This is the last in a series of conversations led by Caitlin Masley-Charlet, focused on the utility and scope of artists residencies: how they serve artists, what artists do for them, and how they function as sites for production, experimentation, access to equipment and making friends in new places.

When I first started at Guttenberg Arts, a residency program in New Jersey, as Deputy Director, the leadership wanted to explore various projects through which the artists-in-residence could connect in meaningful ways to the local community. Our main focus was how Guttenberg Arts could be in direct service to the community of Guttenberg and create lasting relationships through the visual arts. After seeing many applications for the already established studio-based artist residency program, we noticed how many of those artists already focused on community involvement as part of their practice. Thus, the Community Artist-in-Residence position was created, and Elisabeth Smolarz was chosen to be the first. For her project The Encyclopedia of Things (September 2017–August 2019), funded in part by the National Endowment for the Arts, Smolarz is visiting the homes of two hundred Guttenberg residents to create a collection of distinct portraits which, together, will build a composite sketch of Guttenberg. This project will bring Smolarz back to Guttenberg long after her official residency ends, and has initiated many lifelong friendships.

I recently met Smolarz at Parsons, where she teaches photography, to catch up on how the project is going. I got a surprise sneak peek of Smolarz’s new work for an upcoming show in Czech Republic and a past show in China. Smolarz begins by explaining her process on how the pieces came about.

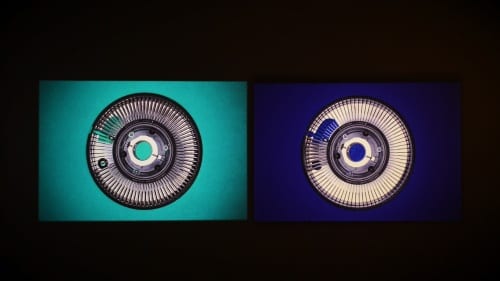

Elisabeth Smolarz: I began to think about nostalgia and obsolete futures in this new work. I got the carousels from Materials from the Arts. The Met had just donated all their slide projector equipment to them, and I was just there one day and took two of them. When one of my younger studio mates looked at the carousels and asked what it was, it led me to make an ode to the slide projector. It’s all nostalgia and memory. We all remember the crappy presentations we used to give with them, and the drawers full of old slides before the digital “revolution”. And let’s not forget the traditional family holiday shows we were forced to sit through, and the constant loading and unloading of the carousels.

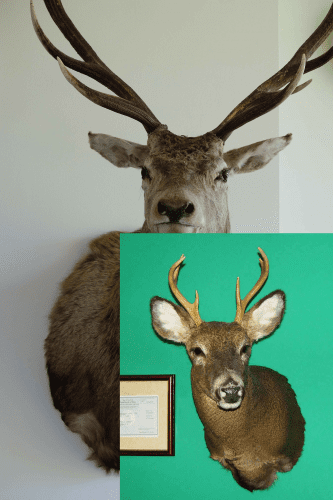

Thinking about nostalgia and the ritual of image production, my current project Jelen is the result of a collaboration with Markéta Othová, and is currently on view at the Foundation and Center for Contemporary Arts in Prague as part of Apparatus 2.0: The Unreliable Library. Pulling from our personal archives of images made over the past three decades taken through the lenses of different apparatuses, our collaboration echoes the synchronicities, losses of control, and errors in image and language. Jelen is the exchange of high and low resolution images—of pixels making their way into reality and coming together as a semi-archaic object, a postcard-size fanfold book. Predominantly found in souvenir shops in the twentieth century, the fanfold book becomes a trophy glorifying the hunt for images. Slides and fanfold books—do you remember?

Caitlin Masley-Charlet: Yeah, I remember the tiny white labels for grant applications and the perfect tiny nabbed shares to write on the labels (laughing). Along these lines, when did you first start applying to artist residencies? What motivated you to apply? And what was your first reaction to a rejection; what kept you applying?

Smolarz: Within the first year after graduating from the State Academy for Fine Arts in Stuttgart, Germany, I moved to New York and was quite overwhelmed. The realities of starting a new life as an artist in a new country were so enormous and surreal that I decided to go to the place where “elves” exist, so I looked for a way to get to Iceland and learned through a fellow artist about an artist residency there. In retrospect I really needed a break from New York. The Samband íslenskra myndlistarmanna (SIM) residency in Reykjavik was very peaceful—there was only one other artist there who became a dear friend.

