The following remarks are edited from an onsite interview and a public dialogue at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa on March 12, 2017. The exchanges were organized by the art historians Jaimey Hamilton Faris and Margo Machida to offer an opportunity for Hawaiʻi-born artists Sean Connelly and Lynne Yamamoto to discuss their new sculptural works for the inaugural Honolulu Biennial 2017, Middle of Now|Here (March 8–May 8, 2017). Both artists installed their work at the Foster Botanical Garden in Honolulu, on the island of Oʻahu.

Individually, Connelly and Yamamoto’s projects recognize the significance of locality and place in illuminating the enduring impact of entwined histories and shifting alignments among the native, local, and global. For both artists, Hawaiʻi’s built environment and material culture act as a solid anchor to register the islands’ Asian and Indigenous presences, and to gesture to the development of a local, hybrid vernacular architectural vocabulary. Their works take the form of architectonic structures variously inspired by Hawaiʻi’s plantation-style houses, 1920s bungalows, modern architecture, Native Hawaiian building methods, and construction techniques found throughout the Pacific.

The Botanical Garden, initiated in 1853, is in the verdant Nuʻuanu Valley, where the historic homes of Native Hawaiian royalty were once closely flanked by an immigrant neighborhood. Connelly and Yamamoto’s adjacent, site-specific works engage issues of place, history, migration, and environmentalism via intersections between Asian diasporas and Indigenous people and cultures in the Pacific. The artists’ commentaries interrogate the positions, critical strategies, geopolitical context, and materials that they selected to engage with the island’s geography and its multilayered histories. Whereas critical attention is often focused on continental geographies and geopolitics, transcultural artist projects like these shift attention to the Asia Pacific region, and to the significance of Pacific Islands as subjects and sites that delineate constellations of human relations, societal positions, and subjectivities with a transoceanic and planetary span.

Ultimately, both artists seek an active and conscious engagement with the history of land use and development in Hawaiʻi. Prior to European contact in the late-eighteenth century, Native Hawaiians developed the ahupuaʻa system in which the division of land and natural resources was integrally shaped by the island’s geography. Under this sustainable arrangement, the commoners’ cultivation of land, in conjunction with fishing, long provided food for themselves and for the aliʻi (the hereditary rulers). By the mid-nineteenth century investment by local American business interests in sugar and pineapple cash crops began, leading to the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy and annexation of Hawaiʻi by the United States in 1898. During this period immigrants, mostly from Asia and the Pacific, came to work on local plantations. Despite this extended agricultural heritage, today the island economy is mainly based on tourism and the US military presence, and is almost entirely dependent on container ships for food and building materials. Yamamoto and Connelly’s artworks serve as optics to view and uncover these histories, even as they concurrently evoke a sense of community by suggesting new and revived modes of belonging to the land.

—Margo Machida and Jaimey Hamilton Faris

Margo Machida: Can you give us a quick overview of the Foster Gardens site and your interest in it for developing your projects?

Lynne Yamamoto: In my piece, Borrowed Time, I took the year that Mary Elizabeth Mikahala Robinson Foster deeded the Garden to the city—1930— as the contextual starting point. I was already interested in that period in terms of architecture in Honolulu as a touchstone for history and memory. Mary Foster (a convert to Theravada Buddhism since about 1893) had been a friend to the Honpa Hongwanji, the Japanese (Jōdo Shinshū) Buddhist temple nearby. In fact, Foster invited Queen Liliʻuokalani to attend the opening of the temple in 1901.

This was significant for me because I grew up attending that temple. I looked at the ways in which many important landmarks for the local Japanese community in the 1920s through 1940s existed in that neighborhood. There was the temple, the Japanese Consulate, a historically Japanese hospital (later Kuakini Medical Center), and a Japanese tea house along Nuʻuanu stream. Bungalow-style homes can still be seen in the neighborhood. This became the architectural basis of my piece.

When I began working on this project I was thinking of a component of David Hammons’s House of the Future (1991) project in South Carolina that also referenced multiple types of architectural features of the homes in the East Side neighborhood of Charleston as a way to remember them, and to create a museum of these types.

