David Wojnarowicz was thrust into the national spotlight in 1989 when the National Endowment for the Arts rescinded its financial support for the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, curated by Nan Goldin for Artists Space. I described David’s controversial contribution, the essay “Post Cards from America: X-Rays from Hell,” as “a powerful harangue, mixing sorrow, indignation, fatigue and reverie” in my 1992 book Arresting Images: Impolitic Art and Uncivil Actions.

As part of my research on the escalating culture wars, I interviewed David at his loft above the former Yiddish Art Theater, a building which has subsequently been revamped into the Village East Cinema, on Second Avenue in Manhattan. It was a chilly New Year’s Day, 1990.

David had cancelled appointments with me twice because of the effects of his HIV infection and the drugs he was taking to combat it. He was thirty-five at the time and would die two years later from AIDS. David called early that morning and said he was feeling stronger and would be keen to speak to me if I could hurry over. I jumped at the opportunity.

David Wojnarowicz looked like a very tall, gaunt, and gawky teenager, but his booming bass voice was laced with anger and resolve. My questions prompted lengthy emotional responses; David did most of the talking. His fury against the NEA, pusillanimous administrators, politicians, the art world, and the Catholic Church was undisguised.

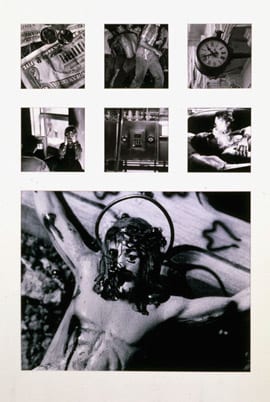

The recent controversy that broke over Wojnarowicz’s video A Fire in My Belly (1986–87), included in Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture at the National Portrait Gallery, compelled me to retrieve the cassettes of our two-and-a-half-hour interview from storage. What follows is an edited version of that conversation. David’s passion comes through loud and clear, some two decades later.

—Steven Dubin

Interview with David Wojnarowicz

Steven Dubin: Tell me about your art work, in the past and now, and is there a difference?

David Wojnarowicz: I’ve been drawing and making things since I was a kid, with some encouragement. I got accepted into an art high school and I met one good teacher, but the rest of them destroyed my work every chance they got.

Dubin: Literally?

Wojnarowicz: Literally. Dumped it in closets, threw it in trashcans, broke it. I was constructing 3-D tenements out of cardboard and paint, filled with long-hair radicals with Molotov cocktails and Black Panthers leaning out of windows, shooting farm animals in police uniforms. Power was given over to the people who took up arms as opposed to what was actually happening in the country, which was shooting at people in Kent State, murdering of Black Panthers, etc., etc. So I was making these things, and literally every time I turned around, this stuff would get destroyed.

Dubin: So in ’68, you were fourteen.

Wojnarowicz: I was hustling in Times Square and at times living in different boroughs, and people would pick me up or I’d stay with guys I knew who were also hustling in the street. It was a very erratic life. I spent enough time in school to hang on in terms of grades; I rarely studied what I was supposed to study. I was asked to do a book report on an ethnic group, and I’d do one on the Black Panthers and fight the teachers all the way when they’d try to explain that that wasn’t what they had in mind. I attended demonstrations. As a kid, I witnessed some of the first responses to the Viet Nam War; I remember turning a corner and seeing a small group of people with long hair, which was unusual to see then uptown, holding plastic dolls that had been torched and covered with red paint like blood, and signs against the Viet Nam War, and construction workers running down the street beating the shit out of them. Witnessing scenes like that and always being upset by the balance of power and all these scrawny little hippies and these gorillas in construction gear that basically were killing these people, smashing their heads against sidewalks. I didn’t know much about the war; I didn’t really know much about what was going on in politics. It translated into certain activities when I got in touch with kids who were more educated about what was happening. So I’d end up at Black Panther demonstrations, sometimes violent ones, unprovoked things—and something would just tick a cop off and all of a sudden they’d be running around with the guns and smashing things. I gave up work and was on the streets, came close to dying on the streets, mostly from lack of heath care, lack of food, lack of sleep.

Dubin: How many years are we talking about?

