On June 11, 2008, accompanied by a number of Indigenous representatives and the legislative leaders of Canada’s major political parties, Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper delivered an official apology to former students and their descendants for the nation’s role in the establishment and administration of the Indian Residential School System (IRS).1 Referring to over 120 years of institutionalized racism, systemic abuse, and the attempted assimilation of tens of thousands of Indigenous children as a “sad chapter” in Canada’s history, Harper declared: “The government now recognizes that the consequences of the Indian Residential Schools policy were profoundly negative and that this policy has had a lasting and damaging impact on Aboriginal culture, heritage and language. . . . There is no place in Canada for the attitudes that inspired the Indian Residential Schools system to ever prevail again.”2

The temporal rhetoric employed for the apology has been much discussed: a strict division, it has been pointed out, was drawn between the residential-school era, when racist colonial attitudes prevailed, and a more informed and open-minded present, from which contemporary Canadians can look back and cast judgment.3 Pauline Wakeham and Naomi Angel, for example, argue that the tone of the apology implies a “retrospective model of witnessing” that confines wrongdoing to the past and shifts attention away from the present state of settler colonialism in Canada.4 This temporal distancing was reinforced “via the rhetorical deployment of anaphora, or the repetition of the phrase ‘we now recognize’ for strategic emphasis.”5 The phrase appears six times in a seven-minute speech of less than one thousand words. The implication is not only that the current administration and citizenry are absolved of any accountability for the atrocities under discussion but also that previous generations are exonerated, because “the wrongs they committed are only ‘recognizable’ as such ‘now,’ with the benefit of social enlightenment in the intervening years.”6 Thus, in both the past and the present, Canada’s culpability is implicitly mitigated. Indeed, anthropologist Eva Mackey has described the event as “a choreographed ritual of regret” wherein “over 200 years of colonial violence, momentarily brought to the foreground through the apology process, become contained in the past so that the nation may move forward into a unified future.”7 Aiming one’s sights on either the future or the past functions to sidestep any concern about the continuation of settler colonial structures in the present, and neither settler society nor the state is actively implicated or held accountable for upholding and benefiting from previously established colonial policies.

The temporal divide conjured in the government’s apology is firmly entrenched in Canadian national narratives and is consistently reinforced in the strategic deployment of the photographic record, especially the use of particular images to illustrate the distance between past atrocities and current attempts at reconciliation. There is a vast archive of photographs documenting—and produced primarily as propaganda for—the IRS, and these have become increasingly familiar to the Canadian public since at least the 2015 release of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), with its extensive use of archival images. Fabricated before-and-after photographs of children pre- and postassimilation; group portraits of students, dressed identically, divided by gender, and lined up in front of imposing brick buildings; and highly idealized images of children praying, learning, or exercising—the archive is extensive but provides little evidence of atrocities committed in the schools.

Here I argue that these images risk contributing to the banalization and historicization of colonial and racist structures, and I question the educational efficacy of their usual contextualization. Rather than engaging with the historical photographs as they typically appear, I focus my analysis on the work of N’laka’pamux/Secwepemc artist Chris Bose, who appropriates and reanimates archival images in order to account for their continued relevance and to refuse the relegation of colonial violence to the past. By exposing the omissions and biases built into the photographic record, this type of artistic action insists on a reexamination of the history and current state of colonialism in Canada in the interest of engendering greater settler accountability, or what Stó:lõ scholar Dylan Robinson has termed “intergenerational responsibility.” Robinson proposes the concept as a companion to the common invocation of sustained and inherited victimhood implied in labels such as “intergenerational survivor” or “intergenerational trauma.”8 Turning attention from victim to witness or perpetrator, Robinson proposes moving some of the burden of carrying history forward from the bearers and survivors of oppression to the descendants and inheritors of settler colonial privilege, renaming the latter “intergenerational perpetrators.”9

