This is the second essay the College Art Association has published entitled “Art Journal at Fifty.” The first, by CAA president Ruth Weisberg, was published in the magazine in the winter of 1991. The present essay is partly about how Art Journal came to have two fiftieth anniversaries, since neither of the titles is wrong—nor exactly right. Weisberg begins counting from 1941 with the founding of College Art Journal; I begin, at least in my title, in late 1960, when the word College is finally dropped; there is even a good case for beginning with 1929. An interesting history, I hope, lies in Art Journal’s multiple beginnings and refashionings. To tell that story, let me begin with yet a third fiftieth-anniversary essay, one written by the eminent medieval art historian and chairman emeritus of The Art Bulletin’s editorial committee in the spring of 1964: Milliard Meiss’s “The Art Bulletin at Fifty.” Meiss celebrated not just the golden anniversary of what was, by then, “one of the oldest journals in the history of art in the world,” and a “solid” and successful one, but also its financial security: the first third of the essay is devoted to a gift of $150,000 over five years from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation. Indeed, for an art historian who wrote movingly on Florentine art in the time of the Black Death, the essay is rather flatfootedly nuts and bolts; another third is devoted to the editorial structure of The Art Bulletin and a narrative history of the make-up of its editorial board and of its rotating editors.

Meiss’s essay was published in the March 1964 Art Bulletin, for obvious reasons, but it appeared in the Spring number of Art Journal, as well. As Meiss described the origin and the mission of the younger magazine, that was where the anniversary essay belonged. “During the first years after its appearance in 1913 the Art Bulletin served as an indispensible house organ for the newest branch of the humanities then beginning to grow against heavy resistance in our colleges and universities. Like a good cookbook, it was full of recipes for courses, most of them novel, to be offered to unsuspecting undergraduates, and for books to be placed in college libraries. This important function of the bulletin of the College Art Association (note the terminology) was later assumed by Parnassus and then, beginning in 1941, at a much more sophisticated and often theoretical level by the Bulletin’s companion, the Art Journal.”1 Insofar as it was now the real bulletin of CAA, its newsletter, Art Journal is where news of the Kress and discussions of the association’s internal affairs belonged.

As Meiss presented it, and as Meiss’s teacher and mentor Erwin Panofsky more familiarly described it a decade earlier, again in the pages of Art Journal—or to be more precise, in the pages of what was then called College Art Journal—The Art Bulletin is a magazine with a mission, a clear audience and editorial mandate. Panofsky wrote of The Art Bulletin as though it were synonymous with art history as a discipline: “At the beginning, the new discipline had to fight its way out of an entanglement with practical art instruction, art appreciation, and that amorphous monster ‘general education.’ The early issues of the Art Bulletin, founded in 1913 and now recognized as the leading art historical periodical of the world, were chiefly devoted to such topics as ‘What Instruction in Art Should the College A.B. Course Offer to the Future Layman?’; ‘The Value of Art in a College Course’; ‘What People Enjoy in Pictures’; or ‘Preparation of the Child for a College Course in Art.’”2 This is the “cookbook” Meiss described and, in his way, understood; Panofsky is less forgiving. “Art history, as we know it, sneaked in by the back door, under the guise of classical archaeology . . . evaluation of contemporary phenomena . . . and, characteristically, book reviews. . . . But in 1923, when the Art Bulletin carried ten unashamedly art historical articles and only one on art appreciation, and when it was found necessary to launch a competing periodical, the short-lived Art Studies, the battle was won . . .”3

The competing journal Panofsky refers to is not College Art Journal or its predecessor, Parnassus—the “companions” Meiss cites—but a journal of art history “edited by members of the departments of the Fine Arts at Harvard and Princeton universities,” an editorial tagline that suggests (even as it escapes) the complex divisions that have characterized the College Art Association from the beginning. The association’s divisions are both disciplinary and geographical—not only the still-obvious division between art history and art practice, but also the historical differences of class and geography that structured the American university between Ivy League schools and the eastern liberal-arts colleges and research universities established in their image on the one hand, and the state and land-grant colleges of the Midwest, South, and West on the other. In Art Studies and certainly in The Art Bulletin, art history as an autonomous discipline is secured in the image of a journal about nothing else, a journal that gains its identity by abjecting the other, banishing not only material practice—“practical art instruction”—but also any discussion of the pragmatics of art and art history in the classroom.

Among the things Panofsky is rather scathing about, as he patiently explains what he knows to the American readers of College Art Journal, are the “departmental system” (as opposed to the German “chair system”) and the American classroom, with its students “tested and graded without cease” and its young instructors and assistant professors “burdened with an excessive ‘teaching load’—a disgusting expression which in itself is a telling symptom . . .”4 The Art Bulletin in Panofsky’s presentation belongs to the discipline, constitutes it and polices its borders; Art Journal and the predecessors Meiss mentions, and to which I will return, belong to the department (the worldly bureaucratic manifestation of the idealist discipline) and to the classroom. Art Journal—like its predecessors—has been and in some sense still is a compromise: a compromise for, if not between, the major tensions within CAA itself, between studio practitioners and art historians and art educators.

The Spring 1964 issue of Art Journal, the issue in which Meiss’s birthday essay appears, contains a number of articles on modern and even contemporary topics, although in an odd sense it is not engaged with them, as though they were being written about from a distance—that distance we characterize, for better or worse, as academic: Edward T. Kelly of Marymount College in Tarrytown-on-Hudson offers a critique of Pop art, Alfred Werner rediscovers Max Liebermann, and Carl Belz writes on Man Ray and New York Dada. This is in a sense what Art Journal would become, a journal of nineteenth- and twentieth-century art, though only in the last decade has it declared itself to be one, in an editorial statement that first appeared on the masthead without fanfare in 2003. Following those articles and another, by J. P. Hodin, on “on the problematic nature of Jewish art”5 come the “College Museum Notes,” noting new acquisitions, recent exhibitions, and personnel changes; program notes for CAA’s annual conference; and “College Art News” of new programs and new buildings and new hires. On the second-last page, following a long brace of book reviews and a list of books received, there is an ad for CAA touting, among the perks of membership: “The Art Bulletin (in its 46th vol.). An illustrated quarterly devoted to scholarly articles on all periods of the history of art,” and “The Art Journal (in its 23rd vol.). An illustrated quarterly dealing primarily with problems of teaching art; contains articles on fundamental questions in education and is a forum for open discussion, news of the art world, etc.” It is all there, perhaps, in the difference between “devoted to” and “dealing with” and the “etc.” at the end.

