1A Re-creation by Brenna McMann (@vintageren), Instagram, April 8, 2020 (published under fair use)

1B Bernhard Strigel, Portrait of Martha Thannstetter (née Werusin), ca. 1515 (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by Scala/Art Resource, NY)

Toilet paper and hand sanitizer may have been scarce in stores during the coronavirus lockdown, but they featured prominently on social media in the re-creations of fine art that went viral beginning in March 2020 (Figs. 1A, 1B). Home cleaning supplies provided a palette for stay-at-home #instaart photographs that soon numbered in the tens of thousands. This is how the art lover did self-isolation in the face of COVID-19 museum closures. As airlines suspended flights and institutions locked their doors, museumgoers responded to the distance placed between them and their cherished artworks by reenacting those very objects. In the midst of this public health crisis and accompanying confinement, immobility motivated mimicry.

The global phenomenon of tableau making that surfaced when access to art came to a startling halt is worthy of art historical analysis. Imitating works of art is not a new practice—these modern-day copyists are participating in acts of repetition that date back to antiquity. However, the form of that participation has changed in the LOL culture of online communication. Quarantine encouraged a museological practice in which physical immobility created a new cyber community focused on the copy. Through a historical analysis of the act of copying, I argue that these mise-en-scène remakes reimagined ideas of subjectivity and selfhood in the age of COVID. Here I study the most popular quarantine copies that circulated on social network sites at the outset of the pandemic, with a keen eye on Renaissance-inspired imagery.1 In early modernity, the copy found new cultural consequence with the rise of the status of the artist; the emergence of a burgeoning art market; claims on the authenticity of the artist’s hand by patrons, collectors, connoisseurs, and dealers; and the development of “the individual.”2 I argue that such historical traditions provide us insight into how the COVID re-creations reconceptualized the self in a moment of self-isolation.

Just as London’s Victoria and Albert Museum solicited Britons to send in handmade signs that had been placed in residential and commercial windows during the lockdown, Los Angeles’s Getty Museum and Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum challenged patrons to re-create their favorite work of art using whatever their house had. Initially inspired by the Dutch Instagram account Tussen Kunst en Quarantaine (@tussenkunstenquarantaine), these museums encouraged creators to connect anew with Leonardo da Vinci, Artemisia Gentileschi, Johannes Vermeer, Tōshūsai Sharaku, Frida Kahlo, and Pablo Picasso. On March 25, 2020, the Getty used Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram to call art enthusiasts to action: “We challenge you to recreate a work of art with objects (and people) in your home. 1. Choose your favorite artwork; 2. Find three things lying around your house; 3. Recreate the artwork with those items. And share with us.”3 The Getty’s digital content editors, Sarah Waldorf and Annelisa Stephan, provided pointers on best practices, including the use of pets as props, sassy facial expressions, curated lighting, and abstract thinking.4 In an interview with PBS NewsHour, Stephan expressed surprise at the vast number of submissions: the Getty expected around thirty entries, but by mid-April, only a month into the global lockdown, that number had exceeded thirty thousand.5

Museums have capitalized on the trending power of social media. Beginning in 2013, museums of all kinds dedicated the third Wednesday in January to Museum Selfie Day, a day in which museums lift their restrictions on photography and allow visitors to snap a selfie beside their favorite object(s).6 Many large museums such as the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum of Art already permit still photography in their permanent collections for noncommercial use. The selfies that American supercouple Beyoncé and Jay-Z shot in 2014 when they rented out an emptied Louvre embraced this new trend and instantly ignited a myriad of memes. Celebrities were not alone in their desire to strike a pose with legendary masterpieces, and through partial release of photographic restrictions museums democratized their galleries.

2A Re-creation by Manny and Leo Avetisyan (@manaty_life), Instagram, April 17, 2020 (photograph by Natalia Avetisyan)

2B Peter Paul Rubens, Saturn Devouring His Son, 1636 (artwork in the public domain; photograph by Erich Lessing, provided by Art Resource, NY)

Yet the quarantine copies that hit social media during the pandemic reference a different form of cyber participation than that organized by the #MuseumSelfie movement. While museum selfies depict the self alongside the work of art, the quarantine images portray the self as the work of art. These dress-up tableaux of renowned paintings and sculptures are not duplicates of their illustrious antecedents. They do not seek to replicate the original with fidelity. Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, posted by u/Krlmhl, or Peter Paul Rubens’s Saturn Devouring a Son, posted by @manaty_life, reference the ur-image through playful props and choreographed poses (Figs. 2A, 2B). They also denote “home” through their blanket backdrops and towel loincloths. Many of the quarantine copies feature stuffed animals, vacuum cleaners, macaroni noodles, and plastic pails. Isolation within the house inspired domestic improvisations.