Wojnarowicz: A two- or three-year period on the streets that was the most damaging. By that time I hit seventeen or eighteen when I first came to the halfway house for a year, went back onto the streets for a year, came back and extricated myself from that repetition; managed to get a job, etc. I started writing, and it was the only way I could communicate: I couldn’t relate to anything in terms of conversation with people: I found I had such an enormous store of experience I couldn’t begin to touch with anybody, because of the possibility of rejection, and because the other people I worked with, aspiring dancers or actors, came from privilege. It took a long time before I could even begin to talk to any of them. Anyway, I made it through that and met a couple of people who encouraged me in terms of writing and drawing. Finally, in 1978 I went to live in Europe for the rest of my life, which lasted about a year, and then came back and started working in a rock-and-roll club. I formed a band with a bunch of people called 3 Teens Kill 4, which was a New York Post headline. I always resist getting to know something in terms of machines or operations, just learning to turn it on and go from there on my own. Part of it is resistance to manuals of any sort. I remember thinking that those are the people who rule the country, the people who can figure out the manuals. Same thing with photography. I never learned anything about aperture settings or speed of film, I just do it to pull something out of it.

Dubin: I was thinking about how when you talked about not being able to communicate with people, how easy it seems to talk now to go from that to doing public performances.

Wojnarowicz: My twenties were miserable . . . getting off the streets. The communication was really difficult. It started getting better by the time I hit twenty-four, then it got stronger and stronger, or at least I trusted myself more and more. I hit a point that was very confrontational for me. One of my best friends was dying, and I was surrounded by various groups of people—some people were doing extremely dark stuff in terms of film and performance (and most of them became IV drug users); some groups were politically sophisticated; other people were artists who were making careers out of what they did and being wildly successful. I was surrounded by these different ways of dealing with things. I could see what each group of people felt, and I could understand it all, but I think I was confused, given I was dealing with mortality. Seeing these politically correct art types who are fashioning incredible careers but who would never say a thing about AIDS or what the government and organized religion were doing. I was angry and I ended up isolating myself.

Dubin: Before ’87 was your work political?

Wojnarowicz: I always feel uncomfortable when somebody says my work is political—I have a knee-jerk reaction to that. I used to do stencil work in the street before I started showing in galleries.

Dubin: What was the nature of the stencil?

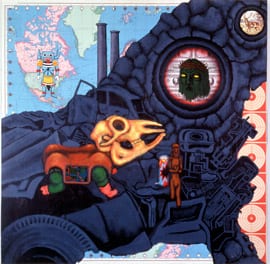

Wojnarowicz: They were burning buildings. For the band we started, Julie Hair and I were making spray-painted posters, whenever we were going to play a date. She had a box of these international symbols—benign symbols of car crossing, train crossing, male, female, no smoking. So we thought, let’s invent some symbols that are international but that haven’t been invented: a burning house, a stencil of a human head with a target in the center of the face, little army men with machine guns, recoiling figures, bomber planes, explosions, things like that, an image of the United States with an explosion coming out, and a little businessman with his hat and briefcase falling. I started doing them on posters, and then rival bands ripped them down, so we started doing them on abandoned buildings. I lived on the Bowery downtown where there are auto accidents, and these cars would just sit there for nine months or a year and slowly be picked apart for pieces. Given it wasn’t a neighborhood full of rich people, they never bothered to tow these things, so I had this idea to start stenciling these enormous war panoramas all over the broken windshields and on the tires. Somebody was curating a show and asked a friend if he knew who was doing these stencils, and that was my introduction to the gallery system. They asked me if I had any paintings and I had some little spray paintings, things on paper, but they wanted big paintings, so in a weekend I did my first big painting. That was my entrance to the art world. I was in a group show that was in a horrendous Soho gallery; I was naive and didn’t know anything about the various levels of galleries. They asked me to do a one-person show about three months after this first group show, so I said OK and I worked all summer. One painting was a group of red naked boys, teenagers in some desert landscape armed with rifles to protect themselves, doing every sexual activity you can think of, and other boys standing guard. The second panel was a big explosion of what I saw at that time were symbols of Western civilization, with a young boy running through it all. They were completely horrified when it came in the door. If I think back, it was pretty good.

Dubin: What was the outcome in terms of the reaction from the gallery?

Wojnarowicz: Absolutely nothing. Well, nothing in terms of the art world. They wouldn’t touch it with a stick.

