Focusing on Risham Majeed’s exhibition Made to Move: African Nomadic Design (March 22–April 21, 2017, Handwerker Gallery, Ithaca College, Ithaca, New York), this conversation explores how installations of art can resist traditional narratives and point toward new ways of framing and interpreting the history of art—in short, toward the possibility of a decolonized museum space. The exhibition material, coming from nomadic Tuareg and Rendille cultures, resists typical museological categories, posing challenges to the conventions of curatorial practice and necessitating new design solutions.

In April 2017, Elizabeth Rodini visited Ithaca and met with Majeed and some of the students who helped curate the exhibition. What follows is an edited transcript of conversations between Majeed and Rodini that took place in April 2017 at two venues: the Handwerker Gallery at Ithaca College, and the Rockefeller Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

This conversation explores Made to Move as a response to mainstream art museum approaches to exhibiting African art, architecture, domestic objects, and impermanent, transient materials.

Elizabeth Rodini: Tell us about the origins of this exhibition and how you used it at Ithaca College.

Risham Majeed: From 2011 to 14, I worked with the Qatar Museums Authority on a large exhibition as the assistant curator to Susan Vogel, one of my PhD advisors. It was an ambitious project that revolved around actually exhibiting architecture, including three different types of tents, and showing them in a way that accentuated their aesthetics and made their structures visible. The exhibition was designed by Zaha Hadid, who died last year, and was part of a partnership with the Brooklyn Museum, but it was put on hold indefinitely. I then finished my PhD and came to work at Ithaca College.

I had done a lot of research on nomadic architecture in European and American archives during that time, and by chance, when I was visiting the storage facilities of the Johnson Museum at Cornell University—and this immediately goes to questions of reception history—I found a trove of nomadic material. Through no fault of the museum, which doesn’t have specialists working in this area, some of it was mislabeled. I think it’s fair to say that the materials presented a bit of a conundrum. I was searching for an exhibition project using local collections for some courses at Ithaca College, and this was a perfect opportunity to reevaluate the ideas of the previous exhibition while also implementing concepts that had been shelved, essentially.

Rodini: And you did that through a series of courses?

Majeed: In fall 2016 I taught an exhibition seminar, an upper-level course oriented toward the place of tent architecture in architectural history, with a focus on African art history and a consideration of display and design. The museums, education, and outreach class that I taught in spring 2017 reexamined the curatorial designs devised in the fall and executed a revised version based on the constraints and parameters of the objects and the gallery space.

Rodini: This was a chance to explore conceptual questions about the field of African art in the space of a gallery. What were some of the exhibitionary modes you considered, and where did you land?

Majeed: The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the well-known efforts to “modernize” African art in terms of its relationship to Cubism, abstraction, and Modernist Primitivism left a stigma on the presentation of African art in a white cube setting.1 I thought that approach came with too much baggage, and was ultimately too boutiquey. I wanted to give a sense of life and use to these museum objects without replicating a false context in the space of the museum.

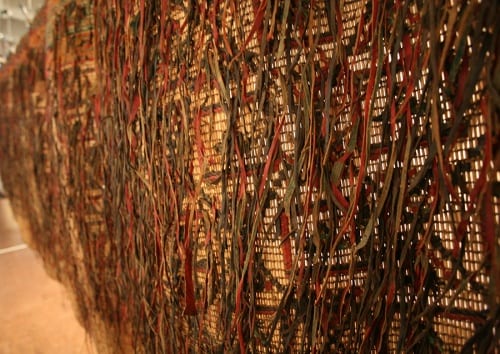

Rodini: This wall is a great example of a moderated approach. Can you describe your curatorial thought process here?

Majeed: These rather rough Rendille objects are already resistant to museum looking. I wanted to enliven them by giving a hint of original context through texture, but always in fragmentation. Such vessels would have been tied to the sidewall of the tent armature, which is suggested here through mismatched photographs that give you a sense of the pattern and texture of its aesthetic components without trying to replicate it literally.