3A Re-creation by Jenny Boot (@jennyboot2), Instagram, March 6, 2018 (went viral in 2020)

3B Johannes Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring, ca. 1665. Mauritshuis, The Hague (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by Bridgeman Images)

The Getty’s recently released picture book Off the Walls offers a collage of such museum challenge images.7 The mystique of Vermeer’s seventeenth-century Girl with a Pearl Earring captured the imagination of many twenty-first-century quarantiners. These submissions feature bearded men, pouty dogs, assembled foodstuffs, and even a desk lamp donning the sitter’s memorable yellow and blue turban. The homogeneity of Vermeer’s oeuvre is placed in contradistinction to the diversity represented in re-creations of the pearled beauty. These homemade simulants include the presence of racial, gender, national, and intergenerational difference. Photographer Jenny Boot posted on Instagram a remake that includes a model looking over her left shoulder in three-quarters view (Figs. 3A, 3B). Boot replaces the chromatic variations of Vermeer’s work with a monochromy that harmonizes with the sitter’s dark skin and celebrates her Blackness. Direct lighting effects illuminate her flawless complexion and emphasize the reflective surfaces of her white pearl drop earring, chiaroscuro eyes, and raspberry glossed lips. Art historians suggest that the word “Baroque” derives from the Portuguese term for uncultured pearl (barroco); it is fitting, then, that Boot—channeling the Dutch Baroque master Vermeer—alters a pearl-focused work to create a modern-day revision with renewed cultural relevance.

Dressing up as Vermeer’s imaginary figure is nothing new; the painting has inspired many Halloween costumes. However, the social resonance of artful dress-up unequivocally changed during the COVID lockdown. Craving the museum in a moment of global immobility, homebound copyists turned to the turbaned sitter as a form of self-distraction or self-assertion to combat the isolation of quarantine.

As exemplified in this Vermeer from the Mauritshuis collection, the conditions for participation in the Getty Museum Challenge did not require mining examples exclusively from the Getty. The Getty website recommends that potential re-creators study the online collections of many museums: “LACMA, The Met, Cleveland, Indianapolis, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Walters, or the National Gallery.”8 They then advise those participants to “share your creation with the world.”9 While Museum Selfie Day is a global event that focuses patrons’ attention on local museums, the pandemic museum challenge asks local individuals to think globally. These reenactors become living and breathing avatars, real people transformed via digital photography following their virtual visit to the world’s museum collections.

Copying Botticelli’s Birth of Venus with a potted fern landscape or Raphael’s Sistine Madonna with DIY angel wings made from cut paper plates is not just a lesson in art appreciation. It is a performative pedagogy that teaches us the role the museum plays in our collective humanity. As Ellery E. Foutch notes, “The act of researching and performing tableaux vivants compels students to look closely, to research works of art, to think critically, to interpret and create, and to engage in metacognitive and embodied experiences.”10 The act of emulation personified in these tableaux physicalizes art history. For the COVID copyists, parroting practices of simulation made the static scenes of the museum come alive in quarantine. An economy of emulation emerged via a social media event that combined the public and private self in a form of sequestered spectacle, reminding quarantiners of the “transformative spiritual, ethical, and emotional power” of the art museum.11

4A Re-creation by Squidrobots (u/squidrobots), Reddit, April 18, 2020 (photograph provided by Angelica Ballard)

4B Andrea Mantegna, Madonna and Child, ca. 1480 (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by Scala/Art Resource, NY)

5A Re-creation by @covidclassics, Instagram, April 11, 2020

5B Artemisia Gentileschi, Susanna and the Elders, 1610 (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by incamerastock/Alamy Stock Photo)

