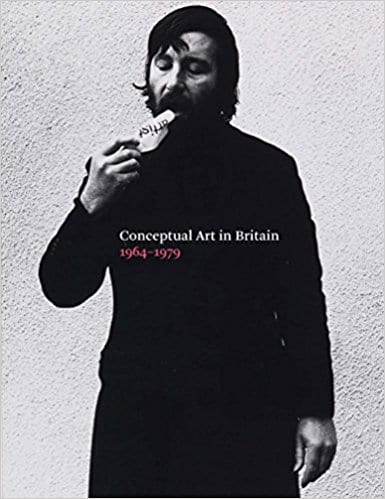

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979

Tate Britain, April 12–August 29, 2016

Andrew Wilson, ed., Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 (London: Tate Britain, 2016)

To say that the strategies of conceptual art are grammatical and the structural norm of all twenty-first-century art is perhaps to paint with a broad brush. It is nonetheless a ubiquity I identified some years ago as the “conceptual turn.”1This is the idea that all contemporary art is based on the omnipresent demeanor, attitude, and set of questions and choices artists make, both consciously and unconsciously, which once seemed only the bailiwick of conceptual artists. To deny the conceptual turn is to ignore the hammer to art immemorial that conceptual art is and was. That conceptual art, from the first Happenings in the mid-1950s onward, recast art as ironic, dematerialized, and more a matter of process than object is perhaps its most powerful quality.

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 at Tate Britain focused on the work of twenty-seven artists, as well as the theory and publishing collective Art & Language, active in the United Kingdom from 1964 to 1979. Its greatest rewards were the selection of artists and its stellar installation. Beyond the usual suspects of conceptual art—the only three were Richard Long, Joseph Kosuth, and Sol LeWitt—it showcased the fantastic but under-exhibited work of many figures, such as Sue Arrowsmith, Keith Arnatt, Braco Dimitrijevic, John Hilliard, Susan Hiller, Victor Burgin, Jan Dibbets, John Latham, Roelof Louw, David Tremlett, and Stephan Willats.

In writing about the exhibition in its catalogue, Alex Farquharson, director of Tate Britain, finds the conflation of conceptual and contemporary art problematic. Yet it is a source of confusion that bears the dividend of persuasion. The melding of conceptual and contemporary, he argues, “reflect[s] the enormous influence the movement has had on subsequent developments” (Foreword, 7). Nonetheless, the Tate Britain’s framing of conceptual art within a fifteen-year time span places limits on the movement’s otherwise limitless Promethean force, even while the intention was to revise and expand the usual story of conceptual art as a mere six-year endeavor2. This is not to say that the limitations were not useful. The show, with its tight focus in time and space, period and geography, brought home a solid sense of conceptual art as born of process, systems, and, above all else, language.

The space of the exhibition was minty cool, brightly lit, and taut like a crisp white bed sheet pulled just so by a punctilious soldier. The word “beautiful” makes sense here but would be inappropriate, as conceptual artists sought to destroy such terms of connoisseurship and delectation in their denial of the conventional art object. The show did have a feel, or dare I say, even a style. One experienced dematerialization writ large, of not only the beautiful masterwork once incarnated in painting and sculpture but also of the very stuff of which matter is made. The galleries were quiet, and the space felt evanescent, even atomic in a granular way. The works collectively read like scientific information—the cerebral data and cognitive records of everyday activities.

To suggest information is also to invoke Information (July 2–September 20, 1970), the conceptual art movement-shaping exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, curated by Kynaston McShine in 1970. McShine brought together an array of conceptual art works in Information by way of the theme of technology. For McShine, the granulation of the art object was not only a matter of philosophy and language, but also, and more precisely, the mediation of text and its perception into information through technological tools, which included everything from the car and typewriter to the computer and satellite. To compare the two exhibitions would be misleading because no such metanarrative existed in Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979, only the useful guiding themes of “new frameworks,” “uses of language,” “the new art,” and “action practice.”