Dubin: I was going to ask you about the parallels about someone starting out on the street and being brought into a more legitimate system.

Wojnarowicz: There were a number of people doing stuff in the street. There was Keith Haring, [Jean-Michel] Basquiat; later I came to see that some of the things I’d seen were by Jenny Holzer, and all this was happening about a year before I was approached by anybody about showing. I showed in a few group shows. I was attracted by the forum of doing stuff in the street, attracted by the democratic nature. I’d be doing in the warehouses along the river by myself, running around in these warehouses which were such beautiful and intense spaces; there’s something very attractive about architecture that’s in decline and especially architecture—industrial architecture—that represents hope for the future, and suddenly it’s dying. There’s something really compelling about it. I would use these rooms like a big canvas and spray-paint sentences or texts or sometimes images on the walls. So I was doing things on the street before I came into contact with some of those other people that came from a different intention but weren’t that dissimilar in terms of the final forms. I got excited about seeing it move away from the river, these isolated places where very few people would go into, to just streets all over the place. Before I got into the art world, I was doing all these action installations, which is what we called them. Nice words for illegal installation. We did one where we went into a staircase at one in the afternoon on a Saturday when it was crowded with art types and in a minute spray-painted a plate, a knife, and a fork, and above that a burning house, and above that bomber planes and people trying to protect themselves, and then we dumped about one or two hundred pounds of bloody cow bones from the meat market district leading up to this image of this plate and then left. We got away with it. I love the idea of spontaneous things, things that you witness without knowing you’re witnessing it. Stepping through a doorway to a gallery really didn’t excite me so much. Instead of the usual exporting of dictatorship, I was trying to get a group of people together and a group of props together and have people arrive at different times together at a specific point like inside Macy’s and set up a firing squad, have blood sacks and have these people shoot somebody. Just suddenly do this abruptly in a department store or a furniture shop and have someone like myself document the ensuing reaction and then everybody would just disappear in their own different directions. We never got to do that. A lot of people talked us out of it, given the nature of the New York City Police Department. There was a whole series of things I was planning or dreamed about doing and never did. Part of it was entering into the art world and using that area as a point of letting this information out, letting these images out. It was pretty crude. I didn’t really have experience.

Dubin: How would you characterize your relationship to the art world now?

Wojnarowicz: Very complicated. I’m isolated from it. I show in it at times. I live on it. Paying my rent, buying food, paying for medicine, as much as possible. In terms of things like censorship, the art world is a total joke. There are some decent people in it, but the majority of people who are in the more powerful institutions (galleries and museums), most of them could give a shit about civil rights, could give a shit about the First Amendment. I know bottom line that if things were to get repressive enough that the only art they were allowed to sell were things like refrigerators, they’d be just as happy to sell a refrigerator as long as they could command half a million dollars for it. They do benefits for various things, whether it’s relocating refugees in El Salvador or raising a little bit of money for AMFAR to fight AIDS, but in terms of having to fight something 100 percent, in terms of the issues of civil rights, they really don’t care. They have a product to sell. People will posture to the press on a certain level, and when really pressed to define themselves or to make a move or to act in a certain way to protect what they’re fighting for, publicly they’ll posture and bluff, and that will be it. And that’s what I experienced at Artists Space. What a fabulous PR job in terms of the media.

Dubin: Were you involved with the various meetings with [NEA Chair John] Frohnmayer and so on as they occurred?

Wojnarowicz: Not early on. Early on I was kept in darkness. I feel I was manipulated in terms of what people would say to me privately and in terms of what they did with the media.

Dubin: Are you saying that certain people were covering their own asses?

Wojnarowicz: Most of them. Like with Frohnmayer. The first time I met him, I couldn’t even believe they let me. I was told right off, “You can come to this meeting but you can’t be confrontational.” I said not to worry, I knew how to restrain myself, but really, if I was going to be confrontational, I’d be confrontational. Nobody was going to dictate to me. Which was the bottom line with that whole controversy. I pick up the paper and I see [US Senator Jesse] Helms having a media orgasm over the First Amendment having just been trampled so severely. Saying that he enjoyed this a lot more than he enjoyed the Mapplethorpe thing, and here’s Artists Space saying, “We’re not a civil libertarian organization. We’re just an artists’ institution.” The gist I got from them was my asking them to represent what I consider my civil rights made me some kind of extreme radical. Angry.