Much is held in that “etc.,” and I will return to it, but let me turn for the moment to Meiss’s brief prehistory, to Parnassus, which published from 1929 until 1941, and was in many ways not the cookbook the early Art Bulletin had been or was accused of being.6 At least early on, it had a quite specific mission: it was, according to a membership solicitation in its inaugural issue in January 1929, “a quarterly of news and topical value devoted largely to art activities in Europe and edited by authorities in the field.” Through the first few years, it featured letters from editors in Rome, Berlin, London, Austria, the Soviet Union, and Spain, and abstracts from recent international periodicals—Belvedere, The Burlington Magazine, Pantheon, Pinacotheca, La Rivista d’Arte—and only a handful, if that, of articles devoted to the college campus or to anything outside the campus museum. Despite the focus on Europe, and to a certain extent written within that focus, Parnassus was a very local magazine; its view was that from CAA’s offices on Washington Square. It ran auction results, a New York exhibitions calendar, and a review of “art activities” in New York in its second number. Ten issues later, when it began to survey art activities nationally, its title was telling: the May 1930 issue featured both “A Perspective View of the New York Season,” by Audrey McMahon, and “A Cursive Review of Recent Museum Activities and Exhibitions outside New York,” by Irene Weir.

Perhaps this local flavor appears only in retrospect, but from its review of the new Museum of Modern Art, which opened in the Hecksher Building in 1929, to its presentation of the new building of the New School for Social Research, reviewing Joseph Urban’s building and murals by Thomas Hart Benton and José Clemente Orozco, the magazine seems quite specifically about the interests and “activities” of art in New York. But what most strongly drives home the specific and historical ties of the magazine to New York—and its ties to CAA as a particularly located institution in the 1930s—is its response to the Depression, and the American turn it takes after 1932, and the publication of Holger Cahill’s “Folk Art: Its Place in the American Tradition.” Cahill was then a curator at the new Museum of Modern Art and had organized the exhibition American Folk Art: Art of the Common Man 1750–1900. In both the exhibition and in the pages of Parnassus he insisted on the link between folk art and the modern tradition: “Folk art gives modern art an ancestry in the American tradition. . . . A fuller understanding of it will give us a perspective of American art history and a firmer belief in the enduring vitality of the American tradition.”7

Cahill would go on to direct the WPA Federal Arts Project in Washington, DC, but even closer to Parnassus, the FAP’s New York branch was run from the CAA offices by its New York regional director, Audrey McMahon, also CAA’s managing editor; Forbes Watson, technical director of the Public Works of Art Project, was a contributing editor. In a series of articles published between 1933 and 1937, McMahon, Watson, and others make clear CAA’s ties to the New Deal—or at least the historical proximity of the Depression and its political and social organizations and consequences. From proclamations such as McMahon’s “May the Artist Live?” to Watson’s “The USA Challenges the Artists,” to their surveys of programs and expenditures—McMahon’s “The Trend of the Government in Art” to Watson’s “Art and the Government in 1934”—and beyond, Parnassus’s focus doesn’t necessarily become less New York–centric, but, like much Depression-decade art and politics, turns inward. It begins to deal quite specifically with living artists and (to take the title of a CAA annual conference panel printed in Parnassus) with the “Place of the Artist in the Community.”8

As American art becomes an issue for Parnassus, the magazine’s national focus becomes somewhat less “cursive”; in May 1933 it publishes “An American Art from the College Campus: The Year’s Activities in the Nation’s Art Departments,” a survey that includes schools from Texas Tech and Southwest Missouri State to Beloit, Harvard, and Yale, accompanied by a listing of “Fine Arts Courses Offered by American Colleges, 1933–34,” which includes, as though in a nod to an earlier focus of Parnassus, a course entitled “Cultural Backgrounds for European Travel,” offered at the University of Southern California, along with “Pre-Dental Drawing.”9 The April 1937 issue is devoted to a national view not of campuses but of artists “worth knowing better,” with articles focused on the Far West, the Midwest, the East, and Colorado. There is by comparison, no mention of the Depression in The Art Bulletin until 1937, and then only as a chronological marker in Wallace Spencer Baldinger’s survey “Formal Change in Recent American Painting.”10 Baldinger was a professor of art history at the University of Oregon and the director of its museum, and his essay was one of only two on American art to appear in The Art Bulletin between 1923, Panofsky’s annus mirabilus, and the end of the 1930s, with Donald MacRae’s “Emerson and the Arts,” in 1938.11

In March 1937 Parnassus published Watson’s “Realism Undefeated,” a review of sorts of the new Whitney Museum’s exhibition New York Realists. But it was also, quite clearly, a manifesto designed to build a specifically American history of realism and an American bent toward it—and against Europe, or at least European art as it had arrived on these shores, drawn by the “countless thousands of American dollars [that] have pursued French Salon pictures, English portraits, and ancient arts from every land . . .” Despite the pictures that fill our collections, despite the “Modern Museum’s attempt to revive Dadaism” (a nod to the Museum of Modern Art’s Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism” which ran through January 1937), and, indeed, despite Parnassus’s earlier focus on Europe, Watson insists that Americans “have kept firmly grasped in our right hand a palm for realism. However we may waver in the strong breezes of the market place, it is on the brows of the realist that we place our palms of victory.”12 It is certainly where Parnassus placed its crown. In the mid-1930s, the cover of Parnassus had, at least briefly, born the banner “A Magazine of the Arts of All Centuries”; by the end of the decade it had become increasingly engaged in a specifically American contemporary art, and in October 1939 the editors announced “a series of twenty monographic articles on contemporary American artists.” “A poll of the entire country will be taken to determine the choice of artists.” The series didn’t, in the end, reach twenty, but those Parnassus did profile over the next year could easily have been assembled from the Whitney’s collections: Julian Levi, Richmond Barthe, Aaron Bohrod, Henry Varnum Poor, Fletcher Martin, Karl Zerbe, and Hobson Pittman. They were all realists and all regionalists.