As museum challenge participants enacted art objects in static postures, their work blurred traditional boundaries of genre. Contemporary history paintings and genre scenes transformed into present-day portraits, as the visages of the re-creators (and their pandemic pods) personalized the copy. Authorship shifted from the canonical artist to the COVID copycat. These quarantine imitators never intended to forge the venerable original. Instead, the true protagonists were the re-creators themselves, who wanderlusted in place. When restaged within the domestic interior, sacred art secularized in the typical quarantined home. On Reddit, u/squidrobots became Andrea Mantegna’s Madonna and Child with a fitted blue bedsheet replacing the Virgin’s lapis lazuli headcover (Figs. 4A, 4B). On Instagram, the @covidclassics roommates, quarantined friends who drew nearly ninety thousand followers from their forty-five posts, became Artemisia Gentileschi’s Susanna and the Elders (Figs. 5A, 5B). It was not piety that inspired the scantily clad Sam Haller of East Rock, Connecticut, to play the role of Susanna. According to an interview he gave to the New Haven Independent, public praise and exhibitionism fueled his participation in the re-creations.12

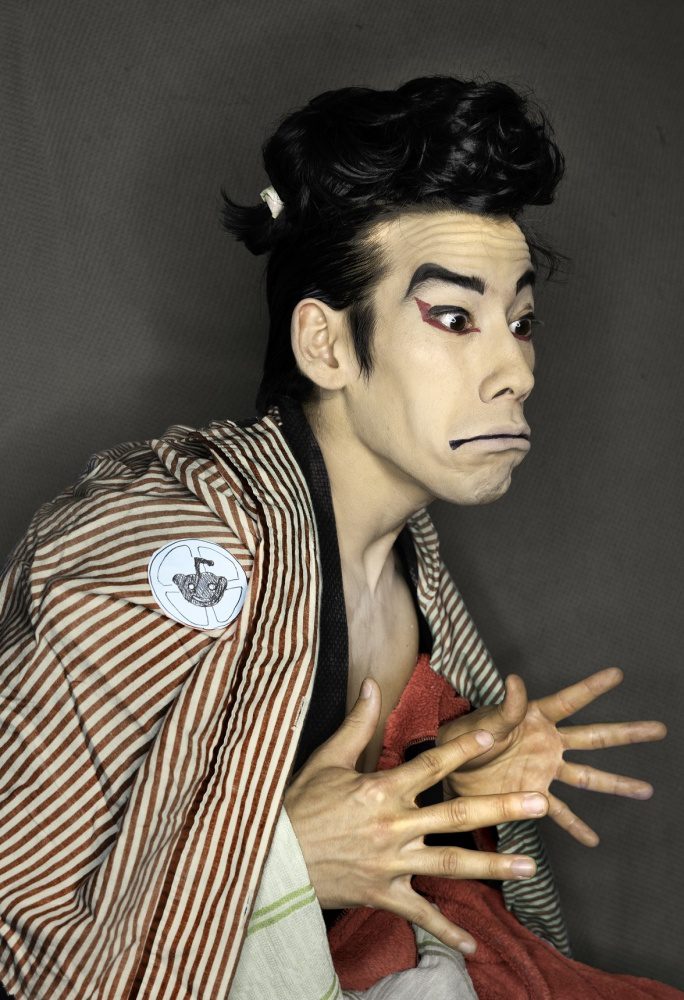

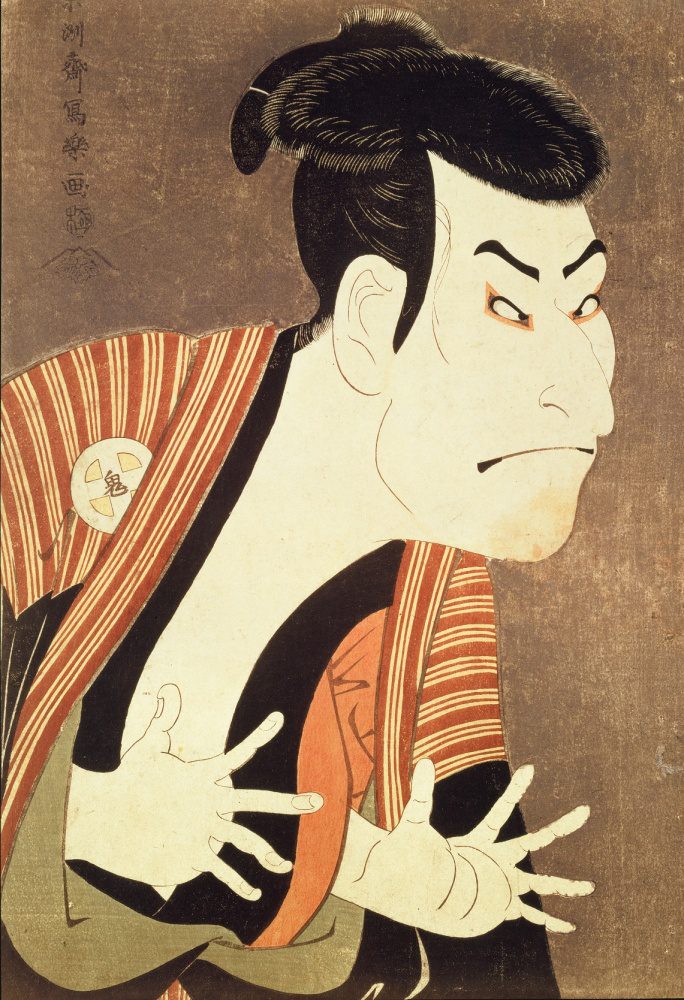

6A Re-creation by Kento Mizuno (u/kento-box) and Katie Mizuno, Reddit, May 16, 2020 (photograph by Kento Mizuno, @kentomizunodesign, and Katie Mizuno, @katiemizuno)

6B Tōshūsai Sharaku, Kabuki Actor Ōtani Oniji III as Yakko Edobei in the Play “The Colored Reins of a Loving Wife (Koi nyōbō somewake tazuna),” 1794. British Library, London (artwork in the public domain; photograph © British Library Board. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images)

Portraiture also turns to self-portraiture. For example, the Reddit user u/kento-box documented his process of self-representing Tōshūsai Sharaku’s woodblock print of actor Ōtani Oniji III in the role of the servant Edobei (Figs. 6A, 6B).13 This particular autodepiction, executed in collaboration with @katiemizuno, embodies a layering of identities: from titular servant to kabuki actor to self-isolating imitator. U/kento-box’s selfie appearance is inseparable from Sharaku’s historical portrait. To corroborate that visual analogy, he presents his self-image on Reddit with the caption: “My fiancée says I’m handsome . . . like a Japanese woodblock print.”14 Here u/kento-box personalizes Japanese woodblock art through his homespun ukiyo-e performance. His selfie is relational; it references a past artistic tradition with the singularized face of the present.