Dubin: What’s interesting· there—at least in the media coverage, you wouldn’t have a sense of there being a conflict between you and Artists Space because what was portrayed was an organization that was defending “their artist.”

Wojnarowicz: They were savvy enough not to cancel this thing. I sent the essay down, and I get a phone call: “You have to change this.” Now they’re saying they didn’t do that, which is completely bullshit. Nan [Goldin] said she was curating a show dealing with AIDS among her friends, which I thought sounded beautiful. I’d be glad to be a part of whatever Nan does from now till the end of the next century. We talked about looking at how this disease was dealt with by a group of people who had died from it, and other people who had watched them die. Given who my friends are, it’s like these threads that come together. She asked me to put some work into this show, and I said sure. She asked me if I’d be interested in writing one of four essays. I said sure.

Dubin: How long did it take you to write that essay? The one in the catalogue?

Wojnarowicz: About a day.

Dubin: Is it essentially the way you wrote it?

Wojnarowicz: When I write—and this has a lot to do with the way that I work in any media—I rarely do second drafts. I’ll do a second draft just to clean up typos and maybe a little shift in the structure, but I’ve always been attracted to the way that people who don’t know how to draw, draw. Their energy’s so direct between the pencil and the paper and it’s not cluttered with bullshit style. I feel the more drafts you put writing through, the more you repainted the same painting, all the blood was taken out. It no longer had life in it. Anyway, I wrote this thing really fast. What I end up writing about is what I obsess about.

Dubin: Was any editing done in terms of Nan or anyone at Artists Space?

Wojnarowicz: Nan read it, loved it, and said thank you. Then, in a conversation later she said Artists Space was talking to their lawyers to see if they could publish it. I said “What?” She said it’s probably just talk. So I waited and then I get a call from [director] Susan Wyatt asking me to change it. It was the first time I’d been confronted like that in almost nine years. People hated my work or liked it, but I never had anybody tell me to change it.

Dubin: Specific suggestions?

Wojnarowicz: We never got that far because I just said “No.” She wanted to know what the repercussions of this were, and at that time I found out it was an NEA-funded show. “Oh? Well good.” She asked me if I would put in disclaimers within the paragraphs of writing and I said, “No, of course not.”

Dubin: Disclaimers in terms of what?

Wojnarowicz: We didn’t get that far again. I just said “no.” Her lawyer said we couldn’t possibly print some of the stuff I had written. I said I was going to talk to someone and ended up calling the Center for Constitutional Rights. They said there was one area in the essay that could bring a lawsuit and the weight would be on me to prove what I’d written.

Dubin: In relation to what?

Wojnarowicz: Because I tried to clearly call it the way I saw it and not pull punches. Not be polite about it. The thing I find myself very resistant to is not so much that people practice religion but that a man in the “house of worship” can do something that can affect my life, that can deny me. If you look at what this government has done, in the last few years, they prosecute certain spiritual worship that denies medicine; the government prosecutes people who practice that spiritual belief when they deny medicine to their children or to family members that would heal them. The government prosecutes them. If you look at safer-sex information, it can almost always stop the transmission of a disease. If you look at information as preventative medicine, the church has been persistently behind the scenes to stop that information. The Board of Education AIDS Advisory Commission is taking federal, state, and city money, but they only teach abstinence, refusing to give school kids a half an hour talk that might save their lives.

People still believe this disease has a moral connotation, that it stays within large urban centers, but planes, trains, automobiles crisis-cross this country. It’s everywhere. It’s accelerating in country and towns, among teenagers. Teenagers in New York, one in one hundred are HIV-positive. One in four people in the Bronx are HIV-positive. They still think it’s a homosexual disease; they still act as if only wild people get it. This is what I see as a sign of fascism: to let people die, help people die, because you don’t agree with them on a spiritual level.

Dubin: Given what you’ve just said, did it surprise you that there was this reaction to your essay? You obviously were stepping on toes.

Wojnarowicz: I’ve been writing this kind of stuff for years, and bottom line, it was a few government coins—I should say public coins but obviously the public doesn’t determine where the money goes—pennies, connected to a bunch of writing. The only difference between this piece of writing and other writings I’ve done is that it named names. I have a painting in a show with very real politicians saying very real statements: “You want to stop AIDS, shoot the queers,” “If I had a dollar, I’d give it to an innocent victim not some person with AIDS.” These are very real things in real newspapers but there’s not a problem because there’s no names named.