While the series confirmed a shift in focus, the earlier profiles were surrounded by news, notes, and articles mostly on or spurred by recent museum shows and acquisitions, and, thus, by a remarkably global group of artworks. This hodgepodge of relatively short pieces on a heterogeneous array of objects had characterized the magazine since the early 1930s (and, in a sense, resists my attempt to pull a thread through the issues), and it would, at moments, come to characterize College Art Journal and Art Journal. Sharing the January 1940 table of contents with the American Julian Levi were articles on “Some Pre-Columbian Gold Pieces,” “Nicaraguan Pottery Designs by David Segueira,” and, remarkably early but noncommittally, “Television and the Arts”: “Only by learning from both brilliant failures and vulgar successes shall we discover the powers of television, and how we may use them for mass education in the arts.”13 As prescient as Nancy Newhall’s essay is, even more timely is Trevor Thomas’s “Artists, Africans, and Installation,” a critique of museum exhibitions of African arts: Thomas singled out MoMA and its 1939 Picasso retrospective in particular. Long before the arguments that emerged around William Rubins’s 1984 exhibition “Primitivism” and 20th-Century Art, Thomas, a curator of ethnology at the Liverpool Public Museum, insisted on the “highly essential need to submit concepts of primitive art to constant re-valuation,” and even more, to be wary of the concept itself, and the “unguarded employment” and “unconsidered use of the word primitive in contemporary criticism” and in the museum.14

The context for Fletcher Martin, the sixth of Parnassus’s contemporary American artists, was significantly different, and it marked the emergence of what the editor termed “The New Parnassus.” Lester Longman, a Princeton-trained art historian and the head of the art department at the University of Iowa, would be one of the strongest voices in the 1940s and 1950s for educating artists in the university and for the MFA degree, and that project certainly informed his vision of the new magazine. “No longer a heterogeneous series of papers on various phases of art history, Parnassus will henceforth endeavor to become an educational magazine fighting for good art, good scholarship, and good teaching. It will present short articles on live issues . . . timely and controversial problems in art history and criticism, and on esthetics and art theory. There will be short articles on modern art movements and contemporary artists, on art education (with special reference to colleges, universities, and art schools), on college art departments, and on exceptionally talented art students.”15 It is this last list that characterized Longman’s first issue. Martin shared the issue with profiles of the art department at the University of Chicago and Don Anderson, a “talented art student” from the University of Iowa, and with a broader essay by Stephen C. Pepper of the University of California at Berkeley, laying out a program for studio art in the university, illustrated with work by students of Erle Loran, Worth Ryder, and others.

Longman sought to differentiate his Parnassus from its earlier incarnation and, in a second editorial, worked to separate the art he would champion not only—and again—from European modernism, but also from the version of “American scene” painting that Watson and McMahon had championed. While we “are fast leaving behind the style of the first third of the twentieth century”—that is, the “radical” abstraction of the European avant-garde—the real “danger ahead for American art” is the “‘sanity in art’ movements [that] are more harmful now than any insanity movements of which the last generation may have been guilty,” that, indeed, amount to propaganda and the “principles of Berlin, disguised as native American.” The problem is “illustration . . . —sentimental, popular, photographic, propagandistic drivel, glorifying sunsets, forests, naked Aryans, big families, popular heroes, homely scenes, and anything else but genuine esthetic values,” and Longman singles out Thomas Hart Benton, a painter “who has long capitalized on the trend to subject appeal,” decrying not so much his painting (which “has improved”), as his apologists, his “trumpeters.”16 Whatever aesthetic or political distance Longman intends to open up between his Parnassus and the older one, the artists he embraces in the editorial’s closing paragraph, Bohrod and Alexander Brook, fall well within the juste milieu of the earlier Parnassus.

Longman’s inaugural edition of Parnassus was met in the following issue with two pages of laudatory letters, from museum directors and faculty at seventeen different colleges and universities from Acadia and Duke, to Johns Hopkins and Yale, as well as notes from Bohrod and Stuart Davis. Among the enthusiastic respondents were only two detractors, a representative of the American Antiquarian Society and Meyer Schapiro from Columbia. Schapiro’s critique was the more pointed: “Parnassus once looked like a dealer’s organ, now it seems to be a student’s monthly. I feel too much the atmosphere of the college art class . . . with its immature taste, its concern with teachers, courses, star students and prizes.”17 While there was no star student in Longman’s second issue, there were profiles of the art departments at Oberlin, Georgia, and the University of Chicago, and a survey entitled “Practice Courses in College Art Departments.” In December 1940, perhaps in response to Schapiro—or maybe to Panofsky and The Art Bulletin— Longman offered his views “on the uses of art history” in the college and university, particularly in relation to studio programs. Assuming that art historians would increasingly find themselves in colleges and universities with working artists, Longman argued against art history’s specialization and insularity, and called explicitly for the art historian as critic, theoretically engaged with the present. “We can no longer countenance the narrow specialization which relieves the art historian from the duty to examine the contribution of recent psychology, philosophy, sociology, anthropology, and political, economic, and literary history. The need of the day is rather for breadth of interpretation than intense exploration of detail.”18

That issue featured another, rather different attempt to upset CAA’s academic hierarchy and unseat art history: a roundtable in print entitled “Why Give a Ph.D. in Creative Art?” comprising a statement by Ralph Fanning of Ohio State and short responses by Pepper of the University of California at Berkeley and Millard Sheets from Pomona, and, in the following issue, Norman Rice from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and G. Haydn Huntley from the University of Chicago.19 Despite the fact that most of these educators wrote against the PhD, the presence of their discussion along with Longman’s critique of art history and his focus on the teaching of art in the college and university clearly positioned Parnassus as The Art Bulletin’s opposite—and clearly reflected the divisions within CAA. By the early 1940s, The Art Bulletin was an explicitly peer-reviewed journal and had become even more insistently professional; Longman’s equation seems to have been that if The Art Bulletin was art history’s dominant journal, then Parnassus should consciously assume the role of studio art’s magazine—or at least a journal geared to the teaching of studio art. Teaching and the subject of teaching art history disappeared from the pages of The Art Bulletin early on; they would appear on occasion in Parnassus and College Art Journal going forward, in early discussions of the use of color slides, for example, and later in discussions of the survey.