Technology also plays a role in genre blurring. Media studies scholars underscore the difficulties in distinguishing between the self-portrait and the selfie.15 The advertisement campaign for the Samsung NX Mini entitled “Masterpiece” highlights such debates. In one ad, Albrecht Dürer, seen from behind, takes a picture of himself with the smart camera (Fig. 7).16 In its flip-up display, we see Dürer’s 1498 self-portrait (Museo del Prado). The tagline at the bottom of the page reads: “For self-portraits. Not selfies.” Differentiating categories of self-photography may prove challenging, but the selfie is particular in that it relies on smart technology and social network sites. With the selfie, the face becomes an interface intended for public consumption on social media.17

No matter how proximate or elastic the genre, the museum challenge images have much in common. They all present their authors as art lovers with remarkable visual acuity. They all function as metonyms for self-quarantine. And they all were intended for social media. The individuals depicted situate themselves in the world.18 Images staged in the United States, the Netherlands, Spain, Russia, Norway, Iran, and beyond participate in an open and responsive technological network that creates affiliations between individuals living in different countries and on different continents.19 These tableaux were “conceived for being feedbacked and looped further on the internet.”20 They activate a networked community in which socialization during isolation is shared and participatory within the public domain. These images represent isolation, but they are not isolationist. On the contrary, the museum challenge images make private domesticity public on the internet’s world stage. Tableau creation documents the isolation of the COVID quarantine as a phenomenon of mass visual culture.

Counterfeiting, forging, replicating, imitating, re-creating, remaking, and reincarnating are not analogous concepts in the history of art, nor are they interchangeable. These terms differ in relation to issues of aesthetic taste, social identity, and cultural value. The duplication of works of art in their varying conditions and contexts renders the word “authenticity” imprecise and inconsequential. Nevertheless, what joins these disparate yet homologous concepts of reproduction is a desire to acknowledge the distance (geographical, temporal, cultural, moral) between the original and the copy. The discipline of art history recognizes that distance to contend with the resulting ripple effects.21

The history of art abounds in the art of reproduction. Copying works of art dates back to Roman antiquity. The Kopienkritik tradition, in which Roman replicas stand in for lost Greek originals, still informs studies of Roman sculpture.22 The art of ancient Rome offers strategies for exploring how copying motivates innovation, eclecticism, and emulation.23 In early modernity, the geographic reach of the copy expanded across oceans and continents with the advent of the print. “Old World” paintings found “New World” form vis-à-vis the circulation of printed facsimiles.24 Repetition may help us recognize originality, or, as Maria H. Loh argues, repetition is itself a form of originality.25 Copies overcame physical distances to make immediate the original prototype.

