As a man of European and African descent from Venezuela, my experience of racism, and the particular artistic and epistemic exclusions that come with it, is most directly inflected by my personal background: I was born and educated in the Global South and immigrated to the United States in 2012 at the age of forty-nine. I conceive of curatorial practice as an invitation to think about and question how we relate to art. The key for me is to recover and reinterpret the difference between the reception of art in the metropolis and in situations at the margins, such as those that prevail in Latin America, a difference that has not been properly articulated from the perspective of canonical art history. Today museums and institutions in the West are still reckoning with how to overcome the structural discrimination that is at the foundation of the art system. The collection or exhibition of works by women and artists of color has been the exception and not the rule; only the latter would confirm an actual commitment to inclusivity.

In 2019, when I took up my position at the University of Florida’s University Galleries (UG), I was acutely aware that I was inheriting an institutional framework that too often shored up white privilege at the expense of histories that include the contributions of people of color, as well as those of different genders, nationalities, sexual orientations, and classes. Given this context, I remain steadfastly committed to what has been my lifelong ambition since beginning my work as a curator in 1989: to showcase excellence in the arts, with an eye to a more equitable and just future both within and beyond the gallery walls.1 To this end, UG launches its fall program with the exhibition In, Of, From: Experiments in Sound, which explores new ways of understanding the relationship between art, politics, and new media and includes installations by Nikita Gale, Jules Gimbrone, Cecilia López, and Thessia Machado. In an interview conducted on June 28, 2020, I invited Gale, in advance of the exhibition’s opening, to discuss the work that will be presented and how it resonates with our present moment and our solidarity with Black Lives Matter.