Perhaps because Longman made his position so clear and perhaps because of “budget limitations” and the decline in advertising that came when the magazine began to focus outside New York and beyond college gallery exhibitions, Parnassus ceased publication in May 1941. While CAA president Sumner Crosby’s letter announced the forthcoming creation of a College Art Journal that would “promote an understanding and tolerance among art teachers of all types,” “concentrate on such communications as pertain to the study and interpretation of art within the framework of academic instruction,” and “contain news and information about college art departments . . . useful to student and professor alike,” he also insisted—contra Longman—that “the Directors, after a careful review of the position of the Association in the field of art instruction, believe that its primary function is the support and promotion of the teaching of the history, analysis, and interpretation, rather than the creation of art.”20 Crosby’s letter was accompanied by a number of others—all of them decrying the demise of Parnassus. Pepper of UC Berkeley wrote that he “fully realize[d] the full implication of the resolution”: it meant the re-eruption of the “old issue” of “history of art versus practice—appreciation—aesthetic theory—and criticism. . . . I do not think the Board can realize how strongly college art teachers all over the country will feel about the resolution. I do not think that the College Art Association as a mere History of Art Association will long have a great influence on the teaching of art in this country.” The letter from John Alford, an art historian and painter, and head of the art department at the University of Toronto, made public his resignation from the CAA’s board.21

Crosby wrote both the obituary for Parnassus and the editorial statement for the new quarterly College Art Journal, which, on the one hand, was imagined as a very different magazine than its predecessor: a smaller, leaner, and more insular magazine, something closer to the present CAA News than to Parnassus. “This new periodical . . . will function primarily as an organ of the College Art Association, rather than as a magazine in competition with other art periodicals. There will be no editorial biases.” At the same time, Crosby’s list of topics pertinent to members hews closely to the debates of Longman’s Parnassus: The magazine’s “purpose is also to provide information about innovations in education; to present theories and criticisms of the various methods involved in interpreting the art of the past and of the present; to announce opportunities and resources available for developing educational practices; and to promote, even to provoke, discussion of these and of other fundamental problems. There will also be reports of experimental courses and programs; of exhibitions of significant value to college art departments; of group or individual projects in research and in education; and finally there will be short reviews of those books which are of special value for undergraduate teaching.”22

The most obvious differences between College Art Journal and Longman’s Parnassus were physical: Parnassus began life in 1929 with a cut size of eleven by eight inches, but from 1934 until its demise it ran a bit larger, and always on coated stock. Fitting for its role as CAA’s newsletter, College Art Journal debuted at eight and a quarter by five and a quarter inches and was printed on inexpensive, uncoated paper. In contrast to the ads that ran in Parnassus—from the artists’ supplier Grumbacher and such galleries as Duveen, Wildenstein, and Knoedler (indeed, Duveen continued to advertise to the end despite Schapiro’s suggestion that Parnassus was no longer a “dealer’s organ”)—there were no ads in the new College Art Journal and, until 1945, no illustrations of any sort. When advertisements reappear in 1946, they are ads not for dealers, but for other art magazines—The Art Digest, Art Quarterly, Artibus Asiae—and book publishers; illustrations return that same year, first as line reproductions of graphic works by artists such as Henri Matisse, Paul Klee, Henry Moore, Oskar Kokoschka, and Max Beckmann. Halftone illustrations accompanying articles begin to appear regularly only after 1952.

Parnassus featured black-and-white cover photographs through 1935, and color covers sans images afterward. Again, College Art Journal was far more modest: throughout the 1940s, its covers bore only the journal’s name, in capital letters in simple serif type at the beginning, then in lower case in a somewhat heavier, rounder type. A few modest attempts at design and brand identity premiered in the 1940s and early 1950s: the first, which appeared on the magazine’s cover in May 1946, and on the inside through 1949, was something of a printer’s chop or dingbat that combined the magazine’s initials, turning the C and the curved end of the J into tight spirals. While the first design pushed College Art Journal’s initials together, the second, which appeared from Winter 1951–52 through Spring 1954, separated them into the far corners of the page. Two lines, a thin vertical and a thicker horizontal one, form a cross that segments the cover surface into four areas; each letter, in thin serif type, is isolated in its own quadrant. The fourth area bears the issue number and date. College Art Journal’s first cover image appears in Summer 1954, with a half-tone photograph of a work by the sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, but the next issue returned to the segmented cover. Cover images, first line art (a burst by Adolph Gottlieb) and then halftones (of a drawing by David Smith), begin to appear regularly in Winter 1955.

The presence of Gottlieb and Smith on College Art Journal’s cover attests to another difference between it and its predecessor: the new magazine’s relative openness to modern art. The first issue of College Art Journal featured another article on the possibilities of television as “a new means of art education” and a call for the teaching of Latin American Art—a call we have perhaps yet to heed. But the lead essay in the first issue of College Art Journal was Alfred Barr, Jr.’s “Modern Art Makes History, Too,” his case for the study of modern art history: “Isn’t it true that our art historians as a whole still do not seem to be at home in the art of our own time?”23 One might think of Barr’s call and the journal’s turn toward a modern art history as historical in the large sense; outside the CAA offices as well as inside, there is a waning of the American Scene in the first years of the war and the arrival on American shores of a number of Europe’s most important artists. But CAJ’s claim to modern art might also have been a parochial one, as well: part of the ongoing task of defining its identity in relation to The Art Bulletin. As Barr himself noted, the modern was an area in which The Art Bulletin had only begun to publish: “Up to a decade ago, so far as I can recall, the learned magazines such as The Art Bulletin and Art Studies published between them only one article on modern art and that was hostile. But this year, under enlightened editorship, The Art Bulletin has published articles on post-first-World-War German art, on Seurat’s style, on Picasso’s ‘negro’ period.”24

College Art Journal published Barr’s writings with some frequency in the 1940s and 1950s; when in the closing months of World War II he issued a second challenge to art historians, to “interest themselves more deeply in studying the history of the arts in the United States,” Barr again pointed to the paucity of such an interest on the part of The Art Bulletin: “Since 1918 the Art Bulletin has published about 150 articles on Early Christian and Medieval art, 165 on the Renaissance and Modern art of Europe but only seven really scholarly articles in the American field—and of these, six were on architecture, only one on painting.”25

Barr’s insistence in CAJ’s first issue on the importance of modern art for the generalist undergraduate and on the “obvious and urgent” need for “graduate work in modern art,” touched off a discussion that extended over four numbers, with comments by Frank Jewett Mather, Robert Goldwater, and James Thrall Soby.26 John Alford took up the discussion again in 1944, in a review of André Masson’s Anatomy of My Universe that focused on what it might mean to teach about Masson, and to whom: “M. Masson’s art is already an intellectual and emotional protest. . . . In so far as his reactions . . . are symptomatic of a cultural condition of social kind they deserve serious analytical attention over and beyond their achievement of imaginative realization; but . . . not by freshman.”27