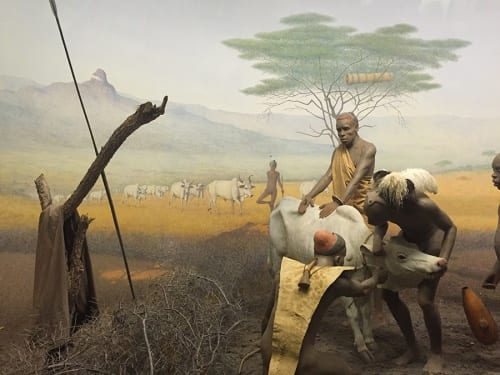

Rodini: So this is an alternative to the easy language of the diorama?

Majeed: I was not interested in fooling the viewer through simulation, and I did not want to advocate the false transparency that a diorama vignette claims for itself. As a curatorial and pedagogical solution, I decided to consistently maintain that any sense of consensual authenticity or definitive origin is no longer available to us in a gallery setting. In terms of exhibition design, we also faced the challenge of balancing the two cultures, Rendille and Tuareg, while highlighting their most distinctive visual elements. Rendille objects have a very elegant but stark insistence on materiality.

Rodini: As opposed to the familiarity of some of the Tuareg material where the beauty is evident: this is an art museum object, while the Rendille objects might spark questions like, why is this an art museum object? They’re not conventionally beautiful; they’re rough, thick, and clearly utilitarian. Your layout eases people in, with Tuareg first and Rendille second.

Majeed: Tuareg posts are delicate, refined, and produce graphic shadows. In our exhibition they also draw you into an environment of posts and tent wall in which you are enclosed, and it’s comforting because it’s an aesthetically understandable and consequently pleasing environment.2

Rodini: Gender is one of the important themes here. Is it a coincidence that the objects that are produced by men—the Tuareg posts—are the most familiar?

Majeed: No. If there is anything that is going to make it to the art museum it is the Tuareg posts. And I very much wanted to present nomadic material first in terms of its aesthetics. The way nomadic cultures have been experienced has been through a male ethnographic lens. These early travelers engaged primarily with the men, who exaggerate their role in the gendered division of labor. For example, Alois Musil, an ethnographer working in Saudi Arabia with the Bedouin (another nomadic culture), reported that men directed the women in their handling of the tents—which is absolutely not the case.3

Similarly, in Rendille culture, before men are married there is a ritual act of removing themselves from women and going to the desert, which includes the symbolic construction of a miniature tent. Ethnographic filmmakers have recorded the Rendille men laughing because the men had no idea what they were doing—the laughter was coming from embarrassment over not knowing the process, but also because they were doing women’s work. For this reason, we included a clip of this film in our exhibition, showing women building.

Rodini: You mentioned earlier that each adult woman owns her tent. She owns the knowledge of the making of the tent, she controls where it goes, and she knows how to put it together—without the woman’s tent there is no communal site.

Majeed: There is no civilization of space without the tent. The civilizing gesture is creating the tent, marking yourself off from your environment.

Rodini: Here’s another provocative dialogue with the museum, because this is also the sort of material that’s fragile and not collected: it’s a textile, or it’s matting that doesn’t survive, or it’s disassembled because it’s large. These things don’t convert easily into museum objects. Again, you have objects produced by women that are not included in the emerging canon of African art.

Majeed: The resistance of these objects to the museum space is interesting: the idea of permanence and arresting an object before its life is finished is not universal. A tent is created on the occasion of a woman’s marriage, and she has it for the rest of her life. A piece of it will be used to make her daughter’s tent, and that’s how it goes. The tent is not meant to have a lifespan beyond the family that lives in it. The idea of memorializing these objects that were never meant to last beyond their usefulness is somewhat antithetical to their personalities.