Imitation may indeed be the sincerest form of flattery—and it has a long history. During the Renaissance, copying was a pedagogy that served to train great masters and apprentices alike. Michelangelo copied Masaccio’s Tribute Money in a drawing now housed in the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung in Munich.26 The Bolognese engraver Marcantonio Raimondi reproduced in print Raphael’s Parnassus fresco in the Vatican’s Stanze della Segnatura. Raphael so admired Marcantonio’s work that the two High Renaissance artists combined their manual and mechanical skills in graphic collaborations, ultimately culminating in the Massacre of the Innocents engravings.27 During a trip to Spain in August 1628, Rubens famously copied Titian’s Rape of Europa, one of Philip IV’s most treasured paintings. Titian himself copied the recumbent nude of Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus and then repeated that donna nuda format over and over again at the request of dukes, kings, and cardinals. Serial repetition did not injure the archetype. According to Loh, the artistic processes of repetition instead perpetuated the emulative desires of Titian’s esteemed (male) patrons.28

In the 1568 edition of Lives of the Artists, Giorgio Vasari describes how copies at times brought early charges of copyright infringement. The skilled storyteller details the ire Marcantonio incited in Dürer when counterfeiting his prints.29 Vasari’s accounts have some inconsistencies, but Marcantonio did in fact reproduce Dürer’s woodcuts from The Life of the Virgin series around 1506, right down to Dürer’s own “AD” monogram. Dürer, according to Vasari, brought suit against Marcantonio in Venice for pirating his work. The Venetian Signoria found Marcantonio’s plagiarized copies lawful but prohibited his use of Dürer’s monogram. Vasari was a teller of tall tales, so this anecdote about the lawsuit may be apocryphal.30 Yet an analogous case involving Dürer took place in Nuremberg against a foreign forger, who was compelled by the city council “to remove all the said monograms.”31 Selling prints with Dürer’s monogram was criminal; however, the courts found counterfeiting the composition, sans signature, an acceptable practice in the visual arts. Counterfeiting works of art was not a fraudulent act in early modernity. An imago contrafacta was a practice of reportage in which an artist faithfully copied an image of visual interest without (or with nominal) emendation.32 Contrafacta does not carry the negative connotations of its English cognate. In fact, early moderns used the term to describe the rendering of portraits or nature with an exacting eye.

8A Hazel Lavery as Flora in Botticelli’s Primavera, 1913 (photograph provided by Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo)

8B Sandro Botticelli, Primavera, ca. 1482, detail of Zephyr and Flora. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by ItalyPhoto, © Raffaello Bencini/Bridgeman Images)

By the late eighteenth century, copying took on a new form through tableaux vivants, or “living pictures,” that merged the visual and performing arts. A popular practice of Enlightenment-era entertainment, tableaux vivants consisted of people staged to imitate works of art or prominent historical or literary scenes. For instance, Hazel Lavery (the wife of Irish painter Sir John Lavery) attended the 1913 Picture Ball dressed as Flora in Botticelli’s Primavera with a gold metal wig and diaphanous dress strewn with flowers (Figs. 8A, 8B).33 Copying in this context dramatized visual art to elevate the social status of its aristocratic and bourgeois practitioners. Today the emulative powers of tableaux can be found in pop culture. In her 2013 music video for “Mine,” Beyoncé dons a Carrara-colored strapless dress and cradles a youth painted marble white as a modernization of Michelangelo’s Pietà (see timestamp 1:16). She again turned to early modern visual traditions in 2017 when she announced her pregnancy and then the birth of twins Sir and Rumi on social media. Posed before a floral mandorla, Beyoncé becomes both Virgin and Venus.

Art history recognizes distinctions in mimicry to address the distance, whether near or far, between the original and the copy. In the age of COVID, the travel bans and museum closures imposed during the 2020 lockdown underscored that distance, and the quarantine copies embodied its vastness through their sheltered settings. In a moment when in-person social relationships were limited to members of a single household, art enthusiasts turned to the museum challenge to collapse that distance. According to sociologist Gabriel Tarde, “Any social production . . . tries to multiply itself by thousands and millions of copies in every place where there exist human beings.”34 Repetition, he argues, fosters social relations between individuals. Even in isolation (or especially because of it), the act of imitation creates social connection that requires us to confront ourselves as social beings.35 We remake renowned works of art starring ourselves to understand ourselves. We create living pictures to show ourselves living. These works unmistakably index the self in self-isolation. Perhaps it is unsurprising that self-quarantine inspired self-analysis. The limitations of isolation require us to confront the self.