The sense that modern art was both literate and difficult—that it was worthy college material—was clear from a short-lived series entitled “Contemporary Documents,” begun in 1949, which featured writings by artists such as Beckmann, Ben Shahn, George L. K. Morris, Isamu Noguchi, and Georg Grosz. (The series would continue with statements and printed addresses by Gottlieb, Smith, and others, without the series title, throughout the 1950s, and revived, somewhat differently, by Lenore Malen and Buzz Spector in the early 1990s, with a series of “Artists’ Writings” and, by 1992, as “Artists’ Pages.”) The artist College Art Journal imagined was in some sense the articulate American artist of Abstract Expressionism, the artist Ad Reinhardt lampooned in the CAJ in 1954 as “the artist-professor and traveling-design-salesman, the Art-Digest-philosopher-poet and Bauhaus-exerciser, the avant-garde-huckster-handicraftsman and educational-shop-keeper, the holy-roller-explainer-entertainer-in residence.”28

But the contributors to CAJ and to the arts on campus were indeed smart and quite philosophical artists: see, for example, Stanton MacDonald Wright’s program for a textbook on Chinese art, Sidney Tillim’s critical appreciation of Jackson Pollock, Jean Charlot’s remembrance of Orozco (by far the most popular artist in CAJ), Leon Golub’s “Critique of Abstract Expressionism,” or Mark Tobey on the “Japanese Tradition in Modern Art.”29 In addition to those artists, there were committed art educators as well, many closer to Reinhardt’s “Bauhaus-exercisers,” perhaps, than to his “philosopher-poets,” but writers nonetheless: see Edward Rannells’s “Theory of Requiredness in the Understanding of Art,” a strongly Gestalt reading by an artist-educator from the University of Kentucky, or the Bauhaus-trained Ernest Mundt, of the California School of Fine Arts, on “Scientific and Artistic Knowledge in Art Education.”30 These, along with essays like the American surrealist Walter Quirt’s “Art’s Theoretical Basis” and Thomas Munro’s multiple essays on psychological aesthetics and the venues of art education, might be what Meiss had in mind when he spoke of CAJ as a more sophisticated and theoretical cookbook than the earliest Art Bulletin had been.31

Still, most of the sustained discussion in CAJ in the 1940s and well into the 1950s concerned the place(s) of art on the university campus; not the profiles of specific classrooms and departments featured in the old Parnassus, but essays on how art—both history and practice—might fit within the scope and the goals of the broader university. In March 1944, the magazine published a committee “Statement on the Place of the History of Art in the Liberal Arts Curriculum,” followed in November of that year by a second committee “Statement on the Practice of Art Courses.”32 In 1946 a third committee weighed in on “The Practice of Art in a Liberal Education”; the question of how or whether art—particularly studio-art practice—fits within a broad liberal-arts or “general” education was a topic of continuing interest, not just for CAA committees but for any number of individual authors.

Across the 1940s the titles are remarkably similar: “Art in Liberal Education,” “The Fine Arts in Liberal Education,” “The Graphic Arts in Liberal Education,” “The Study of Architecture in the Liberal Arts College,” “Art and General Education,” or “Art, Artists, and General Education.” The last title in this abbreviated list dates from 1954, and it suggests another, somewhat different emphasis: if the first essays aimed at securing art’s place on the liberal-arts campus, a second group, which also begins in the 1940s but grows in prominence in the 1950s, seeks to secure the artist’s place there, and in the broader university, whether as teacher or as student. Its opening salvo is Longman’s 1945 symposium in print, “Why Not Educate Artists in Colleges?” with responses by William Gropper, Zoltan Sepeshy, Albert Barnes, and Otto Brendel.33 Do artists belong on campus? Do they benefit from being there, as artists or as human beings? Are colleges and universities capable of training them? These are the questions posed by essays such as “The Artist and the Liberal Arts,” “The Intramural Artist,” “General Education for Art Students,” and “A Psychologist’s View of General Education for the Artist.”34

Undergraduate artists necessarily pose the question of graduate education, and in the 1960s, the issue of the PhD in studio. The papers gathered together for “The Ph.D. for the Creative Artist,” by Allen S. Weller, Manuel Barkan, F. Louis Hoover, and Kenneth E. Hudson, were originally delivered at the Midwest College Art Conference at the University of Wisconsin in October 1959, where, in its final session, the conference recommended “the MFA or equivalent degree be considered the terminal degree for teachers of studio courses,” to which it added, “The Conference deplores the tendency which has developed in some institutions of higher learning to assume that the Ph.D. is an equally valid degree in all disciplines.”35 The topic was, as we have seen, raised briefly and shelved by contributors to Parnassus in 1940, and the discussion has returned quite vigorously in our present moment. While most of the debate is taking place outside today’s Art Journal, it’s worth noting that the only recent AJ essay addressing the studio PhD (and one of the few in today’s AJ addressing aspects of education)—“The Studio-Art Doctorate in America,” by Timothy Emlyn Jones—stands in favor of it and argues its inevitability.36

The college classroom and the educational museum framed in one way or another almost all of the discussions in College Art Journal, and when in fall 1960 the journal dropped “college” from its title, to “more appropriately indicate the scope of this publication,” the first cover, of a Thai bronze of the Bodhisattva, accompanied an article on Thai art in American college museums. An editorial note observed, “American universities and museums have shown increasing interest in Oriental Art, especially since the war. Now we are to see for the first time a major exhibition of the Art of Thailand,” an exhibition organized by Indiana University.37 (From the time images first appeared on CAJ’s cover in 1955 well into the 1960s, many covers, perhaps even a majority, featured non-Western art, often in conjunction with articles on or notices from college and university museums. Images from these institutions also comprise a third class of covers: drawings and plans for the new campus art centers and galleries that spring up throughout the 1950s.) The brief editor’s note on the journal’s name change also highlighted another change: Art Journal’s larger size, which it described as “more flexible, attractive, and economical.” There was no discussion of content, and in many ways that editorial silence—and the magazine’s relatively mixed and pragmatic approach—did not change. In addition to the note on the Arts of Thailand exhibition, the issue featured essays on art in the Roosevelt era, on Baroque painting in Germany and Austria, on John Dewey’s materialism, and on courses in art at the Air Force Academy.

