private. For the work, the artist invited guests to her studio and then documented the meeting through cryptic notes, such as: “MAY 30, 1969: DAN GRAHAM AND I HAVE AN IMPORTANT CONVERSATION IN THAT DEFINITE CHANGES WERE IMMEDIATELY EFFECTED BECAUSE OF IT.” Clearly Lozano is withholding information about the conversation and its import, but from whom? Surely not all of the conversations were remarkable, but one senses a palpable desire to keep certain details at bay here—to retain some boundary between art and daily life. Lucy R. Lippard picked up this deferral of information in her catalogue essay for the Moderna Museet’s show, which was curated by Iris Müller-Westermann and featured several of Lozano’s language pieces in a corridor between galleries of her paintings from the late 1960s and early 1970s. Lippard focuses on the “incredibly personal” aspects of Lozano’s art. She writes:

At a time when Conceptual artists were outdoing themselves in dematerializing their objects and their activities, competing as to who could do less and still call it art, Lee outdid them all by doing less with an unmatched intensity that made it more. . . . The contradiction at the heart of Lozano’s text pieces is that we are told a great deal about her actions and very little about their ramifications. . . . Her conceptual works are incredibly personal and at the same time models of privacy. She treated herself and her life as an objective experiment. Exposés on her activities and feelings were carefully selected.5

The relationship between Lippard and Lozano was brief but significant: Lippard included Lozano’s Piece, her first exhibited conceptual work, in Art/Peace, an antiwar event at the New York Shakespeare Festival/ Public Theater in 1969.6 In 1971 the artist began to boycott the critic, as noted in this opaque entry:

1ST WEEK AUGUST, 71: DECIDE TO BOYCOTT WOMEN. THROW LUCY LIPPARD’S 2ND LETTER ON DEFUNCT PILE, UNANSWERED. DO NOT GREET ROCHELLE BASS IN STORE. 2ND WK AUGUST, 71: PAULA RAVINS CALLS AUG 11. TELL HER I AM BOYCOTTING WOMEN AS AN EXPERIMENT THRU ABT SEPT. & THAT AFTER THAT “COMMUNICATION WILL BE BETTER THAN EVER.”

Lozano’s boycott echoes the rejections at play in her General Strike Piece (against capitalism, the art world, and patriarchy, as Molesworth has written), but one might also consider her desire for privacy too. The artist’s Wave paintings were on view in her solo show Lee Lozano–Painter at the Whitney Museum (December 2, 1970–January 3, 1971), which was installed just a month after a feminist offshoot of the Art Workers Coalition, the Ad Hoc Women Artists’ Committee, of which Lippard was a key member, held a demonstration at the museum in protest of the Whitney Annual.7 What would motivate Lozano to protest a museum that planned to feature her work so soon—even if many of her (mostly male) friends were participating in such actions? I’d like to suggest that her personal boycott was not fueled by an antipathy toward the committee or toward women in general, but instead that it was part of a larger need to keep certain ideas concealed until “abt sept.” and perhaps, until her peers could empathize with her position, which she had stated in 1969: I WILL NOT CALL MYSELF AN ART WORKER BUT RATHER AN ART DREAMER AND I WILL PARTICIPATE ONLY IN A TOTAL REVOLUTION SIMULTANEOUSLY PERSONAL AND PUBLIC.8 That never happened, however: Lozano continued to boycott women until her departure from New York in 1972. Just when Lozano withdrew from the art world, Lippard registered some of Lozano’s major contributions in the seminal book Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972.9

Undeniably, Lozano’s preference to withhold information as seen in her conceptual pieces also stresses her desire to use language as a screen and to highlight the impenetrability of private encounters. This is in contrast to the apparent linguistic transparency in some conceptual works of the era, such as those of Joseph Kosuth. But, as Lippard writes, Lozano ultimately used her life as an experiment. Herein resides one of the greatest contradictions of her art.

Many of the original pages from Lozano’s notebooks, including Dialogue Piece, were on view in the Stockholm exhibition, yet several copies were also presented. A few recent group shows have likewise featured such reproductions; to cite but one example, an exhibition at Andrew Kreps Gallery in New York, concurrent with the Moderna Museet show, included two of Lozano’s facsimiles in a gathering that paired her work with Stephen Kaltenbach’s. The fact that Lozano produced several versions of the works she made in her notebooks, beginning with Piece, and then distributed them to friends in “small but unknown quantities,” according to the writer Todd Alden, makes matters very complicated.10 (In addition, in July 1969 she submitted Dialogue Piece and General Strike Piece to the sixth issue of Vito Acconci and Bernadette Mayer’s publication 0 to 9.) Lozano made photocopies, carbon copies, and “wet” copies of her language pieces using a technology that resulted in a hard-to-read print, which she then photocopied. One assumes that she considered these distributed copies finished works, yet they retain an unfinished, sketchlike quality—clearly the idea was paramount. The “final” versions, according to the estate, are in the three notebooks reproduced by Primary Information as well as on loose sheets of paper.