Rodini: That also rubs up again against the diorama, which embodies permanence by fixing place. You mentioned earlier that the wall of the exhibition dedicated to repaired objects is the one place in the show where you mixed Tuareg and Rendille cultures. Was one of your motives in emphasizing repair and reuse to dislodge that trope of permanence that’s so critical to the museum?

Majeed: It’s not that they are fragile, but that they have been used and that use can be communicated through the ways they have been diligently repaired many times, which also indicates how valuable they were to their owners. There is an element of the sense of longing that we associate with repairing, in keeping something in the family—but I think as soon as a newer object was affordable that was more useful, the broken one would likely be discarded.

Rodini: One of the things we talked about earlier with your student Lisa Peck was the question of how you activate objects in a gallery that are mobile, functional, and domestic in the sense of being lived with.4 How do you work between conventional museum strategies and more animated modes of presentation? Did you discuss these challenges as a class? What were some ideas you discarded versus what you settled on?

Majeed: By the end of the seminar, we knew what we didn’t want, but actually coming up with what we did want was more challenging, in part because of conservation issues and the objects themselves. We all wanted to run the woven perimeter tent wall down the center of the room but we had concerns about the practicality of this, because Tuareg tent mats have never, to my knowledge, been shown as walls. They’re always displayed rolled—Lisa described this as an “archival” presentation. They’re treated as textiles in a vault rather than as three–dimensional space dividers, rolled to show partial elements of the design but without communicating a sense of scale, the enclosure that it produces, or its porosity, which can only be seen by the quality of light that goes through it.5

Rodini: Let’s bring that point back to the strategies for showing the life of the object—what was your approach to installing the Tuareg goatskin bags?

Majeed: We wanted to show them as if in use without replicating the entire contextual environment of that use, because we were not trying to give a comprehensive presentation of Tuareg culture. Rather, we chose to highlight certain material properties or aesthetic coherence over a synoptic, ethnographic approach. The bags are stuffed with archival paper and they are three-dimensional, as they would have been when on the move. You get a sense of that overlapping texture of fringe, leather, and color because they would have been tied in a row according to even weight distribution on a pack animal. You would never experience them as isolated things on their own.

Rodini: They’re piled up like a bunch of cushions would be thrown on a couch—there’s a sense of interactivity.

Majeed: We installed them as if they were being used or moved, but also made sure to not obscure them to the point where they’re not recognizable as aesthetic objects. They’re installed slightly above eye level, and one is hung as it would have been on a camel. Camel height, if you will.

Rodini: But you chose to put the smaller Tuareg prayer mats up on shelves, not down near floor level. I suppose that’s partly a practical issue—someone might kick them.

Majeed: Part of alerting you to other uses or meanings of utilitarian objects is to make them useless, right? That’s what museums do. You turn a bowl upside down where it has no possibility of use, the way that the Tuareg bowls are hanging on the wall in the exhibition. Other vessels are nonsensically installed on their sides—of course the milk would have spilled out! But interrupting or suspending use helps when you’re trying to reposition the viewer to consider something aesthetically, as Svetlana Alpers, Susan Vogel, and others have pointed out for other kinds of museum objects.6

Rodini: We’re really talking about a rhetoric of installation.

Majeed: In other cases, generating the atmosphere of the object is more useful. For the perimeter mat that runs down the middle of the gallery, it’s more effective to see how it behaves as architecture and shapes space, rather than to see it flat as a textile or pattern. In this installation the viewer can appreciate both aspects.

Rodini: Let’s turn to architecture, because this is another place where these nomadic materials run up against traditional museum contents and approaches.

Majeed: Exhibiting architecture is an impossible thing. On the one hand, architecture is always on display: it’s not moving, it’s firmly situated, and it’s site-specific. That permanence also means that it can only ever be represented in galleries through simulation: models or drawings, plans, photographs—essentially the object either as miniature, reductive diagram, or fragment. Exhibitions of architecture are not object-based installations, but more like an archive of a building.7 Nomadic objects, on the other hand, are already on a human and accessible scale, so the structural aspects of the tent are not simulated here: they are here.

