Roberto Obregón was born in the coastal town of Barranquilla, Colombia, in 1946. He came to artistic maturity in Venezuela, where he moved with his family in 1954. He lived in Caracas, the capital, from 1966 to 1982, when he relocated to the small town of Tarma. He was of Afro-Caribbean heritage, of working-class origins, and of a queer sensibility (likely gay, though he never openly said so). While these biographical details may have informed Obregón’s artistic practice, such identifications are not illustrated in his work. Instead, as an artist he engaged in deliberate disidentifications with, and a tenacious resistance to, any stereotype or schema that might attempt to control the meaning of his life and art. Obregón harnessed his chosen primary material—rose petals—toward a careful meditation on time and nature while at once imbuing their collection and display with subtle ironies whose coded meanings often hinge on the difference between gestures of cultural alliance and acts of cultural appropriation and the power differentials each entails.

I first encountered Obregón’s work in 2012 (well before I partnered with curator Jesús Fuenmayor on the recent exhibition Accumulate, Classify, Preserve, Display: Roberto Obregón Archive from the Carolina and Fernando Eseverri Collection1). At that time, in a review for Artforum, I noted how “his assembly of real and watercolor rose petals recalls the seriality of some of the [São Paulo] biennial’s photographic work but is instead motivated by desire for a universal symbolism that could convey the precarity of life and communication itself. That part of the work is pink might trouble some critics, so closely does Obregón’s hue court (if ultimately abstaining from) kitschy effects.”2 Obregón’s flirtation with kitsch is shared with another artist I love, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, who elegantly indulged in creating displays of beaded curtains and used everyday materials with shiny surfaces, such as silver-wrapped candy. What is more, both artists were affected by the AIDS pandemic, confronted personal loss, and addressed how infection with HIV intensified stigma, discrimination, and denial.3

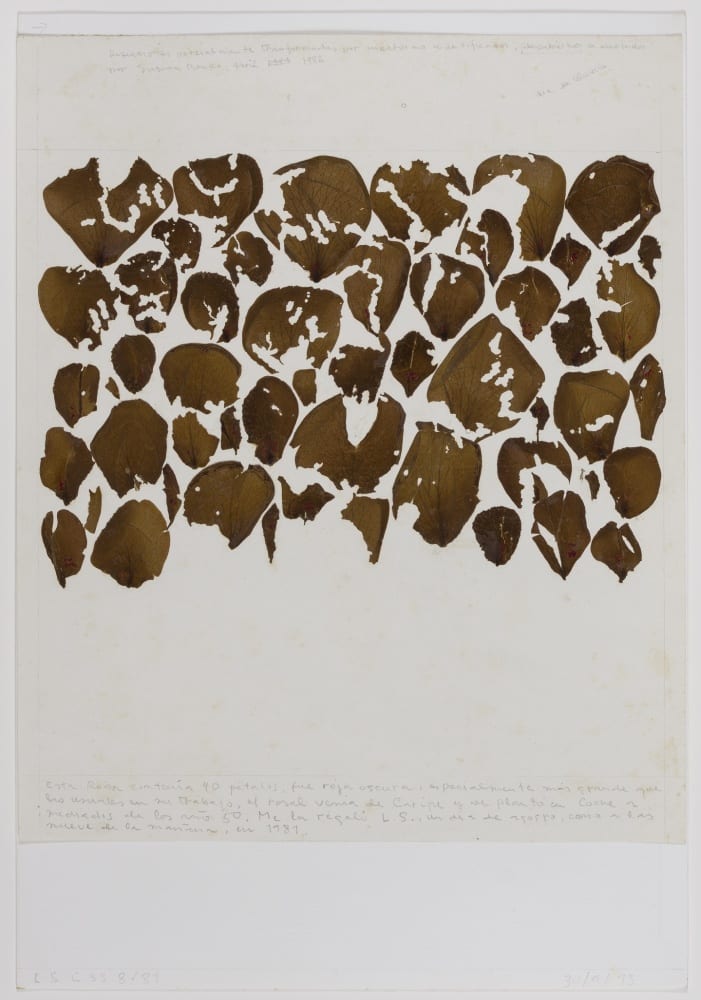

In the face of our current coronavirus pandemic, I would like to pause and think about Obregón’s Rosa enferma (Sick rose), which served as the promotional image for Accumulate, Classify, Preserve, Display, a series of documents and works to which I keep returning. On the paper on which the original forty petals of Rosa enferma / Disección real (Sick rose / Real dissection, 1981–82) are displayed, Obregón notes that the rose was a gift from L. S. (his friend Luis Salmerón). He also identifies the approximate date of the gift, among other details, including día de lluvia (rainy day), which is written diagonally in the upper margin above the composition, and how the petals were ultimately damaged by an unknown insect.4 The delicate closeness of the petals’ arrangement on the paper contrasts with the artist’s subsequent use of the grid, calling attention to how the latter identifies, isolates, archives. With Rosa enferma / Disección real the petals’ proximity and physical contiguity instead display a scene of what one might provocatively call “botanical intimacy.”