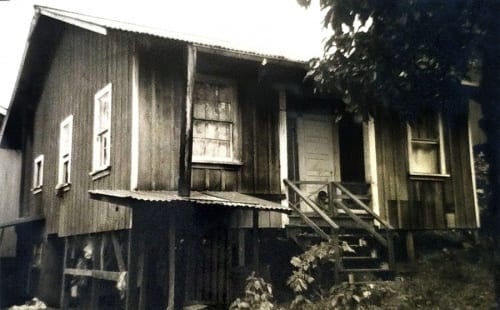

I collected images of the Hakalau Sugar Plantation on the Big Island—the middle managers’ homes were built in the bungalow style with concrete steps, and workers’ houses had board and batten siding with corrugated roofs—both from the 1920s. The houses themselves indicated the hierarchy on the plantation. I was interested in the ways in which the bungalow and plantation styles became somewhat intertwined in a lot of urban architecture in Honolulu, sharing features from both styles. I was also looking at family photographs. In a photo of my aunt, for example, she sits in front of board and batten sided homes.

Sean Connelly: My contribution to the Biennial is Thatch Assembly with Rocks (2060s) (2017). I was thinking about the dominant influence of modern architecture in the islands, in the decades when Hawaiʻi became a state in 1959. I wanted to time travel a bit and offer an alternative moment that didn’t occur in history, in which Indigenous Hawaiian structures were thought of as being modern, versus primitive. Essentially this indexes the history of a group of people becoming disenfranchised and no longer having their land base. The land base is necessary to have the materials to build certain forms of architecture. When the land goes, the materials, forms, and techniques go with it. Ultimately, I wanted to readdress local modernist history by using different building materials and technologies that could declare not the way things have been done, but what could be done differently.

This installation is meant to be a material study that considers the role that certain island-based materials could play in the future recovery of Hawaiian land systems, primarily the ahupuaʻa (a component of the Hawaiian land classification system that provides the basis of a functional material culture and island economy). It speaks to how the history and future of architecture affects the economy of the islands.

In terms of modern architecture, this installation makes reference to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who is credited for creating the first clear span universal space with S. R. Crown Hall, a landmark steel and glass construction built in Chicago, in the decade that also led up to Hawaiʻi becoming a state. The use of steel created a possibility in architecture that hadn’t previously been feasible. But my critique is that the Polynesian canoe house, or hale waʻa, which was invented several thousands years ago if not longer, is the analogue to Mies’s Crown Hall in that it also demands open space without columns. It brings up a blind spot in architectural history.

Jaimey Hamilton Faris: Can each of you talk about how your interest in Foster Garden relates to your artistic practice as a whole?

Yamamoto: In 2007 I had a residency at the Kohler Arts Center in Wisconsin, where I cast a SPAM can. I was interested in the transmutation of material. The can was cast in vitreous china, so rather than being a common foodstuff in tin, it became elevated. As someone who grew up in Hawaiʻi, SPAM is not only important to me personally, but also has an incredible resonance across the Pacific. SPAM was widely distributed throughout the Pacific after the Second World War because it came with US troops and stayed. I was interested in how you could make an object in which the meaning of its circulation and history accrue to it.

Borrowed Time furthers my interest in the architectural history of Hawaiʻi. While living and teaching in New England, I became curious about a familiarity in the landscape. I realized that this was a result of the earliest framed houses in Hawaiʻi coming with the missionaries, having been prefabricated in New England. I began to look anew at the houses in Hawaiʻi on my visits back. Some houses had chimneys even though they were in very hot parts of Honolulu, like Kahala. I began an extended series of photographs of houses in many neighborhoods in Hawaiʻi, which became a book called Chimneys (2008). This led to an interest in the circulation of corrugated iron around the world. It was manufactured first in England and widely used during the Gold Rush in the Western US because it’s a material with which you can very quickly construct shelters. In Hawaiʻi, it was used extensively on the plantations. I have memories of my grandfather’s work shed made with corrugated metal. In response to that, I created a small model, which was digitally scanned and then made into a 3-D print. I also created a work called House for Listening to Rain (2011) for the Spalding House location of the Honolulu Museum of Art. It was a basic shed form referencing the modernist box, with a corrugated roof and seats inside that were sanded tree stumps. It was a way to experience the garden and its view.

Connelly: My installations are forms of research that allow me to apply conceptual and theoretical aspects of my practice as a design theorist and architect. In 2010 I developed an online exhibition called Hawaiʻi Futures, which is mainly a collection of virtual maps and diagrams that illustrates an approach to island-based urbanism for Hawaiʻi. It explores the potential of land use in ways that would bring back an ahupuaʻa-based economy. The project inspired two installation pieces focused on the watershed and environmental cycles from mountain to ocean, and how those cycles impact economic processes. In A Small Area of Land (2013), I worked with 32,000 pounds of rammed earth. In Land Division (2015), I used thousands of branches of strawberry guava, an invasive tree.