Of course, this requires a recasting of perpetration from active aggression to include inaction or indifference, and Robinson admits the designation may not be easy for much of settler society to accept, but he also argues that “changing the language we use in the work of redress asks individuals to recognize and change their perpetration of irresponsibility constituted by ignorance.”10 This is particularly important in the current political moment, wherein Canadian and global citizens are being forced to confront issues of systemic racism and inequity that remain rooted in colonialism. As the world has watched millions of Americans protest racial injustice in the United States following the high-profile police killings of unarmed Black men and women, including George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, Canadians have also been reckoning with ongoing issues of systemic racism and violence in policing, health care, and child welfare systems.11

Maintaining Ignorance

The government’s 2008 apology was broadcast live on national television, and both the written statement and video footage of the event were made available online. The artist and writer Chris Bose—himself the son of residential school survivors—has described being “both amazed and enraged” by Harper’s speech.12 In an artist statement for the 2013 exhibition Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery on the University of British Columbia campus in Vancouver, Bose writes of the apology: “I never thought it would happen in my lifetime, or even ever, but how empty it seemed and how quickly it came and went on the Canadian consciousness was unsettling.”13 Driven by these mixed emotions, Bose began the production of a large body of work responding to the legacy of the IRS, the potential impact and the inadequacy of the government’s apology, and the perpetuation of ignorance among the broader Canadian public. In December 2008 Bose launched the Urban Coyote TeeVee blog as an online platform for the development and sharing of a new piece of original digital art every day for a year.14 Having amassed thousands of archival photographs associated with Canadian settler colonialism, the history of the IRS, and the representation of Indigenous peoples, he incorporated them in a number of digital collages, photomontages, and films. In some cases, these images and assemblages include text from Harper’s statement of apology, juxtaposing the prime minister’s words with those of historical figures like John A. Macdonald or Duncan Campbell Scott, which appear alongside or over sepia-toned images of residential school students or faded photographs of Indigenous dancers.