Art Journal’s first editorial statement doesn’t come until 1980, long after the 1973 retirement of Henry Hope and the arrival of Diane Kelder as the magazine’s first new editor since the 1940s. Hope, like Parnassus’s Longman, was an Ivy League–trained art historian in charge of one of the Big Ten fine arts departments central to the proliferation of the MFA in the1950s; he was chair of fine arts at Indiana University from 1941 to 1967 and editor of Art Journal from 1944 to 1973. One of Kelder’s missions, after so many years of the journal under the same hand, was “to have the journal concentrate more specifically on nineteenth- and twentieth-century art.”38 While her first issue, Fall 1973, contained no statement of the journal’s new direction, her attempts to give it a greater concentration on the modern period was indeed suggested by the table of contents. The issue included essays on Thomas Anshutz, Beckmann, and Max Ernst, and two essays on tribal arts, on Baule figure sculpture and Sepik sculpture from New Guinea. Her editorial mandate would become even clearer over subsequent issues in the 1970s, as would the sense of Art Journal as an academic journal rather than a bulletin, with the creation of CAA Newsletter in 1976, and the departure of at least some of the journal’s “news and notes.” Her Art Journal also increasingly recorded the social and cultural transformations of the decade as they affected art and art history, in issues devoted to artists’ rights—with articles on the “National Art Workers’ Community” and “The Role of the Artist in Today’s Society” (a roundtable that featured Carl Andre, Hans Haacke, John Perreault, and Cindy Nemser)—and feminist art history—with contributions by Lucy Lippard, Mary Garrard, Josephine Withers, and others.

Art Journal’s first “statement of purpose” appeared some twenty years after its name, in Spring 1980. The journal, with new type and design by Dean Morris and the Cooper Union Center for Design and Typography, was to be “a journal of ideas and opinions,” focusing “on critical and aesthetic issues in the visual arts of our time.”39 In many ways this is the mission to which Art Journal continues to aspire. The crux of the short statement, though, was not so much a question of mission as of format: the new Art Journal would be thematic, with each issue devoted to a single topic and edited by a guest editor chosen, for the next decade, by a small editorial board that initially included Anne Coffin Hanson, Ellen Lanyon, George Sadek, and Irving Sandler—a board significantly closer to contemporary issues in art and art history than the journal’s earlier editors had been.

The first theme issue, edited by Donald Saff, an artist and printmaker with the workshop Graphicstudio, was devoted to printmaking as a collaborative art, with contributions by Jim Dine, Garo Antresian of Tamarind, and Kathan Brown of Crown Point Press. Subsequent theme issues in the 1980s were somewhat less engaged with questions specific to studio practice, but contemporary art practice was addressed in issues devoted to artists’ writings (with contributions by Daniel Buren, Iain Baxter, Howardena Pindell, Lawrence Weiner, and others), performance, and video.

Most of the issues engaged with questions of theory and method raised by the “new art history” and its—and the social history of art’s—focus on nineteenth-century art and the early twentieth-century avant-gardes. Issues were devoted to Manet, Cubism, Futurism, and the Russian avant-garde—with, among other things, a testy response from Donald Judd: “It bothers me that this interest [in Russian art] is so late, too late to allow them to do a lot rather than a little, and late because they are dead. . . . In the thirty-sixth year of the American Empire, the public is not so different from the Russian public that ignored those artists.”40 Linda Nochlin guest-edited an issue entitled “The Political Unconscious in Nineteenth-Century Art,” and Patricia Mainardi followed with one on “Nineteenth-Century French Art Institutions.” An issue guest-edited by Alan Trachtenberg, focusing on photography’s challenges to criticism and art history, featured Allan Sekula’s now-canonical “The Traffic in Photographs,” and Henri Zerner’s issue, “The Crisis in the Discipline,” addressed both the intellectual and institutional roots of art history (Joan Hart) and its current intellectual, philosophical, and ideological pitfalls (essays by David Summers, O. K. Werckmeister, and Donald Preziosi).

Selecting issue editors from member proposals, rounding up texts, and producing four guest-edited Art Journals a year was not easy: deadlines were missed, quality varied, and there were no issues published at all in 1986. In 1989, in response to these problems and to a report on CAA’s publications prepared by Susan Rossen, executive director of publications at the Art Institute of Chicago, CAA appointed its first publications manager, Virginia Wageman, and Art Journal was given an executive editor to work with the editorial board and individual issue guest editors.41 Lenore Malen, Art Journal’s first executive editor, was also its first and, thus far, only artist editor. A New York–based artist working in a variety of media, an independent curator, and a writer whose work had appeared in Arts Magazine, Art in America, and Artnews, Malen, with the editorial board, reintroduced artists’ writings as a regular feature of the magazine; in the first year, the artist and writer Buzz Spector served as “Artists’ Writings Editor.” In 1992, the “Artists’ Writings” section was renamed “Artist’s Pages,” and its mission expanded to include original works created especially for the magazine. Among the artists to write or make new work for Art Journal during Malen’s tenure were Agnes Denes, Rackstraw Downes, Jimmy Durham, Mary Kelly, Joseph Kosuth, James Luna, Kay Rosen, and Mierle Laderman Ukeles.