—Jesús Fuenmayor

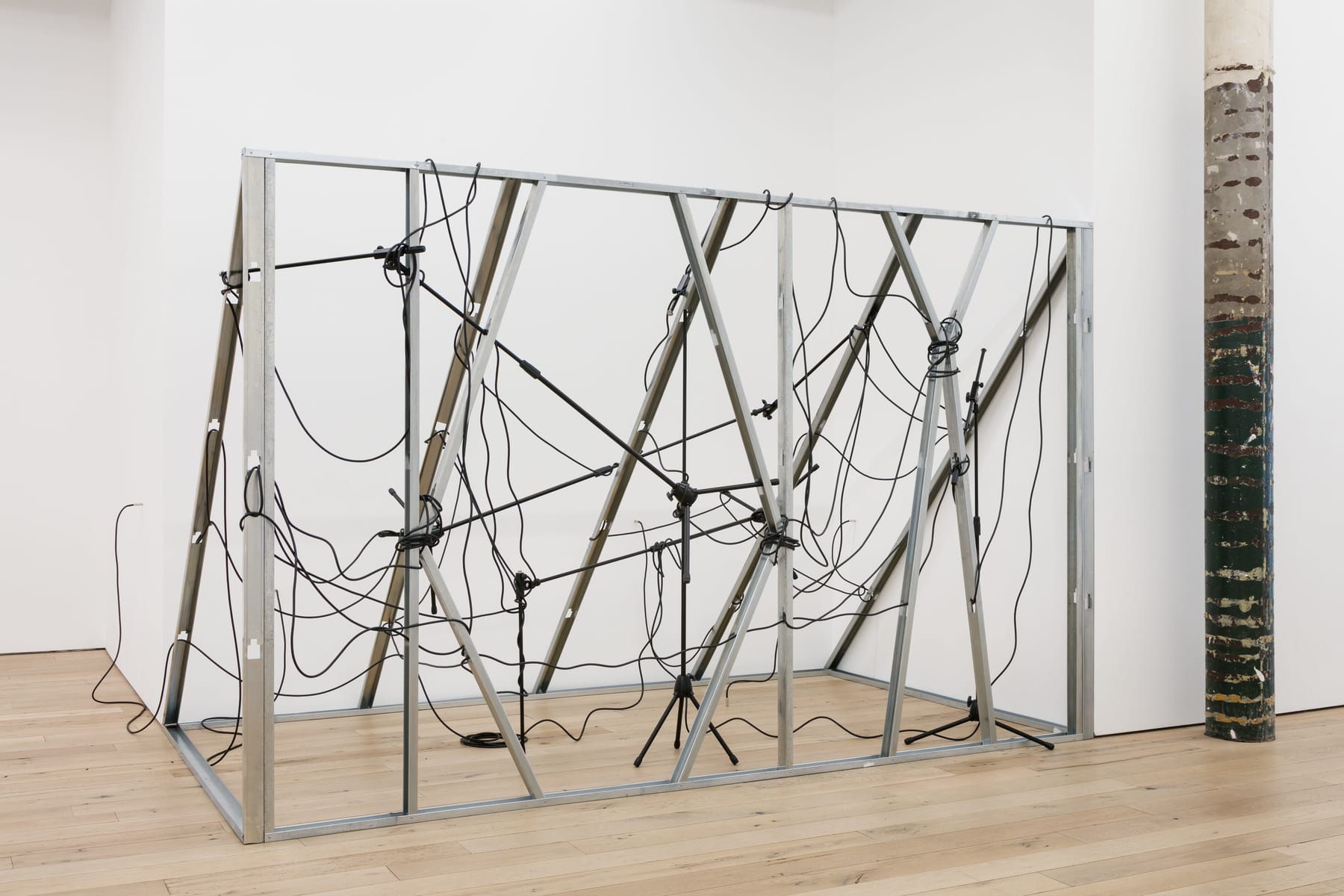

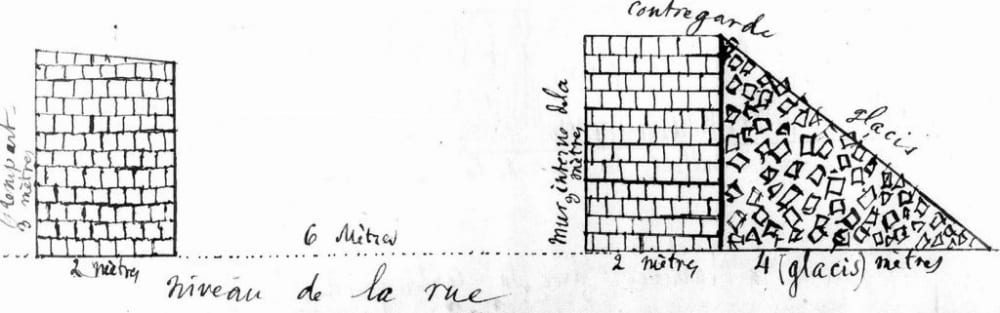

Jesús Fuenmayor: As part of the University Gallery fall exhibition In, Of, From: Experiments in Sound, we are including your installation INTERCEPTOR (2019–20). It is a work that adds a complex dimension to the idea of experimenting with sound. INTERCEPTOR departs from a nineteenth-century barricade design (based on an “ideal barricade” construction by Louis-Auguste Blanqui from his Manual for an Armed Insurrection, 1866). The work’s relation to sound is visual or metaphoric, because it is a soundless piece. Could you please describe the work and the ideas that motivated you to produce it?

Nikita Gale: In thinking about the infrastructure of crowd control, I became interested in the ubiquity of barricades at protests and other large public gatherings like concerts and political rallies. Barricades have origins in a very radical material tradition, having been made out of refuse by the working classes in nineteenth-century France to block and redirect the flow of street traffic as a means of protecting themselves against state violence. These structures also served as social spaces and ad hoc stages for these citizen insurgents to address one another. Through the advent of mass production and appropriation, barricades have now become a mobile architecture that controls how crowds and audiences are allowed to take up space; they are no longer technologies of “the people” but are now technologies of authority. The freedom to speak and to listen is negated by the physical control rendered by barricades’ presence.

INTERCEPTOR considers exclusion and protection, radical expression, and how the regulation of space influences the regulation of speech and listening.

Fuenmayor: Some art professionals may remember that Michael Asher, one of the central figures of institutional critique in this country, once produced an installation using the same type of construction materials that you use for INTERCEPTOR. I am referring to Asher’s intervention at the Santa Monica Museum of Art [now the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles] in 2008, in which he—by consulting exhibition design plans and diagrams—rebuilt every temporary wall that had been constructed since the museum’s move to its new location in 1998. Rather than actual walls, he used metal or wooden studs to create a sort of “skeleton map” of the institution’s exhibition history. The similarity with Asher’s installation and INTERCEPTOR could be merely coincidental, but I find it extremely compelling as a way of understanding your work and how it points to how “institutional critique” is not politically and socially engaged enough. Could you elaborate on how you think this piece, or the legacy of institutional critique, relates to your work and new experiences in contemporary art?

Gale: If I’m going to think through my relationship to the work of Michael Asher, I would think about that particular work through the processes of inversion and compression or accumulation. By this I am referring to the ways in which, through Asher’s compression of time in this piece—by placing into one space all of the studs for temporary walls for exhibitions mounted over the course of a decade—he creates an inversion of the use of the wall. The wall stud as support and foundation suddenly becomes porous, and also prohibitive to delineating a space that can be occupied by the viewer.