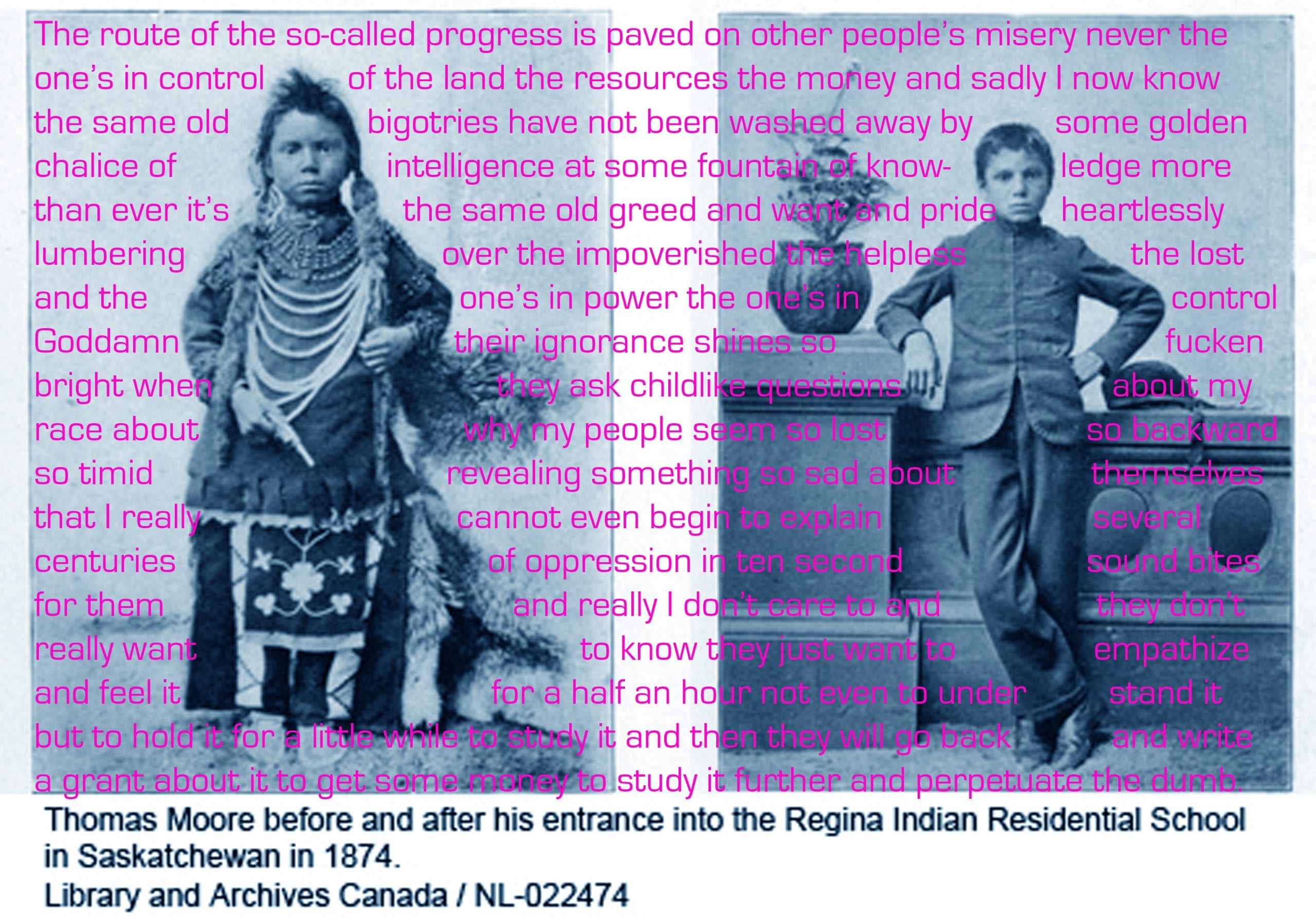

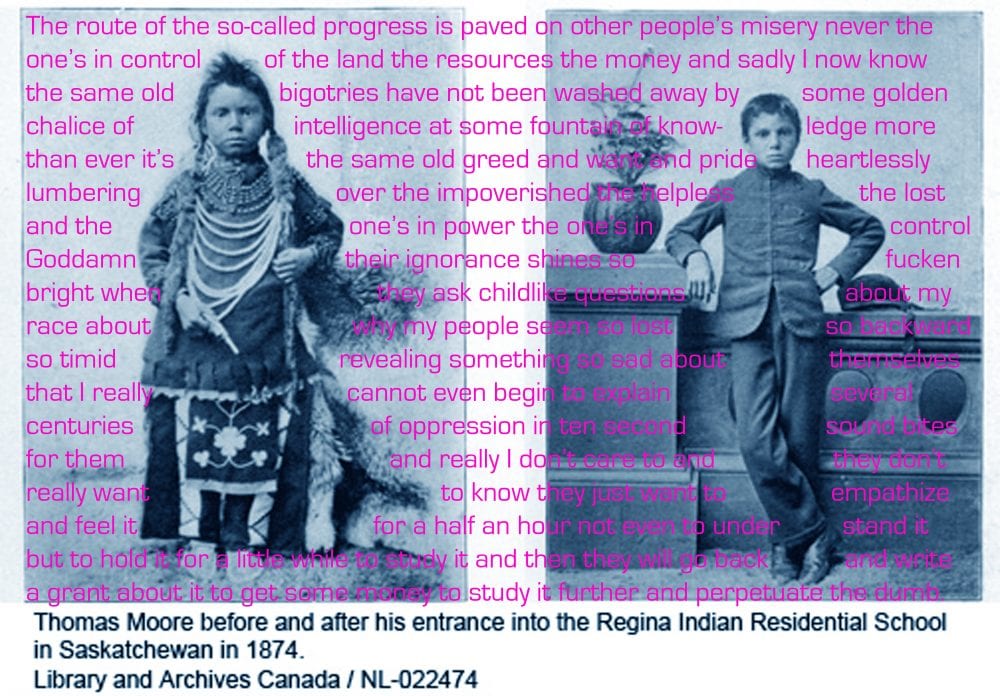

(artwork © Chris Bose, provided by the artist)