These domestic tableaux were not quite what Walter Benjamin had in mind when he wrote, “In principle a work of art has always been reproducible. Man-made artifacts could always be imitated by men.”36 In his 1936 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Benjamin explored how new media such as photography and film altered our understanding of aesthetic value. Benjamin’s humorous side may have delighted in the pet cats or stuffed tyrannosaurus replacing the ermine in quarantine versions of Leonardo’s portrait of Cecilia Gallerani.37 He may have equally enjoyed the acoustic guitar substitute for the lute played by Rosso Fiorentino’s musical angel, the avocado flanked by two spoons that re-creates Edvard Munch’s The Scream, and the miscellaneous charcuterie dancing around a trenchcoated gentleman in an adaptation of Francis Bacon’s Second Version of Painting 1946. Benjamin might have seen these images as laughter-inducing re-creations of celebrated masterworks; however, he did not affirm mechanical reproduction, arguing technical reproducibility depreciated the “aura” of the work of art to challenge its singularity. Embedded with specific temporal and spatial coordinates, the aura relies on “the unique phenomenon of a distance, however close it may be.”38 For Benjamin, the aura reaffirms the distance between the original/copy binary. Before technology gave rise to mass reproduction, viewing art required pilgrimage to particular locations: catacomb or castle, monastery or mosque. Art objects and their accompanying auras were dependent on in situ rituals.

In this COVID-19 moment of virtual reproduction, art enthusiasts have effectively reclaimed the artistic aura through homage. With canceled flights, suspended visa services, and closed borders, foreign travel has become complicated, if not impossible. At the time of this essay’s writing, the Louvres in Paris and Abu Dhabi had only recently reopened, accessible primarily to local residents. Despite the renown of these institutions, which induces international travel, most foreigners can currently only gain entry virtually as armchair tourists. Early modern loose-leaf broadsheets will not be the souvenirs that today’s couch potatoes acquire from their digital journeys. These virtual pilgrims instead post do-it-yourself mementos as a new quarantine ritual for other stay-at-home wayfarers to view. The coronavirus has prevented physical pilgrimage to these esteemed landmarks, leaving artsy quarantine replicas in its wake. Reenactments with dogs, tuna cans, brooms, and an excess of toilet paper do not challenge Benjamin’s thesis. The aura of the original artwork is never lost or diluted. Instead, the quarantine copies become a new “original” that collapse the distance previously traversed in pilgrimage. In lockdown, semblance becomes a unique mode of self-expression and self-preservation to counteract the shelter-in-place conditions of COVID.

The museum challenge doppelgängers provide accessibility to the inaccessible artworks shuttered in museums, and they visualize publicly our private selves in the strangeness of seclusion. They offer vignettes of domesticity, while always remaining tethered to the hallowed spaces of the imitable collection. More importantly, these museum challenge copies testify to events that extend well beyond the museum. Through their viral presence on social media, they document in first person the coronavirus’s global spread. Virality becomes a double entendre, as the biological contagion of the coronavirus mobilizes the immediate internet dissemination of the tableaux.39 These images are “epoch-making works,” to use Joseph Leo Koerner’s words, that separate life into before COVID and after.40 With their glue-gunned accessories, the museum challenge re-creations depict world history in tableau form to represent bodily life within the picture frame and expose bodily loss outside it. They speak of our collective isolation and isolated collectivity with eyewitness authority. As repositories of past masterworks, these COVID copies document our emulative desires for the future of ourselves and our humanity, which we see now with fresh eyes and masked faces.

Dana E. Katz is Joshua C. Taylor Professor of Art History and Humanities at Reed College. Her research explores representations of religious difference in early modern European art. She is the author of The Jew in the Art of the Italian Renaissance (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008) and The Jewish Ghetto and the Visual Imagination of Early Modern Venice (Cambridge University Press, 2017). Her current book project, “Materials of Islam in Premodern Europe,” studies the material effect of Christian and Muslim encounters.