I’ve had my share of rejection letters. Getting rejected is always disappointing, but I was told early on by a mentor that the application formula goes as follows: apply for twenty in order to get one. Don’t get discouraged, and keep applying. To give you an example, it took a decade of applying for me to get the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (LMCC) WorkSpace program residency. To me, this was the holy grail of residencies in New York. It is the most prestigious residency that I have done so far. In addition to providing free studio spaces for thirty artists and writers in Lower Manhattan, the residency is run like a well-oiled machine. The team is extremely supportive and accommodating, and on top of the frequent studio visits with curators and critics, we have access to facilities like NYU’s LaGuardia Studios and Materials for the Arts. It’s a truly wonderful group of writers and artists, and I feel very lucky to be part of the community. Plus there is a stipend!

Masley-Charlet: What do you look for when applying to residencies?

Smolarz: Residencies are all about experimentation and community for me. Working with new equipment and materials as well as meeting new artists is crucial, as the cross-pollination is oftentimes what leads me to a new direction in my work.

There is always a lot of excitement every time I start a new residency. Being taken out of my everyday structure feels liberating, and it’s inspiring to be in a new setting. It’s almost like starting over, mixed with contemplation and self-examination.

Nowadays I look for residencies that are run professionally, since I’ve had a few challenging experiences in the past. Currently I am applying for studio residencies in New York because of the two projects—a film and a book—that I am working on. Wall space in particular is a big priority for the prints and projections.

Masley-Charlet: What interested you about the Guttenberg arts residency?

Smolarz: I was fascinated by the structure of the town of Guttenberg, New Jersey, where the residency is located, which is only four blocks wide and with a population of about twelve thousand. Guttenberg is one of the most densely populated places in the United States. As the name already suggests, there is a German connection in the history of the town, which was named for Johannes Gutenberg. Today it is home to a large South American population.

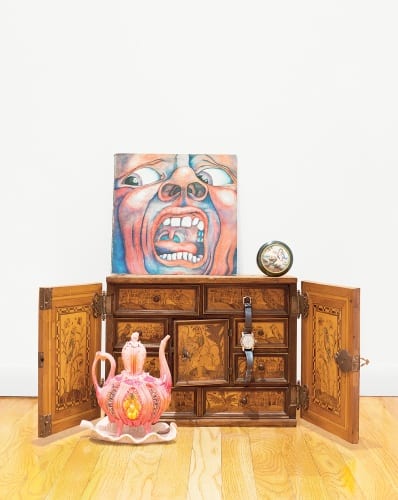

For me, it was the perfect place to continue my work on the photography series The Encyclopedia of Things, which started in 2014 when I collaborated with the Guttenberg community during my residency. The series, which is based on a very intimate process of constructing a portrait based on the individual’s most important objects, is also an object-based ancestral archive. There are objects from the 1964 World’s Fair, miniature chairs from the eighteenth century, and rings that have been passed down from mothers to daughters for centuries. It’s some sort of personal archive of Europe and South and North America in one small town in New Jersey.

Masley-Charlet: What has changed in your process since you’ve been there?

Smolarz: The former ceramic studio director introduced me to the practice after one of my photographs inspired me to venture out into 3D. Having direct access to the facilities and someone to guide you through the process of production was such a wonderful experience, since it’s a much more complicated process to learn new skills after graduation.

Personally, working with ceramics has been an adventure of making new works without consequences, and I am very grateful to have been given the time and space to experiment with a new process of art production. After the residency I continued to work with ceramics, and the piece Thank You for Everything Mrs. Lacks for the 2016 Art in Odd Places was the result of that.

Masley-Charlet: How do you sustain your art practice?

Smolarz: Financially, I sustain my practice mostly through freelance work, teaching, and occasionally making art sales. Since I freelance, work is very unpredictable and artist residencies are a great way to set time aside to focus on my work for a month or two. It’s very important for my practice and my sanity to keep some sort of creative rigor. I try as best I can to keep a schedule of at least three days a week for my art practice.

Of course, the schedule gets constantly messed up because of the irregularity of the freelance gigs. In some cases months go by where I spend almost no time in my studio, which is incredibly frustrating. Such is the price of flexibility.

Masley-Charlet: What is it you do for work, and do you consider this a part of your practice?