One of these images, posted on May 18, 2009, remobilized an infamous pair of photographs depicting Cree child Thomas Moore before and after his enrollment in the Regina Indian Residential School.15 Titled here you go canada, ask me another stupid question, the diptych is overlaid, in this case, with Bose’s own stream-of-consciousness writing. Unpunctuated and unedited, the artist’s words are printed in horizontal lines, from top to bottom, broken only where they would otherwise cover the figure of Moore. The text reads:

The route of the so-called progress is paved on other people’s misery never the one’s in control of the land the resources the money and sadly I now know the same old bigotries have not been washed away by some golden chalice of intelligence at some fountain of knowledge more than ever it’s the same old greed and want and pride heartlessly lumbering over the impoverished the helpless the lost and the one’s in power, the one’s in control Goddamn their ignorance shines so fucken bright when they ask childlike questions about my race about why my people seem so lost so backward so timid revealing something so sad about themselves that I really cannot even begin to explain several centuries of oppression in ten second sound bites for them and really I don’t care to and they don’t really want to know they just want to empathize and feel it for a half an hour not even to understand it but to hold it for a little while to study it and then they will go back and write a grant about it to get some money to study it further and perpetuate the dumb.16

Layering the text over the paired portraits, Bose draws direct connections between the forced reeducation of children like Moore, current societal dysfunction, and the ongoing ignorance of the Canadian public in regard to both this history, with its enduring impact on multiple generations of Indigenous people, and the broader system of settler colonial oppression. The juxtaposition of text and image in this work both resists the consignment of settler colonialism and white supremacy to the past, as was implied in the government’s statement of apology, and demands more of the spectator than retrospective witnessing. Indeed, playing on Harper’s refrain of “we now know,” the second line of Bose’s text reads, “Sadly I now know the same old bigotries have not been washed away by some golden chalice of intelligence at some fountain of knowledge.” With this turn of phrase, Bose refutes the suggestion that past wrongs can only be recognized as such now, with the historical hindsight of an enlightened populace, unburdened of responsibility for these earlier atrocities and unaccountable for their perpetuation in the present. Rather, the work implores spectators to close the presumed temporal divide and read continuity into history.

Referring to “several centuries of oppression” instead of residential schools specifically, Bose further insinuates that the violence of the IRS cannot be isolated from the larger and ongoing process of settler colonialism in Canada. Indeed, in addition to reinforcing assumptions of temporal distance, the strategic vocabulary employed in the statement of apology betrays an attempt to justify the Canadian government’s role in running the schools, “partly in order to meet its obligation to educate Aboriginal children.”17 As Wakeham and Angel argue, the effect is an implicit disarticulation of the IRS from settler colonialism’s “multi-pronged assault on Indigenous lifeways,” which risks minimizing or obscuring the scope of oppression.18 As Mackey states, “By limiting the apology and the redress to residential schools, the official apology carved out a very small part of a much broader process of cultural genocide,” including the theft of Indigenous land, the disregard for treaty obligations, the denial of Indigenous sovereign rights, and an overarching attempt to eliminate Indigenous presence.19 Additionally, the apology failed to acknowledge the degree to which the removal of Indigenous children from their families and communities, and their placement in often abusive, unsafe, and culturally disconnected environments, continues in the current child welfare system, with more Indigenous children currently in foster care than were ever incarcerated in residential schools.20 Despite this readily available information, Robinson argues, “a large portion of the settler Canadian public remains aggressively indifferent toward acknowledging the history of colonization upon which their contemporary privilege rests.”21

The miseducation and ignorance of settler society to which both Robinson and Bose refer is arguably also an effect of the gaps and omissions in the photographic record and the perpetual circulation of images that, without due attention, risk obscuring atrocity and sanitizing history. Indeed, despite the IRS’s continued operation well into the 1990s, the perpetual selection and circulation of older black-and-white or sepia-toned images by the mainstream media, educational platforms, and even the TRC has arguably contributed to the perception that the era of aggressive assimilation is more distant than it actually is. The reproduction of such images, without reference to dates or other specificities, as Wakeham and Angel describe, “generates a semiotics of pastness” that shifts attention away from the present.22