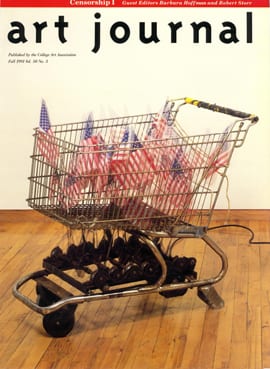

Guest-edited themed issues continued through Malen’s tenure (1990–96) and into the late 1990s, and a number of issues in that decade responded to the “culture wars” and questions of identity and sexuality current in much art practice: Robert Storr and Barbara Hoffman, CAA’s legal counsel, coedited two issues in 1991 on censorship; the first of those included the first publication of Robert Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio. Further issues were devoted to performance, feminist art history, the masculine ideal, and gay and lesbian presence in art and art history. The themes of the 1990s were in many cases more current—more engaged in art criticism and contemporary practice—than the art-historical issues of the 1980s, and, beginning with painter Curt Barnes’s issue on “Constructed Painting” (Spring 1991), a number were guest-edited by artists or by artists in collaboration with art critics or historians. The artist Luis Camnitzer and the art historian Shifra Goldman edited an issue devoted to contemporary Latin American Art (Winter 1992), and the painter Kay WalkingStick coedited an issue on recent Native American art with W. Jackson Rushing (Autumn 1992). An issue guest-edited by the art historian Debra Bricker Balken, entitled “Interactions between Artists and Writers,” was devoted to such collaborations (Winter 1993). The theme issues of the 1990s were not only more current—with issues devoted to genetics, ecology, and performance at the end of the twentieth century—they were also more eclectic, with strong and interesting issues devoted to the scatological (from ancient Mexico and the July Monarchy to Piero Manzoni and John Miller); to old age in the arts and the art world (edited by the painter Robert Berlind, with interviews and statements by Elizabeth Catlett, John Coplans, and Lamar Dodd, and others); and a strange one, edited by the artist Phil Simkin, devoted to the letter “C”—essays and artworks with titles ranging from “Cyberart Considerations” to “A Chance Convergence of Caravaggio’s Cohorts with the Cézanne Clan,” accompanied by Sarah Smith’s Borgesian “Gimel, K, and Q: Alphabetic Form and Purging the English Language” and Pat Oleszko’s ribald “Contrary Corp-o-Reality.”

Spring 1998 saw Art Journal’s last guest-edited thematic issue. Edited by Pamela Jones, a Renaissance art historian at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, it addressed Christian devotional art from Renaissance to the present. The theme is far from the contemporary focus of most of Art Journal’s issues in the 1990s—certainly it’s some distance from Martha Wilson’s examination of new performance, the issue that immediately preceded it—and even from the nineteenth- and twentieth-century focus of the 1980s and before. The Spring 1998 number had its beginnings—as indeed other theme issues had—in a panel at the CAA’s annual conference, but it’s not the resemblance to a conference panel that is odd, but the resemblance to The Art Bulletin; indeed Sally Promey’s strong and interesting contribution on John Singer Sargent’s Boston Public Library murals continues an essay she had published in The Art Bulletin a year earlier.42 While Jones’s issue was in no way the cause—and perhaps not even related—an editorial statement in the next issue asserted clearly for the first time that Art Journal’s mission was “to focus on topics related to twentieth- and twenty-first-century concerns” and to be “responsive to the issues of the moment in the arts, both nationally and internationally.”43

The editors noted the journal’s new design (which remains in most respects its current one) and announced the end of “strictly theme-based” and guest-edited issues. While subsequent issues were not themed throughout, the editorial voice has been strong over the past decade: Janet A. Kaplan, Art Journal’s executive editor at the time, and her successors—Patricia C. Phillips, Judith F. Rodenbeck, and now Katy Siegel—have featured thematic sections, or have paired and grouped essays; at their most effective, they curated a dialogue among the constituents the 1998 editorial statement lays out: “artists, art historians, and other writers in the arts.” That statement also worked to resituate Art Journal among other journals, asserting for the first time in print its scholarly commitment to peer review, and at the same time imagining its operating space as slightly outside the enclosures of academic publishing, as “between commercial publishing, academic presses, and artist presses.” The 1998 statement, crafted by an editorial board that included Alexandra Anderson-Spivy, Carol Becker, Michael Brenson, Johanna Drucker, David Joselit, Kaplan; incoming members Simon Leung, Joe Lewis, and Steve Nelson; and outgoing members Ursula van Rydingsvard, Judith Wilson, and Martha Wilson, continues to be the journal’s guiding mission statement, and since Fall 2003, it has appeared, only slightly condensed, in the masthead of each issue.

Howard Singerman is an Associate Professor of Contemporary Art and Art Theory at the University of Virginia and the Reviews Editor at Art Journal. A contributor to numerous exhibition catalogues for contemporary exhibitions nationally and internationally, his 1999 book, Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University, has become a landmark in the field. Singerman’s latest book, Art History, After Sherrie Levine, is forthcoming this spring from University of California Press.

- Millard Meiss, “The Art Bulletin at Fifty,” Art Journal 23, no. 3 (Spring 1964): 226. ↩

- Erwin Panofsky, “Three Decades of Art History in the United States: Impressions of a Transplanted European,” College Art Journal 14, no. 1 (Fall 1954): 10. ↩

- Ibid., 10. ↩

- Ibid., 21, 23. ↩

- J. P. Hodin, “The Visual Arts and Judaism,” Art Journal 23, no. 3 (Spring 1964): 222. ↩

- In some years, Parnassus published seven times, in others, eight. ↩

- Holger Cahill, “Folk Art: Its Place in the American Tradition,” Parnassus 4, no. 3 (March 1932): 4. ↩

- Audrey McMahon, “May the Artist Live? Parnassus 5, no. 5 (October 1933): 1-4; Forbes Watson, “The USA Challenges the Artists,” Parnassus 6, no. 1 (January, 1934): 1–2; McMahon, “The Trend of the Government in Art,” Parnassus 8, no. 1 (January 1936): 2–6; Watson, “Art and the Government,” Parnassus 6, no. 8 (January 1935): 12–16; Edward Alden Jewell, Alfons Goldschmidt, Jean Lurcat, and Gorham B. Munson, “The Place of the Artist in the Community,” Parnassus 6, no. 4 (April 1934): 1–4. ↩

- Hope Christie Skillman, “An American Art from the College Campus: The Year’s Activities in the Nation’s Art Departments,” Parnassus 5, no. 4 (May 1933): 27–34. ↩

- Wallace Spencer Baldinger, “Formal Change in Recent American Painting,” Art Bulletin 19, no. 4 (December 1937): 580–91. ↩

- Donald MacRae, “Emerson and the Arts,” Art Bulletin 20, no. 1 (March 1938): 78–95. ↩

- Forbes Watson, “Realism Undefeated,” Parnassus 9, no. 3 (March 1937): 11, 38, 11. ↩

- Nancy Newhall, “Television and the Arts,” Parnassus 12, no. 1 (January 1940): 38. ↩

- Trevor Thomas, “Artists, Africans, and Installation,” Parnassus 12, no. 1 (January 1940): 32–36. ↩

- Lester Longman, “The New Parnassus,” Parnassus 12, no. 6 (October 1940): 4. ↩

- Lester Longman, “Better American Art,” Parnassus 12, no. 6 (October 1940): 4–5. ↩