- For their conversations, questions, and insights, I would like to thank Nicole Archer, Sarah Bavier, Kris Cohen, Mark Jurdjevic, Stephanie Leitch, Kathryn Lofton, Lia Markey, Kevin Myers, Akihiko Miyoshi, Sonia Sabnis, Amy Stewart, Michelle Wang, Tara Ward, and the anonymous readers of my manuscript. Because I emphasize the Renaissance artistic practices of simulation, I concentrated my article on early modern images. However, these COVID copies offer an extraordinary array of images from different time periods and cultures, including, for example, Katsushika Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa (ca. 1830–32), Diego Rivera’s The Flower Carrier (1935), and Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog (Blue) (ca. 1994–2000). Enjoy searching for them online during virtual happy hour with a quarantini in hand! ↩

- Renaissance contracts often insisted that commissions (or portions thereof) be completed in the artist’s own hand, rather than that of a workshop apprentice. On autographic art and the early modern contract, see, for example, Hannelore Glasser, Artists’ Contracts of the Early Renaissance (New York: Garland, 1977); Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 1–28; and Michelle O’Malley, The Business of Art: Contracts and the Commissioning Process in Renaissance Italy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005). On Renaissance individualism, see Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (New York: Modern Library, 1954), esp. part 2. ↩

- Getty (@GettyMuseum), Twitter, March 25, 2020, 9:09 a.m. ↩

- Sarah Waldorf and Annelisa Stephan, “Getty Artworks Recreated with Household Items by Creative Geniuses the World Over,” The Iris (blog), March 30, 2020, https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/getty-artworks-recreated-with-household-items-by-creative-geniuses-the-world-over/. ↩

- Joshua Barajas, “Famous Paintings Come to Life in These Quarantine Works of Art,” Canvas (blog), PBS NewsHour, April 15, 2020. See also “In This Quarantine Art Challenge, Creativity Begins at Home,” PBS NewsHour, April 15, 2020, video, 3:38, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BVXuu1U_p8A#action. The number of quarantine copies submitted to the Getty Museum Challenge continues to grow in summer 2021; however, the phenomenon of the COVID copy was at its peak in 2020. ↩

- Laurence Allard, “Selfie, un genre en soi: Ou pourquoi il ne faut pas prendre les Selfies pour des profile pictures,” MobActu, January 14, 2014; and Mairin Kerr, “The Value of Museum Selfies,” edgital, August 29, 2014. ↩

- Sarah Waldorf and Annelisa Stephan, eds., Off the Walls: Inspired Re-Creations of Iconic Artworks (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2020). ↩

- Waldorf and Stephan, “Getty Artworks Recreated with Household Items.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ellery E. Foutch, “Bringing Students into the Picture: Teaching with Tableaux Vivants,” Art History Pedagogy & Practice 2, no. 2 (2017): 1. ↩

- Donald Preziosi, ed., “The Other: Art History and/as Museology,” in The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 452. ↩

- Allison Hadley, “Covid Classics Goes International,” New Haven Independent, April 1, 2020. ↩

- See u/kento-box, “Sharaku Kabuki Portrait—behind the scenes!,” Reddit, May 17, 2020, 12:17 a.m. ↩

- u/kento-box, “My fiancée says I’m handsome . . . like a Japanese woodblock print. Here’s to the Getty Museum Challenge,” Reddit, May 16, 2020, 10:49 p.m. ↩

- See, for example, Julia Eckel, Jens Ruchatz, and Sabine Wirth, eds., Exploring the Selfie: Historical, Theoretical, and Analytical Approaches to Digital Self-Photograph (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). ↩

- Samsung NX Mini’s “Masterpiece” advertising campaign also features reproductions of self-portraits by Vincent van Gogh and Frida Kahlo. On Dürer and the selfie, see also Jason Farago, “Seeing Our Own Reflection in the Birth of the Self-Portrait,” New York Times, September 25, 2020. ↩

- Hagi Kenaan, “The Selfie and the Face,” in Eckel, Ruchatz, and Wirth, Exploring the Selfie, 113–30. ↩

- See James J. Hodge, C. A. Davis, and John Bresland, “‘Touch’: A Video Essay on the Experience of Always-On Computing,” December 3, 2018, video, 19:50. ↩

- Derek Conrad Murray, “Notes to Self: The Visual Culture of Selfies in the Age of Social Media,” Consumption Markets & Culture 18, no. 6 (2015): 490–516. ↩

- Angela Krewani, “The Selfie as Feedback: Video, Narcissism, and the Closed-Circuit Video Installation,” in Eckel, Ruchatz, and Wirth, Exploring the Selfie, 105. ↩