Seen together, Lozano’s published notebooks do possess the sense of the privacy and intimacy of Gonzalez-Torres’s snapshots, and the exhibited copied pages, on their own, are more analogous to a work like On Kawara’s 1968–79 postcard series I GOT UP, with its friction between the artist’s reticent transmission of information and his desire for self-promotion through oblique methods. When we look at Kawara’s works, however, what is most fascinating now are the recipients—the constellation of artists, dealers, critics, and curators who comprise the network of the art world in that era. While reading Lozano’s copied notebook pages, one notes the obverse. For instance in Dialogue Piece, Robert Morris, Carl Andre, Larry Poons, Lawrence Weiner, Yvonne Rainer, John Giorno, Claes Oldenburg, and many more are mentioned as participants, yet there is little reference to anyone receiving copies of the work, which seems strange, since Lozano documented every visit so carefully. In the few instances when she does mention sending out a copy, it is as marginalia, as in one of the reproductions of Take Possession Piece #3, 1969. At the very bottom of the page Lozano wrote: “CC—ABOUT HALF A DOZEN PEOPLE,” and, to the right of that inscription, “FOR DAN—AN ORIGINAL—WITH MUCH LOVE.”

This slippage between the public and private—and to be sure Lozano’s art seems to reframe the meaning of both—reminds me of a passage in David Rieff’s preface to Reborn, a collection of journals and notebooks written by Susan Sontag, his mother, from 1947 to 1963. It is “not the book she would have produced,” he notes, adding: “that assumes she would have decided to publish these diaries in the first place.” Rieff then draws a parallel to Sontag’s speeches and lectures, which appear in At the Same Time, a volume published two years after her death. “Despite the fact that my mother certainly would have substantially revised the essays for republication, they had already been either published during her lifetime or delivered as lectures. Her intentions were clear.”11

For those who are working to revive Lozano’s career—historians, curators, and the keepers of her estate—this is worth dwelling upon. Obviously, there’s a parallel to be drawn between Lozano’s artworks and her copies versus her “private” notebooks. But what do we do with an artist whose intentions were ambiguous and, in the end, ambivalent at best? The published notebooks and the retrospectives offer one response, which seems more and more particular to the art world.

Lauren O’Neill-Butler is a New York–based writer and the managing editor of artforum.com. A frequent contributor to Artforum and to artforum.com, she has also written for Art Lies, bookforum.com, Paper Monument, and Time Out New York, in addition to exhibition catalogue essays for Milton Keynes Gallery, among others. She has taught at the Rhode Island School of Design and the School of Visual Arts.

- Helen Molesworth. “Tune In, Turn On, Drop Out: The Rejection of Lee Lozano,” Art Journal 61, no. 4 (Winter 2002): 70. ↩

- In addition to the laboratory notebooks, marked One through Three, Lozano made ten smaller notebooks, which were also numbered and labeled “private.” The artist occasionally revisited her notebooks and added new notes in the margins. In this review, all references to her own writings are derived from the laboratory notebooks. Lozano wrote only in capital letters in all of her notebooks, so quotations here are set in uppercase. ↩

- Alejandro Cesarco, ed., A Selection of Snapshots Taken by Felix Gonzalez-Torres (New York: A.R.T. Press, 2010). ↩

- Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner, “Sex in Public,” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 2 (Winter 1998): 547–66. ↩

- Lippard quoted in Lee Lozano, ed. Iris Müller-Westermann, exh. cat. (Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 2010), 194. ↩

- Piece reads: “when you’re ‘trying to make it’ keep going for years a pile of show announcements, press release material, all printed matter relating to the art scene. everything that comes in the mail or is accumulated other ways is tossed on the pile. when you ‘start to make it’ throw your own printed matter on the pile. let it be covered up by time the way everybody else’s is. companion piece: toss your own printed matter on top of the pile and keep it on top of the pile.” ↩

- Of this protest, Lippard has written, “The ‘anonymous’ core group faked a Whitney press release stating that there would be fifty percent women (and fifty percent of them ‘non-white’) in the show, then forged invitations to the opening and set up a generator and projector to show women’s slides on the outside walls of the museum while a sit-in was staged inside. The FBI came in search of the culprits.” Lippard, “Escape Attempts,” in Reconsidering the Object of Art: 1965–1975, ed. Ann Goldstein and Anne Rorimer, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 23. The critic Grace Glueck covered the protest for the New York Times, writing, “The protesters-in-chief (artists Poppy Johnson, Brenda Miller, Faith Ringgold; the critic Lucy Lippard) charge in a letter to the museum that, though it was founded by a woman, its record has been ‘lousy’ with regard to the exhibition and encouragement of the work of women artists.” Glueck, “Art Notes: At the Whitney, It’s Guerrilla Warfare,” New York Times, November 1, 1970, C20. ↩

- Lozano offered the following statement to a publication commemorating the Art Workers Coalition meeting, held April 10, 1969, at the School of Visual Arts: “for me there can be no art revolution that is separate from a science revolution, a political revolution, an education revolution, a drug revolution, a sex revolution, or a personal revolution. i cannot consider a program of museum reforms without equal attention to gallery reforms and art magazine reforms which would aim to eliminate stables of artists and writers. i will not call myself an art worker but rather an art dreamer and i will participate only in a total revolution simultaneously personal and public.” Art Workers Coalition, An Open Hearing on the Subject: What Should Be the Program of the Art Workers regarding Museum Reform and to Establish the Program of an Open Art Workers Coalition (New York: Art Workers Coalition, 1970), 38. ↩

- Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (New York: Praeger, 1973). ↩

- Todd Alden, “The Cave Paintings Exist Because the Caves Were Toilets: Reactivating the Work of Lee Lozano,” in Lee Lozano: Win First Don’t Last/Win Last Don’t Care, ed. Adam Szymczyk, exh. cat. (Basel: Schwabe, 2006), 16. ↩

- David Rieff, preface to Susan Sontag, Reborn: Journals and Notebooks, 1947–1963, ed. Rieff (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2008), vii and viii. ↩