Tents invert so many ideas about architecture and beg the question, what is architecture? This is one of the other big issues in the show, to address how much our concepts of architecture have prevented us from understanding structures that are “transient but not temporary,” to borrow Labelle Prussin’s elegant characterization.8 The way nomadic women reproduce something is a way of affirming a good solution; innovation becomes unnecessary if something is continuing to do the work that it is supposed to do.

Rodini: This is more material that works against the grain of the museum. In this case, it contradicts notions of linear development and the novel or exemplary object.

Majeed: Most of the time we are looking at the singularity of an object, especially in an art museum collection. Seriality is not exactly the business of art, so I wanted to show a range of different types of posts to evince that there is a great deal of variety within the accepted parameters of form, structure, and efficacy.

Rodini: Your ordering of the Tuareg posts creates a hierarchy of quality while also showing the continuity and a widespread availability of these forms and materials.

Majeed: Yes, connoisseurship! That dirty word. But that’s exactly the skill that sameness hones, in the Morellian sense. This installation challenge was quite successful in getting students to understand how to distinguish and evaluate design.

Rodini: On a related topic, your student Karen Macke used language in her exhibition tour that highlighted sustainability and reuse.9 This terminology can be a way of making connections, but it also romanticizes cultures that “lived simply” and quite literally “used every part of the goat.”

Majeed: But we are not talking about subsistence living. Within the bounds of living wisely you also have space for luxury. The Tuareg leather boxes are jewel-like and beautiful. Their form and function are perfectly aligned. They’re called “trifle boxes”—probably named by a man—makeup and perfume are hardly trifles. They’re expensive and acquired through trade in urban markets. The delicacy of the boxes expresses personal refinement.

Rodini: I’d like to broaden our conversation to consider the historiographical and museological frames of your exhibition. Can you talk about the categorizations of Islamic art vis-à-vis African art?

Majeed: These are contested categories. The Tuareg are practicing Muslims now, but Islam arrived in North Africa in the seventh and eighth centuries, and the Tuareg have lived in this region for far longer and are descendants of the indigenous Berber people. However the idea of North Africa as part of Africa is also contested—because as part of La Grande France it was then l’Afrique blanche (now Afrique du Nord), which is how it’s predominantly still treated in museums: North Africa is Islamic. If you go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they have Morocco in the Islamic galleries and Tuareg in storage (under the purview of the Department of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas), even after the 2011 reinstallation of the Islamic galleries. A fascinating intervention would be to consider North African art in association with sub-Saharan Africa. Much of the turn toward the global in scholarship today is invested in exploring such networks of continuous and fluid exchange in these regions.

Rodini: Rather than always facing North Africa toward the Mediterranean and Europe.

Majeed: The Tuareg traverse the Sahara, which includes parts of Mali, Niger, Mauretania, Morocco, and southern Algeria. They have as much in common with North African Islam as they do with sub-Saharan ethnic groups, much more than most museum presentations would have you believe. That’s the beauty of nomads: in defying boundaries, they reveal how arbitrary boundaries really are.

Rodini: This material challenges the entrenched geography of the museum. Maybe that’s another way of realizing a decolonized museum, by breaking through the structure of the museum and disrupting the things it wants to tell us.

Majeed: The intellectual moats that we have constructed around certain types of objects inhibit access to new ideas. With African art the concern is always that nobody knows anything about it, so you constantly have to make the same claims over and over. Those claims are so tied to notions about Africa generated during the colonial period, yet we are latently reifying them again, and again, and again. Why don’t we discard them?

Rodini: That concern motivated some of my earlier questions to you about the overlap or not of Rendille and Tuareg in your exhibition. Do you want to teach people that these groups are very different, or are you comfortable with some level of fluidity?