- On types of distances associated with the copy, see Aaron M. Hyman, “Inventing Painting: Cristóbal de Villalpando, Juan Correa, and New Spain’s Transatlantic Canon,” Art Bulletin 99, no. 2 (June 2017): 102–35. ↩

- Elaine K. Gazda, “Beyond Copying: Artistic Originality and Tradition,” in The Ancient Art of Emulation: Studies in Artistic Originality and Tradition from the Present to Classical Antiquity, ed. Elaine K. Gazda (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002), 6. ↩

- See Ellen Perry, The Aesthetics of Emulation in the Visual Arts of Ancient Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005); and Johannes Siapkas and Lena Sjögren, Displaying the Ideals of Antiquity: The Petrified Gaze (New York: Routledge, 2014). ↩

- See, for example, Stephanie Porras, “Going Viral? Maerten de Vos’s St. Michael the Archangel,” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 66 (2016): 54–78; and Hyman, “Inventing Painting,” 102–35. ↩

- See Maria H. Loh, Titian Remade: Repetition and the Transformation of Early Modern Italian Art (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2007). ↩

- Alexander Nagel, Michelangelo and the Reform of Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 3–5. See also Alexander Nagel, “The Copy and Its Evil Twin: Thirteen Notes on Forgery,” Cabinet 14 (Summer 2004). ↩

- Lisa Pon, Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi: Copying and the Italian Renaissance Print (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 67–136; and Edward H. Wouk, ed., Marcantonio Raimondi, Raphael and the Image Multiplied (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2016). ↩

- Loh, Titian Remade, 33. ↩

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, trans. Gaston du C. de Vere, 2 vols. (London: Everyman’s Library, 1996), 2:78–79; and Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori, ed. Rosanna Bettarini and Paola Barocchi (Florence: Sansoni, 1984), vol. 5:1 (Testo), 4–7. ↩

- On Vasari’s storytelling, see Paul Barolsky, Why Mona Lisa Smiles and Other Tales by Vasari (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 1991); and Pon, Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi, 137–54. ↩

- Joseph Leo Koerner, The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 209. ↩

- See, for example, Peter Parshall, “Imago Contrafacta: Images and Facts in the Northern Renaissance,” Art History 16, no. 4 (December 1993): 554–79; Koerner, Moment of Self-Portraiture, 208–14; Pon, Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi, 141–42; Christopher S. Wood, Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), esp. 164 and 360; Alexander Marr, “Walther Ryff, Plagiarism and Imitation in Sixteenth-Century Germany,” Print Quarterly 31, no. 2 (June 2014): 131–43; Claudia Swan, “Counterfeit Chimeras: Early Modern Theories of the Imagination and the Work of Art,” in Vision and Its Instruments: Art, Science, and Technology in Early Modern Europe, ed. Alina Payne (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2015), 216–37; and Stephanie Leitch, “Dürer’s Rhinoceros Underway: The Epistemology of the Copy in the Early Modern Print,” in The Primacy of the Image in Northern European Art, 1400–1700: Essays in Honor of Larry Silver, ed. Debra Taylor Cashion, Henry Luttikhuizen, and Ashley D. West (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2017), 244–45. ↩

- Daphne Winifred Louise Fielding, Emerald and Nancy: Lady Cunard and Her Daughter (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1968), 56. See also William S. Smith, “Tableaux Vivants Are Giving Us Life during the Pandemic,” Art in America, May 8, 2020. ↩

- Gabriel Tarde, “Monadology and Sociology,” in The Social after Gabriel Tarde: Debates and Assessments, ed. Matei Candea (New York: Routledge, 2010), 61. See also Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 15. ↩

- See Elisha Cohn, “Oscar Wilde’s Ghost: The Play of Imitation,” Victorian Studies 54, no. 3 (Spring 2012), 474–85. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken, 1968), 218. ↩

- Walter Benjamin found a sense of humor necessary for critical and creative deliberations. He writes, “Let me remark, by the way, that there is no better starting point for thought than laughter; speaking more precisely, spasms of the diaphragm generally offer better chances for thought than spasms of the soul.” Benjamin, Understanding Brecht, trans. Anna Bostock (London: Verso, 1998), 101. ↩

- Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 222. ↩

- See Porras, “Going Viral?,” 54–78. ↩

- Koerner, Moment of Self-Portraiture, 35. ↩