Smolarz: Pedagogy is a big part of my practice in that depending on the class I am teaching, I am introducing new theory every semester and have to be up-to-date on software when teaching a lab class. All the preparation for classes relates to my practice in one way or another, and it is absolutely inspiring to see how my students think about the world and the future they imagine for themselves.

Masley-Charlet: What about sustaining the creative part of your practice? How has it developed in the years since you graduated?

Smolarz: Over the years I naturally built a wide network of artist friends with whom I am in constant exchange, which leads to a lot of cross-pollination and inspiration. In addition to studio visits, we see shows as well as read and discuss books together. It’s been a very organic development. But the studio visits are what I gain the most from in direct feedback and critique that pushes me to further develop my work.

Masley-Charlet: Is access to visiting critics important because of the potential for exhibitions, need for artistic/academic dialogue, or something else?

Smolarz: A critic, a curator, and an artist have different approaches to artistic practice, and thus will be able to contextualize different parts of a body of work. For me they are equally important, although the most productive studio visits I have had are with artists who are also curators, since they are able to do the 360 degrees of production and presentation.

Masley-Charlet: What is the importance of an artistic community for you and has it changed over the years?

Smolarz: Having an artistic community means being in a constant exchange of discourse and support between the various members of the community, and it plays an important role in my everyday life as an artist. I have studio visits with other artists on a monthly basis; some of them have followed the progress of a project from the beginning, and their input is invaluable.

I have been invited to media and performance critics’ groups, and I am currently part of one. We get together every five weeks for very productive meetings. The group is very small and rigorous. There is actually quite a bit of pressure to present every five weeks, but the critiques are very constructive due to the intimacy of the group.

Masley-Charlet: How could Guttenberg Arts or artist residencies more generally support more experimentation? Specifically, do you feel like it is a safe place to fail? Can we talk about failure?

Smolarz: Experimentation is a big part of my practice as I constantly try out new directions, many of which lead to nowhere. I just shelved a project about fire, but to be honest, I am 100 percent sure I will revisit it. I am just unable to move forward at the moment.

That said, artistic production goes hand-in-hand with experimentation, and I would say residencies already support that by giving artists the time and space to make work.

Caitlin Masley-Charlet is a Brooklyn-based visual artist working in drawing, installation, and sculpture, and the deputy director of Guttenberg Arts in Guttenberg, New Jersey. She holds an MFA from the University of Arizona and an MS in design and urban ecology from Parsons/The New School. Her work has been exhibited in group shows at MoMA/PS1, Long Island City, New York; Center for Built Environment, Berkeley, California; and Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York. She has had site-specific solo exhibitions at McColl Center for Contemporary Art, Charlotte, North Carolina; Islip Museum, East Islip, New York; Urban Institute of Contemporary Art, Grand Rapids, Michigan; HVcc Foundation, Troy, New York; Kingston Museum of Contemporary Art, Kingston, New York; and the HDLU Museum, Zagreb, Croatia. Masley-Charlet is also the founder of studioMAPstudioSWAP, which is part of the Parsons/DESIS Lab/CSI Incubator program.

Immigrating from Poland to Germany, Elisabeth Smolarz grew up on the cusp of two different cultures affected by a communist and democratic system. Consequently, she became involved in the idea of how consciousness and perception is formed by one’s surroundings. Since then, her work has been showed nationally and internationally, in venues such as Lishui Biennial Photography Festival, The Bronx Museum, New York, Eyebeam Art + Technology Center, New York, Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw, Baden Württembergischer Kunstverein, Photography Triennial Esslingen, Carnegie Mellon, Independent Museum of Contemporary Art (IMCA) Cyprus, Reykjavik Photography Museum, Espai d’art contemporani de Castelló, Center for Contemporary Arts Prague, the Sculpture Center, New York, and the 3rd Moscow Biennale, among others. Awards and residencies include the LMCC Work Space Residency, New York, AIM Artist Residency, Bronx Museum, Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen Travel Grant, Karin Abt-Straubinger Stiftung Grant, Sarai Artist Residency, New Delhi, India, Capacete Artist Residency, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, LMCC Swing Space Residency, Red Gate Gallery Artist Residency, Beijing, China and more. Smolarz received her BA and her MFA from the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste Stuttgart. She lives and works in Queens, New York.