Majeed: Across the continent and across the world, nomads share many of the same values and approaches to design that often relate them more to one another than to their geographically proximate ethnic groups. Rendille nomads have more in common with the Tuareg than they do with indigenous sedentary groups. There is a certain idea of a nomadic aesthetic, a nomadic lifestyle that permeates vastly different, territorially separated cultures. Thematic approaches to installations and exhibitions can help make connections across cultures, rather than containing them according to national boundaries that may or may not be meaningful.

Rodini: There is a different map of the world being imagined in your exhibition. It’s unfixed.

Majeed: Nomads have historically been reviled. When Fernand Braudel wrote his history of the Mediterranean, he characterized nomads as parasites on sedentary communities, because he associated civilization with fixed cities—and thus with our idea of architecture as something permanent.10

Rodini: Which returns us to gender, because “civilizing” is a very masculine endeavor in that framework but in your exhibition the makers of place, in terms of architecture, are the women.

Majeed: Nearly every notion of architecture that we have is inverted in nomadic societies. That’s why I wanted to include the film showing women physically building the tents. The film also brought living, breathing people into the exhibition, so that the object doesn’t always come anonymously from Africa. This was a major issue for the class. We had to acknowledge that somebody made this. You can’t treat the entire ethnic group as author anymore. We used the term “unidentified”11 on our labels, meaning that when these works were collected in the field, nobody bothered to identify who made them. It’s a kind of provenance, too.

Rodini: That takes us back to your “discovery” in the Johnson storage vaults. It reminds me of reading Oleg Grabar on Islamic art at the Met in 1976.12 I’m struck by his reliance on negative language to describe the curatorial approach: it’s not linear, not about the masterpiece, not about the narrative subject.

Majeed: Isn’t that also about dealing with museum visitors’ expectations? It’s managing expectations for Islamic art or, in our case, African art.

Rodini: That’s exactly where I was going. You’re right—these are parts of the same conversation. Your notion that a modular, repetitive mode of building be thought of as an effective solution, disrupting expectations of development and linearity—

Majeed: And progress.

Rodini: And progress—this is a positive framework and an alternative to the “it’s not this” kind of approach. This seems like a good way of thinking about curating today.

Majeed: Even in teaching and looking and dealing with African art at large, I find myself asking, are we there yet? It’s always a recalibration in the beginning: “it’s not this.” It’s not primitive, it’s not modern. We don’t need to do that with Chinese art, for example. With African art I think its reception is still somehow tied to race, and that’s something that the field of African art has sublimated but not dealt with adequately, because we’ve been thinking that we’ve transcended race in some way, which is just a ridiculous notion.

Rodini: In what ways do museums continue to make the field of African art?

Majeed: When Grabar wrote that article in the 1970s, it was the Met’s first permanent installation of Islamic art. So the Met “created” Islamic art in a way that was formative for that field. The Met did the same thing for African art in 1982, with the Rockefeller Wing, but it was still called the Department of Primitive Art when it first opened. Go down to the Rockefeller Wing now and it really is like 1982 in there, because the museum still has to disrupt persistent ideas of atemporality, geography, ethnic groups vs. “tribes,” and the lack of cross-cultural interaction—all those “myths” that Suzanne Blier and Anthony Appiah enumerated.13 But the Met is in the middle of a reinstallation project of the permanent galleries of African art.

Rodini: Is this a place where more dialogue between art museums and other sorts of museums might be productive?

Majeed: The ethnographic galleries in the American Museum of Natural History are essentially period rooms now, even though they are aware that they have “art” in their midst. Yet, what would a reinstallation of the natural history museum look like? I mean, isn’t it always going to be a period room?

Rodini: The collection is coming to represent itself.