There is no need to fault Tate Britain curator Andrew Wilson for a well-organized and strongly descriptive exhibition. Rather, my intention is to underscore that this theme was markedly absent. It is so even while the ideas and influences of Roy Ascott, the British pioneer of cybernetics in art, are prominent in the exhibition catalogue. References to Ascott’s “Groundcourse” (the foundations class he taught at Ealing College of Art and Design); his theories of cognitive science, behavior, cybernetics, and organismic aesthetics (which appeared in the 1964 essay “The Construction of Change”); and the man himself are frequent, but none of his art was in the exhibition. Curiously, perhaps, his work was not linguistic enough for the show. Perhaps its cybernetic dematerialization felt too material: too much like sculpture sometimes, or too suggestive of technology, too harried, and overall too much for a show with the peculiar but altogether gripping power of aesthetic parsimony.

But work by his student Stephen Willats was present, and happily so. The connection between Ascott and Willats was most obvious in Homeostat Drawing No. 1 (1969), a hand-drawn rendering of a grid of squares connected by arrows. From afar the interconnecting shapes seemed to overlap like the filaments of a woven basket. The drawing points to cybernetic interconnection and flow. A homeostat is a self-adapting, self-regulating device showing lifelike behaviors, such as habituation and learning, through its ability to equilibrate, to strike homeostasis, within a changing environment. The British cybernetician William Ross Ashby built the first homeostat in the years after World War II. For Willats, the drawing does not just represent reality, but forges the possibility of remodeling that reality.

In the following decade, Willats combined anthropology with a cybernetic-systems approach, casting his focus on state-subsidized modern housing towers. His Living with Practical Realities (1978) is a series of three posterlike panels accounting in diagrammatic fashion the everyday life of an elderly woman named Mrs. Moran with whom Willats worked to create the piece. They are bleak and deadpan black-and-white analyses realized in photographs of Skeffington Court, the tower block in Hayes where Mrs. Moran moved in 1975 from central London. The words of Mrs. Moran are present as well, reflecting on aspects of her “code”, “behavior,” “intention,” and “attitude.” Another elemental image, The Twin Towers (1977) is a barebones schema of two tall buildings. The diagram has no photos, just sign-like renderings of the stacked, vertical architectural cages of two skyscrapers, here considered as a “parameter model of social relations.”

Cerebralism was a leitmotif of the show, as the word connects cybernetics, cognitive science, and behavior, while also signaling a general shared quality among the works of quiet, transitory thoughtfulness. The word unfolded in a spectrum of articulation with some artworks bearing a cold, hard, and rational cerebralism, and others a warm, squishy, phenomenal type.

The most aloof, cool, and angry instance of cerebralism was the work by Art & Language, a collaboration of artists that began in 1966 in Coventry with Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin, and would later grow to include Mel Ramsden, Michael Baldwin, Ian Burn, Charles Harrison, Joseph Kosuth, Philip Pilkington, and Michael Corris, among others. Atkinson and Baldwin sought to rethink art as “a collaborative discussion and [matter of] writing rather than object-making,” spearheading the art theory program at the Coventry College of Art 1969–1971 (35). Under their tutelage, art deliquesced into words. Using theory and philosophy as their blade, Atkinson and Baldwin quixotically sought to topple and destroy the medium-specific essentialism of modern painting and sculpture that germinated in the writing of the American art critic Clement Greenberg.

Painting/Sculpture (1966–67) is Art & Language’s wry yet stalwart critique of Greenberg’s ideas about flatness, modernism, and the quiddity—the what-ness or essence—of a given medium. It consists of two small masonite panels covered as though brushless by a machine in gray alkyd paint. They painted the words “PAINTING” and “SCULPTURE” in a similarly mechanical sans-serif script at the bottom of each panel. The work is not foremost about the two objects, but about the discussion about and critique of Greenberg’s ideas to which it points.

Given space in the catalogue but unfortunately not the show, John Latham’s artwork Art and Culture (1966–69) offered a funkier, more Fluxus-oriented cerebralism on the same topic of Greenberg’s writing. It is a leather suitcase containing sundry alchemical items, including a book, labeled bottles filled with liquid and powder, and flasks. Latham checked out Greenberg’s book Art and Culture from the library at St. Martin’s School of Art, where he was a part-time tutor. Following the logic of Greenberg’s thinking, he set out to distill the book to its essence by having friends and students chew individual pages and spit them into a flask, to which he added an acid solution, sodium bicarbonate, and, finally, yeast. While the work further catalyzed the revolutionary deterioration of paternalist modernism within art, Latham’s teaching contract at St. Martin’s was not renewed.