- Meyer Schapiro, letter to the editor, Parnassus 12, no. 7 (November 1940): 2. ↩

- Lester Longman, “On the Uses of Art History,” Parnassus 12, no. 8 (December 1940): 5; and Parnassus 13, no. 1 (January 1941): 2. ↩

- Ralph Fanning, “Why Give a Ph.D. in Creative Art?” Parnassus 12, no. 8 (December 1940): 2–3. ↩

- Sumner McK. Crosby, “To the Members of the College Art Association and Subscribers to Parnassus,” Parnassus 13, no. 5 (May 1941): 162. ↩

- “Forum: C.A.A. Policy Altered—Parnassus Abolished,” Parnassus 13, no. 4 (May 1941): 162. ↩

- Sumner McK. Crosby, “College Art Journal,” College Art Journal 1, no. 1 (November 1941): 2. This issue began the quarterly schedule of publication that has continued (with very few exceptions) to the present day. ↩

- Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Modern Art Makes History, Too,” College Art Journal 1, no. 1 (November 1941): 3. ↩

- Ibid., 4. ↩

- Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “The Study of American Art in Colleges: A Preface,” College Art Journal 4, no, 4 (May 1945): 179. ↩

- Barr, “Modern Art Makes History, Too,” 5. ↩

- John Alford, “The Universe of André Masson,” College Art Journal 3, no. 2 (January 1944): 44. ↩

- Ad Reinhardt, “The Artist in Search of an Academy. Part Two: Who Are the Artists?” College Art Journal 13, no. 4 (Summer 1954): 315. ↩

- S. MacDonald Wright, “Blueprint for a Textbook on Art,” College Art Journal 4, no. 3 (March 1945): 144–48; Sidney Tillim, “Jackson Pollock: A Critical Evaluation,” College Art Journal 16, no. 3 (Spring 1957): 242–43; Jean Charlot, “Orozco in New York: Based on His Letters to the Author,” College Art Journal 19, no. 1 (Fall 1959): 40–53; Leon Golub, “A Critique of Abstract Expressionism,” College Art Journal 14, no. 2 (Winter 1955): 142–47; Mark Tobey, “Japanese Traditions and American Art,” College Art Journal 18, no. 1 (Fall 1958): 20–24. ↩

- Edward W. Rannells, “The Theory of Requiredness in the Understanding of Art,” College Art Journal 5, no. 1 (November 1945): 15–17; Ernest Mundt, “Scientific and Artistic Knowledge in Art Education,” College Art Journal 10, no. 4 (Summer 1951): 333–36. ↩

- Walter Quirt, “Art’s Theoretical Basis,” College Art Journal 12, no. 1 (Fall 1952): 12–15; Thomas Munro, “The Place of Aesthetics in the Art Museum,” College Art Journal 6, no. 3 (Spring 1947): 173–88; Munro, “The Relation of Educational Programs in Museums to Colleges, Universities, and Technical Schools in the Community,” College Art Journal 8, no. 3 (Spring 1949): 190–95; Munro, “The Art Museum and Creative Originality,” College Art Journal 10, no. 3 (Spring 1951): 257–60; Munro, “The Criticism of Criticism: An Outline for Analysis Applicable to Criticism of Any Art,” College Art Journal 17, no. 2 (Winter 1958): 197–98. ↩

- Millard Meiss, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Sumner McK. Crosby, Sirarpie Der Nersessian, George Kubler, Rensselaer W. Lee, Ulrich Middeldorf, C. R. Morey, Erwin Panofsky, Stephen Pepper, Chandler R. Post, Agnes Rindge, Paul J. Sachs, Meyer Schapiro, and Clarence H. Ward, “A Statement on the Place of the History of Art in the Liberal Arts Curriculum by a Committee of the College Art Association,” College Art Journal 3, no. 3 (March 1944): 82–87; Peppino Mangravite, George Biddle, Jean Charlot, Bartlett H. Hayes, Jr., Daniel Catton Rich, Boardman Robinson, Edward W. Root, and Franklin C. Watkins, “A Statement on the Practice of Art Courses by a Committee of the College Art Association,” College Art Journal 4, no. 4 (November 1944): 33–38. ↩

- Lester D. Longman, “Why Not Educate Artists in Colleges?” College Art Journal 4, no. 3 (March 1945): 132–36. ↩

- Ralph L. Wickiser, “The Artist and the Liberal Arts,” College Art Journal 11, no. 3 (Spring 1952): 180–81; George Rickey, “The Intramural Artist,” College Art Journal 9, no. 4 (Summer 1950): 389–94; Kenneth E. Hudson, “General Education for Art Students,” College Art Journal 16, no. 2 (Winter 1957): 146–55; Rudolf Arnheim, “A Psychologist’s View of General Education for the Artist,” College Art Journal 8, no. 4 (Summer 1949): 268–71. ↩

- Allen S. Weller, Manuel Barkan, F. Louis Hoover, and Kenneth E. Hudson, “The Ph.D. for the Creative Artist,” College Art Journal 19, no. 4 (Summer 1960): 343–52. ↩

- Timothy Emlyn Jones, “The Studio-Art Doctorate in America,” Art Journal 65, no. 2 (Summer 2006): 124–27. ↩

- “Asia and America,” Art Journal 1, no. 1 (Fall 1960): 1. ↩

- Craig Houser, “The Changing Face of Scholarly Publishing: CAA’s Publications Program,” Chapter 5 in The Eye, the Hand, the Mind: 100 Years of the College Art Association, ed. Susan Ball (Piscataway: Rutgers University Press, 2010), 76. ↩

- “Statement of Purpose by the Art Journal Editorial Board” (Anne Coffin Hanson, Ellen Lanyon, George Sadek, and Irving Sandler; Rose R. Weil, managing editor), Art Journal 39, no. 3 (Spring 1980): 165. ↩

- George Rickey and Donald Judd, “Two Contemporary Artists Comment,” Art Journal 41, no. 3 (Fall 1981): 250. ↩

- Houser, 78. ↩

- Sally M. Promey, “The Afterlives of Sargent’s Prophets,” Art Journal 57, no. 1 (Spring 1998): 31–44. See also Promey, “Sargent’s Truncated Triumph: Art and Religion at the Boston Public Library, 1890–1925,” Art Bulletin 79, no. 2 (June 1997): 217–50. ↩

- “From the Editorial Board,” Art Journal 57, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 2–3. ↩