Majeed: In the same way, I think the Rockefeller Wing at the Met is a period room.14 Its installation basically has not changed in nearly forty years. The Oceanic wing has been reinstalled and it’s spectacular, because that gallery’s architecture is sensitive to the needs of the objects, and that synergy results in a resonant experience. Many of those objects are architectural, too, and they are treated as such. I’m looking forward to the reinstallation of the African galleries in the Rockefeller Wing; that has the potential to give us a sense of how far we have come and still have to go.

Select Bibliography

Note: For materials related specifically to African nomadic cultures see the bibliography in the Made to Move: African Nomadic Design catalogue.

Albers, Anni. “The Pliable Plane: Textiles in Architecture.” Perspecta 4 (1957): 36–41.

Alpers, Svetlana. “The Museum as a Way of Seeing.” In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, eds., Ivan Karp and Steven Levine, 25–32. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991.

Appiah, Kwame Anthony. “Why Africa? Why Art?” In Africa: The Art of a Continent: 100 Works of Power and Beauty, edited by Tom Phillips, 21–26. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1996.

Blier, Suzanne. “Enduring Myths of African Art.” In Africa: The Art of a Continent: 100 Works of Power and Beauty, edited by Tom Phillips, 26–32. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1996.

Braudel, Fernand. Memory and the Mediterranean. Edited by Roselyne de Ayala and Paule Braudel, translated by Sîan Reynolds. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001.

Cole, Doris. From Tipi to Skyscraper: A History of Women in Architecture. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1973.

Le Corbusier. Towards a New Architecture. Translated with an introduction by Frederick

Etchells. New York: Dover Books, 1986.

Drew, Philip. New Tent Architecture. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2008.

__________. Tensile Architecture. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1980.

Ezra, Kate. “Collecting African Art at New York’s Museum of Primitive Art.” In Representing Africa in American Art Museums: A Century of Collecting and Display, edited by Kathleen Bickford Berzock and Christa Clarke, 122–49. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011.

Faegre, Torvald. Tents: Architecture of the Nomads. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1979.

Grabar, Oleg. “An Art of the Object.” Artforum 14 (1976): 36–43.

Hitchcock, Henry-Russell and Philip Johnson, The International Style: Architecture since 1922. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1932.

Johnson, Douglas L. “Nomadism and Desertification in Africa and the Middle East.” GeoJournal 31 (September 1993): 51–66.

Kasfir, Sidney Littlefield. “One Tribe, One Style? Paradigms in the Historiography of African Art.” History in Africa 11 (January 1984): 163–93.

Kuhlmann, Dörte. Gender Studies in Architecture: Space, Power and Difference. London and New York: Routledge, 2013.

MacDonald, Angus J. Structure and Architecture. London and New York: Taylor & Francis, 2001.

Massey, Doreen. Space, Place and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994.

Nelson, Steven. “Notes from the Field: Time.” Art Bulletin 95 (2013): 370–71.

Pelkonen, Eeva-Liisa, Carson Chan, and David Andrew Tasman, eds. Exhibiting Architecture: A Paradox? New Haven: Yale School of Architecture, 2015.

Prussin, Labelle. African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place, and Gender. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995.

Rudofsky, Bernard. Architecture without Architects: An Introduction to Nonpedigreed Architecture. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1964.

Semper, Gottfried. The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings. Translated by Harry Francis Mallgrave and Wolfgang Herrman. Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Urbach, Henry. “Exhibition as Atmosphere.” Log, no. 20: Curating Architecture (Fall 2010): 11–17.

Viollet-le-Duc, Eugène-Emmanuel. Histoire de l’habitation humaine depuis les temps pré-historiques jusqua’à nos jours. Paris: Bibliothèque d’éducation et de récréation, 1875.

Vogel, Susan. “Introduction.” In ART/Artifact: African Art in Anthropology Collections, edited by Arthur C. Danto, 11–17. New York: Center for African Art, 1988.

__________. “Bringing African Art to the Metropolitan Museum.” African Arts 15 (February 1982): 38–45.

Weresch, Katharina. Architecture, Civilization, Gender: Residential Building, the Civilizing Process of Dwelling Practices and Changes in the Family. Zürich: Verlag, 2015.