With INTERCEPTOR, these processes of inversion and compression are also at play, but in pretty different ways. I am interested in the stud as a ubiquitous material that is used in wall construction. Walls are architectural features that simultaneously define space and support artworks, as surfaces for projections or for hanging and framing artworks; in this way the wall shares a common use or objective with the barricade in its division of space, but it remains porous. In thinking about the significance of the music studio, particularly as a site of Black creative production, I find that the materials that are used in the transmission of sound, and for the support of tools of production and sound extraction, have an ambient presence that reflects the ambient quality of these foundational materials, like wall studs, in space. So through the process of inversion, INTERCEPTOR uses objects that facilitate the production of sound and space to inhibit both.

Fuenmayor: It is thought provoking that in this work you seem to be inverting the logic of “countervisuality,” one of the strategies that has been more commonly used to politicize artistic practices since the sixties. This work does not transmit any physical or real sound but evokes an imaginary sound: the sound of rebel multitudes. Because it speaks through silence, incorporating into its visual language a subversive undertone, I find it particularly meaningful in light of our current political context. Could you address INTERCEPTOR’s relation to this context and how that relationship may have shifted over time?

Gale: Well, I think the idea of silence is particularly meaningful in this moment, especially in thinking about how systems inflict silence as a form of authority. The shadow bans on social media, blocking hashtags, and blocking internet access in general are just a few of the political uses of silence and blocking for the purpose of disenfranchisement. But as a counter to its use by authority, silence is a very useful and radical tool of refusal. It can be threatening, and the sound theorist Michel Chion even suggests that when we encounter things that we expect to make sound but do not, it can often seem downright antagonistic and “diabolical.” I’m really into this idea of radical silence and what that actually suggests. We generally understand how an audio tool like an audio cable works: it carries a sound signal from a recording device (like a microphone) to a processing device (like an amplifier) and then to an output device (like a speaker). The cable itself is silent, but you understand that sound is being transmitted elsewhere even if it’s in a register to which you may not have access.

I think this is a political moment when this idea of register has been thrown into relief in a profound way. There is radical Black leadership that has been having conversations about racialized violence and systemic oppression for decades and centuries, and they will continue to have these conversations in registers that are not all that accessible for the majority of America, which is only recently trying to catch up. This brings me back to the significance of sound in the history of the Black experience in America, particularly slave spirituals and work songs, which were always coded with meanings only legible to the enslaved—the sounds of which, in the ears of the planter and slave driver, registered differently than they did in the ears of the Black slaves. Then from here, I start to get really excited about talking about the formulation of audiences, but that’s another conversation entirely!

Fuenmayor: One of my motivations for presenting In, Of, From: Experiments in Sound is to explore identity politics in the arts in a different light, in order to create a more productive and nuanced connection between artistic practices and the political issues of our times. How do you feel your work connects and/or creates bridges between the political and the arts?

Gale: The work implicates contemporary materials in historical processes of alienation, appropriation, control, and violence. A barricade is a wall is a slave code is a freeway is a predatory loan. And to quote Emma Amos, “It’s always been my contention that for me, a Black woman artist, to walk into the studio is a political act.”

Fuenmayor: I think it is important for the art community to engage questions that are often not considered relevant because of the way our relationships are governed by a preexisting set of power relations. Black Lives Matter and other initiatives are now being engaged by many different communities. Do you have any thoughts on how to address, in a critical and pertinent way, our current political debate in the art community?

Gale: LISTEN TO BLACK WOMXN.

Nikita Gale is a Los Angeles–based artist who holds a BA from Yale University and an MFA in new genres from the University of California, Los Angeles. Gale has exhibited at MoMA PS1, New York; Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE); the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; and the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, in Made in L.A. 2018. Gale’s work has been featured in Artforum, Art in America, Frieze, and the New York Times Style Magazine article “Works for the Now, by Queer Artists of Color.”

Jesús Fuenmayor is the program director and visiting curator of the University Galleries at the University of Florida.

- Given my personal and professional background, I am proud to have initiated my curatorial program at UF’s University Galleries with an exhibition of Roberto Obregón, an artist of Afro-Caribbean heritage, working-class origins, and a queer sensibility. The program also presented an exhibition by Brazilian artist Felipe Meres, which explored the way science deals with representations of different sexualities. More recently, we were invited by gallerist Andrea Rosen to participate, as one of the sites, in the Felix Gonzalez-Torres exhibition Untitled (Fortune Cookie Corner), in which the subtle metaphoricity of this Cuban American artist’s work was catalyzed as a way of reflecting on the current pandemic. In addition to In, Of, From: Experiments in Sound, the UG fall program includes an exhibition of two historical videos by Adrian Piper in the Gary R. Libby Gallery. ↩