The Art of the Apology

Along with his series of composite digital images, Bose produced an eleven-minute video work, titled The Apology, as part of a 2011–12 residency at Vancouver’s UNIT/PITT gallery. The short film consists of archival footage of Vancouver in 1941 mixed with panoramic shots of the contemporary city and rare video footage of Indigenous children in an undisclosed residential school. The audio, which begins abruptly at 2:05 minutes, is taken directly from Harper’s apology, edited and remixed by the artist so that significant words or phrases are repeated or enhanced by an echo effect and moments of silence are introduced throughout. The prime minister’s repetition of phrases, described by Wakeham and Angel as a strategic device to abdicate responsibility and create a greater degree of temporal distance, is overridden by Bose’s editing; Harper’s refrains are replaced with other, equally significant repetitions. The most virulent or violent terms—glossed over or merely muttered in the original statement—are repeated with increasing volume, so that they seem to ring in listeners’ ears. Phrases like “assimilate them into dominant culture,” “kill the Indian,” “some of these children died” and “extraordinary courage” echo over the footage of students, surrounded at all times by church and school administrators. Dressed in uniforms, the children line up to have the identification numbers written on their arms checked and recorded; girls in white communion dresses walk behind nuns, stepping solemnly in time with one another. Some scenes depict clergy and staff raising a British flag on the school grounds, and others show them seated in front of a makeshift stage on which a group of (presumed) students wearing headdresses and tasseled clothes drum and dance for them.

The juxtaposition between the audio and the visuals is unsettling, and the footage itself is haunting. The film’s ghostliness is enhanced by the artist’s editing techniques: the children’s faces become blurred and their expressions are washed away by overexposure, their bodies reduced to silhouettes, fading into a range of shades and colors, vanishing and then appearing again, fully present. Three minutes before the end of both the film and the statement of apology, the footage begins again and then is repeated a number of times—at increasing speed, fast-forwarded and in reverse, the children running backward and forward, caught in the inescapable cycle of the video loop.

Beyond the deliberate actions of the artist to highlight certain elements of the government’s apology and the historical atrocities to which it refers, and beyond the visual manipulation of the archival imagery, the effectiveness of Bose’s film comes from the rarity of seeing moving images—even color footage—of residential school students. Much of the IRS’s visual documentation shared with the public consists of black-and-white stock photographs that infer significant temporal distance from the present, despite the system’s continued operation well into the last decade of the twentieth century. What is more, the formulaic composition of residential school photographs, produced primarily as propaganda, by and large do not conform to conventional images of atrocity or human rights violations and risk contributing to historical denial of the violence and genocidal underpinnings of the IRS. The Apology breaks with this form of misrepresentation by both departing from the usual reliance on black-and-white still images and pairing the moving footage with the government’s 2008 statement. The combination of audio and visual footage and the accentuating of the most damning or atrocious phrases—“kill the Indian . . . kill the Indian”—as well as significant statements of strength and resilience—the “extraordinary courage” of survivors—engenders a sense of continuity and contemporaneity in regard to the legacy of residential schools and settler colonialism more broadly.

The Apology confronts and challenges what TRC commissioner Marie Wilson has termed the “comfortable blindness” of the Canadian public concerning their colonial history,23 as was particularly evident in its initial exhibition, projected onto busy public streets in a part of Vancouver where a majority Indigenous, low-income, and homeless population neighbors the city’s bustling business district. The various juxtapositions within Bose’s film, including the camera’s scanning of Vancouver’s waterfront, taking in the cityscape and oil tankers in the harbor, link the IRS to the larger settler-colonial system of dispossession, resource extraction, and occupation of unceded territories. Mackey has pointed out that “the words ‘land,’ ‘territory,’ or ‘treaty’ simply do not appear in the text of the Harper apology,” despite the intertwining of assimilationist reeducation policies, the strategic statistical reduction of First Nations populations, and the appropriation of Indigenous territories.24 Obscuring these links allows settler Canadians to avoid uncomfortable realizations that they are “all contemporary beneficiaries of this process.”25 What is more, when this history is framed as fundamentally past—in the statement of apology or in the continued circulation of uncontextualized historical images—the risk is greater that recognition of colonial oppression remains retrospective.