Risham Majeed joined the department of art history at Ithaca College in 2015 after completing her Ph.D. at Columbia University. Her dissertation, Primitive before Primitivism: Medieval and African Art in the 19th century, examined how Romanesque and African sculpture were together treated as “primitive” through various new reproductive media, culminating in the foundation of two seminal museums at the Trocadéro palace: the Museum of Ethnography and the Museum of Comparative Sculpture. She has recently presented her work on Meyer Schapiro at the Columbia University Seminar; it is forthcoming in RES: anthropology and aesthetics, as an article entitled, “Against Primitivism: Meyer Schapiro’s Early Writings on African and Medieval Art.” Her current projects include defining the notion of “primitive” at the Barnes Foundation, based on archival work conducted at that museum, and editing her doctoral research into a book length study of the Trocadéro museums.

At Ithaca College, Majeed teaches courses on the history of museums, African art, and medieval art. This Spring she will organize an inter-disciplinary symposium “Primitivism before Modernism” hosted by the college. In Fall 2018, Majeed will teach a second Exhibition Seminar that will mount an exhibition on the theme of “African Art and Authenticity” in Spring 2019 at the college’s Handwerker Gallery. This will be another collaboration with Cornell University’s Johnson Museum, and will feature additional loan objects from NYC collections. Majeed is a member of the College Art Association’s Museum Committee and has been a lecturer at the Met Cloisters since 2006.

Elizabeth Rodini works at the intersection of museums and academia, and has lectured and published widely on museum and collection history, museum scholarship, and cultural landscapes. As founding director of the Program in Museums and Society at Johns Hopkins University, she oversaw over 50 museum-university collaborations, resulting in exhibitions, educational initiatives, web projects, and programming. She has curated exhibitions at the Smart Museum of Art, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and the Walters Art Museum. She received her PhD from the University of Chicago.

Rodini’s historical research centers on cross-cultural encounters in early modern Venice, particularly matters of object mobility, recontextualization, and reuse. Recent publications include “Imitation as a Mercantile Strategy: The Case of Damascene Ware,” in Typical Venice? Venetian Commodities, 13th-16th Centuries (Brepols, at press), and “Mobile Things: On the Origins and Meanings of Levantine Objects in Early Modern Venice,” Art History (2018). She is a member of the working team for Mobility of Objects across Boundaries, a British Arts and Humanities Research Council project, and will pursue related work in the spring of 2018 as a Visiting Fellow at the Bard Graduate Center in New York City. She is currently completing a book-length study of Gentile Bellini’s portrait of Mehmet II, constructed as an object biography and methodological reader, and launching a new project on the politics of heritage preservation.

- The starkly decontextualized presentation of African art, without any of its ritual attachments, begins with Alfred Stieglitz’s exhibition at 291 held in 1914, Statuary in Wood by African Savages: The Root of Modern Art. Here, African art appeared against a background of brightly colored construction paper assembled in abstract designs on the walls; in subsequent exhibitions it was installed alongside works by Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and others. The crystalline transparency of the white cube was applied to African art in the seminal exhibition African Negro Art, curated by James Johnson Sweeney and held at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1935. This mode of presentation was maintained at the Museum of Primitive Art, which was founded across the street from MoMA in 1954 with Robert Goldwater as its director. This style of installation perpetuated associations of abstraction and other formal issues that preoccupied Modernists, but had little to do with African art. ↩