The photography-based conceptual works by John Hilliard and Keith Arnatt struck a midway point in the cerebral spectrum, not so much because of the suggested warmth of celluloid but rather because of the figures and forms that photography, at its core, usually bears. While the intention of the photograph in this context is to be precisely cool and intentionless—authorless, documentarian, and amateur—its effects are warmer simply because physical and bodily forms appear. It is difficult to get away from representation when using such a representational medium. Arnatt’s Self Burial (TV Interference Project) (1969) is a series of photographs showing Arnatt’s body incrementally disappearing into the earth until he is fully gone, underground. It works through the systematic temporality of the art as thought process in this instance, as it is both earthen and technological. The images were randomly screened on German television in October 1969, with one photo each day for two seconds at a time, sometimes interrupting broadcasts at unexpected moments.

Gallery goers were greeted with the warmest cerebralism at the very beginning of the exhibition, in Roelof Louw’s interactive Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges) (1967). With fragrant fruity smells, bright color, and active touch, Soul City was one of the most affecting pieces in the show. It invited viewers to take an orange from the pile, not unlike Félix Gonzalez-Torres’s candy mounds from two decades later, potentially displacing the rest of the fruit while also activating the work as a cybernetic system encompassing viewer, space, and artwork at once.

Ultimately, cerebralism belies the activist holism of conceptual art. While cool, rational, and driven by philosophy, it is an art of hot, materialist politics. This was evidenced in Art & Language’s Dialectical Materialism (1975), a giant text piece that breaks down art into a semiotic matrix of class struggle, paying homage to Leon Trotsky.

There were also feminist materialisms in the exhibition, giving shape to the labor politics of mothering and womanhood, such as Mary Kelly’s Post-Part Document. Analysed Markings and Diary Perspective Scheme (Experimentum Mentis III: Weaning from the Dyad) (1975) and Margaret Harrison’s Homeworkers (1977). Using the Lacanian mirror stage as a theme, Kelly’s Post-Partum Document records her son’s cognitive development and incremental independence, turning everyday maternal labor into art. Harrison’s Homeworkers collages paint, paper, clothing, brooches, buttons, and a household glove onto a wool canvas, creating a palimpsest of her collaborative work with the National Campaign for Homeworkers in London in their bargaining for equal pay. The brown woven canvas documents actions for female laborers after the Equal Pay Act of 1970 failed to concretize higher pay for women doing part-time factory work.

Perhaps the best place to look for this unification of mind and body is in conceptual art’s romanticism. It was everywhere in this exhibition: in its Promethean idealism; in “Romanticism,” Atkinson and Baldwin’s original name for the art theory program at Coventry; and perhaps most vividly in Susan Hiller’s Dedicated to Unknown Artists (1972–6). The piece is made up of over three hundred original postcards depicting waves crashing onto shores of Britain and maps organized in what the artist called a “methodical-methodological approach.” The colorful pictorial nature of the small images strikes a sense of wistfulness, perhaps about the loss of old conventions, or perhaps about the death of art tout court, which is then cut with the cool ratiocination of their careful ordering in grids.

The work in Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 was neither one nor the other, neither cold nor hot, neither logical nor emotional. In keeping with the romanticism at its core, it was everything at once: warm, wet, cold, dry.

Charissa Terranova is associate professor of aesthetic studies at the University of Texas at Dallas, author of Art as Organism: Biology and the Evolution of the Digital Image (2016) and Automotive Prosthetic: Technological Mediation and the Car in Conceptual Art (2014), and coeditor (with Meredith Tromble) of The Routledge Companion to Biology in Art and Architecture (2016). She is the inaugural director and curator of Centraltrak: The UT Dallas Artists Residency, and regularly curates and writes art criticism. With Davidson College Professor of Biology Dave Wessner, in February 2016 she cocurated Gut Instinct: Art, Design, and the Microbiome, an online exhibition about art, the gut-brain axis, and gastrointestinal microbiome. In the fall of 2015 at Gray Matters Gallery in Dallas, Texas Terranova curated Chirality: Defiant Mirror Images, an exhibition about art and the scientific concept of “chirality,” or non-superimposable mirror images.