For Thatch Assembly with Rocks (2060s), I wanted to work on the kauhale scale, the scale of Indigenous buildings or aggregations of buildings. I began synthesizing different materials, including wood, loulu palm (Pritchardia remota), and rock that would be relatable to viewers in a structure of this scale. This is the largest project I’ve done.

Machida: What kinds of strategic decisions you did make in choosing particular materials and methods of production?

Yamamoto: My structure has two parts. A front part, which is white, and a back part, in which the wood is raw. The white part is more decorative and reflective of the bungalow style. On the plantations, the bungalow style designated the homes of middle management. The back is plainer with lapped railings and board and batten siding that is reflective of workers’ homes. I got all of the wood for my structure from Re-use Hawaiʻi, a nonprofit organization that deconstructs and recycles the wood of many of the types of houses I am referencing.

The piece is structured as a kind of a porch. It was important to provide a place for the visitor in the work to sit and reflect on being there, being present. In terms of orientation, it faces Nuʻuanu Valley. When the trade winds are blowing, they flow beautifully into the structure. I wanted it to be open and face toward Sean’s piece, but to be set back far enough so that off to the left the viewer could see one lamppost, the only thing left of Mary Foster’s home. It marked her driveway.

Connelly: I worked with a Native Hawaiian hale builder named Lopaka Aowohi, who shared a vision to see thatched structures around Hawaiʻi. This installation is currently the only thatched structure in Downtown Honolulu. The main material for the thatching is the loulu palm, which we actually harvested onsite in the gardens. For the structure, I used wood typical of residential construction in Hawaiʻi. The last material components were volcanic rocks, which come from various parts of the island. The wood structure references the influence of modern architecture in Hawaiʻi, while the thatching references the utility of Hawaiian building material and technique. The form of the structure highlights the thermal benefit of the palm. The rocks are placed in the modules in a way that is more aesthetic than functional.

As a final gesture, I wanted to whole structure to be an act of reversal: the thatching, which is typically on the outside of the structure, is pulled inside to highlight the sophistication of thatched construction which can only be admired from inside. Sometimes people refer to the Hawaiian hale in a derogatory manner as being grass shacks. In reversing the structure, I wanted to point out its rigor of construction, which is actually very modern in approach.

Machida: Why architecture? How does it function for you as a connector to your understandings of Hawaiʻi as a locality or as a site?

Yamamoto: Given that I spend most of my time away from Hawaiʻi, I wanted to reflect on how architecture speaks of home for me. At the same time I wanted this work to speak ambivalently. There’s a part of it that is a little run down (front), yet there’s a part that is steadfast (back). I wanted the feeling that this was about memory, about the inability to hold on to something even though you want to. Additionally, as in much of my work, there is a meditation on class.

Although I grew up in Hawaiʻi, I’ve learned more about Hawaiʻi’s complicated history and the relationship between Asian immigrants and the deeper history of the nation and the land since I left. I can’t begin to speak about a Japanese immigrant enclave around Foster Garden without acknowledging what came before. I looked at the Sanborn Maps to think about who lived there in the 1930s. I looked at the census as well, and reflected on what preceded capitalist property ownership—other ways that people belonged to the land. Knowing that Sean and I, and our works, would be in conversation together got me to think broadly and deeply about the history of that place.

Connelly: I was born and raised on Oʻahu between Kalihi and Heʻeia. The first time I went to the mainland was when I was eighteen, and so the basis of my framework is Hawaiʻi. I often find that in order to understand anything, I have to find a way to filter that through the context of Hawaiʻi. This is becoming less and less so now that I’ve been away for years on and off. But it’s something I don’t want to lose, so I strive to continue that relationship to Hawaiʻi as my home and identity. In doing so, I try to strike a chord and to find ways to expand beyond my personal relationship with Hawaiʻi and to think about how the islands can offer important lessons for others.