Turning to the Present

Five years after the completion of the TRC’s mandate and the release of its report and recommendations, Canadians find themselves in a political moment that has forced a reckoning with issues of systemic racism and state violence. Following a series of highly publicized police killings of Black and Indigenous people in the United States and Canada and the emergence of what might be the largest social justice movement in US history, an Ipsos poll from July 2020 found that “more Canadians see racism as a serious problem today than one year ago.”26 But, while awareness of structural racism has certainly increased, and the work of the TRC, among other organizations, has done much to educate the public on the history of colonialism and cultural genocide in Canada, the fundamental connection between the past and the present too often remains unacknowledged, and vast inequalities between Indigenous and settler Canadians remain. In terms of child and family services, Indigenous children are still overrepresented in the welfare system, making up over 50 percent of minors in foster care while accounting for only 7 percent of the country’s youth population.27 Children are still being separated from their families and communities, are still underserved, and are dying in care at alarming rates.28 And while the federal government, in response to some of the TRC’s recommendations, has recently tabled a bill intended to put control over youth services back in the hands of Indigenous nations and organizations, they are at the same time appealing a ruling by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal demanding that Ottawa pay billions of dollars in compensation to families unnecessarily separated since 2006 by a discriminatory and chronically underfunded child welfare system.29 These inconsistencies and delay tactics in the face of present-day inequities risk discrediting any reconciliation efforts or apologies the government makes.

Canada has become adept at apologizing for past wrongs, and Canadians are becoming increasingly cognizant of contemporary inequalities, but the words and images chosen to address the country’s colonial history often fail to firmly link the past to the present. Works like here you go canada, ask me another stupid question and The Apology provide evocative and necessary corrections to the dominant narrative surrounding Canadian colonialism. In fact, Bose’s work with both still and moving images functions similarly to Robinson’s recasting of settlers as intergenerational perpetrators: both confront Canadians with their own complicity or indifference and challenge them to make a conscious shift from apathy to accountability.

Reilley Bishop-Stall received her PhD from McGill University, Montreal, in 2019 and is currently a postdoctoral fellow with the Inuit Futures in Arts Leadership: The Pilimmaksarniq / Pijariuqsarniq Project at Concordia University, Montreal. Bishop-Stall’s work has been published in peer-reviewed journals including Photography & Culture and The Journal of Art Theory and Practice.

- Following the prime minister’s statement, the leaders of each opposition party delivered their own remarks and, in a last-minute decision, for the first time in history Indigenous representatives were permitted to address Parliament and respond to the apology. See Eva Mackey, “The Apologizers’ Apology,” in Recognizing Canada: Critical Perspectives on the Culture of Redress, ed. Jennifer Henderson and Pauline Wakeham (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013), 59. See also Government of Canada, “House of Commons Debate, 39th Parliament, 2nd Session,” Edited Hansard 142, no. 110 (June 11, 2008). ↩

- Click here to read the Statement of Apology in full. ↩

- See, for example, Mackey, “Apologizers’ Apology”; Pauline Wakeham and Naomi Angel, “Witnessing in Camera: Photographic Reflections on Truth and Reconciliation,” in Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action in and beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, ed. Dylan Robinson and Keavy Martin (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016), 94–137; Matthew Dorrell, “From Reconciliation to Reconciling: Reading What ‘We Now Recognize,’ in the Government of Canada’s 2008 Residential Schools Apology,” English Studies in Canada 35, no. 1 (2009): 27–45; and Pauline Wakeman, “The Cunning of Reconciliation: Reinventing White Civility in the ‘Age of Apology,’” in Shifting the Ground of Canadian Literary Studies, ed. Smaro Kamboureli and Robert Zacharias (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2012), 209–33. ↩

- Wakeham and Angel, “Witnessing in Camera,” 99. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 100. Of course, evidence of the ill-health and poor treatment of residential school students has been readily available since the earliest days of the system’s administration. ↩