- Neither of us had yet seen Ernesto Neto’s controversial tent, titled Un Sagrado Lugar (A Sacred Place) at the 2017 Venice Biennale, where both Neto’s project and the excess ‘comfort’ of visitors (drumming, snoozing, stretching inside it) have come under criticism as a form of colonial appropriation. Neto’s tent was part of the “Pavilion of Shamanism,” which harkens to conventions of neo-primitivism. Neo-primitivism was widely critiqued in the 1980s and 1990s, especially in the wake of William Rubin’s exhibition “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art held at MoMA in 1984 and Jean Hubert-Martin’s equally controversial response, Magiciens de la Terre, at the Centres Georges Pompidou in 1989. With regard to Neto, see Holland Cotter, “Venice Biennale: Whose Reflection Do You See?” The New York Times, May 22, 2017. ↩

- See Alois Musil, The Manners and Customs of the Rwala Bedouin (New York: American Geographical Society, 1928). ↩

- Lisa Peck, Ithaca College Class of 2017. Peck majored in art history and was a student in Majeed’s exhibition seminar taught in the fall of 2016. ↩

- There was no precedent in showing the mat completely rolled out, so Majeed had to innovate the display mechanism. Matthew Glaysher, a lecturer in the department of art history at Ithaca College, effectively implemented this idea with students in his own class, museum practices. ↩

- Svetlana Alpers, “The Museum as a Way of Seeing,” in Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, eds. Ivan Karp and Steven Levine (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), p. 25-32. Susan Vogel, “Introduction,” in Arthur C. Danto, ed., Art/Artifact: African Art in Anthropology Collections (New York: The Center for African Art, 1988), p. 11-17. ↩

- This conundrum has been a part of the conversation of exhibiting architecture from the very first exhibitions of architecture, for example, at MoMA. Philip Johnson’s 1932 exhibition, Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, included models, drawings, and photographs commissioned especially for the exhibition. The only instance in which tents have been considered in terms of architecture was in Bernard Rudofsky’s 1964 exhibition, Architecture without Architects, also at MoMA. It featured monumental enlargements of photographs of vernacular architecture from all around the world. See also Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen, Carson Chan, and David Andrew Tasman, ed. Exhibiting Architecture: A Paradox? (New Haven: Yale School of Architecture, 2015). ↩

- Labelle Prussin, a key scholar of African architectural history, posited many of the arguments that Made to Move takes up and expands on in her important book African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place, and Gender (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995). ↩

- Karen Macke, Ithaca College class of 2017. Macke majored in history and did a minor in museum studies, while also working at the Seward House Museum in Auburn, New York. She was a student in Majeed’s museums, education, and outreach class taught in the spring of 2017. ↩

- Braudel writes, “The desert has had a powerful impact on the physical and human life of the sea. In human terms, every summer saw the desert nomads, a devastating multitude of men, women, children and animals, descend on the coast, pitching camp with their black tents woven from goat or camel hair. As neighbours, they could be troublesome, at times marauding. Like the mountain people, high above the fragile steps of civilization, the nomads were another perpetual menace. Every successful civilization on the Mediterranean coast was obliged to define its stance towards the mountain dweller and nomad, whether exploiting them, fighting them off, reaching some compromise with one another, sometimes even keeping both of them at bay.” Fernand Braudel, Memory and the Mediterranean, ed. Roselyne de Ayala and Paule Braudel, trans. Sîan Reynolds (New York: Knopf, 2001), 7. ↩

- Increasingly, collections of African art have moved toward acknowledging that the authors of the works in question were of course known to their own local communities by adding “unidentified” or “unrecorded” artist to their labels. The point is to recognize that the synapses in information arise from our own, albeit earlier, lack of interest in recording the names of African artists when they were initially collected. ↩

- Oleg Grabar reviewed the first permanent installation of Islamic art at the Met in “An Art of the Object,” Artforum 14 (1976): 36–43. ↩

- See Kwame Anthony Appiah, “Why Africa? Why Art?” and Suzanne Blier, “Enduring Myths of African Art,” in Africa: The Art of a Continent: 100 Works of Power and Beauty, exh. cat. (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1996), 21–32. ↩

- This is an argument made by Majeed in her article, “Excuse Me, Is This a Church? Display as Content at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Journal of Museum Education, September 2017. ↩