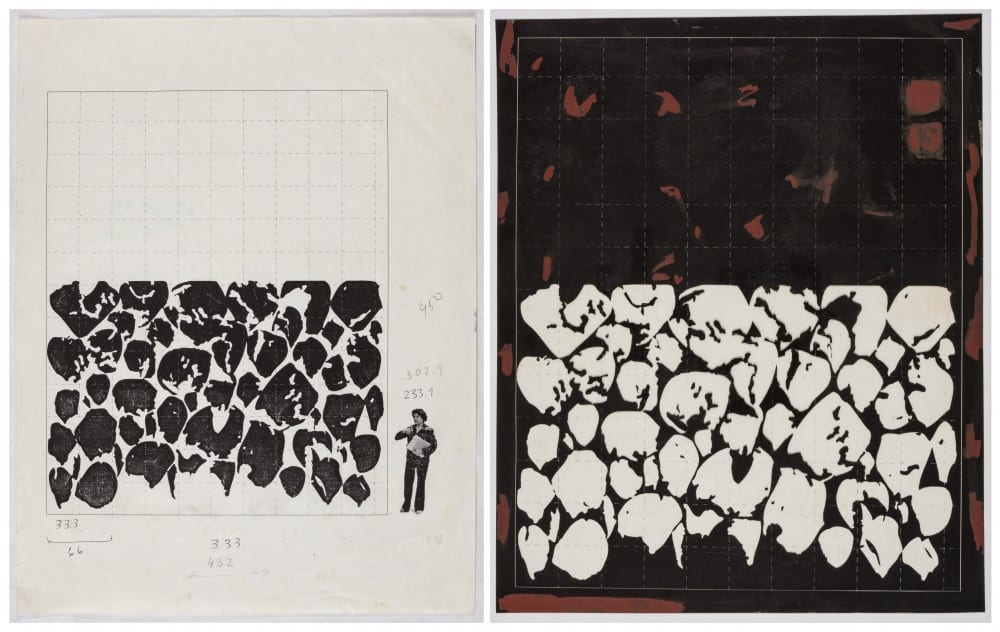

When opening the two drawers of the display cabinet dedicated to Rosa enferma in the exhibition, one noted how the original specimen as well as the petals’ subsequent reproductions at Obregón’s hands display irregular holes, uneven edges, fragments: bounded forms show perforations; contours have been penetrated. The archival documents bespeak a tension between the real (or imagined) regularity of the grid and the concerted asymmetries of Rosa enferma’s tattered and mournful forms—as if the grid could not contain or protect the rose from the sickness that befell it, dramatizing the petals’ demise. Accordingly, Rosa enferma presents less a pristine botanical specimen than a lesson in how the objectification of knowledge through classification can be infiltrated by what remains beyond the discursive and material frames (i.e., disease) associated with that objectification. As to the series title, it derives from an eponymous poem by William Blake, a poet of the romantic age who developed a poetry of complex symbolism and private myth. Given the external cause (i.e., foreign agent) that, in his own work, accelerated the petals’ decomposition, Obregón suggests that “Blake does not refer to the sick rose but [to] love as a sickness.”5

Obregón developed the scene of the dried petals’ vulnerability—or how roses, too, can become ill—across a range of techniques: drawing, photocopy, print, photography (all on display in the exhibition), and ultimately in a large-scale installation from 1993, for which the enlarged petal reproductions appeared as white silhouettes on a black background (see below). Between the gifting of the original rose and the final installation it inspired, Rosa enferma accrued additional meanings. Ten years after Salmerón presented Obregón with the dark red, fragrant rose from his mother’s garden, Salmerón died of AIDS. Though seeming to evoke the loss of his friend in both title and composition, as a work Rosa enferma’s final form was in fact the result of an oversight: Obregón forgot to use alcohol when dissecting the rose and preserving its petals on March 27, 1981.6 For Obregón to call the work an homage would have been too literal and especially anachronistic, even though the petals’ initial contiguous arrangement—evident especially in how he emphasized their delicate membrane-like translucency—may evoke memories and intimacies of a different order. As an homage the work would have been a bit too saccharine and contrived, given the sentimentality that the image of the rose has accumulated over time, a sentimentality that responds more to societal conventions over loss than to the singularity of an individual’s grief. Reflecting on his friend’s passing, Obregón observed, “That day the rose he had given me took on another connotation, it became a true allegory.”7

Rosa enferma is not a transcendent work of art, but its meaning transcends the archival and curatorial functions of accumulation and preservation. In Obregón’s real dissection the petals were exposed to something that came from the outside and changed the nature of their subsequent display, classification, and reproduction. The flower’s veins, which create an expansive cellular network of lines, remain visible in the dried petal tissue, as do the paths bored by the unidentified insect to which the petals were not immune. On account of the contingencies that prevented their unspoiled preservation, what survives in these forty petals are the traces of a common corporeality; that is, a shared vulnerability that cuts across the plant and animal kingdoms.8 Organic bodies experience birth, growth, development, and death. At each stage they are permeable to external factors, to infection and communicable disease.