Dubin: Did anyone ever say “Look, take the names out, it will be easier for everyone”? Or was that implied?

Wojnarowicz: Nothing specific was implied other than being asked to change it; I said I wouldn’t. Then they [Artists Space] said they were going to change the funding to the Mapplethorpe Foundation; I thought well, the catalogue would say “funded by the NEA/Mapplethorpe Foundation” and I thought “what a perfect marriage.” It turned out the show was funded by the NEA and the catalogue was funded by the Mapplethorpe Foundation. Meanwhile, Artists Space had brought it to Frohnmayer’s attention, had gone down there with this essay, although later they tried to backtrack and say it was just part of general interaction they’ve had with Frohnmayer from the beginning. Behind the scenes, he was asking for a return of funding for the show, and Artists Space was saying “No”; again, they don’t want to look like the Corcoran [which cancelled Robert Mapplethorpe’s retrospective The Perfect Moment], so to a certain extent they resisted. It was a Friday night almost a week before the opening of the show, and it already had been flying around the press and I said “Susan [Wyatt], what exactly are you going to do? What exactly is the board of Artists Space going to do? Just tell me.” At that point I’d been told that Frohnmayer had been jumping off the “it’s too political” quote to “the P word doesn’t mean the same thing in Oregon as it does in Washington.” I confronted Susan and said, “You’re giving this guy all the room in the world to save face from jumping from one position to another until he comes up with one that’s successful. Why are you waiting?” She said “Well, I’m sorry but we don’t want to risk losing our funding and we’re not going to fight this in court.”

Dubin: You used the word “invisibility.” It seemed to me that one of the themes in your essay was the distinction between “private” and “public,” making ideas public so people won’t be invisible, people can’t deny them. That seems to me to be a very strong theme throughout.

Wojnarowicz: I’ve always had this impulse, it’s part of my character, to put my face in something and to know what it is rather than turn away from it. I tried to explain that on certain levels, why should I keep it private? People who have sexual desires are killed, murdered, beaten, stabbed, raped. We have people preaching from pulpits, the same pulpits that were used during the Viet Nam War, preaching for blood lust. It’s at least implicit in what they preach that it’s OK to be violent against people of our sexual orientation. Every time you go on the streets, there’s a million ads about men and women kissing each other. I am invisible. Why wouldn’t I speak about it? You’re not going to speak about it. The government’s not going to speak about it. The church isn’t going to speak about it. Any public representative isn’t going to touch it. It seems hard for certain people to understand what that must be like; they’ve never had an indication of what it feels like. I would just ask people, if legislation were reversed and their heterosexual orientation were suddenly outlawed and forbidden and despised, what would they do?

Dubin: What’s happened to you since this whole thing broke? I know that it accelerated Serrano’s and Mapplethorpe’s careers. Have people been seeking you out for interviews?

Wojnarowicz: There’s never been a response. What would be “career moves” for other people has never accelerated anything like sales for me. It’s just the nature of what I do. There’s something that scares people off—most collectors are investors. There was a point in ’84 when I was at the Whitney, which was very emotional for me to have certain kinds of recognition. That opened up doors left and right, and people just wanted anything with my name on it. It was unsettling, disturbing, confusing stuff.

Dubin: Do you have any sense of where things are going?

Wojnarowicz: This country has infused the things falling apart with moral symbols. If you’re homeless, it’s your fault, you chose to be that way. If you’re poverty stricken, you chose to be that way. If you have AIDS, it’s your fault, you chose to be that way. I end up feeling I’m in a nation of zombies.

Steven Dubin is Professor of Arts Administration at Teachers College—Columbia University. His areas of interest include censorship, controversial and transgressive art, and museums. Two of his books chronicled the “culture wars” of the 1990s: Arresting Images: Impolitic Art and Uncivil Actions (1992) and Displays of Power: Memory and Amnesia in the American Museum (1999). For the past decade he has focused on the art and politics of South Africa; his Mounting Queen Victoria: Curating Cultural Change (2009) examines the post-apartheid transformation of museum exhibition and collection policies, staffs, and visitors.