- Mackey, “Apologizers’ Apology,” 60. ↩

- Dylan Robinson, “Intergenerational Sense, Intergenerational Responsibility,” in Robinson and Martin, Arts of Engagement, 48. In fact, Robinson points to the fervent adoption of these terms by the TRC to describe descendants of residential school students. ↩

- Ibid., 65–66. ↩

- Ibid., 67. ↩

- Over the spring and summer months of 2020, while much of the world was in lockdown due to the global coronavirus pandemic, protests against racism and police brutality that began in the United States also occurred across Canada. In the weeks surrounding the May 25 death of George Floyd in Minnesota, video footage surfaced of the violent arrest of Chipewyan First Nations Chief Allan Adam by Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) officers; Winnipeg police killed three Indigenous people, including a sixteen-year-old girl, over a period of ten days; at least five people of color were killed by RCMP officers who had been called to perform “wellness checks”; and, more recently, an Atikamekw woman livestreamed the last moments of her life in a Quebec emergency room, revealing hospital staff assaulting her with racist and sexist slurs as she died. These and other events have spearheaded debates about systemic racism and colonial violence in Canada and have inspired extensive protest and collective action, including the symbolic act of toppling a downtown Montreal statue commemorating Canada’s first prime minister and the architect of the Indian Residential School system, John A. Macdonald. See “Activists Topple Statue of Sir John A. Macdonald in Downtown Montreal,” CBC News, August 29, 2020. ↩

- Chris Bose, “Artist Statement,” Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools (Vancouver: UBC Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, 2013): 38. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Following the initial year-long project, Bose has kept the website active, posting writing and artworks at a continuous, although more occasional, rate. See Chris Bose, Urban Coyote TeeVee (blog). ↩

- The pair of photographs follows a formula that was common in both Canadian and American propaganda promoting such schools. This particular pair appeared in both the 1896 and 1904 Department of Indian Affairs annual reports and has been reprinted in countless books and contemporary documents detailing the history of the IRS. ↩

- Chris Bose, “here you go canada, ask me another stupid question . . , ” Urban Coyote TeeVee (blog), May 18, 2009. ↩

- Government of Canada, “House of Commons Debate.” ↩

- Wakeham and Angel, “Witnessing in Camera,” 95. ↩

- Mackey, “Apologizers’ Apology,” 61. ↩

- In the executive summary of its final report, the TRC describes the way in which the dissolution of the IRS coincided with the “Sixties Scoop,” during which thousands of Indigenous children were apprehended by child welfare services and placed in non-Indigenous homes across the country, with no effort toward ensuring cultural preservation or transmission. It further reported that this process continues today: “Canada’s child-welfare system has simply continued the assimilation that the residential school system started.” Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Summary: Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 2015): 138. ↩

- Robinson, “Intergenerational Sense,” 63. ↩

- Wakeham and Angel, “Witnessing in Camera,” 98. ↩

- Ibid., 95. ↩

- Mackey, “Apologizers’ Apology,” 63. ↩

- Ibid., 61. ↩

- Katie Dangerfield, “More Canadians Say Racism Is a ‘Serious Problem’ Today than 1 Year Ago: Ipsos Poll,” Global News, July 24, 2020. ↩

- First Nations Child and Family Services, Indigenous Services Canada, Government of Canada, “Reducing the Number of Indigenous Children in Care,” February 20, 2020. ↩

- See Rhiannon Johnson, “Indigenous Children Are Dying in Canada’s Foster Care System,” Vice, May 4, 2017. ↩

- The tribunal ruled that Canada “willfully and recklessly” discriminated against Indigenous children on reserves by providing inadequate funding in comparison to that offered to off-reserve Canadian children. The government appealed the decision in October 2019 and the issue remains unresolved. See Teresa Wright, “Trudeau Government Appeals Ruling on Compensation to First Nations Children,” Canadian Press, October 4, 2019. In June 2019 the government introduced Bill C-92, Act Respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis Children, Youth and Families, to Affirm Indigenous People’s Jurisdiction over Child and Family Services and Establish National Standards and Principles for Care. ↩