As I write this short text while sheltering at home and social distancing, Obregón’s Rosa enferma repeatedly reminds me of this common corporeality and how we daily negotiate our bodily vulnerability. To recognize this shared vulnerability is to cut across distinctions such as self/other, inside/outside, and is at once to acknowledge how the imagined boundaries of the body and self are porous. Accordingly, we are tasked with rethinking modes of relationality: how caring for oneself is, somewhat paradoxically, to care beyond oneself, for community.9 But our daily choices in the interest of remaining healthy—keeping our vulnerability at bay—in the face of the pandemic (e.g., to wash one’s hands for twenty seconds; to use hand sanitizer; to wear or not to wear a mask; to go grocery shopping or to ask for food delivery) fail to deflect the coronavirus’s differential impact on specific demographics, largely defined by age, class, and race.10

Rosa enferma speaks to our shared vulnerability and how it enables care and love. We reach out to family and community, even former friends and ex-lovers, in a way that is possibly sentimental and in tension with Obregón’s allegorical understanding of his work, even as Rosa enferma stems from a personal history.11 Consequently, I continue to think about intimacy—to reimagine both the ties that bind and the ties that used to bind us to others—and about how to live, like the petals of Obregón’s roses, together apart.

—April 1, 2020

Kaira M. Cabañas is professor of global modern and contemporary art history at the University of Florida, Gainesville. She is the author of The Myth of Nouveau Réalisme: Art and the Performative in Postwar France (Yale University Press, 2013), Off-Screen Cinema: Isidore Isou and the Lettrist Avant-Garde (University of Chicago Press, 2015), and Learning from Madness: Brazilian Modernism and Global Contemporary Art (University of Chicago Press, 2018). Her next book, Immanent Vitalities: Meaning and Materiality in Modern and Contemporary Art, is forthcoming from University of California Press. She regularly contributes to Artforum.

- Fuenmayor and I cocurated the exhibition, which took place at University Gallery, University of Florida (UF), Gainesville, November 12, 2019–February 14, 2020, and included a satellite presentation of Obregón’s works from the collection at UF’s Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art. The exhibition’s installment at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum of Florida International University in Miami has been postponed until January 2021. Full disclosure: Fuenmayor is also my life partner. ↩

- Kaira M. Cabañas, “30th São Paulo Biennial,” Artforum, December 2012, 266. Luis Peréz-Oramas was the curator of the 30th São Paulo Biennial and also gave a Harn Eminent Scholar Chair in Art History (HESCAH) lecture in connection with the Obregón exhibition at the University Gallery/University of Florida Harn Museum: Luis Peréz-Oramas, “Achroma vanitas, Animal Image: Roberto Obregón and the Return of Nature in Venezuelan Art,” Harn Museum of Art, University of Florida, Gainesville, November 14, 2019. ↩

- In 1990 Obregón proposed to curators Jesús Fuenmayor and Miguel Miguel an installation that would contribute to destigmatizing AIDS in Venezuela. See Ariel Jiménez, Roberto Obregón en tres tiempos (Caracas: Exlibris and Colección Carolina y Fernando Eseverri, 2013), 188n73. ↩

- See the written inscriptions on Roberto Obregón, Rosa enferma / Disección real, 1981–82, dried petals adhered to paper and graphite on paper, 13 3/8 x 9 1/8 in. (33.3 x 22.9 cm), Colección Carolina y Fernando Eseverri, Caracas. Here Obregón notes how, in April 1982, when curator Susana Benko visited his studio, they discovered that the petals, which had been stored in an envelope, had been transformed by unidentified insects. ↩

- The original Spanish reads, “Blake no se refiere a la rosa enferma, sino a la enfermedad del amor.” Ariel Jiménez, interview with Roberto Obregón, November 2, 2002, reproduced in Jiménez, Roberto Obregón, 119. ↩

- Of the original document/work (Roberto Obregón, Rosa enferma / Disección real, 1981–82), Obregón writes that Salmerón gave him the rose in August 1981. I have opted for the precise date recorded in the chronology reproduced in Jiménez, Roberto Obregón, 188n73. There Obregón notes that Salmerón gave him the rose on March 26, 1981, and that the dissection was performed the following day. ↩

- The original Spanish reads, “Ese día la rosa que me había dado tomó para mí otra connotación, se convirtió en una verdadera alegoría.” Jiménez, Roberto Obregón, 180. ↩

- My discussion of a common corporeality is inspired by Judith Butler’s work. See her discussion in Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2004), 42–43. ↩

- To thus insist on a common corporeality is not to ignore how the pandemic also leads to new forms of control over populations and bodies. The dynamic between, on the one hand, experiencing an intensification of desire for love and care and, on the other hand, the pandemic’s implications in relation to power is captured by two of philosopher and activist Paul B. Preciado’s recent texts. The first deals in part with love and the second with biopower. See Paul B. Preciado, “The Losers Conspiracy,” Artforum, March 26, 2020; and Paul B. Preciado, “Aprendiendo del virus,” El País, March 28, 2020. ↩

- Since I completed this text on April 1 and submitted it for review to Art Journal Open on April 6, multiple news reports have identified the virus’s disproportionate impact on black communities in the United States. ↩

- See Preciado, “The Losers Conspiracy.” ↩