Machida: One of the interesting implications of your Hawaiʻi Futures project is that you’re drawing on Indigenous models of land use, and what would happen if you took the earlier structures of the ahupuaʻa and juxtaposed them in ways that reconfigure the current-day island environment around sustainable principles. I’m interested in those intersections, the way in which Indigenous knowledge and structures are also taken up by artists to think about how the island environment and local environmentalism can become a kind of global model. I’m curious about some implications of that, and if there are other models coming out of the Pacific that could help us to think about this kind of project.

Connelly: I published Hawaiʻi Futures, which offers the beginning of an idea of the global ahupuaʻa, the year that my nephew was born. I didn’t realize there was a connection, but everything seems to link me back to this place. I think of Hawaiʻi as the biggest place on earth, because its geology is directly linked to the center of our planet. I’m thinking about Hawaiʻi at the planetary scale. I’m also thinking about the lessons that Honolulu as an urban environment can provide. I don’t necessarily see the future continuing to be a separation between what’s considered town and country. If population growth is somewhat inevitable, and we need to house large populations, what are some of our options? How can we reclaim a different type of urbanism? Probably the most inventive way is to think about the structure itself almost becoming an ecology. Choosing loulu palm as a material instead of a concrete masonry unit implies a whole life cycle. Concrete exerts an environmental tax, because of all the water and labor involved in its production. These are the types of things I’m interested in pursuing.

Hamilton Faris: It strikes me, Lynne and Sean, that both of you offer an implicit critique of modernity, modularity, prefabrication, and permanence.

Machida: Each of you devised provisional structures that do not necessarily subscribe to a kind of ideology of permanence, which is important to the critiques that you both are making.

Yamamoto: I find it gratifying to know that there’s a strong movement toward trying to resuscitate older houses despite their age. In a small way, this is an action that works toward sustainability. Communities might feel that they have greater agency in terms of the future of their built environment.

Hamilton Faris: It seems that conceptions of community became a key issue in making the pieces.

Yamamoto: I wanted to be a good neighbor to Sean. It was important that neither of our structures turned its back on the other. Since my structure represents an architectural visitor to the islands, I felt that it needed to be smaller in scale than Sean’s. It was important that there was a sense of the structure embracing you, embracing the seat. Sean’s work has a similar gesture, in which his walls come out to the viewer. Porch forms are important for community. There’s something deeper and richer and really important that happens in the face-to-face contact. We all don’t have enough of that.

Sean Connelly is a Pacific Islander American architect, artist, and urbanist. He holds a doctorate of architecture from the University of Hawaiʻi and a master’s in design in landscape, urbanism, and ecology from Harvard University (with concentrations in real estate development, city making, and urban economics).

Jaimey Hamilton Faris is an associate professor of art history and critical theory at the University of Hawaiʻi, Mānoa, where she is currently working on establishing a digital archive for oral histories of Hawaiʻi’s artists. She also publishes on art’s relation to global trade, markets, economies, and sustainability, including Uncommon Goods: Global Dimensions of the Readymade (Bristol, UK: Intellect, 2013), and her current project, Liquid Archives.

Margo Machida is professor emeritus of art history and Asian American studies at the University of Connecticut. Born and raised in Hawaiʻi, she is a scholar, independent curator, and cultural critic specializing in Asian American art and visual culture. Her publications include Unsettled Visions: Contemporary Asian American Artists and the Social Imaginary (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009). She is an associate editor of the international journal Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas (Brill).

Lynne Yamamoto is a visual artist and educator. Her work engages notions of place and memory, particularly in relation to Hawaiʻi and the Asian Pacific. She is interested in how narratives of seemingly ordinary people open out to have larger implications historically and geographically, and uses materials poetically and tactically. She is Jessie Wells Post Professor of Art at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Further References:

Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa, Native Land and Foreign Desires: Pehea Lā E Pono Ai? How Shall We Live in Harmony? (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1992)

Barnes Riznik, “From Barracks to Family Homes: A Social History of Labor Housing Reform on Hawaiʻi’s Sugar Plantations,” Hawaiian Journal of History 33 (1999): 119–57

Dean Sakamoto, Karla Britton, Marc Treib, and Kenneth Frampton, Hawaiian Modern: The Architecture of Vladimir Ossipoff (New Haven and Honolulu: Yale University Press and Honolulu Museum of Art, 2008)

Mary Jo Valdes and Widya Wijayanti, “The Vernacular Architecture of Palolo Valley,” in A Study of Palolo Valley: Ethnicity, Class, and Spatial Identity, ed. Katherine Tehranian (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi, Mānoa, 1993), 15–26.